Paintings by the Dutch artist, Hieronymus Bosch send chills down your spine. Nightmarish scenes of eerie creatures, sinners suspended on enormous harps, nudes skating in hell, bodies mutilated with knives and spears, fire burning down entire towns, gigantic ears and a multitude of bizarre, baffling and inexplicable shapes all inhabit his canvases. There is an extraordinary amount of documentation available about the paintings of Hieronymus Bosch. Over the years his works have been studied, analyzed and interpreted; many experts have attempted to explain his enigmatic work.

Dance and dance-related scenes appear in a number of Bosch’s paintings. Bosch is not interested in using dance motives as decoration. When Bosch paints dance there is a purpose. Dance, in the late middle-ages and early Renaissance, was associated with lust, the earthy and the depraved. Those dancing were bound for hell and damnation. Even though Bosch, at times, seems to paint pleasant, perhaps even carefree dance images, there is always an ominous message or a disturbing metaphor lurking. In Bosch’s work dance images foreshadow suffering, apprehension and doom. I distinguish four different types of dance images which I will discuss in upcoming blogs:

- Dancing peasants accompanied by a musician playing the bagpipes

- Weird dancing figures; human, partially human or fantastic

- The dance of death – reminiscent of Blind Death from La danse aux aveugles

- Exotic dancers – the moresca

Dancing Peasants

The three images below each show peasants couples dancing in the open air. On first sight the scenes are congenial; just peasants enjoying themselves, dancing to the sound of a musician playing the bagpipes. But first appearances deceive.

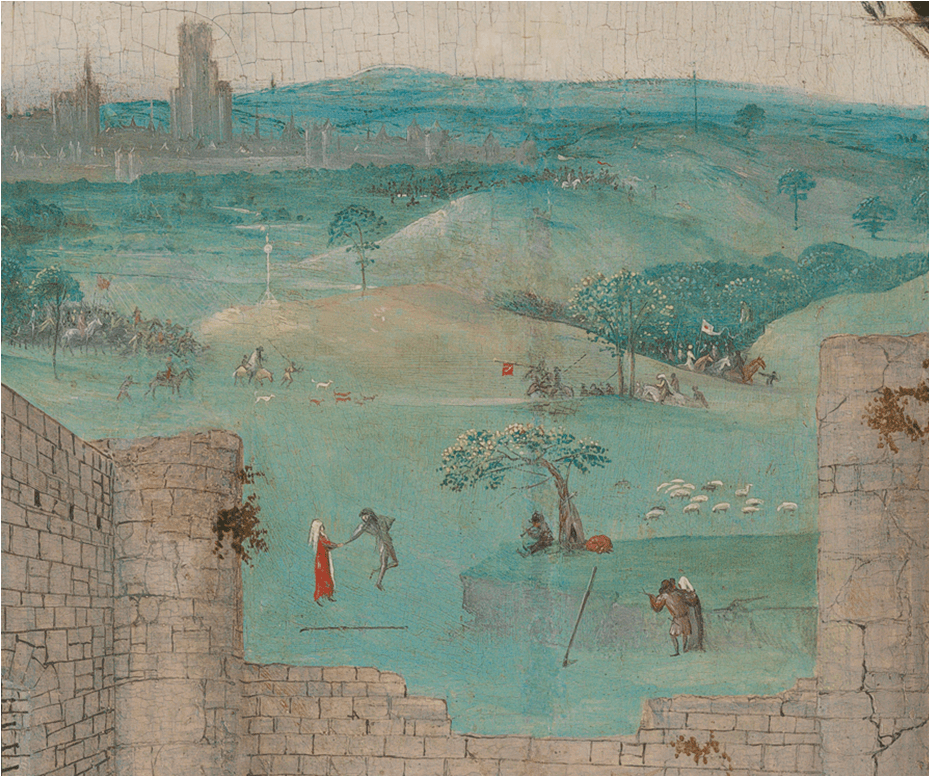

- Left – Hieronymus Bosch – The Adoration of the Magi – Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York c.1475 (detail) – click to enlarge

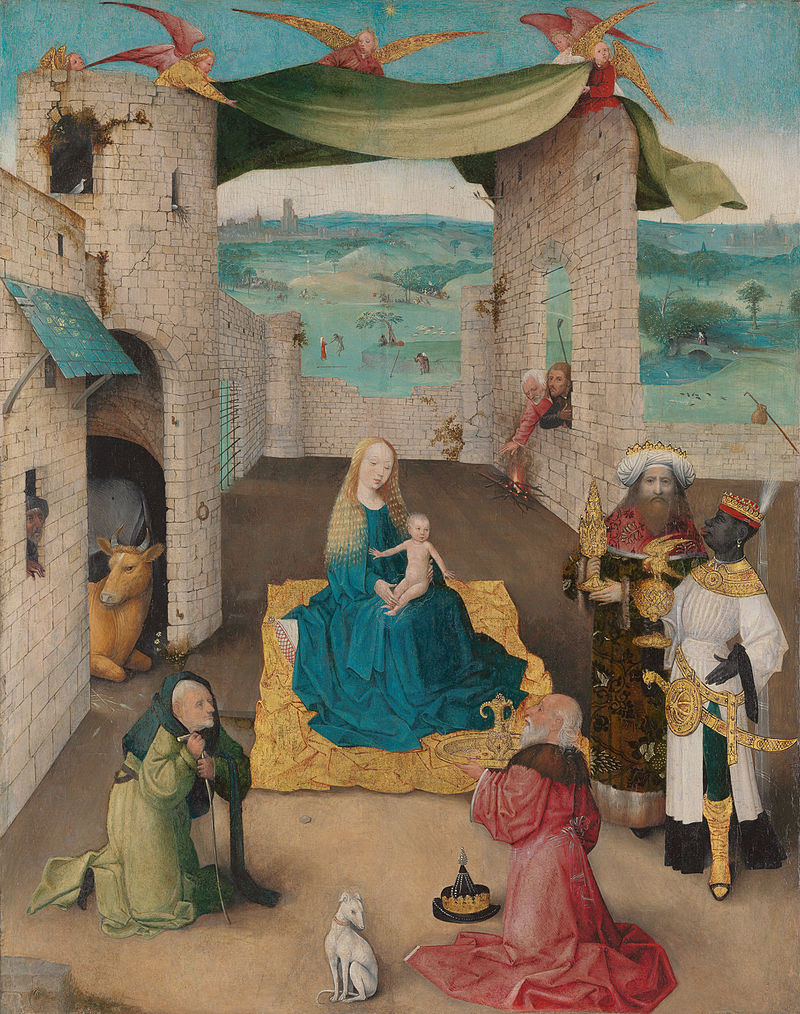

- Centre – Hieronymus Bosch – The Adoration of the Magi – Museo del Prado, Madrid c.1495-97 (triptych – detail of left panel) – click to enlarge

- Right – Hieronymus Bosch – The Haywain (outer panels) – Museo del Prado, Madrid c. 1515 – click to enlarge

To start with, the bagpipes are a problem. In early times this instrument had a bad reputation. Bagpipes were always played by a peasant, a jongleur or someone on the lowest scale of the social hierarchy. A musician playing a bagpipe will never appear in a miniature of an illuminated manuscript. David, for example, played a harp and angels only played celestial music. The bagpiper’s place was on the outskirts of the folio; in the margin. The bagpipe was the instrument of the common people: it was lewd, immoral, drawing allusions to male genitalia. The bagpipe was considered an instrument of hell; Bosch painted bagpipes in a variety of shapes and sizes often in combination with dance.

The Adoration of the Magi is one of Bosch’s early works. The Virgin Mary, who is holding baby Jesus, immediately catches your attention. The angels at the top of the medieval castle hold a drapery covering the open space between the remnants of the walls. As if through a tunnel our focus is directed into the vast landscape behind the Virgin. In the distance a shepherd, sitting under a tree, is playing the bagpipes. His dog lies idle not far from him. A shepherd and a shepherdess are not attending their sheep. The shepherd’s staff lies haphazardly on the grass. The man is young, has a handsome bearing and looking at the position of his legs we can presume that he is a light footed dancer. He is pulling his female companion but, she seems a little reluctant. The other couple is neither dancing nor listening to the music. Bosch has done little more than sketch these figures. To my mind, the man is attempting to charm his partner; the shepherd’s staff offering a vital clue. Not far behind them, masked by the hills, groups of soldiers on horseback are preparing for battle. All in all a disturbing situation; lasciviousness, impending combat and idleness juxtaposed against the beauty and serenity of the Epiphany.

In 1495 Bosch revisited The Adoration of the Magi creating a large triptych now to be seen at Museo del Prado, Madrid. Once again Bosch has placed a group of dancers in a devotional tableau. On the left panel, bypassing Joseph drying the nappies and moving into the landscape we meet two dancing couples accompanied by a peasant playing the bagpipes. Just for the record, there is a second bagpiper; you can find him on the roof, half seated, looking curiously at the arrival of the three magi.

Back to the dancers. In contrast to the earlier painting, these male peasants are older, shorter and stouter. The high shouldered man, on the right, with both hands on his waist balances earnestly on his wobbly legs. His movements are crude and coarse. One can practically imagine him treading heavily from one foot to the other. The peasant women, facing him, may be dancing, but I think she is just watching this weighty peasant as he shifts rhythmically to and fro. The peasant woman next to the bagpiper is definitely hopping or skipping and is doing her best to pull her hesitant male companion along. This pleasant dance scene is more than meets the eye. The sphere is threatening. Once again the landscape holds a disquieting clue. A scene of impending combat hovers above the stable and on the right panel a peasant is being attacked by a boar and a woman, looking very much like the women dancing next to the bagpiper, is trying to escape from a wolf.

There are many different versions of The Adoration of the Magi. Only the Prado version, generally considered as the authentic Hieronymus Bosch painting, has these four dancing peasants. Perusing through various paintings I noticed a similarity in the way that Hieronymus Bosch (1450-1516) and Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1526-1569) have painted the bagpiper and the dancer. In both cases, the musician, a somewhat older man, huddles over the bagpipes, keeps walking as he plays his instrument, keeps his knees bent and hides his face behind the pipes. The Bosch and Bruegel bagpiper could be copies of each other. And Bruegel’s male dancer, a major figure in the foreground of the canvas, is a stout fellow and no more light-footed than his Boschian ancestor.

- Hieronymus Bosch – The Adoration of the Magi – Prado Museum, Madrid c. 1495-97 (triptych – detail of left panel)

- Pieter Bruegel the elder -Dancing Mania at Molenbeek – 1564 – Albertina (Vienna) – detail

- Pieter Bruegel the elder – The Wedding Dance – Detroit Institute of Arts – 1566 – detail.

The last of the Bosch’s peasant dancers appear on the outer panels of the The Haywain. These shutters open to a triptych where Bosch addresses greed and the heinous ramifications to all those susceptible to greed. The outside panels prepare the viewer for the inside story. A peddler is walking over a rickety path. At his feet a ferocious looking dog. To the left a man, presumably robbed, is being tied to a tree. To the right of the peddler, a farmer and a shepherdess dance an improvised folk dance. The farmer has a little white bag hanging from his belt; this is used to carry the seeds for planting. The staff of the shepherdess lies on the round in front of them. Just behind them is a bagpiper, playing a spirited melody which incites the couple into a frisk dance.

We find ourselves viewing an odd situation. If we can forget the impending doom of the peddler and the abuse of the man being tied to the tree we might even think that Bosch painted a peasant couple who are enjoying themselves in a frolicking dance. But Bosch never uses dance as mere decoration nor does he ever use dance images merely as innocent amusement. To dance was lascivious. Dancing lead to lustful behaviour and lust, just as greed, is one of the cardinal sins. This dancing couple are sinners, symbolizing eroticism and depravity and just as the crude bagpiper, will suffer. The gallows on top of the hill is a harrowing premonition of their fate.