The name, Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, evokes visions of antiquity; ladies in Grecian gowns reclining on marble benches overlooking an unfathomable ocean or Romans at leisure enjoying their opulent villas, swimming in luxurious baths surrounded by exquisite flowers and wondrous architecture. Alma-Tadema explores the ancient world, taking his inspiration from Egypt, Greece and Rome. Dance is rarely a principal theme. Dance and dancers, however, intermittently appear and, at times, in the most unexpected way. Common to all dance images, in whatever guise, is that they flow directly from antiquity.

The sphere and setting of Between Hope and Fear are perplexing; an older man conversing with a younger, apparently reserved, woman. Possibly a father speaking to his daughter, or, equally possible, if the wall painting is any clue, a more suggestive ambience of a prostitute and her client. Apart from the satyrs, the red background painting reveals a feminine musician and at least two maenads, followers of Dionysus. Maenads, known from Greek antiquity or their Roman counterpart Bacchantes, followers of Bacchus, danced compulsively in tumultuous frenzy. As they danced barbarous rituals, they tossed their flowing hair wildly, flaunted torches (thyrsi), played flutes and pounded their hand drums (tympana).

With his extensive knowledge of antiquity, Alma-Tadema, freely echoed images that enhanced vases, wall paintings, tomb paintings and artefacts. In Between Hope and Fear, ecstatic maenads, inspired by vase drawings, follow a parade of salacious satyrs. Alma-Tadema models the frieze adorning the Roman villa in The Soldier of Marathon, on a funeral dance, found on the inside of an ancient tomb. The fresco, discovered in Ruvo di Puglia, Italy, (1833), shows Peucetian women dancing.

Alma-Tadema choreographed every aspect of his work, including the design of the frames. Each frame harmonized artistically with the setting, sphere, and the mood, of the painting. Entrance of the Theatre, probes into elements of Roman social order, inducing parallels with Victorian society. Dance may not appear on the canvas, but a little dancing cymbal player balances, like a Russian gopak (or hopak) dancer, on the upper section of the frame.

- The Soldier of Marathon – oil on canvas – 39.5 x 56.5 cm – 1865 – private collection

- Above: Tomb of the Dancers – Ruvo di Puglia – Naples National Archaeological Museum

- Centre: Entrance of the Theatre (Entrance to a Roman Theatre) – oil on canvas – 67.4 x 96 cm – 1866 – Fries Museum, Leeuwarden (Netherlands)

- Below: Entrance of the Theatre – 1866 – Fries Museum Leeuwarden – Upper section of frame with dancing cymbal player

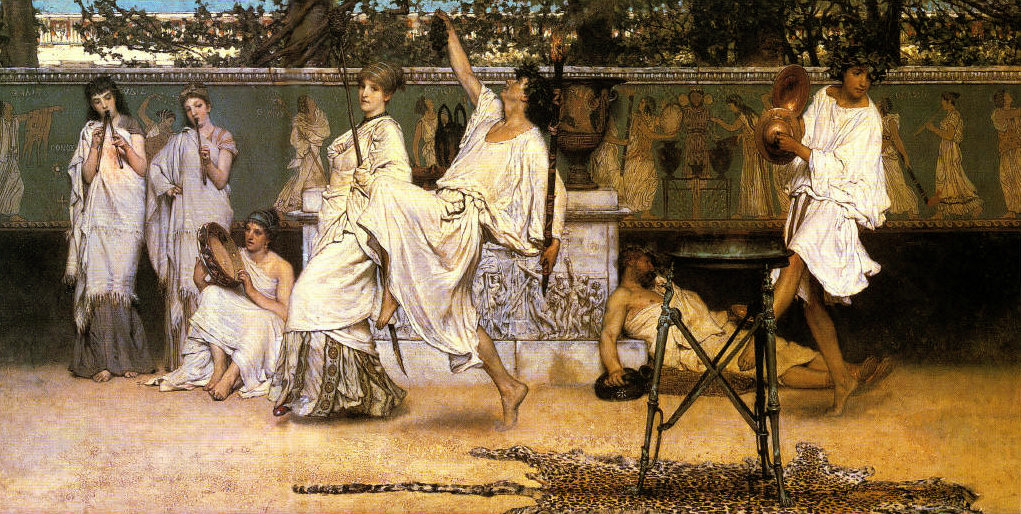

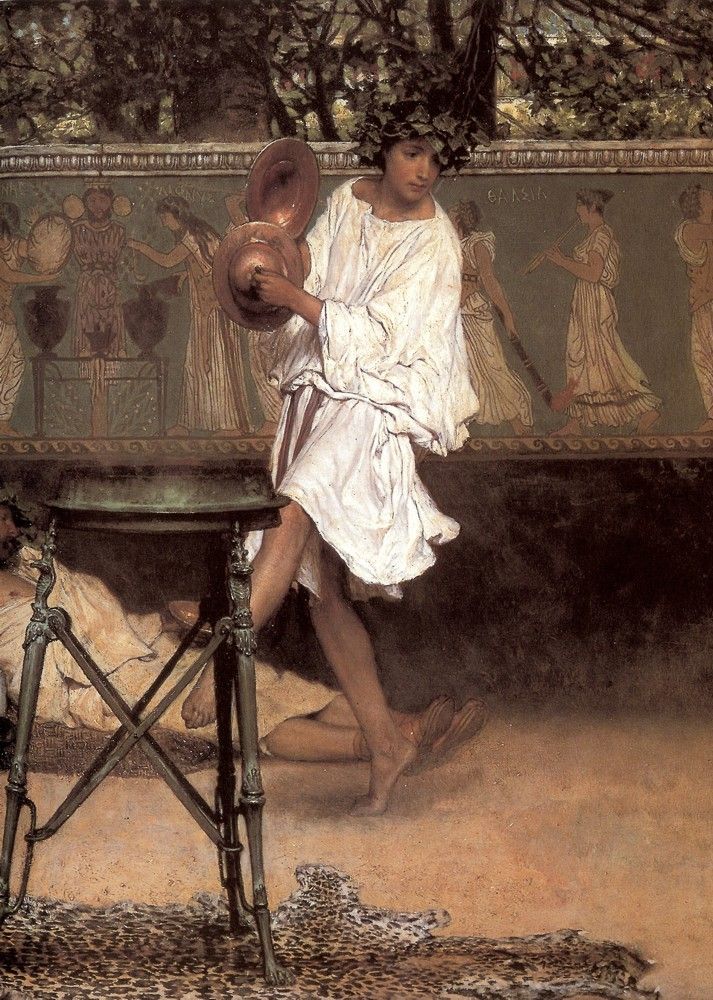

Two processions coexist in A Private Celebration. The foreground draws the viewer into an ongoing bacchanal with dancing bacchantes, musicians and a man succumbed to the pleasures offered by Bacchus. This dance procession is mirrored by the long frieze of an ancient bacchanal extended across the entire length of the painting. In antiquity, the procession honouring Dionysus or Bacchus, was an integral part of religious festivals, and these invariably unfolded into uncontrollable ecstatic dance.

The commanding woman next to the ardently enthusiastic celebrant entices the onlooker to join in with the festivities. It is impossible to resist her indisputable invitation. She carries a thyrsus; declaring her allegiance to the wine god Bacchus. But there is more than meets the eye. Alma-Tadema, as I explained in the previous post, united the unfamiliar, in this case Roman antiquity, with Victorian everyday life. The model for this female celebrant is none other than Alma-Tadema’s second wife, Laura. She, like her husband, was a trendsetter in London society; even dressed as a bacchante, she would have been recognized by any and all who viewed the painting.

The passionate figure dancing next to Laura holds a bunch of grapes in the one hand and a torch in the other. With apparent ease he balances on the ball of the foot; simultaneously the front leg soars upwards, which in turn is counteracted by a forceful backward tilt. Many years after this work was painted, Isadora Duncan, the great innovator of the modern dance, would perform similar movements. Just as a point of interest, Alma-Tadema was enraptured by Isadora Duncan when she performed in London in 1900. She became his artistic protégé. Duncan reminisces;

‘Alma-Tadema was my guide in the museums and pushed me towards the studies of ancient Greek vases which permitted me to reconstruct the movements of the antique dance’. *

The fastidiousness with which Alma-Tadema rendered the wall painting in A Private Celebration, states his fascination with classical art and illustrates his early Dutch training where he was instructed to paint with meticulous accuracy and precision. The wall painting is based on an Attic red-figure vase (stamnos), a work by an anonymous Greek artist, named the Dinos Painter. The stamnos represents gracious maenads dancing and making music approaching a totem portraying Dionysus. The images below offer an apt comparison between the painting and the Attic vase underlining the similarities and differences. Alma-Tadema clearly did not imitate existing art work; by choice they were a source of inspiration, revising them to accommodate his requirements.

Right: Stamnos, attributed to The Dinos Painter (active during the second half of the 5th century BCE) – Princeton University USA (lent from Archaeological Museum, Naples)

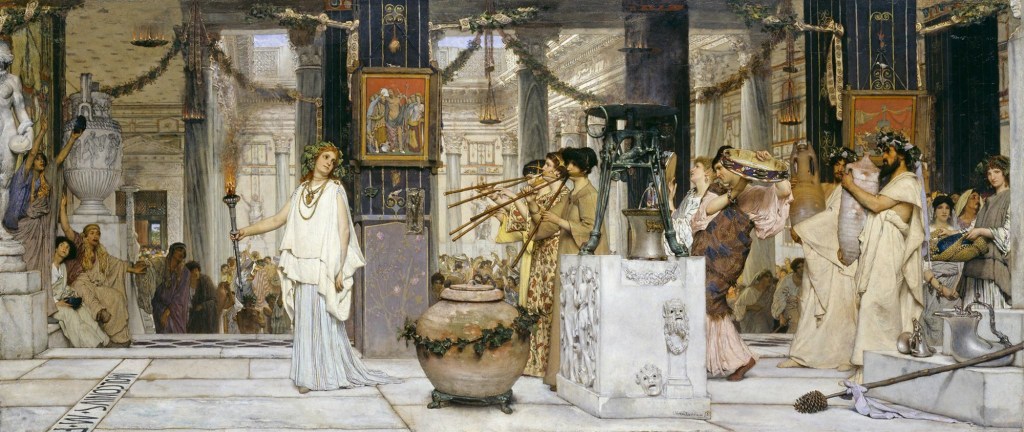

Every inch of The Vintage Festival has been painted with extensive attention to detail, Alma-Tadema including many items related to ancient Bacchic iconography. The painting shows a religious festival in honour of Bacchus taking place in an imposing indoor space; an ancient villa, profusely decorated with Pompeian and Roman art. In the front passageway a priestess heads a procession followed by worshippers; some play a double flute (tibia), and others a tympanum. The procession is, contrary to what you would expect in a Bacchus festival, subdued. The priestess has an air of serenity, and the celebrants, even the ones swinging with a tympanum, proceed in a disciplined, restrained fashion.

The calmness of the main scene practically conceals the turmoil taking place behind the colonnade. There, hardly noticeable, Alma-Tadema has painted a tumultuous dance happening. In the atrium, enclosed by delicately decorated columns, wall decorations and statues of heroic Romans, vast hordes of celebrants thrust, swirl, and dance, in an uncontrollable frenzy. The noise must be deafening; many are striking against the shields they are carrying.

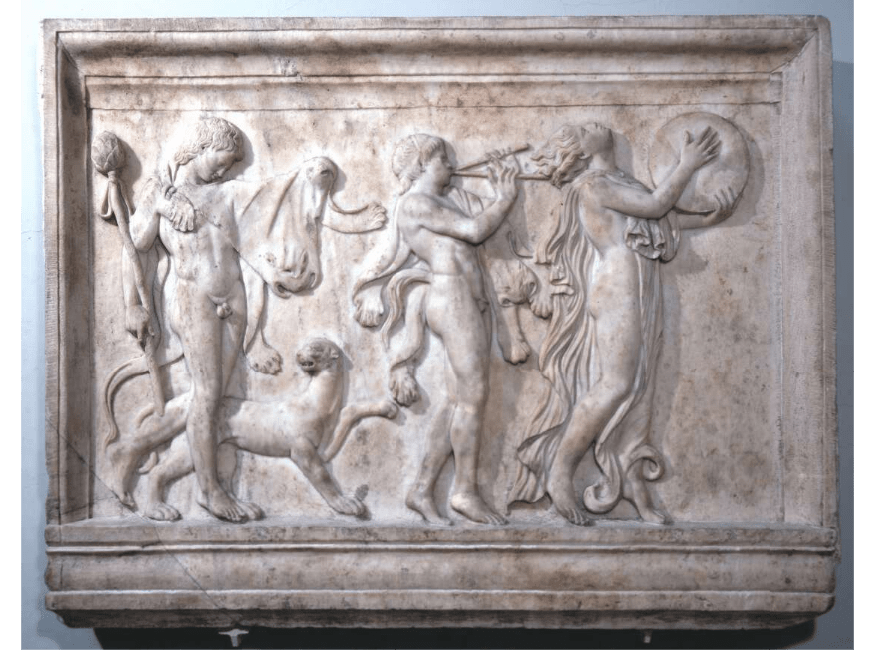

There is one more instance where dance appears unawares: this time on the huge marble vase, mounted on the massive pedestal. The scene is partially derived from a Roman marble relief, housed at The British Museum, of a maenad and two satyrs revelling during a Bacchic procession.

Centre: The Vintage Festival – Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg – detail of dance & vase

Right: The British Museum – Roman marble relief, a maenad and two satyrs in Bacchic procession c.100

If I may generalize for a moment, I could conclude that Alma-Tadema predominantly paints very restful, pensive, non-active figures. All the figures discussed in this post, for example, except for two lively celebrants in A Private Celebration, poise motionlessly. Though infrequent, there are paintings of maenads/bacchantes where the young women whirl, turn and move impetuously; often to the sound of the tympanum, they are beating. The primary subject of these compositions is the enraptured maenad/bacchante.

Right: A Garden Altar – oil on panel – 44.5 x 22 cm – 1879 – Aberdeen Archives Gallery & Museum

On the Road to the Temple of Ceres and A Harvest Festival, contrary to Alma-Tadema’s usual urban bacchanals, the festivities take place in the countryside respectively, near grasslands or in fields of harvested wheat. In the first painting, beside the leading figures, a group of worshippers meanders freely in the meadow. A Harvest Festival shows Ceres, the Roman god of crops and a group of followers near a fire; the bacchante dances alone.

A virtually identical woman, dressed in animal skins with long flowing hair, appears in both paintings. Their movements are remarkably similar. She prances from one foot to the other, barely touching the ground. Alma-Tadema, influenced by ancient sculpture, has introduced a bold thrust of her hip together with a forceful rotation of her torso, inducing a dynamic forward movement. You can practically hear the pounding and jingling of the tympana as she and the other bacchantes play with boundless enthusiasm. I managed to count at least five of these hand drums, and suspect that their racket combined with the various flutes must have caused quite a commotion.

The priestess of Bacchus portrayed in A Garden Altar rejoices in front of an altar; a statue of a couched Silenis stands in the niche. She performs her intoxicating dance with exuberance and unconfined physicality. This is not just a painting of a celebrant. A Garden Altar features a self-assured bacchante who looks straight at the beholder, welcoming all to join in with the revelry; a feeling that is enhanced by her enchanting, virtually seductive, smile. The dance is energetic, even wild; made obviously clear since her skirt soars freely backwards and her hair takes flight. Her body slants backwards to counteract her momentum; you can practically sense her spirals and undulations. Alma-Tadema has captured a split second, like a snapshot, of the rapturous priestess as she swirls along her ritualistic path.

Pomona Festival features a group of merrymakers dancing around a tree celebrating the feast of Pomona, the goddess of fruit trees, gardens and orchards, a minor Roman deity. All the figures, whether young or older, are high-spirited. The dancers are so vivacious you can see the dust flying up about their feet. Most spectacular is the celebrant who jumps high into the air; a most unusual contrast to the composed, pondering figures who frequent the greater part of Alma-Tadema’s oeuvre. Pomona Festival is timeless; the dress and setting suggest Rome, but people of all ages and all times, enjoy feasting and dancing; especially in a picturesque garden full of blooming hyacinths. Alma-Tadema here, and in many of his paintings draws parallels between ancient times and his own age; this point is emphasized even further knowing that the woman looking towards the beholder is, once again, the artist’s favourite model, his wife Laura.

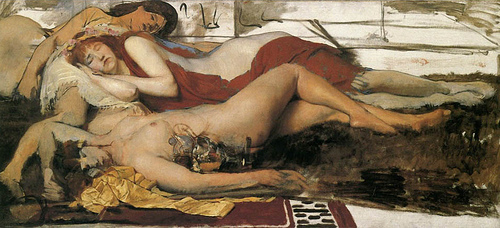

Even though dance may not represent a principal theme in Alma-Tadema’s work, he repeatedly turned to the dance of antiquity, in one way or the other. Spring and A Dedication to Bacchus, which I have not discussed in this post both, contain various dance elements. Likewise, the print, The Torch Dance, represents a charming version of an improvising bacchante. There are, furthermore, a number of paintings inspired by poems or prose; Alma-Tadema responded, in paint, to the writer’s allusions to dance. Or as in Exhausted Maenads after the Dance, where there is absolutely no dance to be seen, but the subject of the painting is the result of endless dancing.

* Isadora a Revolutionary in Love and Art – Allan Ross Macdougall – Thomas Nelson & Sons, New York, 1960 – p.54