Scenes of whirling dancers in a dance hall, a café dansant, or an elegant ballroom have inspired visual artists throughout the ages. This blog has regularly addressed the artist’s portrayal of social dancing. Therefore, before exploring a further collection of late 19th- and 20th-century images, permit me a quick revisit to some stimulating paintings by Jan Sluijters, Vincent van Gogh, Kees van Dongen, and Isaac Israëls.

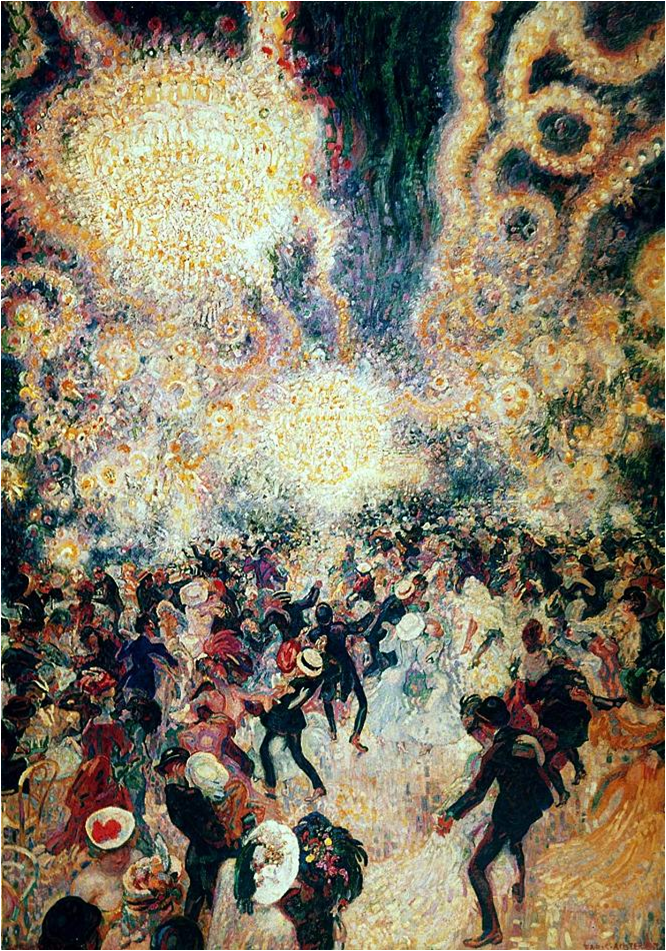

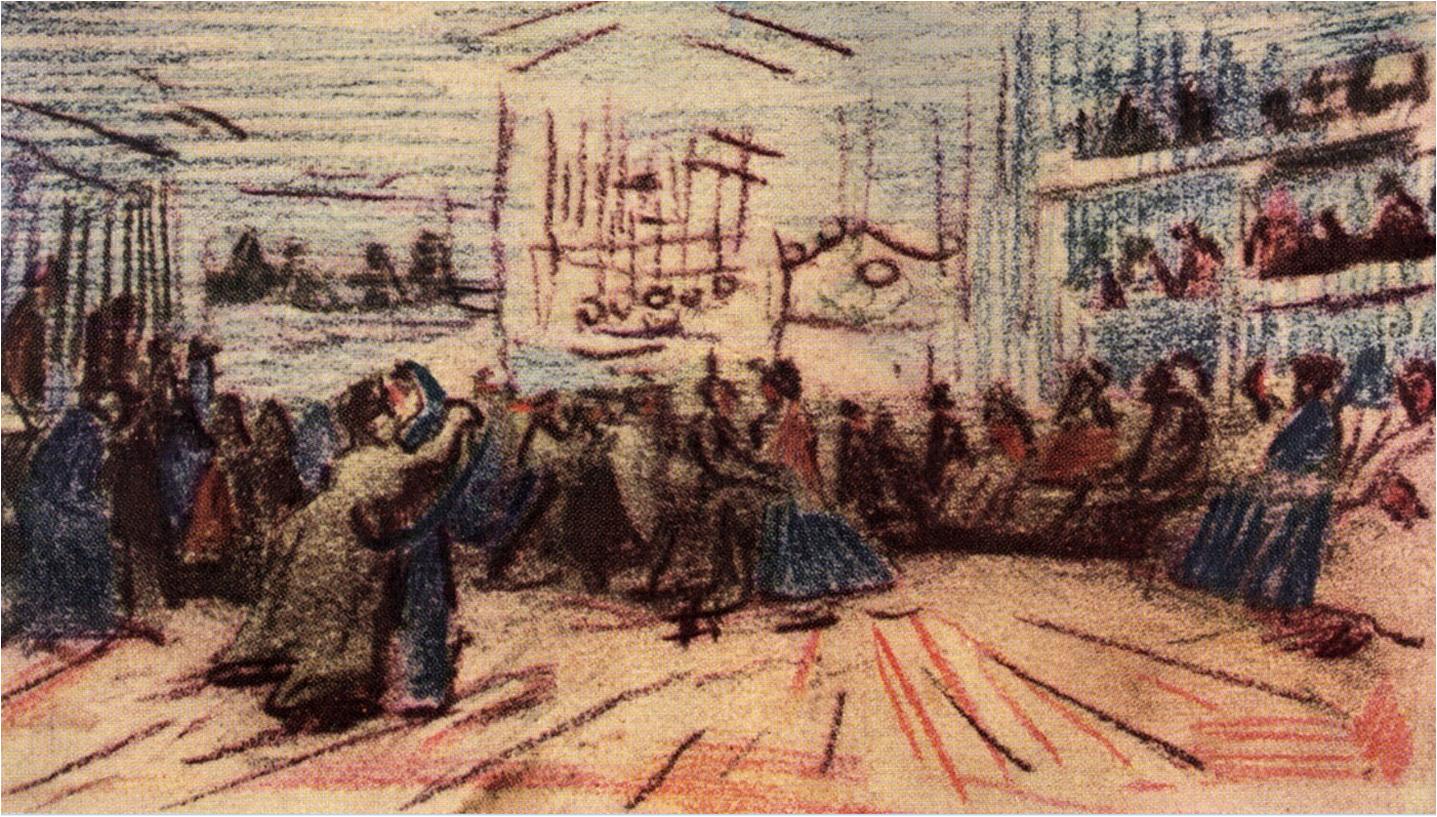

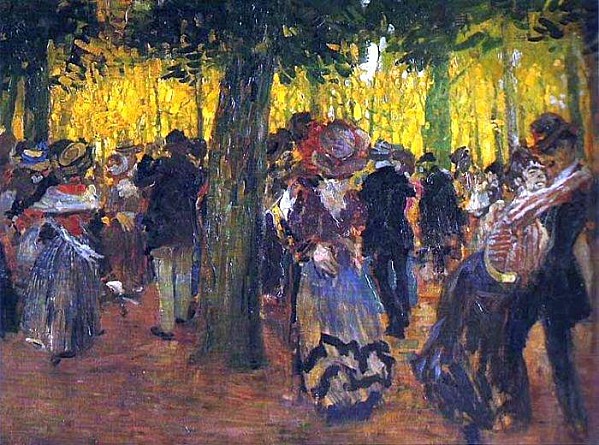

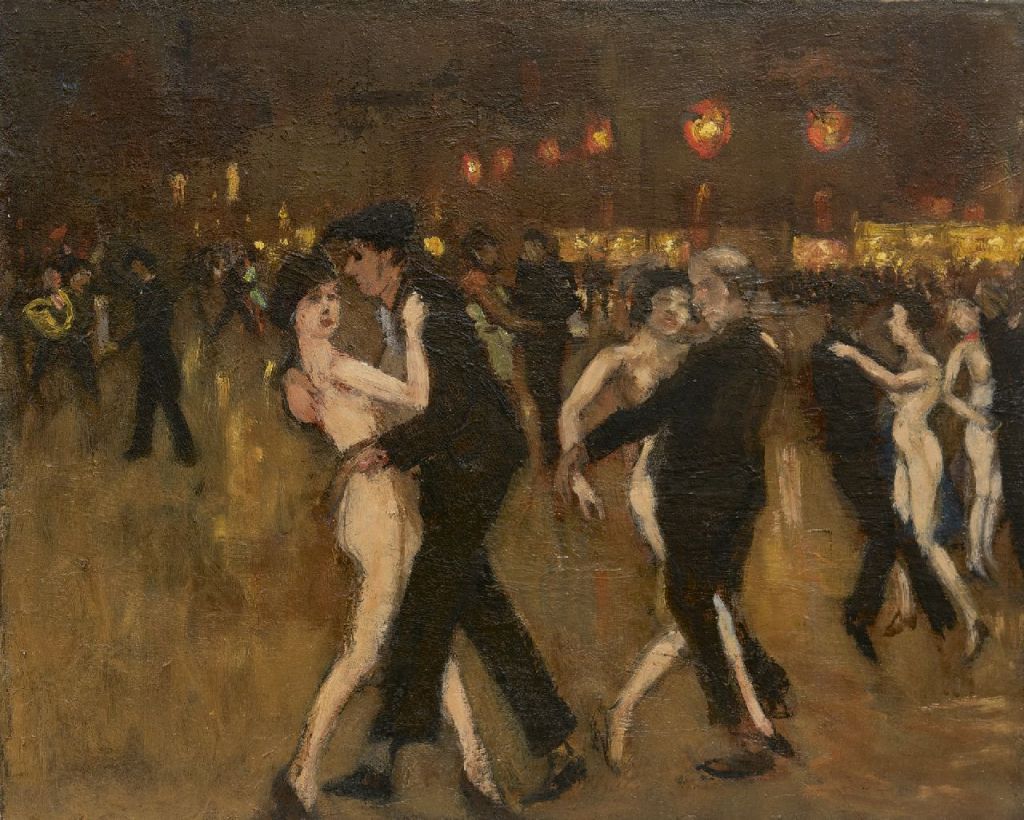

Jan Sluijters’s Bal Tabarin (1907) salutes electric illumination. A vibrant light towers above untold revellers; some couples dance, others drink and dine, and all revel under a banquet of light. In Dance Hall (1885), Vincent van Gogh captures the energy and exuberance of a bustling dance hall. Kees van Dongen was a passionate dancer. His painting captures the effervescent atmosphere of merrymakers at the Moulin de la Galette, while Isaac Israëls’ Dancing at a Fair in the Jordaan (c. 1894) showcases celebratory dancers lit by the innovative invention of electric light. (1)

Electric light also fascinated Henri Braakensiek (1891-1941). The exuberant couples, in the image below, dance rhythmically beneath an aura of light. Braakensiek has accentuated the light rays in white above the three couples on the left. The frieze-like gouache is undated, but based on the contemporary clothing, the women’s hairstyles, and most especially the uninhibited dance movements, the 1920s seems a likely estimate.

The eight pairs are arranged in a horizontal line. The couple on the far left dance forcefully; the man practically shoves his partner off balance. There are also couples dancing intimately. Others, like the portly man and his companion, enjoy a leisurely dance. And there is a vivacious couple dancing a Charleston, and, further along the line, a fervent couple dancing what appears to be a tango. Braakensiek presents a diversity of dance styles, rhythms, and tempos, imparting to each couple their distinct body language and expression; the panel celebrates the popular dances of the era.

The following painting, The Ball, depicting graceful dancing ladies and stylishly attired gentlemen, transports the viewer to a fashionable ballroom. The artist, Marius Bauer (1867-1932), is renowned for his oriental works.(2) Regrettably, his remarkable scenes of everyday life, inspired by The Hague School and French Impressionism, are less well-known; all the more reason to highlight the following evocative painting showing anonymous couples dancing in an elegantly lit chamber. The flowing gowns, along with the couples’ proximity and formal arm placement, suggest that they are dancing a waltz. But have you noticed that various figures are not dancing? A number of people wait calmly on the back bench, but the most obvious non-dancers are the couple resting on the red seating. What are they discussing? Might this artwork, similar to those by Edgar Degas or Jean Béraud, depict wealthy men enjoying themselves in the company of young dancers?

Het Bal (The Ball) – oil on canvas – 30,7 x 43,6 cm – date not given – Simonis & Buunk Kunsthandel, Ede

Bauer’s impressionistic work employs a restricted colour palette. Apart from the black, which is reserved entirely for the men’s attire, he limits himself to subtle shades of sandy brown and beige. Note how delicately the hue of the women’s gowns harmonises with the tones of the floor and walls. The atmosphere is further enhanced by the delicate haze that shrouds the scene. Even the red bench has a misty quality. It is uncanny how this indistinct atmosphere triggers the viewer’s enquiring mind.

Soir de Bal – oil on canvas – 115 x 158 cm. – 1899 – Artnet

The stunning colours, the lively dancing, and the vibrancy of the frolicsome scene immediately catch your attention. The Belgian artist Emile Thysebaert (1873-1963) portrayed everyday labourers in street scenes, in the marketplace, in cafés, and at dance events. Soir de Bal, a dance feast at a local venue, is typical of the artist’s sense of social engagement. There is no escaping the explicit figure of a melancholic mother holding her child at the very front of the canvas. Her young daughter stands quietly at her side. The entire town, from young to old, appears to be present at the local dance. The townsfolk are shown relaxing in the background. Even though Thysebaert’s brushstroke is fuzzy, it is still possible to distinguish guests sitting at a table, playing cards, or standing around holding a drink. A few couples take to the dance floor. The front dancing couple draws the viewer into the festivities. The swirling skirt and lively footwork reveal the swiftness of their dancing. Elegance plays no part in this dance. Rather, eye contact, physical attraction, and enjoyment are the prime qualities that Thysebaert attributes to the lively couple and, for that matter, to all the other couples dancing in this bustling establishment.

The following work, a delightful painting by Johan Michaël Schmidt Crans (1830-1907), highlights the musicians. The instrumentalists are perched on a makeshift platform resting atop several beer barrels.

Kermis te Kalmthout /The Fair at Kalmthout – watercolour on paper – 31 x 46 cm – Simonis & Buunk Kunsthandel, Ede

The artist, Schmidt Crans, was born in Rotterdam. His politically and socially engaged cartoons achieved national recognition. Besides his work as a cartoonist and etcher, Schmidt Crans painted historical and genre pieces. The Fair at Kalmthout is a genre piece. The open window reveals a crowd has gathered in front of a market stall. Other villagers are enjoying the street entertainment. You can spot a black top hat belonging to a travelling performer beneath the poster of ‘The Strong Woman’. And then there is a group of young amorous couples spinning, swaying, and capering happily under the musicians’ improvised bandstand. Even though they are shown from the waist up, the artist clearly indicates that they are moving. The upper body motions of the dancers, the way partners hold each other, and the natural rhythm of the head and torso instantly imply movement.

Is there a figure in Café Dansant by Jacob van Rossum (1881-1963) that makes any attempt to move? Every character – the man seated at the table, the waiter, the woman smoking a cigarette, or the dancing couples – is suspended in time. The figures, positioned as if dancing couples, stand rigidly. They are devoid of spirit. Note how tentatively the two ladies with elaborate hats hold each other. Similarly, the leading couple is restrained, although the man’s lowered gaze allows for various interpretations. Curiously, the artist has painted the two women with their backs turned to the viewer in virtually an identical fashion. Both figures lack locomotion. They show no sign or desire to move; even the pianist is immobile.

Café dansant – oil paint on canvas – 34.2 x 46.6 cm – Simonis & Buunk Kunsthandel, Ede

Dancing, by its very nature, is movement. Van Rossum chooses to avoid any form of action. The silence is intriguing. The narrative becomes all the more intriguing when you notice a pink rose lying conspicuously on the floor. There are no other roses in the painting. Was the flower dropped intentionally? Who dropped the rose? Perhaps the seated man who beholds the smoking lady or the man at the little round table offers part of the answer. Their gaze is undeniably intense. Does this artwork truly have the silence it seems to possess at first sight?

The Moulin Rouge has always been a thrilling inspiration for artists. The most famous is Toulouse Lautrec, but many other artists, including Pablo Picasso and the Dutch artists Isaac Israëls, Marius Bauer, and Vincent van Gogh, have painted the iconic Parisian nightclub. But no artist has painted the dance floor of the Moulin Rouge like Marie Henri Mackenzie (1878-1961). There are no can-can dancers anywhere! Rather, Mackenzie illustrates a bizarre scene where clothed men dance with nude women who wear fashionable high heels. Four women are in the nude. The women, all with bob-cut hairstyles, are very similar in carriage, but the men come from different environments. Judging by his beret, the taller, lean man is a labourer. The following man has a more sophisticated demeanour. The front couple is especially distinctive. The amorous figure hovers intently over his partner, but she, ignoring his advances, directs her attention toward the viewer. All the couples dance in an intimately closed position. Their slender bodies and long legs intertwine suggestively, a situation made all the more obvious by the marked contrast of the men’s dark attire juxtaposed against the women’s fair skin.

Ball with Nudes Moulin Rouge (Naaktbal Moulin Rouge) – oil paint on canvas – 40.3 x 50.5 cm – no date given – Simonis & Buunck Kunsthandel, Ede.

Mackenzie, a student of George Hendrik Breitner, was an impressionist. His utilised a dark palette for his landscapes, harbour, and urban scenes. Characteristically, the colour scheme for Ball with Nudes, Moulin Rouge restricts itself to various shades of brown along with a few comparable tones. The dancing couples in the background are clothed; Mackenzie uses dark tones complemented with patches of subdued blue or pale red. The Moulin Rouge is bustling; many couples dance, and others loiter around the bar. All takes place under suspended electric lights that reflect brightly in the long row of mirrors. It is intriguing how Mackenzie manipulates ‘artificial’ light to create a painting that remains both baffling and atypical.

Frans Huysmans (1885-1954) was a member of the Bergen School, an artistic community led by the French artist Henri Le Fauconnier and the Dutch artist Piet van Wijngaerdt. The Bergen School became the first expressionist art movement in the Netherlands. In 1914 Huysmans painted two versions of the Peasant Dance (Boerendans). One was called The Waltz, and a slightly smaller work was named The Polka. Huysmans paints, as is characteristic of the Bergen School, in sharp, angular forms and utilises a strong contrast of light and dark, powerful colours, and bold, broad brushstrokes. (3)

Peasant Dance ‘The Polka’/ Kermis in the Rustende Jager – 1914 – no measurements given – Museum Singer, Laren

Huysmans’ application of electric light is both innovative and effective. The café Rustende Jager is bathed in two light sources — a gentle glow around the bar and, more significantly, a single lamp hanging in the very centre of the upper frame. This striking lamp illuminates the foreground of the artwork, lighting up the ragged faces and undecipherable expressions of the partygoers.

The café is crowded. Some people embrace, others drink, and the central figures beneath the large electric lamp dance. The dance space is confined, allowing limited movement variation. The guests can do little more than move rhythmically from side to side, shuffle from one foot to the other, and occasionally perform a leisurely turn. The title The Polka is therefore perplexing. A polka is an exceptionally lively dance, rich in hops, spins, and advancing steps. It requires ample space.

Let’s Dance celebrates the joy of dancing. With the passage of time, the ballroom, dance hall, and café dansant give way to modernity. In the latter half of the 20th century, Dutch artists lost interest in social dance themes. Possibly, photography, video, or current technological advancements have superseded the visual artist in this particular area.

(1) The block of paintings at the top of the post:

The large painting : Jan Sluijters – Bal Tabarin – 202.5 x 142.5 cm – 1907 – Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam.

Top right: Vincent van Gogh – Dance Hall – chalk on paper – 9.2 x 16.3 cm – 1885 – Van Gogh Museum Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

Centre right: Kees van Dongen – Bal au Moulin de la Galette – 72.5 x 100 cm – 1904-5 – private collection – Artnet

Below right: Isaac Israels – Dancing at a fair in the Jordaan – oil on canvas – 90 x 100 cm – c.1894 – private collection – RKD, Netherlands Institute for Art History

(2) For more information about Marius Bauer please read my post https://artanddance.art.blog/2021/07/15/marius-bauer-artist-inspired-by-the-exotic/

(3) Frans Huysmans painted two great dance scenes. For more information on Dance Hall De Rustende Jager (The Waltz) tap the following link: https://artanddance.art.blog/2022/01/28/dancing-cheek-to-cheek/