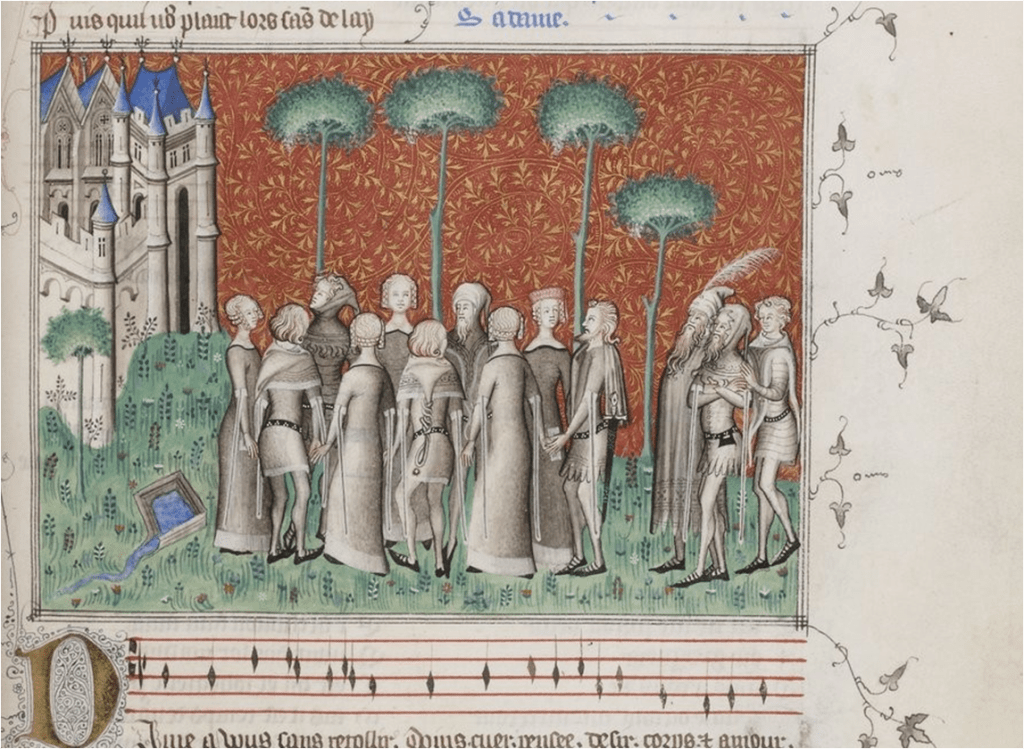

Love teaches a young poet to compose music. He presents his song, a somewhat outdated lai, to his beloved. Not entirely content with his work and dissatisfied by his awkwardness, the poet flees and complains brazenly to Fortune. Fortuitously for him, Hope arrives and helps him to compose, a fashionable virelai to enchant his lady. The miniature below shows the poet and his two friends approaching the castle, to find his lady singing and dancing with her companions. It captures the moment just before the poet presents, his most recent composition, the virelai, to his lady. The lady and her friends perform a graceful court dance; the men and women alternating, forming a circle. The women’s dress is simple, just a smooth, straight gown decorated with a thin black border. Their vertical stance and unwrinkled dresses give the impression that they are walking or strolling. The position of the men’s feet and legs offer very little information; they too seem to just walk or make small steps on the spot. The dancers are tinted in a grayish hue and each personage has original and distinctive facial features, hairstyle and headdress.

The miniature shown above, enhances one of the oldest known manuscripts of Le Remède de Fortune, written by French poet /composer Guillaume de Machaut (also spelled as Machault). The manuscript is a collection of Machaut’s work and includes various medieval love poems, including Le Remède de Fortune and Dit dou Lion.

After the marriage of Philip the Bold, Duke of Burgundy to the daughter of Louis of Mâle, Margaret of Flanders in 1369, the ties between France and Flanders grew tighter. In the mid 14th century, the Flemish miniaturist was in considerable demand at the French court; many Flemish artists worked and flourished in Paris. The creator of the above dance miniature was of Flemish origin; an anonymous artist who has been named the Master of the Remède de Fortune. He and other Flemish artists working in France remained true to their Flemish roots, incorporating the distinctive Flemish realism into their work. To illustrate this point I have, as an exception, included a non-dance miniature which may be the work of the master or the work of one of his associates. The animals and the woods are no longer fantasized but are rendered as lifelike. Rabbits, foxes and trees are placed in a setting suggestive of a more realistic environment.

R – BnF fr.1586 f. 103r – Guillaume de Machaut – Dit dou Lion- The enchanted garden c. 1350-55 (detail)

The narrator in Dit Dou Lion, (also written as Dit du Lyon/Lion), arrives at an enchanted island where a lion guides him in his pursuit to find a fair lady. The two miniatures, shown below, illustrate this love poem; both are attributed to Flemish miniaturists. The illustration of the line dance (BnF fr. 1586) originates from the same manuscript as the illustration of the stately circular dance, shown at the top of the page. These two miniatures bear various similarities; the costumes and shoes are identical, and the dancer’s faces are almost interchangeable. In both miniatures the dancers move leisurely, even elegantly. The background is equally interesting; the miniature showing the line dance is set against a wall of beautifully decorated blue tiles. The background for the circular dance is more unrealistic. This dance is placed in front of a reddish wall covered in curvilinear shapes. The combination of this ‘wallpaper’ with a castle exterior and various forms of foliage is rather strange, to say the least.

R – BnF fr.1584 f.92r – Guillaume de Machaut – Dit Dou Lion – 1372-1377 (detail)

A grassy hill with one meagre tree forms the background for a group of dancers in BnF fr.1584. The artist, working in the vicinity of Flemish artist, The Master of the Bible of Jean de Syr, has chosen to illustrate the dance scene with four men and four women in what appears, at first sight, to be a circular formation. This is, however, a most extraordinary circle. Some of the dancers face sideways, some face the front, some have slightly turned to their partner and yet another has his back to the reader. The hands are joined as you would expect in a carole, but held in a most peculiar way. The dancers are not particularly delicately drawn, yet the figures of the front two women are well-proportioned, boasting tiny waists and full bosoms. The shapely physique of the male dancers, with their narrow waists and puffed-up torsos, is overtly exaggerated, and their skinny legs and extended footwear (poulaines) disclose little about either the steps or the movements.

Flemish artists were the earliest miniaturists to explore visualizing perspective on a two-dimensional surface. Take the line dance, for example: the blue receding background gives the impression that the lightly clad dancers are nearer to the reader. The miniaturist takes yet another approach in the carole miniature. He places the dancers on an ascending slope; the back dancers are placed higher than the front ones, giving the illusion of depth.

Especially striking are the dance related words, placed in the text immediately under the miniatures. The words ‘karoler‘ and ‘caroler‘ may refer to the familiar dance the carole, but it may also refer to the general concept of dance or dancing. Other dance-related words like ‘dancier‘ and ‘baler’ already appear to be in common use in the 14th century.

Les Voeux du Paon, MS G.24 – Morgan Library and Museum *

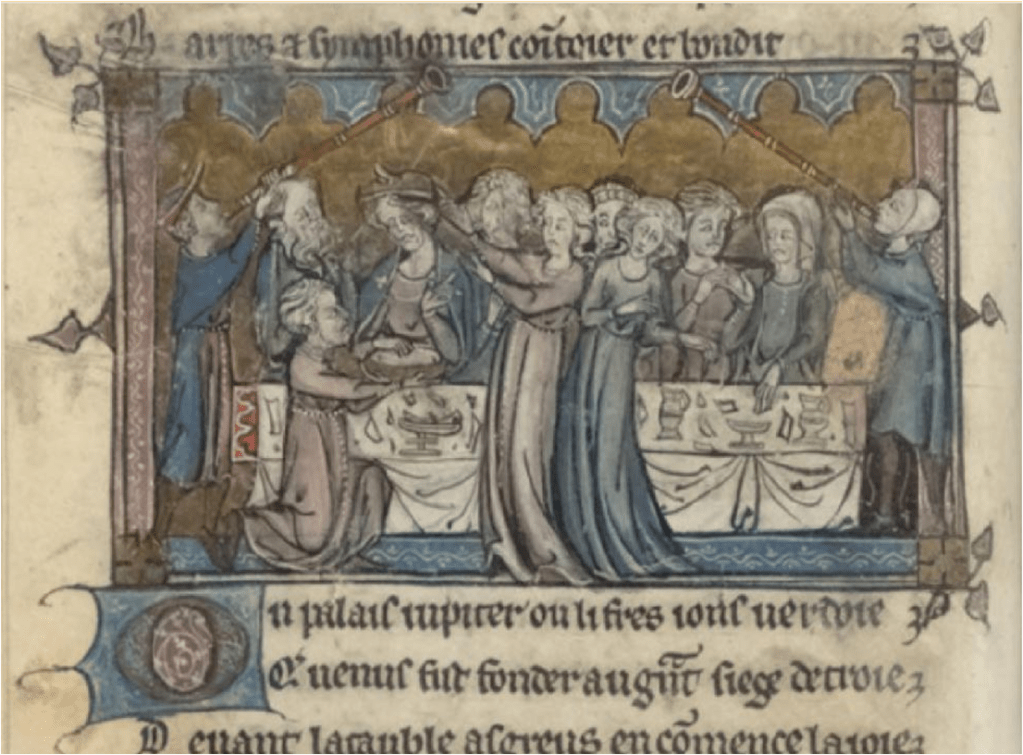

Les Voeux du Paon, an immensely popular 14th century poem, was written for Thibaut de Bar, Bishop of Liège by Jacques de Longuyon in 1312. It is a lengthy two-part poem. The first section relates the tale of Alexander the Great opposing the wicked king of Ind, Clarus. The second section leads to a splendid banquet where knights associated with Alexander take vows upon a peacock. There are many extant manuscripts of Les Voeux du Paon, but only three have marginal decoration. A very famous copy of Les Voeux du Paon is interpolated in the Romance of Alexander (Bodleian 264), a profusely illustrated manuscript with miniatures and marginalia about which I have written in two previous posts. A second manuscript, sometimes called the Glazier Peacock (Morgan Library & Museum MS G.24) contains no dance miniatures, but a large array of marginal figures from dancing apes, entertaining musicians, hybrids, headless characters, grotesques and a tabor playing crowned king with a cone like headdress dancing tip-top on the edge of the foliage. Both of the above-named manuscripts contain various miniatures of the banquet scene where the peacock is displayed with pomp and ceremony, but none show dancers, even though the text specifies that ladies and maidens are dancing. The third manuscript, an early 14th century work now in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, contains a miniature illustrating the banquet feast with two ladies dancing to the sound of buisines.

Practically every manuscript of Les Voeux du Paon contains a miniature illustrating the banquet scene with the knights performing a ceremonial vow to the peacock. Birds, especially swans, peacocks and pheasants, featured in the lifestyle of the medieval court. The swan enjoyed a unique place in the Arthurian tales. Percival, knight of the Holy Grail, was sent to rescue a maiden in a boat pulled by swans. King Edward 1 of Great Britain, held the Feast of the Swans in 1306 where 267 lords were knighted at Westminster Abbey. The knights swore an oath before two swans. A bird oath, be it to the swan, the peacock, or the pheasant, was reserved for the most celebratory events, such as the chivalric celebration in Les Voeux du Paon. One such extravaganza, known as the Feast of the Pheasant, took place in Lille in 1454, as part of the preparations for an imminent crusade to the Holy Lands. This spectacular feast, abounding in food, music, and dance, was hosted by Madame d’Estampes in the presence of Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy and his wife Isabelle of Bourbon. During the evening, knights swore the traditional voeux du faisan, or “oath on the pheasant.”The following painting, illustrating this great feast, was created by an anonymous artist a century after the actual event.

On the left-hand side, the artist presents a column of text informing the viewer of the date, the place, and which royalty attended the festive occasion. All the guests present are beautifully attired and some bear large torches. Judging by the cheerful expression of the two dancing couples, the musicians must be playing a delightful melody. The two front couples dance in perfect unison. All the ladies are extremely elegant, though their cumbersome dresses leave them less buoyant than their lively partners. And those headdresses, especially that of the lady on the right, will no doubt hinder excessive movement. The artist has painted a dignified court dance, possibly the basse danse; the most fashionable dance in the 15th and 16th centuries.

R – Anonymous after Hieronymous Bosch – The Marriage Feast at Cana – Museum Boijmans van Beuningen, Rotterdam – detail – 1550

A statue of a swan with its wings widespread stands in the Dutch city of ‘s-Hertogenbosch, home town to Hieronymus Bosch. The swan hovers over the Swan Brothers House, home to the Illustrious Brotherhood of Our Blessed Lady, a brotherhood founded in 1318. Traditionally, at festive banquets, a swan was served to their elite guests. Members of this society have included William of Orange, and the distinguished painter, Hieronymus Bosch.

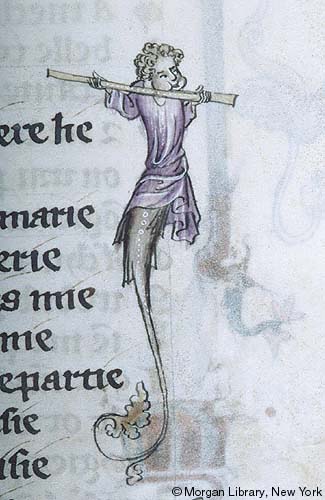

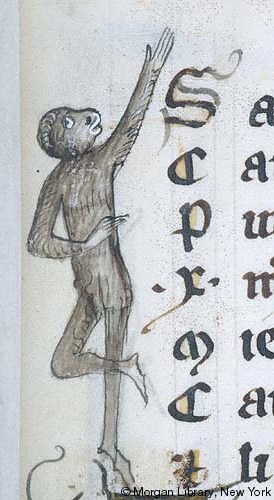

* Les Voeux du Paon, MS G.24 (The Vows of the Peacock)– Morgan Library and Museum (marginalia from left to right)

a: folio 94r – an ape plays a straight trumpet

b: folio 106r – a hybrid man plays a flute

c: folio 106r – an ape dancing

d: folio 121v – a crowned man dancing, playing a tabor and pipe