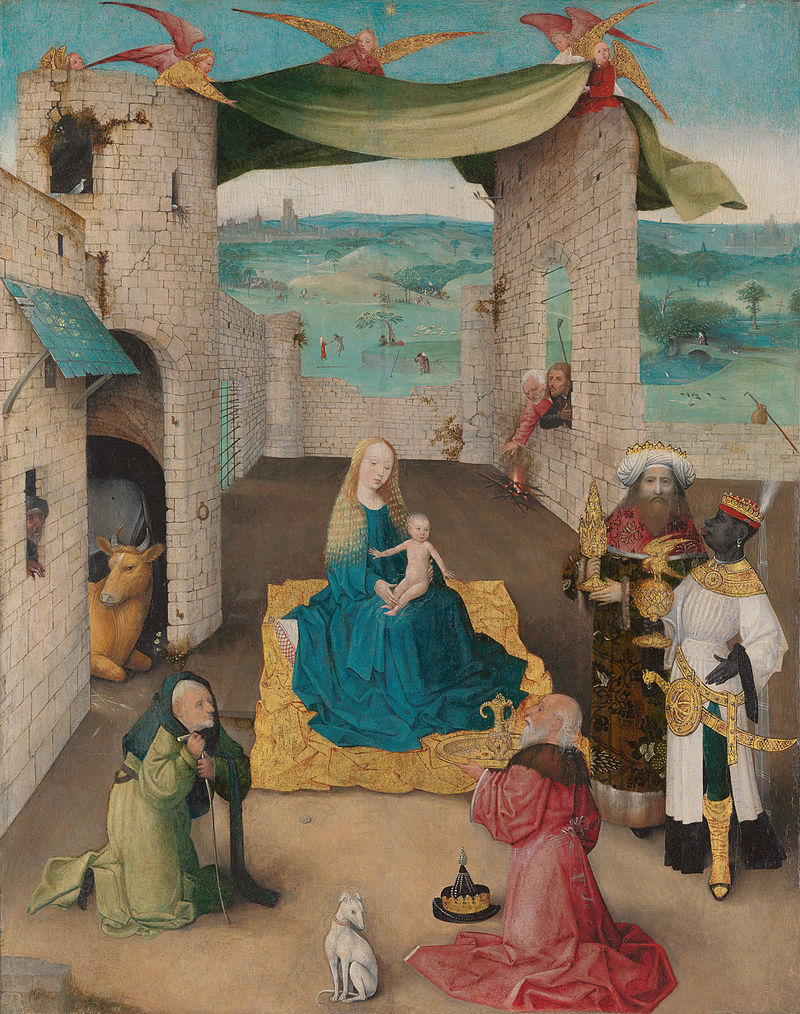

Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s peasant paintings are emblematic. The Peasant Dance (1568), The Wedding Dance (c. 1566) and The Peasant Wedding (c. 1566-69) are arguably the best known peasant paintings ever painted. Bruegel’s paintings, however, famous as they are, were not the first examples of peasant dancing in The Low Countries. Peasants, be it dancing, feasting, or working, regularly decorated the margins of illuminated manuscripts. And then there are the paintings by Hieronymous Bosch (1450-1515), the Dutch artist whose nightmarish scenes, full of eerie creatures, send chills down one’s spine. Three of his works feature peasants dancing to the accompaniment of a bagpipe player. In both versions of The Adoration of the Magi, the dancing peasants are little more than miniature figures dancing in the vast landscape. Somewhat larger, though still small, is the dancing couple on the outer panels of The Haywain. While Bosch and his predecessors allocated a subordinate role to the peasant, Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528), the Nuremberg master artist dramatically placed the peasant in the spotlight. His engravings of peasants and most especially for this post, Peasant Couple Dancing (1514), usher in a hitherto understated subject; rural life and rustic festivities. Inspired by German artists as Dürer and Sebald Beham, a new art genre, village fairs and festivities, arrived in The Low Countries early in the 1550s.

Right: Albrecht Dürer – Peasant Couple – engraving, 11.8 x 7.5 cm – 1514 – Metropolitan Museum of Art

Sebald Beham and his contemporaries exhibited the peasant as a rowdy, ill-mannered, drunken fellow. Scatology was never avoided; the images were intended to be satirical. Early Flemish artists followed the German example, but where Sebald Beham designed his woodcut, The Village Fair (Large Kermis), as an elongated horizontal plane, Flemish artists staged a similar village scene that unfolded into an endless landscape.

Pieter van der Borcht (c. 1535 -1608), born in Mechelen, composed one of the earliest Flemish images of a village fair. This etching, made in 1553, still owes much to older German works; the tavern, the excessive drinking, the fighting, and not to forget the vomiting. Yet despite the various borrowings, the differences are obvious. The outstretched frontal view, used by Sebald Beham, has made way for long, oblique lines, giving the illusion of remarkable depth; the eye of the onlooker is drawn into the background. There, layer by layer, the ambience is divulged. The festival, being a religious holiday, is celebrated with a procession. Rows of peasants can be seen promenading towards the church. And farther back you can see a village, beyond which more charming Flemish houses and woodland surroundings. These are but a handful of details when compared to the activities taking place at the front of the image. There is, to mention just a few, unrestrained drinking, merrymaking, wooing, acrobats standing on each other’s shoulder, a butcher selling his wares, and a canoe sailing on the river. However, the long-legged dancers, moving in the immediate foreground, steal the show. Not only are these dancers larger than any of the other figures, they are also depicted in greater detail. The three rustic couples hop, skip, and jump, kicking their legs in the air, all the time, swirling and rotating underneath their uplifted arms. This is a lively and decidedly energetic dance; possibly encouraged by the bagpipe player and, no doubt, just a little help from the barrel of ale conveniently placed behind them.

In another version of a village fair, Pieter van der Borcht, still indebted to Sebald Beham’s work, depicts a fair abounding in lowbrow behaviour. The foreground is dominated by hideous fighting, boisterous villagers drinking, a child defecating, a woman urinating near a tree, a drunken man collapsed on the ground and a circle of rowdy dancers. Van der Borcht, as in his other images of village fairs, allows the onlooker an extensive vista. Village fairs were initially a church celebration, which over time, much to the dissatisfaction of church leaders and town officials developed into profane festivities. Van der Borcht’s print makes this very clear; the church just as the religious procession has been delegated to a less prominent position – the back of the image. The exuberantly vivacious peasants, on the contrary, coarse and crude as they are, command the forefront.

Instead of depicting couples dancing, as customary to the German images, Van der Borcht places his dancers in a circle; the men and women alternate. A 1549 etching, often attributed to Van der Borcht, shows peasants dancing in a circle, but these are not in the foreground nor are they exceedingly rowdy. The peasants shown in the image below, on the other hand, are a rough bunch. They push and shove each other as they rapidly swerve and wheel around in a circle. And that wretched woman, stuck between two spirited men, cannot but jump in the air, to avoid being squeezed. The woman facing her with the grotesque grimace yells, as she and the tarnished men continue their brisk dance. All the while, the musicians and the inebriated revellers encourage the hustle and bustle gleefully. More villagers participate in the merriment; just behind the circle, various country couples enjoy a sprightly dance.

According to late 16th century art historian Karel van Mander, the townsman Bruegel the Elder gatecrashed festivals and weddings dressed as a peasant. Whether this account is true or not, Bruegel, a contemporary to Pieter van der Borcht, definitely took a more optimistic approach to peasants and rural life than his predecessors. For instance, the satire seen in earlier German and Flemish prints is less pronounced, as is the blatant exhibition of scatology. Pieter Breugel the Elder, before painting his famous peasant paintings, designed a number of prints illustrating village fairs, including Kermis of St. George and The Hoboken Kermis.

In both these early works, as was the practice at the time, Bruegel gives the viewer a bird’s eye perspective of the entire village square, extending the vista to the outskirts of the village and even, as in Kermis of St George, to another town in the remote distance. From a high vantage point, the onlooker is invited to explore groups of people, all small figures, occupied in a potpourri of activities. Some peasants dance, others drink, children play with a hobbyhorse and a few ruffians are tumbling. Moving beyond, the figures become even smaller. Minuscule figures gather round the church; some are watching a play performed on a makeshift stage, and others gather round, remember these are the St. George celebrations, a dragon on wheels. And in the far distance, near the windmill, archers are shooting strangely shaped birds. This print, meticulously illustrated, is packed with so many unexpected activities; an absolute adventure to explore.

According to an ancient legend, St George rescued a young princess, slaying the dragon, to whom she was about to be offered. It is, therefore, no coincidence that, in this image, a celebration of the holy day dedicated to St. George, Bruegel allocates the sword dance in the most prominent position, the centre of the print. You will have noticed (expand the illustration) that directly behind the dancers a young girl is being escorted towards the dragon; fortunately, St George comes to the rescue. The dancers themselves are most likely a group of travelling performers; not uncommon at the time. The sword dancers all wear the same clothing, have the same hats, wear similar footwear, and have rings of bells fastened around their calves. Four pairs of dancers raise their swords well above their heads, enabling the other dancers to run under the ‘bridge’. These same dancers also turn to face each other. In all probability they stoop, turn, and duck under the arches forming elaborately complicated and decorative patterns. There is no accompanying musician in the vicinity – I wonder if these performers fabricated their own musical accompaniment? Perhaps the sound of clashing swords and tinkling bells was more than sufficient. There are, however, two bagpipe players standing just in front of the tavern door in the outer right corner. There, a group of lively couples dance exuberantly.

In composition, apart from a less far-reaching background, The Hoboken Kermis, contains many of the same elements as Kermis of St George. The viewer, once again, from a high vantage point, looks down on a village square where peasants are dancing, drinking, playing, walking in a religious procession or, in the back right-hand section, watching a performance or possibly listening to a quack.

The round dance immediately catches your eye; the men and women, their hands linked, stand alternately. The arms are stretched out sideways. The women come across as sturdy holding, as it were, the circle in balance to support the men as they perform more complicated footwork. Breugel’s dancers are nimble, swift, and fun-loving; inviting other couples to participate. Behind the bagpiper players you can see other couples running to join in; the back couple, so it seems to me, moves very similarly to the well-known running couple that Bruegel would eventually paint, as sizeable figures, in The Peasant Dance, a few years later.

Bruegel the Elder – The Peasant Dance – c. 1568 – Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna – detail of dancers

Van der Borcht and Bruegel the Elder established the theme of peasant festivals in the Low Countries. Van der Borcht designed peasant prints before Bruegel, and it is more than likely that he inspired Bruegel. Both artists were well acquainted, working for the same publisher. Bruegel, nonetheless, is identified, more than any other, as the artist of peasant life. During Bruegel’s lifetime, many of his peers, including Peter Baltens, Hans Bol, and Martin van Cleve mastered the art of peasant festivals. Bruegel’s work, very much in demand in his own time, gained immeasurable popularity through the reproductions, imitations and recreations of his work by his son Pieter Brueghel the Younger, his workshop and his followers. Images of village scenes and festivities remained fashionable for more than a century.