An esteemed portraitist, painter of world landscapes and market scenes, man of the world and court painter, the Flemish artist Lucas van Valckenborch (c.1535 – 1597), depicted peasant dance and court dance in a number of his paintings. During his early training van Valckenborch studied in Mechelen, a centre specializing in world landscapes. He and his contemporaries, Pieter Bruegel the Elder and Hans Bol, lived in turbulent times. The iconoclastic fury that raged through The Low Countries in 1566, together with the religious persecution of the period, compelled Lucas van Valckenborch to flee, travelling first to Liège and later to Aachen. In 1579, he was appointed court painter to the Archduke Matthias of Austria, governor of the Spanish Netherlands in Brussels, who commissioned various portraits, landscapes and nine allegories depicting the seasons. Illustrations of the seasons illustrating the labours of the months, traditionally located in the calendar section of a book of hours, found their way to the canvases of Pieter Bruegel the Elder and other artists of The Low Countries. Lucas van Valckenborch painted an extensive series depicting the seasons; five are in the collection of the Kunsthistorische Museum in Vienna.

Autumn Landscape (September), a large work, can be classified as a world landscape. A high ridge with hard-working peasants leads into a magnificent panorama set around a Romanesque castle. The viewer is granted a bird’s eye view of the countryside extending as far as one can see. The peasants, celebrating the successful harvest, play games, feast, glide across the water, visit the market, and enjoy a theatrical performance. And they dance! Jolly rustic folks are enjoying a frolicsome get-together, kicking their legs effortlessly in the air as they dash spontaneously in a circular formation. The contrast between the rigid, stationary bourgeois and the irresistible cheerfulness of the labourers could not be greater.

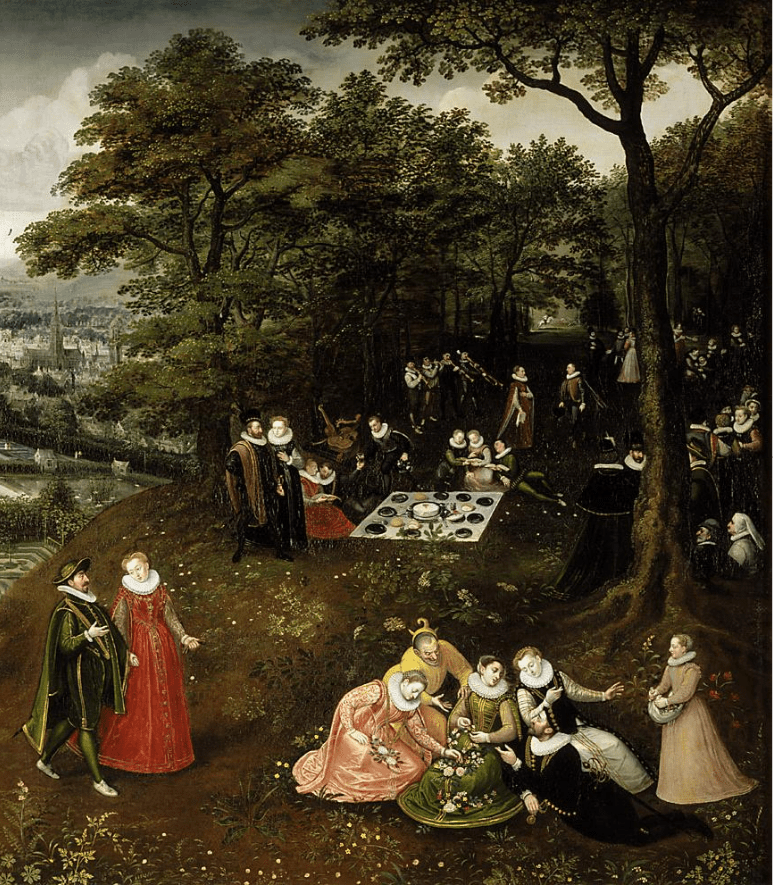

Spring Landscape (May) divides the scene into two distinct sections. On the elevated hill top, aristocratic ladies and gentlemen are enjoying a sophisticated picnic. Moving down the hillside, an amazingly detailed vista comes into view: an enclosed garden, diverse towers, a maze, and an imaginative panorama of Brussels and faraway surroundings. Van Valckenborch also bisects the canvas, thus contrasting light and dark. The scenic view, the epitome of wealth and grandeur, is completely exposed to daylight, though subdued by vast menacing clouds. The aristocracy parties on a firm, dark, earthy surface. The front figures catch the light, but the picnic table, the musicians, the dancers and other guests are shaded by a canopy of trees.

Amongst the elegantly attired nobles participating in courtly pursuits is one dancing couple, promenading, not to the rhythm of a rustic bagpipe, but to the accompaniment of the finest woodwind instruments. The dancing couple, like the musicians and the other courtiers, is inconspicuously placed under the shady trees. The dancer’s cultivated carriage and refined bearing suggest that these nobles were trained in etiquette and courtly dance. Not long before Spring Landscape was painted, the Italian dancing master Fabrizio Caroso wrote one of the earliest dance manuals, Il Ballarino (1581). Italian dance masters, as a matter of interest, were known for their travels, teaching dance and etiquette at European courts. Intriguingly, the dancing couple in van Valckenborch’s painting resembles, both in presence and appearance, an illustration deriving from Caroso’s influential manual. (See centre image below)

Unsuspectingly, halfway down the right-hand side, a peasant couple enters the scene. The couple conceal themselves behind the mighty tree. They seem awestruck, gazing incessantly at the affluent lords and ladies. These uninvited guests evoke the iconic Bruegel dancers. It is puzzling as to why van Valckenborch placed these peasant folk in a distinctly opulent court setting. Curious, moreover, is the wise fool beckoning the young woman in the front group; she barely notices him, enchanted as she is by the affectionate man reclining on the grass. Fools, of course, were flamboyant personages in many a Renaissance court, but this fool has a hideous disposition, disturbing yellow attire and peculiar projections on his hood. No doubt this representation of spring, divulging a sky laden with ominous clouds, inquisitive peasants and a cautionary fool, opens the possibility for various interpretations.

Centre: Il Ballarino – 1581 – Fabritio Caroso

Right: Pieter van der Heyden – The Peasant Wedding Dance – after Pieter Bruegel the Elder – after 1570 – Metropolitan Museum of Arts, New York – detail

The village scene of revellers drinking, rioting, and dancing, in front of a local tavern, as shown in Landscape with a Rural Festival, brings the festive scenes by Pieter Bruegel the Elder to mind; the children playing with a hobby-horse, the bagpipe player, and the dancing couples, are all typical of the time. We recognize the Bruegel iconic dance types; the couple that face each other, the woman turning under her partner’s uplifted arm, couples dancing at arm’s length and couples dancing back to back. Van Valckenborch painted a lively group of dancers swirling and turning unflaggingly, to the animated rhythm of the music. These dancers, to a greater extent than Bruegel’s characteristic couples, revolve and twist the torso, hips, and back arduously. They dance enthusiastically. Van Valckenborch must have been intrigued by the diversity and virtuosity of movement. He has captured these rustic dancers and their movements realistically.

There are two versions of this painting. One in The Hermitage (Leningrad) and a slightly smaller version in the Prado (Madrid). I have chosen the Prado version because the image is brighter allowing a clearer view of the dancers and the dancing.

The rural dance festival is a mere segment of a larger world landscape setting. The lively celebrations take place on a rocky plateau behind which a landscape, with mountains, villages, valleys, and boundless skies evolve. It is possible to divide the painting into three overlapping and yet separate sections. On the left, the rustic folk are occupied with their coarse activities. Directly opposite, an extensive landscape unfolds. In the centre, peasants and the well-to-do town folk are in conversation. Contemporary paintings and engravings have identified these urbanely attired gentlemen. The man playing the bagpipes represents the artist himself. George Hoefnagel, an artist of considerable renown, is shown talking to a farmer and Abraham Ortelius, the cartographer recognized as the creator of the modern atlas, is directly behind the man (unidentified) staring at the viewer.

In the following painting known as A Village Kermesse, a church and mountainous landscape beyond, the dancers essentially steal the show. The spacious landscape, the distant villages, the church, the procession, and those imposing oaks are entrancing, but the group of revellers, amorous couples, and fun-loving peasants are positively riveting. Young and old caper over the hilltop; the exuberance of the dancers is irresistible. Notice how hastily the three couples gallivant down the ridge. The men practically dart, pulling their partner actively forwards. And what about the middle-aged couple that frankly overshadows all the other figures? The rustic’s open overcoat reveals his rotund figure, exposing his unsightly attire and codpiece. Nevertheless, he and his equally unattractive partner are vivacious dancers, still perfectly capable of prancing to and fro and kicking their legs into the air. To my mind, they resemble Bruegel’s famous Wedding Dance couple, with the understanding that this couple, by comparison, is crude and squalid. The remaining dance couple echoes the back-to-back dancing formation found in Albrecht Dürer’s famous engraving, Peasant Couple Dancing. Later, the back to back design was to become one of the memorable dance figures in Bruegel the Elder‘s work. Van Valckenborch continues the tradition and adds his own innovation; the dancers span farther apart, plunge forcefully into a widespread stance counterbalancing their partner’s sweeping movement. The seated man, evidently enjoying the action, raises his arm in encouragement.

This travelogue of paintings by Lucas van Valckenborch would not be complete without the following selection of roundels; each has a diameter of twenty-five to thirty centimetres. These delicate miniature paintings, representing a peasant wedding or a village kermesse, embody unmistakable characteristics of Flemish peasant painting as handed down by the legendary artist, Pieter Bruegel the Elder.

The four roundels present various aspects of Flemish peasant life. Common to all is the lofty tree which divides the foreground from the environs. All the action takes place in the vicinity of that imposing tree. The background, be it an infinite landscape or a village tavern, is painted with extraordinary precision. If you take a moment to expand each image, you cannot but be overwhelmed by van Valckenborch’s unwavering detail. Whether a musician, children at play, an inebriated man stretched out on the ground, an uninhibited woman relieving herself or couples enjoying each other’s company, each figure is realistically portrayed.

Peasant wedding. Wedding Dance in the open air – 1574 – 30 x 29.5 cm

Statens Museum for Kunst, National Gallery of Denmark

A River Landscape with the Blind leading the Blind, a kermesse in a village beyond – Christie’s

Dance-wise, the first roundel Peasants making merry is similar to A Village Kermesse, a church and mountainous landscape beyond. Various figures galop down the hill and, in typical Bruegel style, other couples prance and whirl enthusiastically. The artist has added a new element; two youngsters dance gleefully with their elders. In both Peasant Wedding and Wooded Landscape, villagers have formed a large circle, dancing hand in hand, to the lively accompaniment of the bagpipe player. The dance in the last roundel is less obvious; there is a circle dance taking place in a field not far from the church. There is, furthermore, a religious procession entering the church which could indicate this is a saint’s holy day. However, the towering tree, the large farmhouse and the bridge draw the viewer’s attention to the front figures; the blind leading the blind. Their fate is inevitable. This theme, derived from the book of Matthew, appeared in the work of Hieronymus Bosch and later developed by Pieter Bruegel the Elder. In combining a biblical theme with village ribaldry, Lucas van Valckenborch, as his master, Pieter van Bruegel, subtlety invites the viewer to contemplate the secular and the sacred.