Dance images are not the first thing you think about when browsing through a devotional or liturgical manuscript. And yet within these countless illuminated manuscripts, dance and dancers appear from time to time, not only, as I discussed in my previous two blogs, in The Hours of the Virgin, but also in other sections of a Book of Hours as well as in Breviaries, Graduals and Psalters.

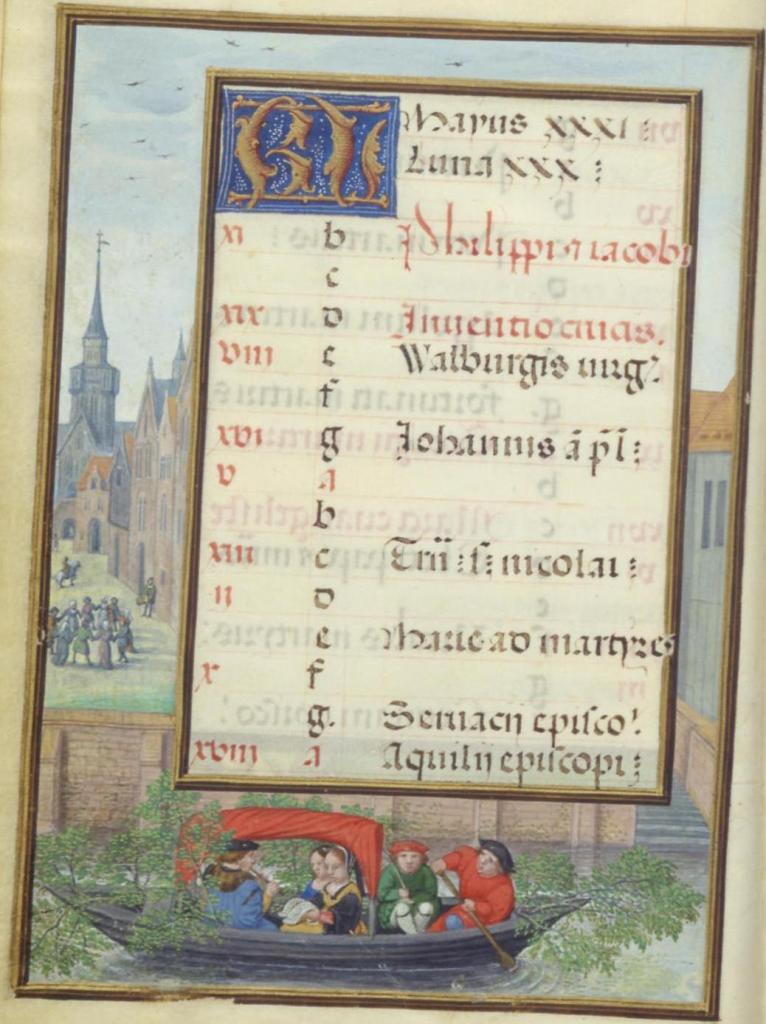

In a Book of Hours, images of dancers surface in the calendar section, the suffrage section and as border decorations. The collection of the Victoria & Albert Museum treasures a full-page miniature, most presumably once part of a calendar section of a book of hours. This single leaf, illustrating the month May, is painted by the illustrious Flemish artist, Simon Bening (1483-1561), also mentioned in the previous blog.

Simon Bening, slightly older than his contemporary Pieter Bruegel the Elder, presents a Flemish townscape where people from all levels of society are enjoying a festive day, possibly May Day, to celebrate the return of spring. The lovers in the boat, the storks that symbolize new life, the nobility on horseback carrying branches and the dancing all suggest a feast for the resurrection of nature after a long winter.

Passing up the stone stairs, into the town square we encounter adults and children standing in circular formations. The larger circle, of alternating men and women, stands motionless. Next to them is a smaller circle, all young children, who like their elders, stand quite still. Both groups are ready to start dancing, waiting for the music to begin or waiting in readiness for the nobility to pass through the town-gates signalling the start of the festivities. Where this full-page miniature is positioned on the page directly opposite an actual written calendar, the Waddesdon Manor folio, which has basically the same composition, becomes a border decoration surrounding the calendar itself. Just above the lovers sailing down the river, you can see a group of men and women, merrily enjoying a round dance. Unlike the V&A miniature where the group is stationary, standing with their feet uniformly placed together, this group is animated; one dancer stands astride, another steps forward and yet another raises his leg. Moreover, in the V&A miniature it is difficult to distinguish a musician, whereas in the Waddesdon Manor folio the musician, standing near a typical Flemish house, is actively playing a tabor and possibly a flute.

A closer look at yet one more similar example, Hours of Hennessy or Hours de Notre Dame , attributed to Simon Bening and his workshop shows the town folk actually dancing. This circular dance, no doubt a carole, is danced by men and women, holding hands, stepping and springing briskly to the rhythm of the musician’s tune. Contrary to the main figures, such as the nobility and those sailing in the boat, the dancing figures, in all three miniatures, remain anonymous. In each of these May calendar illuminations the dance scene forms, but, a minor section of the miniature. The dancing groups are always situated in the background, and are but a modest feature when compared to the lovers in the boats, the bridge, the nobility or the detailed architecture of the Flemish buildings. Small as they may be depicted, these dancers, dancing in an eternal circle, are significant in that they surely symbolize the enduring harmony of the community.

We now move from dancing in the town square to promenading in a great hall. The above miniature accompanies the calendar month February in a book of hours called The Golf Book. Simon Bening has presented a court scene, a feast, where a noble lady is escorted stylishly towards a grand aristocrat and his party. This distinguished lady, in striking red, is the only lady on the floor. Who is this lady? Undoubtedly a lady of some importance; on the left, we can see two curious characters peering through the doorway, not to mention a number of nobles awaiting her presence. One of the attendants has smothered his torch and proceeds to lead the lady forward; closer consideration reveals that is wearing a mask. His dignified poise together with his exceptional clothing, extensions flying from his sleeves, would suggest that he is a nobleman. The couple is accompanied by both a flutist and a musician playing the tabor. And to complete the puzzle a jester holds a marotte, a prop stick with a carved head, conspicuously between the man and his demure lady. One can only guess as to the couple’s movements, but considering the available floor space, the ladies’ voluminous dress, and the obstructive foot of the jester placed awkwardly right in front of the couple, their promenade would be none other than slow, stately and meticulous.

1 – Book of Hours – MS M.307.134r – detail & 2 – MS M.307.133v – Morgan Library & Museum – Bruges c. 1520

This festive jester, complete with bauble and bells, is a playfully nimble character who delights in high leg kicks. To his right a musician plays a light-hearted tune and to his left an oversized fly hovers over an equally oversized flower. This jolly border scene is placed exactly opposite a large miniature of The Mass of Pope Gregory where Gregory looks up towards the Christ of Sorrows; the sober and thoughtful are juxtaposed against the cheerful and fanciful. How different this manuscript is to the prestigious Les Belles Heures du Duc de Berry, (c. 1408), in which the famous Limbourg Brothers painted a miniature of two dancing girls tempting Saint Jerome. The two beautiful maids are so passive that they could just as well be statues; nothing in that miniature indicates that these enticing girls are even thinking about dancing. This manuscript was, not to forget, produced for the sophisticated French court.

The miniature of Saint Jerome is part of the suffrage section. These prayers, for the favourite saints, are found in nearly every book of hours. Generally, each set of prayers is introduced by a miniature containing both biographical and symbolic iconography of a particular saint. But, whether a book of hours originates from the Low Countries or elsewhere, dance images in the suffrage section, are few and far between. Below left, under a small miniature of Peter and Paul, two couples are dancing gallantly under the watchful eye of a soldier and a halberdier. The musician, as we have seen in different miniatures, plays a flute and the tabor simultaneously. And to the right, a pastoral scene of cheerfully dancing shepherds accompanied by a jovial bagpiper. All this takes place under a large miniature showing the Confessors before an enthroned Christ seated beside God. Moving into the background you can see a Flemish town and just a little further back is a typical windmill, still seen to this present day in the Netherlands.

Utrecht, today a major Dutch city, was an important centre of manuscript activity in the early 15th century. The superb, The Hours of Catherine of Cleves, produced in Utrecht around 1440, testifies to the absolute mastery of manuscript production in medieval northern Netherlands. This masterpiece contains no dance images, but, the Egmont Breviary, also made in Utrecht around 1440, has a colourful border illumination of two dancing shepherds elated by the angel’s message. These brightly coloured doll-like figures can be attributed to the Master of Otto van Moerdrecht to whom is also attributed a large number of the illustrations in the Dutch History Bible, also made in Utrecht around 1430 and now housed at the Royal Library in The Hague. The Master of Otto van Moerdrecht was interested in the illustrative aspect of dance; his dance figures, with the exception of the two shepherds, are stilted and only the musical instruments reveal that the figures are, in fact, dancing. The master does however leave a clue of recognition; besides the bright colours his frequently draws a stream in the foreground of his illuminations.

- Egmont Breviary – M.87 fol 103 -Annunciation to the Shepherds – Morgan Library & Museum – Utrecht c.1440

- Dutch History Bible – KB, 78D 38 I – f.150r – Jephthah, returning from victory (JUDGES) – Royal Library of the Netherlands – Utrecht c.1430

- Dutch History Bible – KB, 78D 38 I – f.156ra – Benjamites win wives from the dancing daughters of Shiloh ( JUDGES) – Royal Library of the Netherlands – Utrecht c.1430

The Flemish Psalter, a devotional manuscript of psalms, is richly decorated with miniatures, initials and border decorations. The text is enclosed by a gold coloured border filled with a multitude of different flowers, butterflies and insects complimented at the bottom of the page, bas de page, with illuminations which include scenes from everyday country life. One of the most vibrant is a group of villagers dancing around a tree on which some type of vessel is attached. Here we have a line dance where the participants hold hands and sink deeply through their knees. One wonders why? Perhaps they are playing a game of sorts; a man and a woman are carrying long sticks or just as plausible the artist has shortened the dancers so as to accommodate for the life-size flowers behind them.

In the hometown of Hieronymus Bosch, ‘s-Hertogenbosch, the Dominican Nicolaas van Rosendael, was known for the illustrative skills. The bas de page, shown below, is a detail from one of his two surviving works, both of which are housed in the Ghent University Library.

The scene derives from a gradual; the principal choir book used in the mass. Amid flowers and butterflies, under a small miniature of the Nativity, we see the familiar narrative of the annunciation to the shepherds. The angel, not visible in this detail, is hovering on the left border. Absolutely remarkable is how convincingly these shepherds dance. Especially impressive is the figure on the right who is either hopping or jumping with his leg lifted in the air. Even more telling is the swivelling rotation of the upper body. The Dominican must have observed dance often to be able to draw with such a degree of accuracy and sense of movement.

Centre: Gradual- s’Hertogenbosch – Nicolaas van Rosendael – Provided by Ghent University Library – 1515

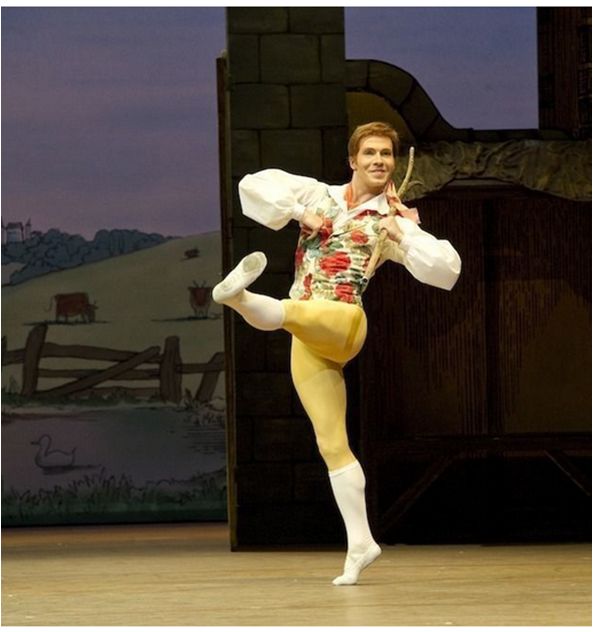

Right: Johan Kobborg – La Fille mal Gardée – chor: Frederick Ashton – credit Tristram Kenton, courtesy of Royal Opera House

The three images, shown above, underline how skillfully Nicolaas van Rosendael portrayed movement. The left dancer, a detail from the Flemish Psalter, shows a limited sense of movement when compared to the centre figure, created a mere fifteen years later. This lively shepherd swirls, has a flair for movement and displays perfect coordination just as the wonderful dancer Johan Kobborg on the right. I am not suggesting that the movements of these two dancers are exactly alike, but I am suggesting that both demonstrate vitality, exuberance and joy. And this zest for movement is exactly the sensation that the Dominican Nicolaas van Rosendael, peer of Hieronymus Bosch, captured in 1515.