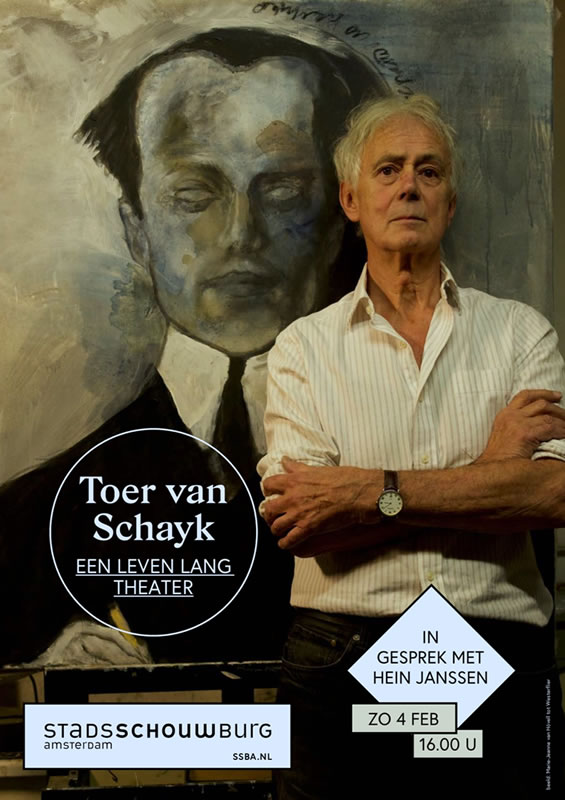

The celebrated Russian dancer Vaslav Nijinsky (1889-1950) is a continuous source of inspiration for the prolific Dutch artist, Toer van Schayk (1936). Van Schayk is a man of many talents. He was an exceptional dancer. To this very day, he is a sculptor, a painter, a choreographer, and a designer who approaches each creative discipline with unwavering artistry. This erudite artist, who has spent his entire life in the theatre, can only be described as a Renaissance man. Van Schayk’s work is well documented, yet his passionate fascination with Vaslav Nijinsky, a red thread that meanders through his personal and artistic path, is not as widely known.

Van Schayk, similar to all others in our generation, did not see Nijinsky perform live on stage. However, his grandmother did. Her stories of the remarkable Ballets Russes dancer captivated Van Schayk’s mother, who then instilled her enthusiasm in her son, Toer. Van Schayk recalls that prior to taking his first ballet classes, he had read every book available on Nijinsky. The legendary dancer transformed into his idol and subsequently became essential to his artistic identity.

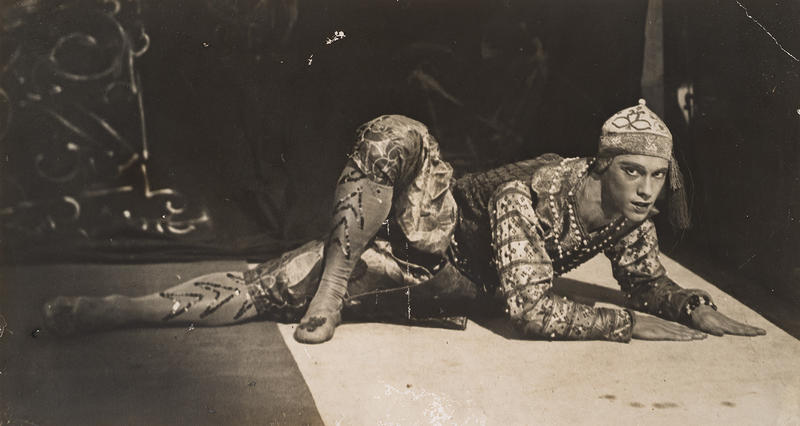

Vaslav Nijinsky is regarded as the greatest male dancer of the early twentieth century. As a member of the Imperial Ballet (later Kirov, now Maryinsky Ballet), Nijinsky encountered the extraordinary impresario Sergei Diaghilev (1872-1929). Diaghilev, at that time, was organising a season of Russian ballet in Paris. On Diaghilev’s request, Nijinsky performed in the first season of the Ballets Russes in 1909. He was a phenomenal success. The next year, Nijinsky danced the role of the slave in Scheherazade. Both the audience and critics were overwhelmed. Nijinsky was acclaimed as ‘le Dieu de la Danse’.

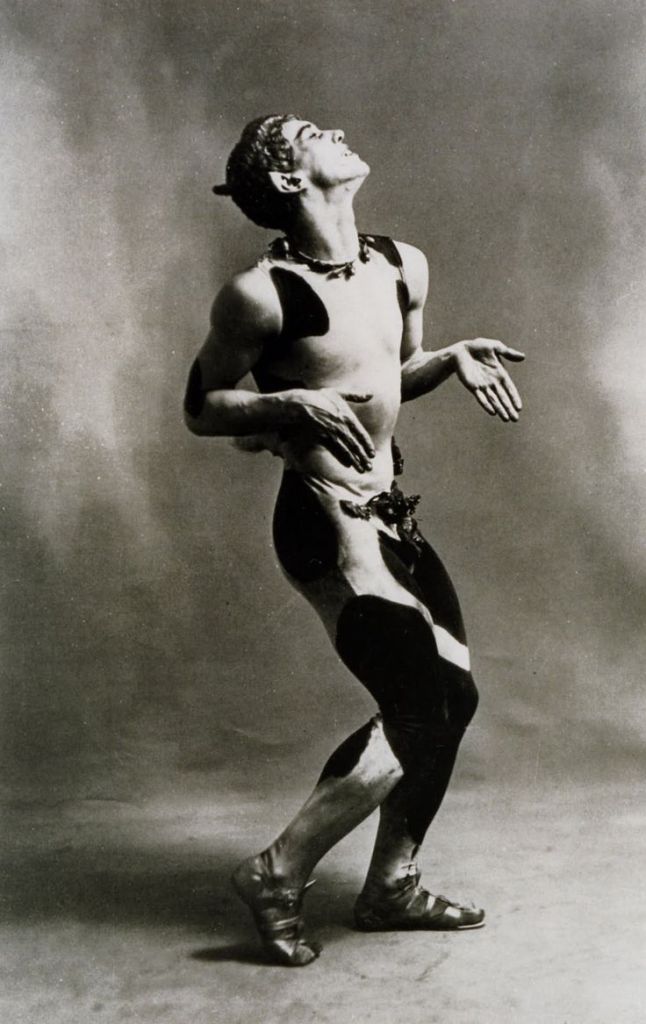

Right: Vaslav Nijinsky as the Faun in L’ Après-Midi d’un faune – 1911 – Photo Baron de Meyer

An intimate relationship developed between Diaghilev and Nijinsky. Diaghilev, seventeen years Nijinsky’s senior, supported the young dancer artistically and financially, coaxing him into choreography. Nijinsky, famed for his extraordinary ability to jump, created four innovative choreographies – including L’ Après-Midi d’un Faune, Jeux, and Le Sacre du Printemps – based on dance forms foreign to his academic training. The ballets were highly controversial.

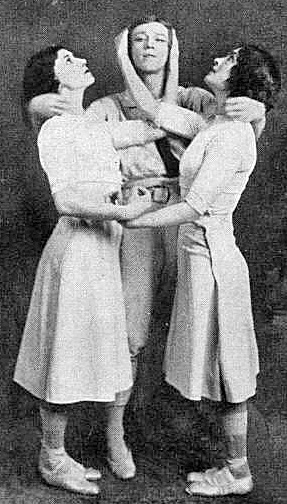

Left: L’ Après-Midi d’un Faune (1912) & Right: Jeux (1913) – photo Charles Gerschel

The quiet, withdrawn Nijinsky married the Hungarian aristocrat Romola de Pulszky in Buenos Aires in 1913. Diaghilev, enraged by Nijinsky’s betrayal, dismissed his star dancer. In 1919, Nijinsky wrote a diary expressing his innermost thoughts and emotions. He had suffered a psychotic breakdown. Gradually, Nijinsky retreated into his world, remaining there for the rest of his life.

The lauded Nijinsky, who fascinated Toer van Schayk and other artists, playwrights, filmmakers, ballet enthusiasts and poets, is the tragic story of an exceptional man: an unprecedented dancer, Diaghilev’s lover, an incredibly bold choreographer, the author of an astonishing yet elusive diary, and thirty years of mental confinement. A remarkable life that, even during his own time, became a legend.

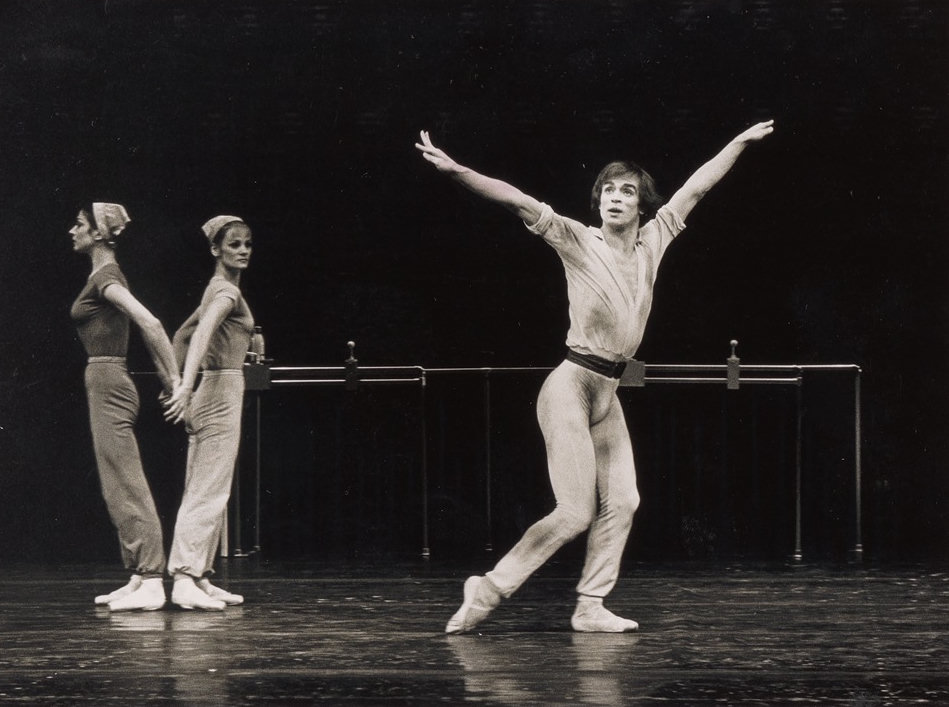

Toer van Schayk embraced the legend. Early in his choreographic career, he created Jeux (1977) and Faun (1978) using the same Debussy score as Nijinsky’s famous works. Even though Van Schayk’s ballets are innovative, they still evoke the ambiance found in the original creations. Van Schayk’s Jeux studies the relationship between five people. There is a young man flirting with a young woman. They are joined by a second woman. Completing the quintet is an older man (the gardener) and a younger boy. Their relationship is tender. In the original Jeux, a ballet for three dancers, Nijinsky mirrored a tennis game. He was the first choreographer to incorporate movements directly inspired by sports. His work explored the dynamics between a man and two women.

Left : Jeux – 1977

Right : Faun – 1978

Van Schayk created Faun for Rudolf Nureyev. The ballet is set in a dismal factory where two women, danced by Alexandra Radius and Maria Aradi, toil away on an assembly line. They perform their repetitive tasks in a robotic manner to the sound of blaring popular music. Nureyev, furnished with a supermarket stroller full of buckets and cleaning materials, is the janitor. The lunch break offers relief. To Debussy’s Prélude à l’ après-midi d’un Faune, the three figures dart and play, evoking an illusion of a frolicsome faun wooing two enchanting nymphs. The dream ends; the women return to the monotony of the day.

Some fifteen years ago, Van Schayk began work on a series of paintings based on real or partially fictional moments in the life of Vaslav Nijinsky. The works, like the episodes related in Nijinsky’s diary, combine reality with fantasy. Nijinsky wrote his diary in 1919, taking just six and a half weeks to complete the work. The legendary artist, then in the early stages of mental instability, feverishly relates a chaos of thoughts and fears, identifying himself with nature and with God. Van Schayk first read the diary when he was eighteen.

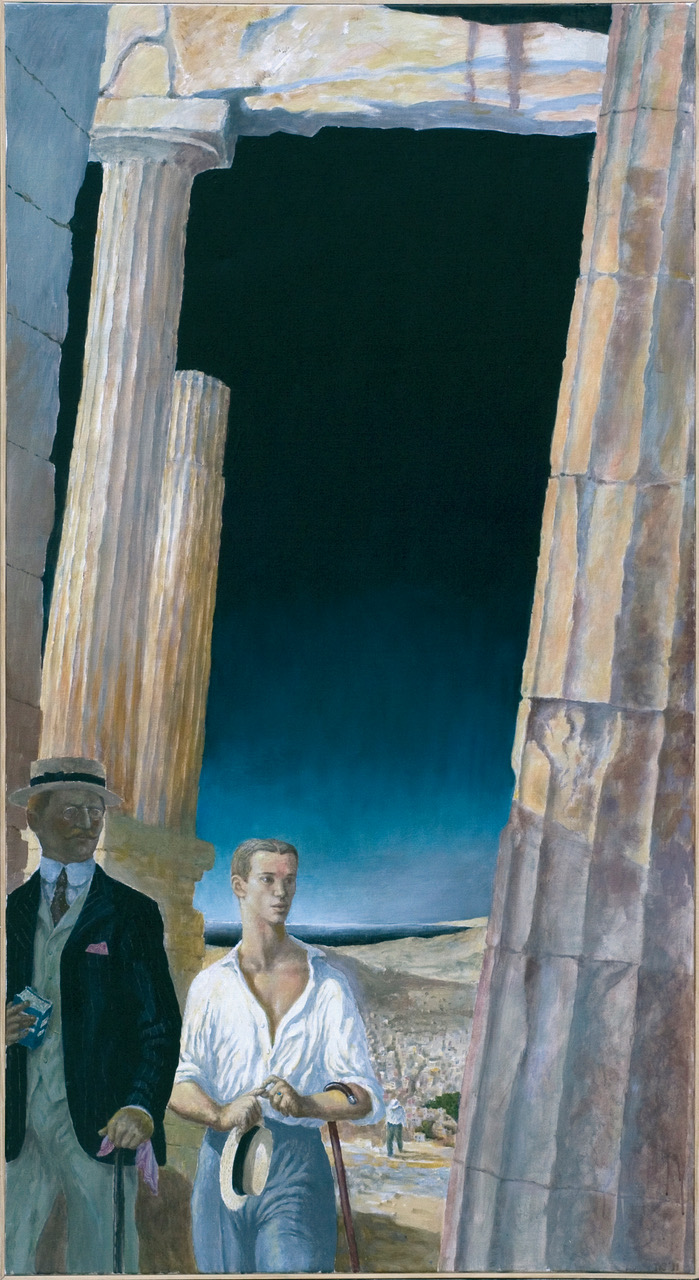

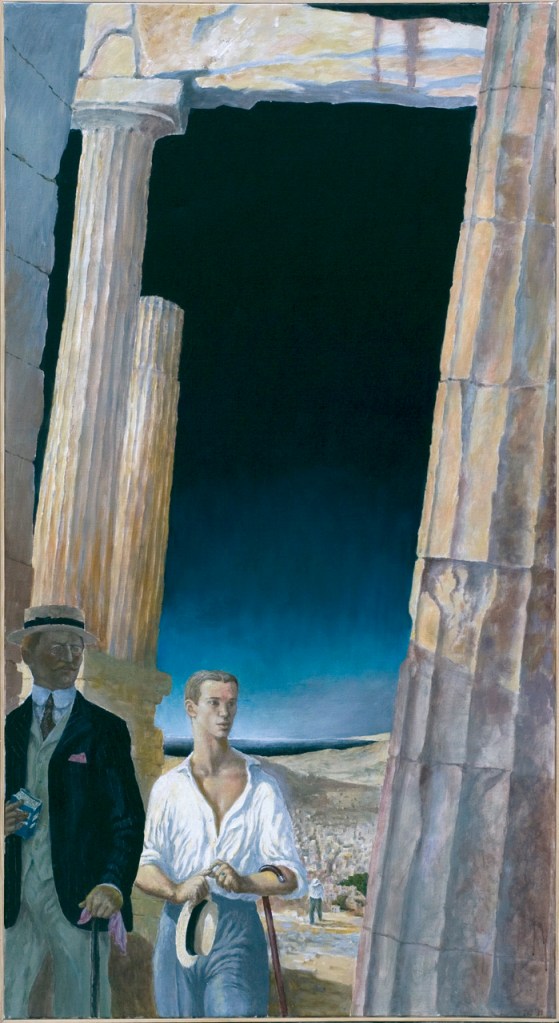

Bakst and Nijinsky at the Acropolis, Athens 1911, depicts a fictional scene. Bakst and Nijinsky were never present together at the Acropolis. Léon Bakst (1866-1924) travelled to Greece in 1907 alongside fellow artist Valentin Serov. An exquisite artwork, Terror Antiquus (1908), commemorates the journey. Bakst was an influential costume and set designer in the early years of the Ballets Russes and worked with Nijinsky on various ballets. He designed the costumes and sets for L’ Après- midi d’un Faune.

Bakst and Nijinsky at the Acropolis, Athens 1911 – acrylic paint on canvas

185cm x 100 cm – created in 2011

Photo Gertjan Evenhuis

Van Schayk portrays Bakst as a well-dressed gentleman and Nijinsky in a casual shirt with a wide-open collar. Bakst notably stands in the shadow, while Nijinsky catches all the sunlight. The high ancient columns tower above both men. In the background, the historic city of Athens is visible, with a deep blue Aegean Sea stretching behind it. The scene might be viewed as serene if not for the ominous dark blue sky.

The Proposal, Paris 1909 – oil/ acrylic paint on canvas – 95 cm x 90 cm – created in 2016

Photo Gertjan Evenhuis

The title The Proposal is uncanny. What is the essence of Diaghilev’s proposal? Van Schayk immediately directs the viewer to Diaghilev, who is clutching a bag of oranges in his left hand. His appearance is simultaneously awkward and potent. A pale, despondent Nijinsky is resting in a bed behind him.

The artwork is an adaptation of a situation recorded in Bronislava Nijinska’s biography.(1) Nijinsky also describes this moment in his diary. In 1909, Nijinsky contracted typhoid fever. Nijinska recalls that Diaghilev, who was anxious about contracting the disease, never set foot in Nijinsky’s room. He communicated with Nijinsky through the door opening. In his diary, which is by no means reliable, Nijinsky wrote that Diaghilev gave him oranges and “sat on his bed“. (2) Nijinsky continues to write that Diaghilev proposed they live together, promising to provide both financial and artistic support to his lover/protégé. Nijinsky, ill, scared, and lacking financial means, felt compelled to accept Diaghilev’s proposal.

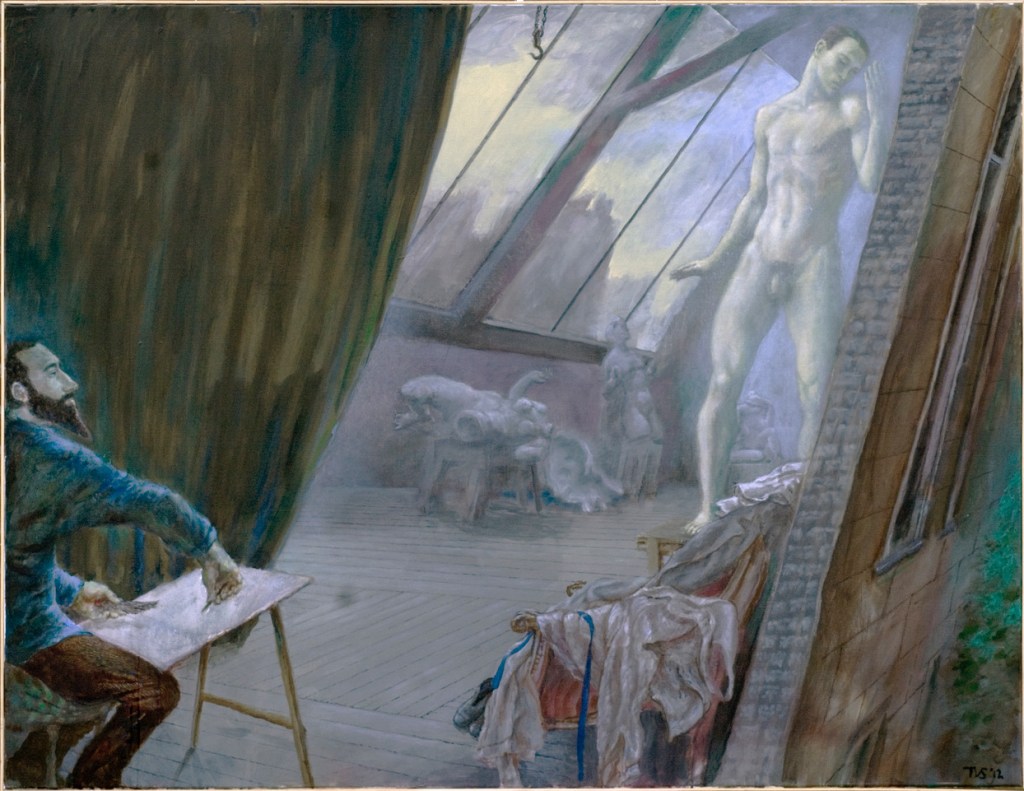

Where The Proposal has an uncomfortable, oppressive atmosphere, an earlier work, Nijinsky posing for Aristide Maillol, is more uplifting. Nijinsky was invited to pose for Maillol (1861-1944), a sculptor renowned for his female figures. Maillol, although deeming Nijinsky an ‘absolute Eros’, also found that Nijinsky ‘has no pectorals, enormous legs, and a wasp waist’. Though Maillol found Nijinsky ‘very beautiful’, his physique did not satisfy his aesthetic ideas. Maillol completed several drawings, but a proposed sculpture never came to fruition. (3)

Nijinsky posing for Aristide Maillol, Paris 1911 – acrylic paint on canvas – 155 cm x 120 cm

created in 2012 – photo Gertjan Evenhuis

Composition-wise, Nijinsky posing for Aristide Maillol is intriguing. The diagonal line plays a vital role. That the windows are tilted is understandable, yet how can the slanted wall be explained? There is also a distinct, ascending diagonal line between artist and model. The sculptor Maillol is cropped and tucked away in the lower left corner and looks up at his model. Nijinsky stands tall. There is barely enough space in the studio. His naked posture reaches from the floor to the ceiling. Nijinsky, in actual life, was not a tall man, but in this artwork, his elongated posture evokes the illusion of a Renaissance statue. The damaged and incomplete statues strewn across the floor are equally captivating. Has Van Schayk depicted a work in progress, or do the scattered statues foreshadow Nijinsky’s tragic path?

Toer van Schayk Left: Le Mariage avec Dieu, Sankt Moritz, 1919 – acrylic paint on canvas – 150 x 110 – 2012 Right: Der Weg gehüllt in Schnee, Sankt Moritz 1919 – oil paint 165 x 85 cm – 2016 photos – Gertjan Evenhuis

The two striking paintings displayed above are directly influenced by moments and thoughts captured by Nijinsky in his diary. Nijinsky repeatedly wrote that he loved Romola, but he was also apprehensive about her actions regarding his (mental) well-being. Romola and Nijinsky came from two different worlds. They had no common cultural heritage or shared language. Toer van Schayk wonders whether they ever understood each other. In his diary, Nijinsky writes that when riding in a carriage with his wife, he informs her that ‘today was the day of my marriage to God.’ Van Schayk depicts this bewildering moment. Romola, adorned in elegance with a lengthy pearl necklace, reaches out toward her elusive husband. Her attempt is in vain.(4)

Nijinsky’s own words best describe the last painting Der Weg gehüllt in Schnee, Sankt Moritz 1919.

I went out for a walk, once, toward evening. I was walking quickly uphill. I stopped on a mountain. It was not Sinai. I had gone far. I felt cold. I was suffering from cold. I felt that I had to kneel down. I knelt quickly. After that, I felt I had to put my hand on the snow. I was holding my hand down, and suddenly I felt pain. … I was frightened and wanted to run, but could not, because my knees were rooted to the snow. I began to weep.

The Diary of Vaslav Nijinsky Unexpurgated Edition, Edited by Joan Acocella pages 86-87

Vaslav Nijinsky, the ‘toast of Paris’, is depicted in paintings and sculptures by scores of artists. The majority of these artworks showcase Nijinsky, the dancer. He is almost always depicted in his iconic roles. Only a handful of artists have portrayed the man Nijinsky. Even fewer have depicted the man following his vibrant yet brief career. Toer van Schayk explores Nijinsky beyond the limelight, illustrating a magnificent dancer gradually distancing himself from reality. His larger-than-life portrait of the legendary dancer is unsettling. Nijinsky gazes inward. The pen held tightly in his right hand wrote his anguished words to the world.

(1) Bronislava Nijinska Early Memoirs – translated and edited by Irina Nijinska and Jean Rawlinson – pages 277-78 – f.p. 1981 – ISBN 0-571-11892-5

(2) The Diary of Vaslav Nijinsky Unexpurgated Edition – edited by Joan Acocella – pages 199 – ISBN 0-374-13921-0

(3)Éditions de la Maison des sciences de l’homme – Journal Comte Harry Kessler – entries 9, 10 and 11 August 1911. The text is in French. The translation is mine.

(4)The Diary of Vaslav Nijinsky Unexpurgated Edition – edited by Joan Acocella – page 7 – ISBN 0-374-13921-0

The Toer van Schayk website offers a wealth of information on the artist. There are many illustrations available under the headings Dance and Visual Arts.