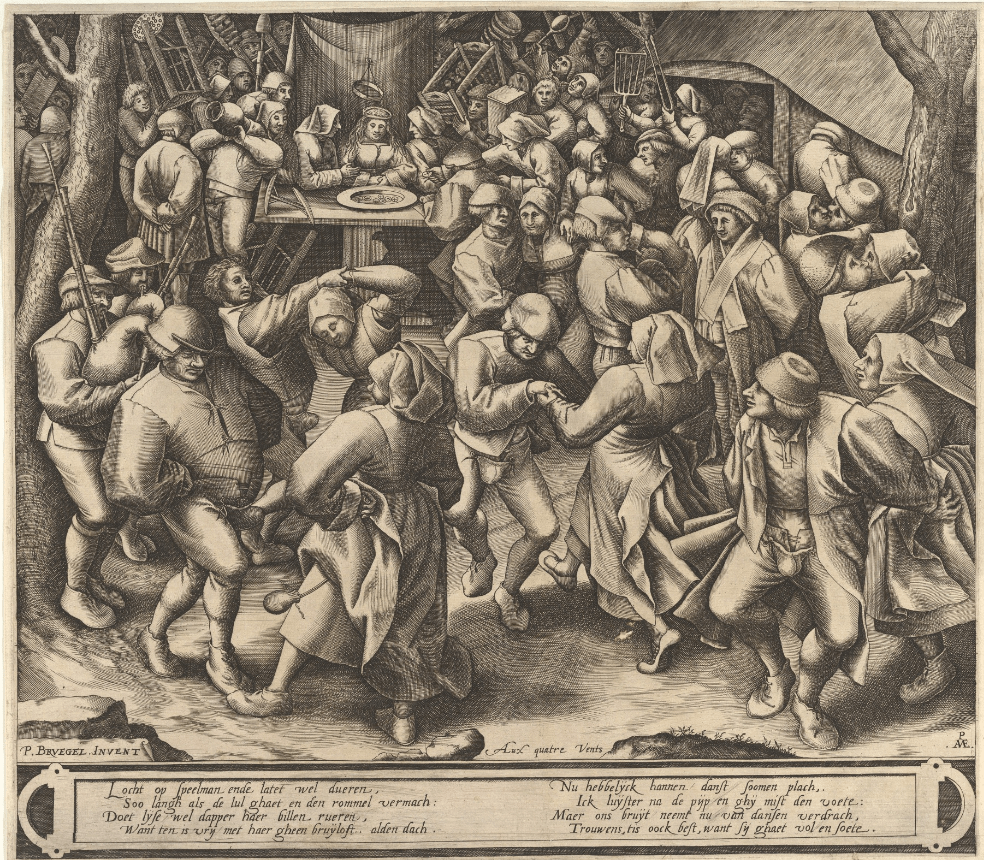

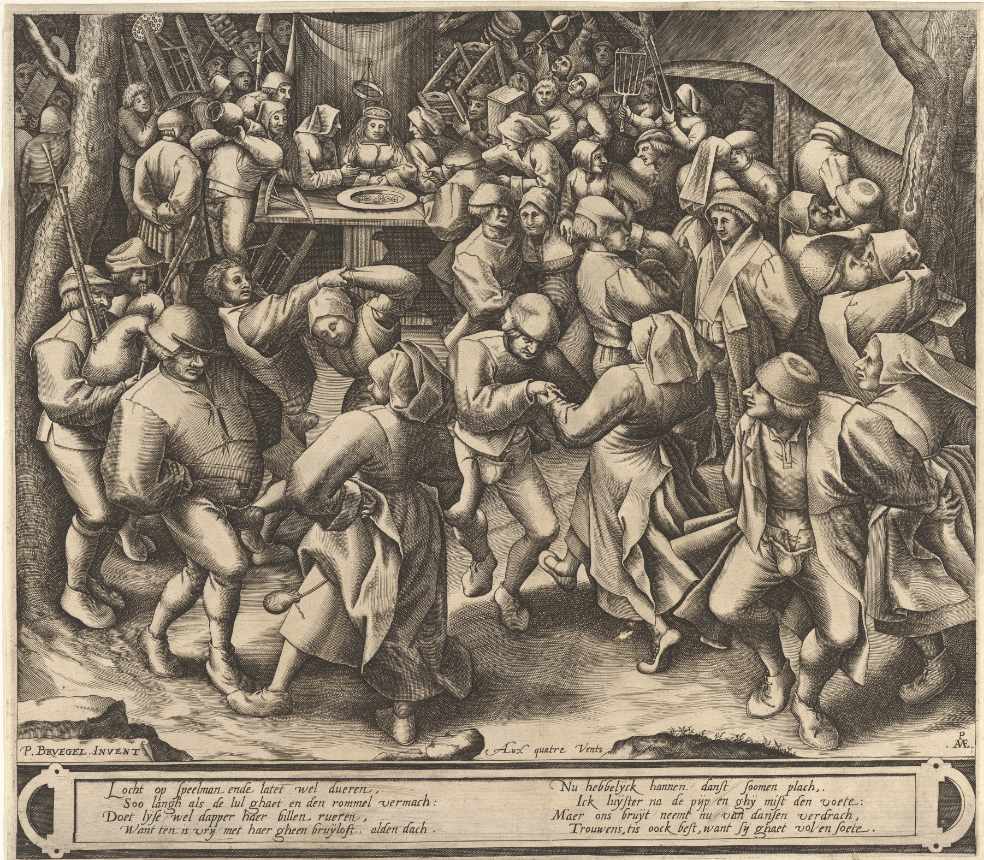

Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s original work, upon which The Peasant Wedding Dance is inspired, has been lost. Fortunately, Pieter van der Heyden engraved a work, presumed to be a copy of Bruegel’s painting, sometime after 1570. The setting of The Peasant Wedding Dance is, in part, comparable to The Wedding Dance (1566) where four dancing couples command the foreground. Three couples derive directly from the Detroit painting, whilst the fourth couple, though reminiscent of the figures in the 1566 painting, is essentially different in appearance and character. The kissing couples, the hugging couples, the observing outsider, the discreetly urinating man, the imbibed men and the bagpipers players, well known from The Wedding Dance, are all present. But contrary to The Wedding Dance, the bride in The Peasant Wedding Dance does not dance. She is seated at a table well behind the dancers, in front of a cloth of honour decorated with a rudimentary crown. Hovering over her are two matrons (her mother and mother-in-law?) eagerly helping her to count the coins placed on the platter that rests on the table. On either side of her, guests enter the scene, bringing useful household gifts. I can see stools, a broom, jars, a ladle and a cot. The text under the engraving, not added by Bruegel himself, explains the situation. The last line clarifies that the bride is full and sweet, meaning to say, pregnant.

Maer ons bruijt neemt nu van dansen verdrach, Trouwens tis oock best, want sij ghaet vol en soete Our bride has given up dancing, Which, by the way, is for the best, because she's full and sweet.

The foremost dancers are the largest figures in both the painting and the engraving; the entire front layer is virtually dominated by the dancers. All the other activities take place behind them, frequently by less prominent and appreciably smaller figures. The leading dancer’s movements, clothing, demeanour, temperament, and facial expression are clearly perceptible. Each couple is so spaced that there is relatively little overlapping, which contrasts strongly with the clusters of miscellaneous figures intermingling in the background.

In 16th century Flemish art, the bride is traditionally seated at a table. In The Wedding Dance, contrary to general custom, the bride is a vivacious dancer. She, together with her somewhat older partner, leads rustic couples in a reel. The bridal table, habitually the centre of attention, is not particularly obvious. In fact, the viewer has to take a moment to explore the work to discover the makeshift table snugly tucked away in the background. In The Peasant Wedding Dance, the bride has reverted to her traditional position; sedately seated at her table. Having eliminated the dancing bride and her companions, Bruegel draws the bride and her bridal table to the fore. She and her rowdy guests are now unmistakably present; over the head of the large dancing peasant woman, over the uplifted arm of the revolving woman, a straight line leads directly towards the bride. The elevated view, further underscores the sight line.

It is evident that the figures and the format of the engraving derive from Bruegel’s 1566 painting. Naturally, there are some slight differences. The sturdy man and the equally hardy woman, dancing on the left, are more earthbound in the engraving. She, instead of jovially trotting, now has both feet firmly planted on the ground. The centre figures, though still very playful, appear to be a little older and the third couple, where the woman turns under the man’s arm, has gained prominence. The painting shows the slightly smaller and subordinate couple being overshadowed by the gleefully robust, front couple. The engraving, in contrast, presents them as one of the four significant dancing couples.

Right: The Peasant Wedding Dance – Pieter Bruegel the Elder (designer) – Pieter van der Heyden (engraver) – 42.3 cm x 37.5 cm – engraving – after 1570 – The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The most stunning deviation – dance-wise – is the whimsical couples dancing in the lower right corner. Dissimilar as they appear, the couples basically have a comparable design. In both instances, the man has turned his back towards his partner and the woman reaches forward in a diagonal line. The man, especially, is a comical fellow, somewhat snoopy and just slightly dubious. In both the painting and the engraving, these characters are flanked by a kissing couple(s) and a silent, observing visitor.

The couple depicted in the engraving, the more elderly couple, are a cruder, decrepit, version of the figures featured in the 1566 painting. The man, a rugged personality, is far less sprightly than his younger counterpart. He is earthbound, ponderous and manoeuvres heavily on his awkwardly bent knees and unshapely shoes. Yet, despite his cumbersome carriage, he nonetheless manages to grasp his partner’s behind. This peasant woman, weathered by the daily grind of rural life, is more than eager to join in with the festivities. Inasmuch as we can ascertain, taking into account that the figure has been cropped, the flow of her headscarf and the line of her body would seem to indicate that she is moving swiftly. Just for the record, in the engraving, the bagpiper players have moved to the opposite side of the image; they now lean against a sturdy old oak, reminiscent of the musician in Albrecht Dürer’s engraving, The Bagpiper (1514).

The Peasant Wedding Dance came to be one of the most popular Flemish genre images of the late 16th and early 17th centuries. It was copied or imitated more than a hundred times and became known by a variety of different names including, The Wedding Dance in the Open Air and The Outdoors Wedding Dance. No fewer than thirty-one copies have been attributed to Pieter Brueghel the Younger. Bruegel’s younger son, Jan Brueghel the Elder, made a modest number of paintings inspired by his father’s work, aside from developing his own specific wedding dance compositions. Other imitations were produced by artists working in Pieter Brueghel’s workshop, his followers and independent Flemish artists. Martin van Cleve, contemporary to Bruegel the Elder, produced an entire series based on the wedding theme, including quite a few outside wedding celebration scenes.

Though the multiple copies differ in artistic quality and craftsmanship, they retain many common features. In every painting, the rough elderly couple dances in a corner, the three familiar dancing couples move rhythmically to the sound of the bagpipers, numerous couples are hugging, and the bride, her hair falling over her shoulders, sits at her table. Occasionally, the villagers present household gifts, but more often than not, the bride is decidedly more interested in the coins being placed on the platter.

Each individual painting, though painted by a variety of artists for a large and varied market, is unique. The similarities and dissimilarities are boundless; there are quite a few examples where the image has been mirrored. The following images present an opportunity to compare just a few of the paintings. You may enjoy perusing the facial expressions, the bagpipe players, the observing outsider, the setting (especially the number and positioning of the oaks) and clothing in general. And from a painterly point of view, there are intriguing deviations in colour, brushstroke, texture, and perspective.

Pieter Brueghel the Younger or Jan Brueghel the Elder – The Wedding Dance – 18.3 x 21.8 cm – early 17th c. – Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence

Pieter Brueghel the Younger – Peasant Wedding Dance – Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento

Generally speaking, we can establish that the four dancing couples, in all the imitations and reproductions, are near identical copies of the figures presented in Pieter van der Heyden’s engraving, The Peasant Wedding Dance. This work, in turn, was replicated from a painting by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, now lost. Furthermore, many of the additional figures, including the bride and her companions, correspond closely to those in the engraving. The background, in contrast, constantly changes. Depending on the size of the panel or perhaps on the instructions of the patron, trees, foliage, cottages, and the like materialized, changed in appearance or vanished completely.

To conclude, I must point out that Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s sons were mere toddlers when their father perished. 16th century artist and art historian Karel van Mander informs us that the brothers were taught the art of painting by their grandmother Mayken Verhulst. Did she teach them to reproduce their father’s work? It is known that, during his lifetime, many of Bruegel’s paintings had already left Antwerp to become part of prestigious collections throughout Europe. How did the brothers, and most particularly Pieter, having no access to their father’s Wedding Dance produce such faithful reproductions? Recent research by Dr. Christina Currie, offers fascinating insights; to be continued…