One of the most popular themes in 16th and 17th century Flemish art was the village festival. Artists from Pieter Bruegel the Elder to David Teniers the Younger illustrated village life featuring peasants drinking, frolicking, dancing and enjoying themselves. The artists painted spacious village squares brimming with exuberant peasants. It was not uncommon to spot a few elegantly dressed burghers amid the boisterous activities. These townspeople rarely blend into the crowd. They remain at a distance, observing rather than participating in the festivities. Who are these atypical visitors? What motivates town dwellers to visit a rural village? Did the artist incorporate them as embellishment, or do they serve a purpose?

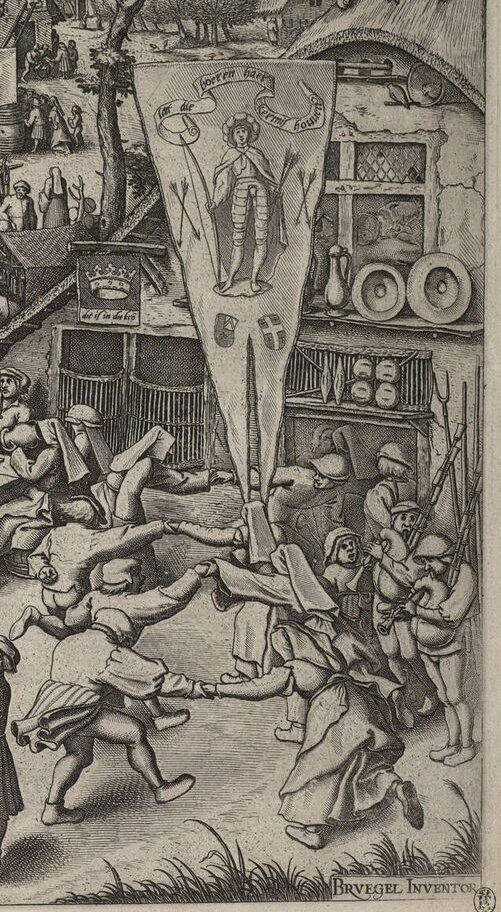

The Fair of Saint George’s Day – etching and engraving – 33.6 x 52.4 – 1559-61 – Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Printed by Johannes of Lucas van Doetechum after Pieter Bruegel the Elder, published by Hieronymus Cock.

The above print, after Bruegel the Elder, depicts a kermis where village folk celebrate a religious holiday in honour of Saint George. Children are playing games, a stage is erected on beer barrels, and there is a mock battle with a dragon, a sword dance, and couples dancing near the tavern. Everyone is busy except for the two rustics seated on a bench in the left foreground and the two well-dressed men standing in front of the tavern. The latter are town dwellers who take no part in the activities. They merely observe. The man on the right points his arm in the direction of the village square, as if to share his thoughts with the audience. Is the spectator enjoying or criticising the festivities? And Bruegel? Does he approve of the festivities, or is he mocking peasant life? The text on the banner, “Let the Farmers Have Their Fair”, might offer some clarity, or add to the ambiguity.

Left: Detail of the spectator relating to the audience

Right: Detail of the dancers and the banner with the text “Let the Farmers Have Their Fair¨.

What appeal would peasant frivolities hold for these affluent individuals? Perhaps they are seeking entertainment, a change of scenery, or an opportunity to buy the produce at the local markets. Or possibly there are other reasons. These wealthy people meander through the village square. They keenly observe the various spectacles but distance themselves from the common people. There is, it seems, a certain wry amusement in watching rustic folk drink, dance, and fool around.

The work of the Flemish artist Joachim Beuckelaer (c. 1533 – c. 1570/4), a pupil of his uncle Pieter Aertsen, was groundbreaking. He was one of the first artists to position ordinary working people at the heart of his composition. He tackled everyday themes with honesty, highlighting a kitchen maid or a vegetable vendor. Beuckelaer specialised in kitchen and market scenes. Dance rarely appeared in his work. To my knowledge, Beuckelaer’s Rural Festival is his only work with dancers: a line dance takes place behind the trees, and a bagpiper, as you would expect at peasant feasts, accompanies the dancers.

Rural Festival is not a typical Beuckelaer work. Rather than emphasising working figures, the focus is on the fashionable townspeople. The peasant activities merely form the surroundings for a group of distinguished guests. Three refined women gaze directly at the audience. The centre woman is escorted by two men. She appears rigid and somewhat uneasy. There is also a couple riding on horseback. And how should we interpret the actions taking place in the horse and carriage?

Rural Festival – oil on canvas, transferred from wood – 113 x 162 cm – second half of the 16th century,

Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg

Breuckelaer establishes a clear division among the social classes. The affluent people in the foreground are brightly illuminated, and their facial expressions are clearly visible. They relate with the audience. The villagers in the background are depicted with less precision, though they are unified by earthy hues. The only exceptions are the beggar lounging in the foreground and the young maid who has averted her gaze modestly to the ground. Breuckelaer appears to place modesty alongside haughtiness and contrasts wealth with poverty, thereby further highlighting the social status of the visitors.

The visiting townspeople are by no means the first figures you discern when presented with Jan Brueghel the Elder’s spacious view of a long street with an adjoining landscape. The view, taken from a high vantage point, reveals a myriad of people feasting. Jan Brueghel paints the figures meticulously, whether they are entering the church, sitting at the tavern, or dancing in the street. Likewise, the castle, the foliage, the figures, and the animals resting on the riverbanks are rendered in detail.

Dance on a Village Street – oil paint on copper – 47.5 x 68.6 cm – 1600 – Royal Collection, London

The dancers are the focal point. Most obvious is a delightful line dance led by a sprightly young man. He is followed by a chain of dancers. This choreographically uncomplicated dance is suitable for all ages. Even small children can join in. There are several couples dancing in the foreground. Some perform movements reminiscent of Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s iconic dancers. Others join hand in hand, typical of a folk dance stance. These vivacious dancers have caught the attention of a stately gentleman and his wife; both look intently at the dancers. Their dark, prudent attire clarifies their reservations. It is obvious that their religious beliefs reject dancing; dance and other forms of frivolity are considered moral sins. Still, the endearing young girl tries to pull her father closer to the dancers.

Detail of dancers and towns people – Dance on a Village Street – 1600 – Royal Collection, London

Autumn Landscape – oil on canvas – 116 x 198 cm -Kunsthistorische Museum, Vienna

The painting, Autumn Landscape, presents a bird’s-eye view of an extensive countryside. The peasants, celebrating the bountiful harvest, play games, feast, visit the market, and enjoy the open-air theatre. And how they dance! The jolly rustic folks are swinging their legs effortlessly in the air, dashing around in a spontaneous circle. Their impromptu actions are a marked contrast to the cluster of rigid townspeople. These respectable, devout citizens are typically dressed in black. They move slowly, refrain from participating in the dancing, and observe the dancers with an air of superiority. In the distance, another group of townspeople meanders, much like the central group, placidly through the landscape.

Autumn Landscape – detail showing dancers and townspeople – Kunsthistorische Museum, Vienna

In the animated village scene, The Grand Kermesse of Saint George, created by the Flemish artist Peeter Baltens (c. 1527-1584), figures are engaged in various activities. Baltens, a contemporary and associate of Pieter Bruegel the Elder, included typical village scene characters: the woman dragging her drunken husband home, a man relieving himself, and children at play. And there is also a group of dancers cavorting around a maypole. However, do not be deceived by this cheerful village setting. Despite all the pleasantries and amusement, this artwork also illustrates several vices. Dancing, at the time, was not regarded as a virtuous activity and is classified alongside vices such as drinking, gluttony, theft, violence, and gambling — all depravities highlighted in this artwork. In 16th-century village scenes, the townspeople usually distance themselves from the villagers. In The Grand Kermesse of Saint George, Baltens takes a different approach. He prominently features some wealthy individuals gambling with the locals; the affluent, like the peasants, are prone to vices. Fortunately, there is also an opportunity for redemption; a devout couple has turned their backs on the ‘unpleasantries’, preferring instead to watch the congregation as it enters the church.

The Grand Kermesse of Saint George – oil on panel -87.5 x 132 cm – 16th century – De Jonckheere Master Paintings, Brussels

Jacob Grimmer (c. 1526 – c. 1590) was a distinguished landscape painter. He depicted realistic landscapes with typical Flemish villages and farmhouses. Grimmer’s painting, Entrance to a Village with Peasants Carousing, is divided into two sections by a curving diagonal line. The artist has positioned an elite company in the shadowy foreground. There, seated couples listen to a gracious lady playing a lute and watch a gallant couple promenading on the lawn. There is also a refined couple on horseback. They are about to cross a low bridge, which not only serves as the entrance to the village but also forms a bridge between the upper and lower social classes.

Entrance to a Village with Peasants Carousing – oil on oak panel – 50 x 77 cm – 1586 – Web Gallery of Art, Private Collection

On the other side of the bridge, Grimmer depicts a typical Flemish village complete with tavern, church, and market stalls. The long red pennant hanging from the tavern’s flagpole suggests that the villagers are celebrating the feast of Saint George. We, the viewer, stand at a high vantage point and overlook the entire landscape. Even though the figures are small, the movements of the dancers are readily distinguishable. There are four couples dancing in a double-row formation near the tavern. They are accompanied by a bagpiper. Furthermore, there is a group of men performing an exciting sword dance in the centre of the village. Without a doubt, this section of the painting will remind you of Bruegel’s The Fair of Saint George’s Day. The two visitors I discussed earlier are also present. However, the specific arm gesture and facial expression of the visiting man are indistinct.

Grimmer, and most Flemish artists, clearly differentiate between the pictorial representation of wealthy townspeople and rural folk. The most obvious difference is the clothing. The wealthy wear elegant, heavy attire, which coincides with a refined, effortless appearance. The rustics sport simple clothing. The women have short skirts, allowing them to jump and turn with ease. There is also a marked difference in deportment. The peasants’ movements are rough. When they dance, they fling their legs into the air, curving their torsos and lifting their arms well above their heads. The townspeople are well poised. They are tall, slim, and self-assured. They promenade; they stroll but never dance. In fact, these people are never shown breastfeeding a baby, in a state of intoxication or, heaven forbid, relieving themselves.

Finally, I must draw your attention to the musical accompaniment deemed appropriate to specific social classes. The bagpiper only accompanies rustic dance. Why? Apart from his uncouth appearance, his cheeks bulge when he plays the pipes. Such a ‘hideous distortion’ is intolerable in a sophisticated society. Additionally, the bagpipe has long been regarded as a symbol of human folly; its design closely resembles male anatomy. The elite favoured string instruments such as the lute, the harp or the viola da gamba. The musician could play these instruments with grace and maintain a genteel poise.*

Peasants Dancing Outside a Country House – oil on panel – 83.5 x 126.4 cm – 1645 – Royal Collection – Buckingham Palace

Since the time of Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Flemish artists have included elite visitors in their village scenes. There is no one specific reason for their presence. At times, they are simply enjoying country life; sometimes, they serve as a commentary on village life. Frequently, they illustrate ‘proper ethical conduct’. David Teniers the Younger presents yet another perspective. The elite figures in the above painting form a group portrait of the residents of the country estate. Teniers intertwines the affluent with the rural folk. One of the rustics encourages a young lady to dance, and the wealthy boy joyfully dances alongside the rural folk. The musician is unique. He stands atop a beer barrel, the traditional place for a bagpiper. Nevertheless, he is elegantly attired, handsomely poised, and performs on the violin. Townsfolk are regular guests in Teniers’ work. His fascinating paintings are the subject of the following post.

* For a more detailed discussion on musical instruments, see Peter Bruegel and the Art of Laughter by Walter S. Gibson – pages 90-95 – University of California Press ISBN 10: 052045210 published 2006