Theo van Doesburg (1883-1931), the driving force behind De Stijl, was a man of immense talent. He was not only an artist but also a writer, a poet, a typographer, a theorist, an architect, a designer, a performance artist, a teacher, and a photographer. Van Doesburg was exceedingly interested in all artistic disciplines and participated energetically in social, technological, and philosophical discussions and activities. As foreman of De Stijl, he was an ardent promoter, advocating their revolutionary ideology, editing the magazine De Stijl and delivering unofficial lectures to members of the Bauhaus (1). As a poet, writer, and performer, he launched a series of avant-garde performances, introducing Dada throughout the Netherlands.

Inspired by Cezanne and the Cubists, van Doesburg explored the possibility of modifying realistic or stylistic figures into geometric forms. His exploration was intensified by Kandinsky’s remarkable writings on inner expression. Van Doesburg sought pure art, investigating the expressive qualities of colour, line, and form. The preliminary drawings of Dancers (1916), a work evolved from an image of the Hindu god Krishna, provide an insight into his ‘step-by-step towards abstraction-method’ (2) that Van Doesburg applied to uncover his absolute essence of art.

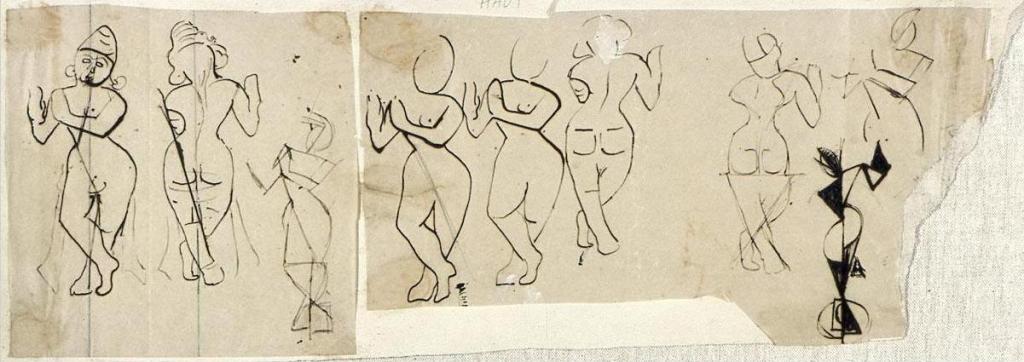

The above two images present an insight into the preliminary process. The first, a small pencil sketch, presents a front and back view of a moving figure. The headpiece and long earrings, together with the contrapposto deportment, indicate the image has an oriental origin. The figure, having crossed the right leg over the left, leans effortlessly to the side, the hip and thigh protruding. Counterbalancing this marked curve, the arms extend to the right, reminiscent of Krishna, who is frequently portrayed holding a flute. Van Doesburg further highlights the dancer’s movement range by accenting the figure’s diagonal axis. The vaguer figure, propped in the right-hand corner, has retained the bulging thigh but yielded some of the curves; the torso and shoulders are now formed by straight lines. Additionally, the face and the head have lost their oriental appearance. The five figures in the longer sketch have retained their counterbalance stance, lost their specific facial features, and are further stylized. They are still recognizable as human figures. That is not the case for the singular figure in the lower right-hand corner. This back view image of the dancer is formed by black and white geometric planes on an absolutely vertical axis. Especially noteworthy is that van Doesburg has substituted a round base for the previously crossed-over feet; the dancer appears to be tolling. This sketch, as we will see, closely resembles the figures in the painting Dancers (3).

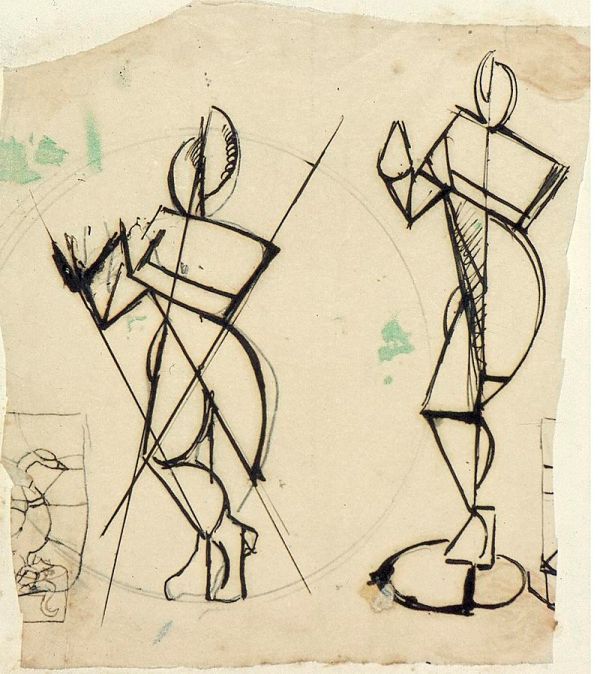

Pursuing his exploratory path, van Doesburg transforms the left figure — still recognizable with the bulging hip and crossed-over feet — into a longer, stylized configuration of geometrical shapes. The bulging hip has become a protruding semi-circle; the shoulders are now a rectangle, and the hands, feet, and legs have transformed into triangles of various sizes and shapes. The original feet have been replaced by what appears to be a two-part circular disc. At the apex, two half-oval shapes — one placed slightly higher than the other — supersede the head. This front-view figure, together with the back-view figure, will further evolve to become the two components of the groundbreaking diptych Dancers (1916).

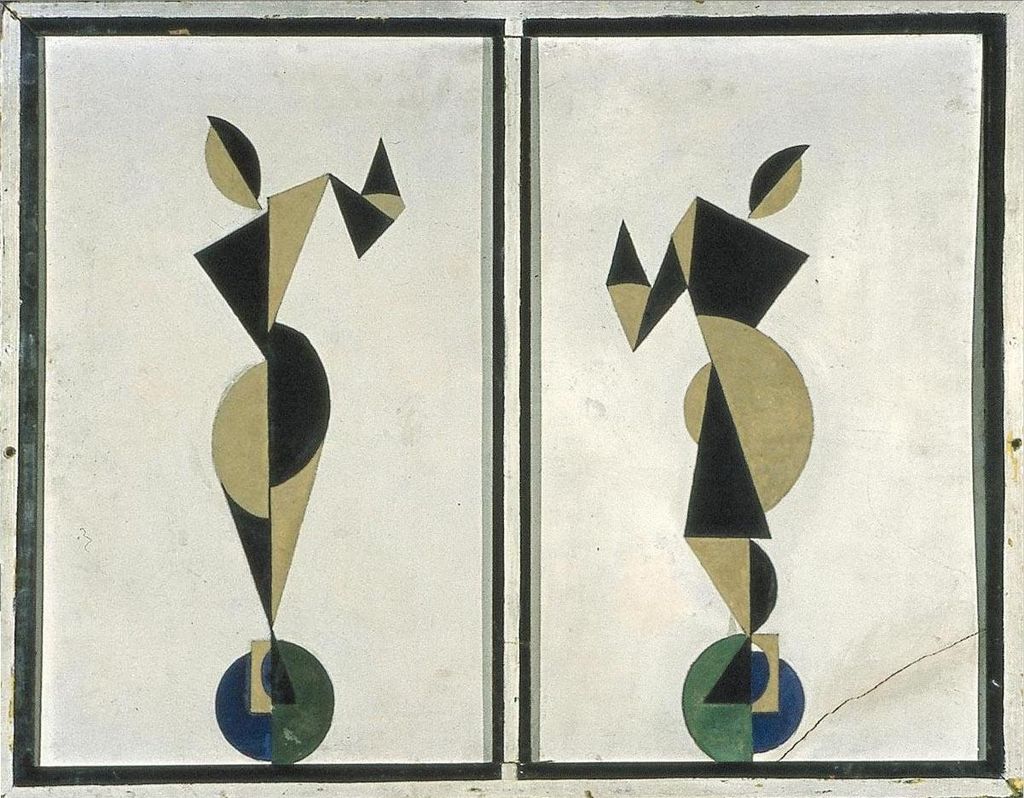

The dancing figures have ‘step-by-step’ been stylized into an abstracted form. At this stage in van Doesburg’s exploration, it was not uncommon that the final representation still vaguely recalled the original subject. The gentle curves of the dancers and the subtle placement of the ‘heads’ are indebted to the earliest dancing figures, but where the Krishna image appears to delicately sway or turn, these dancers hover above a disunited circular base. Moreover, the base is only partially connected to the underground, giving the impression that the dancers are balancing on a rotating sphere.

Perusing the dancers, it soon becomes apparent that even though they are composed of corresponding shapes and colours, the dancer’s proportions and contours are, in fact, quite different. The back-view figure emerges from a bi-coloured triangular shape, moving into semi-circles of opposing colours. The semi-circles, though asymmetrical, are of complementary size, unlike the front-view figure which has clearly retained the extended curve of the bulging hip from the original Krishna figure. The torso and upper limbs are similar in colour but deviate in orientation and shape.

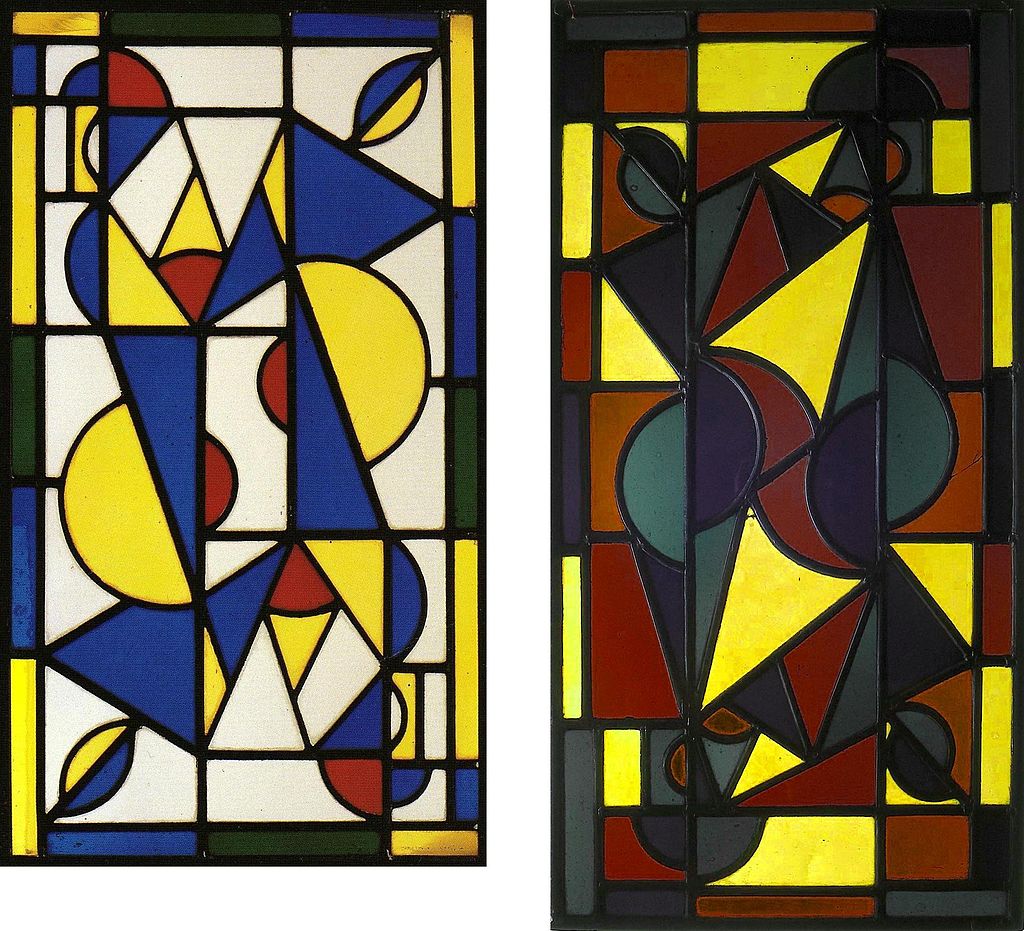

Up to now, I have only discussed van Doesburg’s drawings and paintings. Painting, however, was by no means van Doesburg’s primary goal. He, like the other members of De Stijl, was an ardent believer in art as an integral part of society. New-age art must be objective, functional, and accessible to all. This universality would be achieved through abstraction: lines, planes, and colours. To establish these utopian ideals in practice, De Stijl involved their ideology to architecture, furniture design, interior design, and applied art. The following two works, stained-glass windows, fit entirely within these aims.

Theo van Doesburg- Dance I and Dance II – stained glass windows (Dance 1 47 x27cm & Dance II 50.5 x 25.5 cm) Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands

The path to abstraction continues onward. In Dance 1 van Doesburg employs the front-view figure twice. On the right-hand side, the familiar dancing figure is posed upright; on the left is an identical figure, inverted 180 degrees. The right and left halves have exactly the same shapes, colours, and lines and would be mirrored if the figures were not flipped. Notice how the brightly coloured dancers come to the fore, lighting up between white stained-glass panels. The primary colours of Dance I make way for the more secondary colours in Dance II. Van Doesburg applies the same structural composition as in Dance 1 but now using the back-view of the dancer. The original ochre planes embellishing Dancers are substituted for dark green forms, and the original black shapes have become a deep blue. Additionally, the background and foreground fuse together. The relatively neutral background in Dancers has been substituted with eye-catching yellow tones and demure brownish red hues; background and foreground fuse together. Van Doesburg, characteristic of De Stijl, has abandoned the differentiation between negative and positive space.

Dance I and Dance II have travelled a great distance from the original Krishna figure. Colour, line, and shape are now manifest without the dancers yielding any of their dynamism. On the contrary, Dance I is spirited, and the juxtaposition of shapes and colours lends an animated expressiveness to a work that was created at a time when The Great War raged around the world. The unambiguous symmetry in Dance II, to my mind, deeply expresses a vivid sense of harmony and balance. Abstraction, in the case of van Doesburg, is a means to heightened expressionism.

In a letter to his friend, the writer and poet Antony Kok, van Doesburg, after discussing the multiple creative possibilities music offers, writes

I feel dance to be the most dynamic expression of life and therefore the most important theme for pure visual art.

Letter Van Doesburg tot Anthony Kok, 14th Juli 1917 (my translation) (4)

1) Theo van Doesburg did not actually teach at the Bauhaus. He taught and lectured privately in Weimar, meeting and inspiring many Bauhaus teachers and students.

2)Titles of the above artworks are not always consistent. I have chosen to use the titles of the artworks as listed in Theo van Doesburg oeuvre catalogus – Centraal Museum, Utrecht & Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo 2000 — editor Els Hoek — ISBN 906868 255 5

3) For the term ‘step-by-step towards abstraction-method’ I wish to thank the Centraal Museum, Utrecht and Kröller Müller Museum, Otterloo. The term is used and explained in their information leaflet prepared for their joint exhibition on Theo van Doesburg. (2000)

4)The quote (my translation) is to be found in Theo van Doesburg 1883-1931— Evert van Straaten — published by Staatuitgeverij, ‘s-Gravenhage — 1983 — ISBN 90 12 04216 X — page 77 (in Dutch)

5) Theo van Doesburg’s design for Dance II has survived the test of time. It is housed at the Kröller Müller Museum, Otterlo.