Piet Mondrian’s distinctive art images have integrated into everyday life. His explicit composition of lines, shapes, and colours is applied everywhere. You merely need to Google the term Mondrian to discover mugs, T-shirts, coasters, sneakers, big shoppers, cuff links, and clothing inspired by and reproduced in the unmistakable Mondrian style.

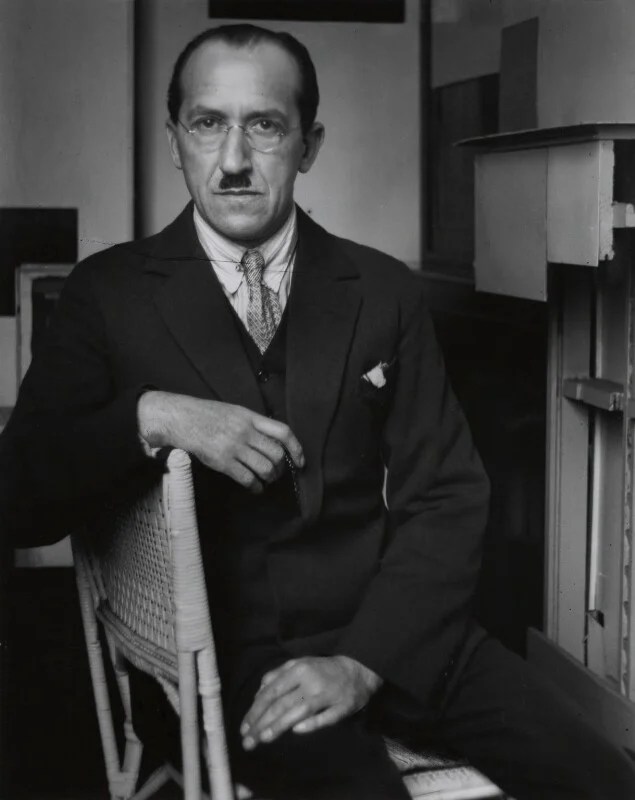

Neither merchandise nor marketing, however, entered Mondrian’s mind. He was a creator, an innovator, and an idealist profoundly influenced by the study of Theosophy. Mondrian, who modified his name from the Dutch Mondriaan to the more international Mondrian, is best known for his abstract grid paintings using the primary colours, red, yellow, and blue. His well-known works are neither narrative nor figurative. His abstract works fused colour, line, and space to form a unified rhythmical whole. Contemporary photographs give the impression that the artist was a serious, conservative man. True in part, but Mondrian had a convivial side, being an ardent jazz lover and an avid dancer enthusiast.

As a younger man, Mondrian frequented the local dance halls. Mondrian considered dancing an exceedingly significant activity. He was neither agile nor especially graceful. Rather, he moved in a particularly striking fashion. Friends and acquaintances relate that his poise was uncommonly upright and that he slanted his head upwards while vivaciously executing stylized, staccato and highly characteristic movements. In the artist’s village of Laren where Mondrian resided during the Great War, he soon earned the nickname, ‘Dancing Madonna’. His friend, the architect J.J.P. Oud, a leading member of De Stijl, describes that:

Although he always followed the beat of the music he seemed to interpolate a rhythm of his own. He was away in a dream …… creating the impression of an artistic, almost abstract, dancing figure.

J.J.P. Oud

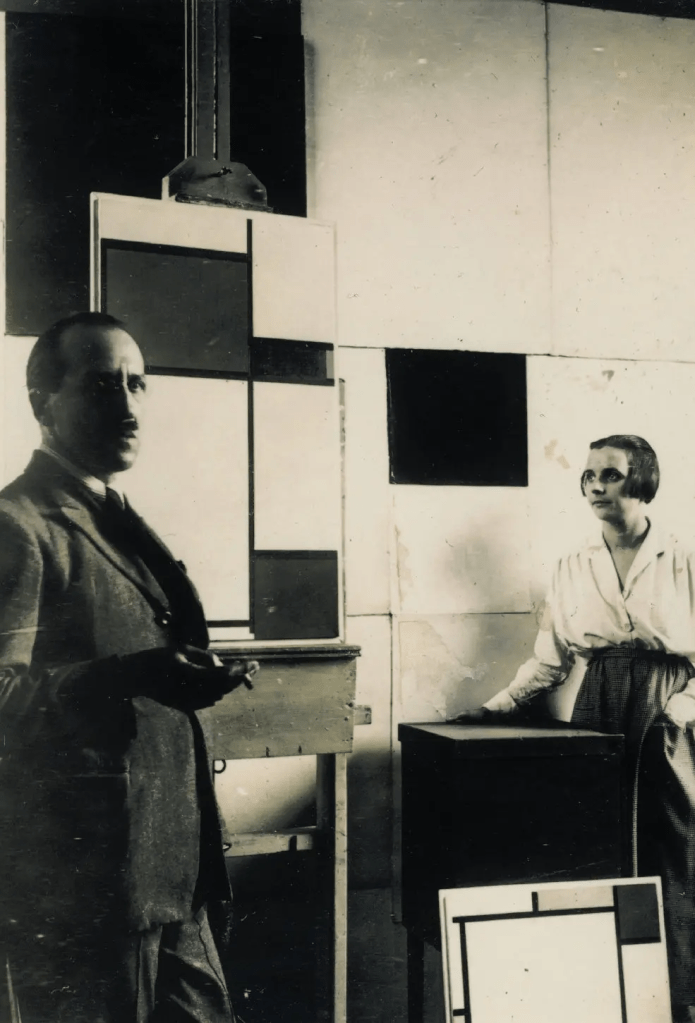

Nelly van Doesburg, pianist, dancer, artist, and wife of Theo van Doesburg, confirms that Mondrian was a great devotee of social dancing and that he took foxtrot and tango lessons. He totally discarded the waltz; the continual turning motion was utterly incompatible with his intense belief in the horizontal and the vertical. Nelly van Doesburg continues to explain that ‘whatever music was being played, he carried out his steps in such a personal stylized fashion that the results were frequently awkward and rarely satisfactory to his partners’.

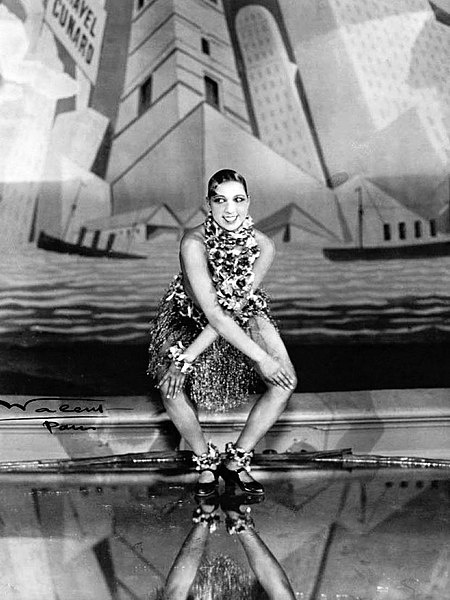

Mondrian also held strong views on art, music, and dance. As a founding member of De Stijl Mondrian wrote a series of articles expressing his radical opinions, denouncing the antiquated traditions and conventions of the arts. He championed the innovative music of his friend, the avant-garde composer Jakob van Domselaer, became highly interested in the intonarumori compositions by Luigi Russolo, and above all, he became a jazz enthusiast. Theatrical dance did not escape his attention; Mondrian disparaged the expressionistic dancers, Isadora Duncan and Gertrud Leistikov, proclaiming them as individualists and traditionalists. On the other hand, the performances of Les Ballets Suédois met his approval, as did the Diaghilev Ballets Russes, though he disapproved of Picasso’s design for Parade. But most especially, Mondrian delighted in Josephine Baker, who, as the leading dancer of the Ballet-Negrès, was acclaimed for her exhilarating Charleston. Mondrian had several photographs of Josephine Baker performing her riveting dance on his studio wall.

During Mondrian’s New York period, the artist Lee Krasner, wife of fellow artist Jackson Pollack regularly accompanied the now-older artist to Barney Johnson’s Café Society in Greenwich Village to enjoy the latest jazz music. They were often accompanied by Alexander Calder, Fernand Léger, Peggy Guggenheim, and other prominent figures. Lee relates that although she is a fairly good dancer, when dancing with the artist she found that ‘the complexity of Mondrian’s rhythm was not simple in any sense’.

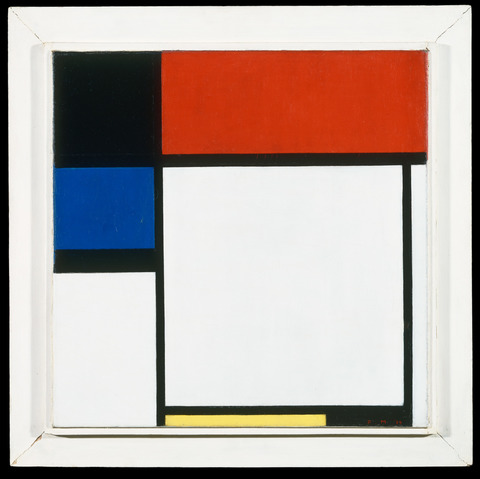

To return to social dancing. Mondrian regarded the fashionable charleston, with its contrasting sharp, angular, and concise movements, as the modern dance, a manifestation of modern life. He found the shimmy equally appealing, writing a friend that ‘for me (it is) the most enjoyable dance there is’. Not surprisingly, Mondrian was captivated by one of the most popular social dances, the foxtrot. The foxtrot was originally danced to a 4/4 ragtime rhythm. The basic foxtrot figure is a simple walking step moving forward or backward, followed by a sideways movement danced to a slow-slow-quick-quick rhythm. Each figure uses three counts of the 4/4 measure, which means that the basic foxtrot figure does not consistently start on the first count of the measure. Rather, the dancer constantly shifts accents in the course of a four-measure phrase. This diverging rhythmical approach would have appealed to Mondrian in his continual exploration of duality; he juxtaposes the vertical and horizontal, primary colours and non-colours and, in the case of the foxtrot, acknowledges the disparity between the dancer’s initial movement and the strong musical accents. During an interview that took place in the early 1920s, Mondrian expressed the idea of naming one of his works Fox Trot. That initial thought was abandoned, but a decade later, he named two distinct works, Fox Trot B and Fox Trot A.

Mondrian, as with most artists who painted abstract paintings, named his works Composition, or some other neutral title, often adding a letter or a colour designation. Paintings with a title such as foxtrot, waltz, or shimmy, invariably feature figures illustrating the actual dance. Mondrian was unique in naming two non-figurative, non-narrative works with an associative title as Foxtrot.

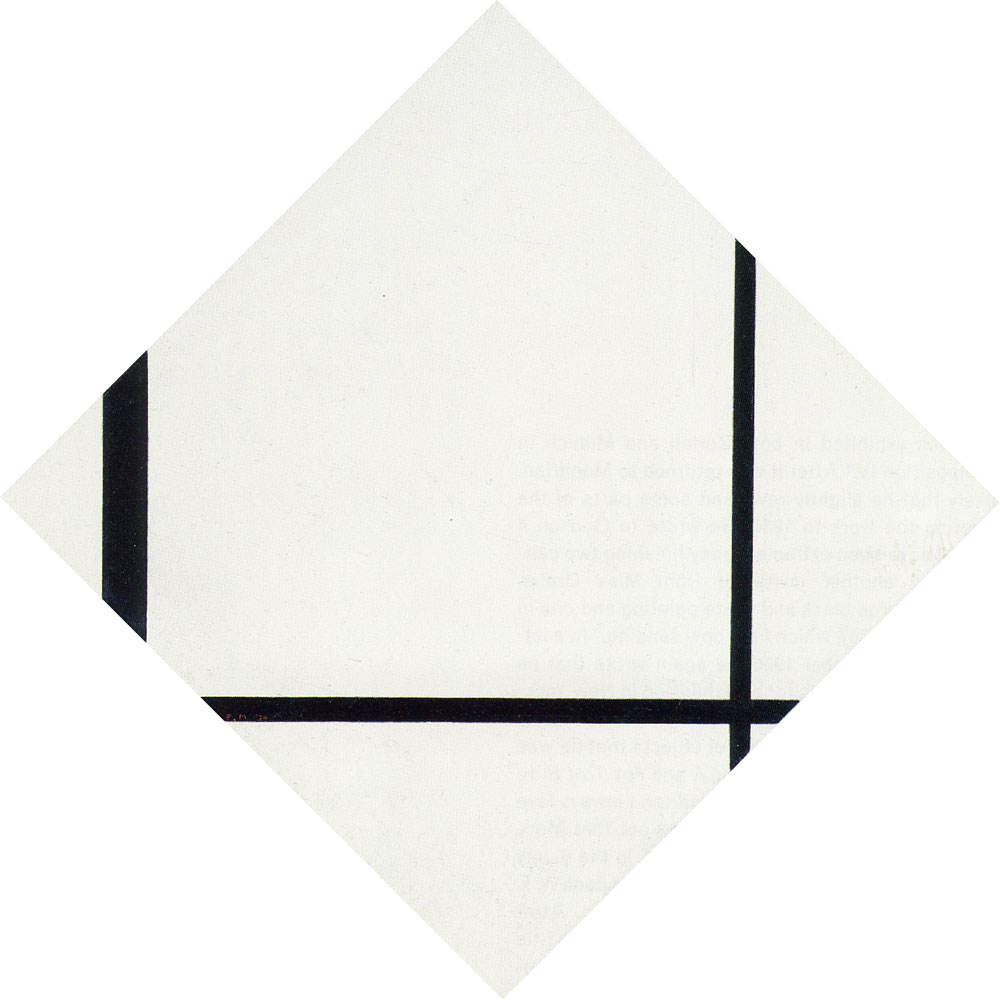

But how do you relate Fox Trot B, with Black, Red, Blue, and Yellow, to the popular dance, the foxtrot? Essentially, the foxtrot moves on a horizontal and vertical line. This perpendicular floor pattern corresponds with Mondrian’s staunch adherence to his aesthetic principles, Neo-plasticism, where the artist restricts himself to only using horizontal and vertical lines. You could possibly argue that the specific composition of the various shapes is suggestive of a slow-slow-quick-quick rhythm. Fox Trot A: Lozenge with Three Lines is more enigmatic. Mondrian has rotated the square canvas at a 45-degree angle. The intangible white space is enriched with three lines, each of a different length and width. None of the lines have a beginning or an end. Each line forms an infinite horizontal or vertical path; the viewer can sense the boundless continuity. But these aspects have, to my understanding, no straightforward link to any dance. And I can imagine you wondering: What have Fox Trot A and Fox Trot B in common? And why did Mondrian name these two specific abstract works Foxtrot?

110 cm diagonal, sides 78.2 x 78.2 cm

Oil on canvas – 1930

Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven (original title – Composition no. IV)

A footnote in a very thought-provoking article discussing Mondrian’s fascination with jazz music by Harry Cooper (1) sheds some light. He points out that these two paintings were originally titled Composition no. III and Composition no. IV and that, in all probability, Mondrian renamed the paintings in preparation for a show in New York, reasoning that a descriptive title like Fox Trot would draw additional public attention. Perhaps an anti-climax, but the mere fact that Mondrian chose Foxtrot and not any other dance, definitely confirms his unquestionable attraction to the rhythm, the movements, and the physicality of the dance he loved dancing.

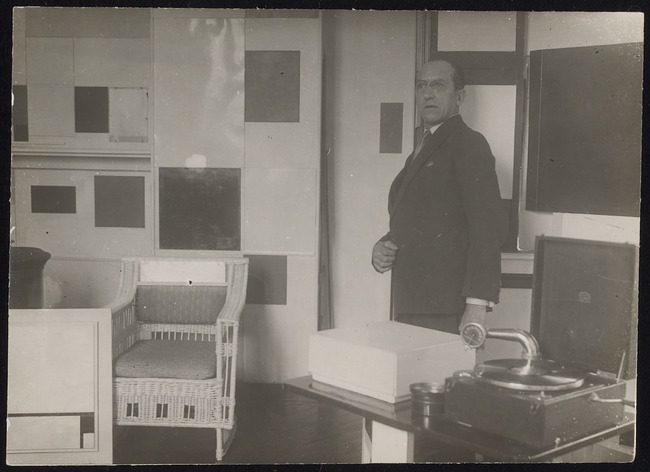

The two snapshots pictured offer a personal insight into Mondrian’s Paris and New York Studios. When Alexander Calder visited Mondrian’s Paris Studio in 1930, he ‘walked into a painting’. The room was bright, and the furniture was painted white or black; Mondrian had even painted the Victrola red to harmoniously fit in with the surroundings. Years later (1945), Lee Krasner visited Mondrian’s New York Studio to discover that besides the Victrola, Mondrian had collected ‘a stack of Blue Note jazz records to which he danced barefoot in his studio’. Mondrian was a dancer in heart and soul. His paintings, as we will see in the following post, were ingrained with jazz and dance elements; the onlooker encounters a harmonious, yet dynamic and rhythmical sensation. Nelly van Doesburg splendidly conveys how absolutely essential dance was to Mondrian when she reveals that:

‘his friends would be forgiven all other faults if only they had wives or companions young, attractive and willing enough to accompany him to the dance floor’

Nelly van Doesburg

(1) – Music and Modern Art – edited by James Leggio – Popular Models: Fox-Trot and Jazz Band in Mondrian’s Abstraction – Harry Cooper – footnote 52, page 197 – Routledge Taylor & Francis Group ISBN 978-1-138-99429-4 (pbk), first issued in paperback 2015

Photographs of Mondrian in the his studio:-

- Mondrian in his Paris Studio, 1929 – photographer unknown – Netherlands Institute of Art History

- Mondrian in New York Studio, early 1943 – photographer Fritz Glarner – Netherlands Institute of Art History