An elegant minuet, staged in an idyllic garden, is not exactly what one would expect from a 19th-century Dutch artist. The celebrated artist Frederik Hendrik Kaemmerer (1839-1902), however, specialised in traditional French genre scenes. In 1865, Kaemmerer travelled to Paris to study with the distinguished French academic artist Jean-Léon Gérôme. In no time at all, Kaemmerer’s picturesque works became sought after.

The minuet was one of the most popular social dances at the court of Louis XIV. Kaemmerer’s artwork, nonetheless, does not present the Baroque era. The neoclassical structure in the background, constructed during the revival of the Greco-Roman ideals, and the women’s high-waisted, Empire-style gowns place the action in the late 18th century.

The Minuet – oil paint on canvas – 100.4 x 160 cm – date unknown but this specific style appeared from 1865 – RKD/ Netherlands Institute for Art History.

The dancers are situated directly in front of the impressive neoclassical columns. Surrounding them, other affluent ladies and gentlemen relax or engage in an amorous escapade. The dancers, the epitome of sophistication, have studied social dancing. They appear to have emerged directly from a ballroom. They are the embodiment of refinement and elegance. Notice how subtly the dancer’s torso is permitted to spiral and how the head delicately rotates over the shoulders. Likewise, the soft arch of the men’s backs underlines their gentility. The ladies are the essence of femininity. The graciousness with which they hold their gowns while offering their other hand delicately to their partner evokes the manner of court etiquette. Kaemmerer focuses on every minute detail, meticulously depicting, for instance, the floral embellishments on the ladies’ gowns and the flowers scattered on the ground.

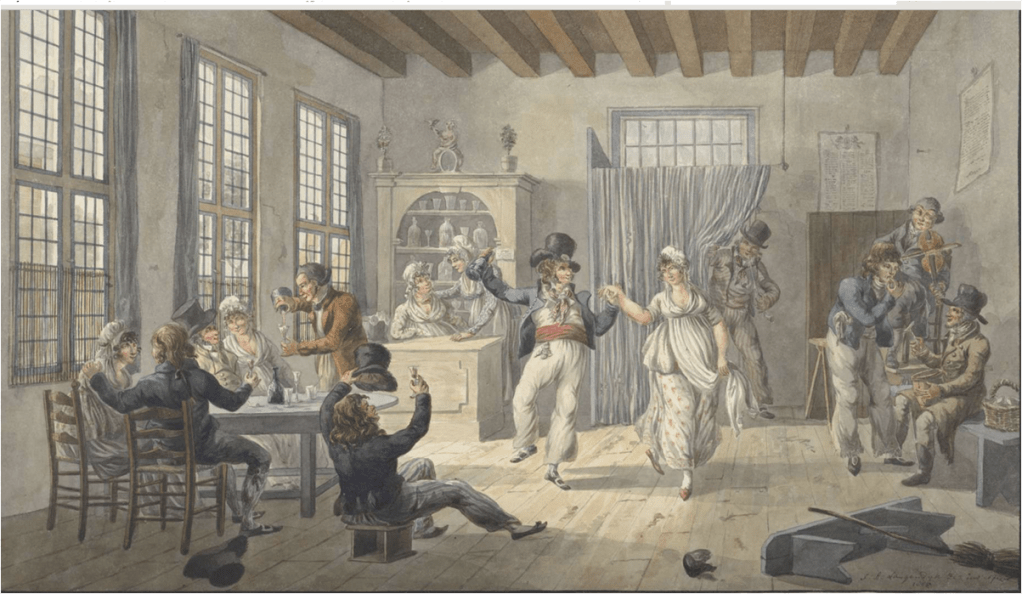

Cheerful company in an inn – Drawing: pencil & coloured brush – 215 mm x 318 mm – 1805 – Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

The tavern setting is synonymous with Dutch and Flemish art. The artists Jan Steen, Jan Miense Molenaer and Adriaen van Ostade, to mention just a few, created humorous, lively, serious, and dramatic tavern scenes. Cheerful company in an inn, a drawing by Jan Anthonie Langendijk (1780-1818) upholds the tradition. The artist has drawn a humble inn. This unsophisticated establishment is plainly furnished; there is a wooden table, a modest cupboard, and a simple curtain over the doorway.

Rays of sunlight passing through the window highlight the dancing couple. The man is nimble, no doubt fuelled by the ale he has consumed. The (empty?) bottle that is still in his hand possibly accounts for his tipsy expression. His lady partner performs identical movements but lacks the man’s vitality. Her nonchalance, the intimacy of the couples sitting at the table, the fallen bench, and the overly inquisitive man peeking around the curtain make me wonder just how ‘cheerful’ the inn actually is.

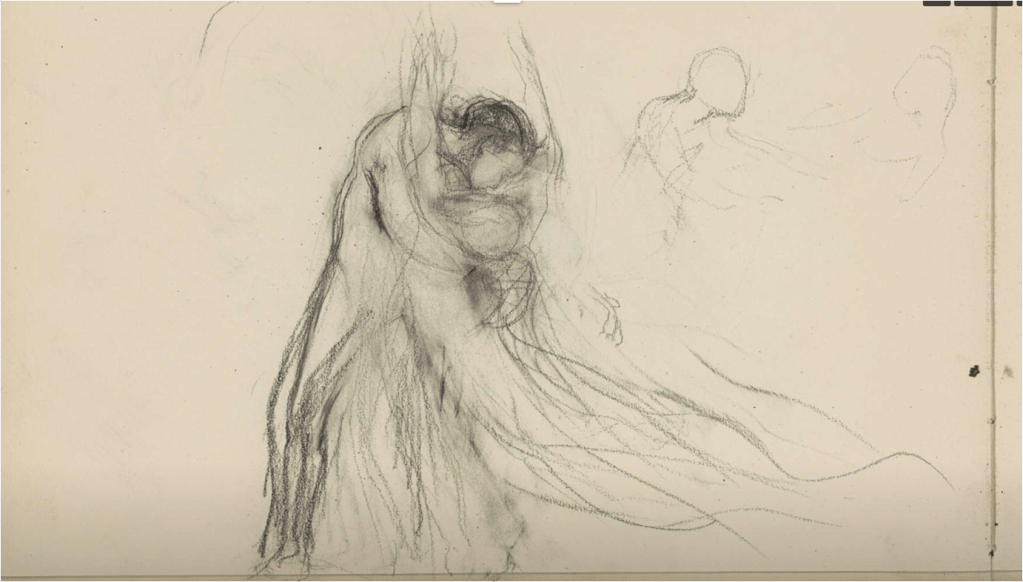

Embracing Dancing Couple – pencil on paper – 200 mm x 295 mm – page 46 from sketchbook – between 1865-1913 – Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

The name Bramine Hubrecht (1865-1913) may not be familiar, but this artist created an impressive range of landscapes, portraits, and genre scenes. Embracing Dancing Couple is a drawing from one of her sketchbooks and the only dance-related work I was able to find. The mood in this pencil sketch, similar to other works such as Torso of a Woman Crocheting, is tender, if not intimate. Hubrecht’s pencil strokes range from delicately fine to bolder lines. Occasional shading is added. The constant circular motion of her pencil conveys both movement and intense emotion. The embrace, beautifully rendered by the circular flow of the arms and head, is truly poetic. Even though this sketch belongs to the early 20th century, the dancer’s pose appears completely modern. The fervent embrace of the lovers would look perfectly natural in a contemporary pas de deux.

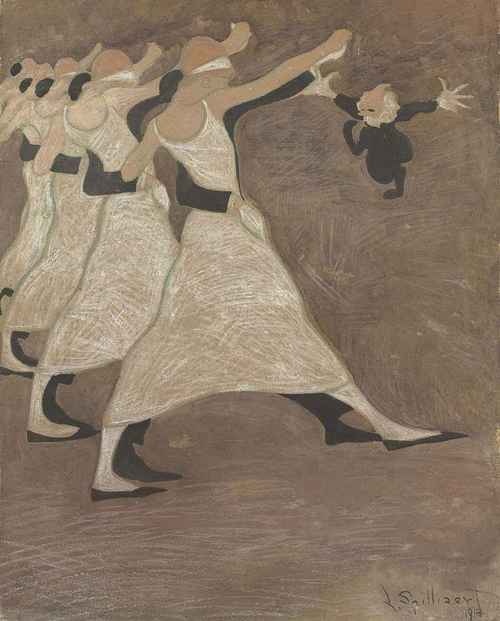

How to interpret a row of identical couples treading forward with vigorous strides in the direction of a short figure with open arms and one lifted leg? The tiny man, who could pass for a goblin, has extended his unusually large hands outward in an attempt to halt or warn the oncoming dance figures. The dancing figures occupy the greater half of the canvas. What dance are they performing? The extended arms, the tight embrace, and the dashing gait would suggest a tango.

Les Danseurs -pastel, chalk, brush and India ink and wash on board – 89.8 x 71.3 cm – 1913 – private collection – Christie’s

The artist, Léon Spilliaert (1881-1946), born in Oostende, draughtsman, lithographer and painter, was a unique artist. He was closely affiliated with the symbolist movement, inspired by and working with the playwright Maurice Maeterlinck. Spillaert created a large range of subjects often characterised by a very pronounced use of chiaroscuro with darkness as the ultimate factor.

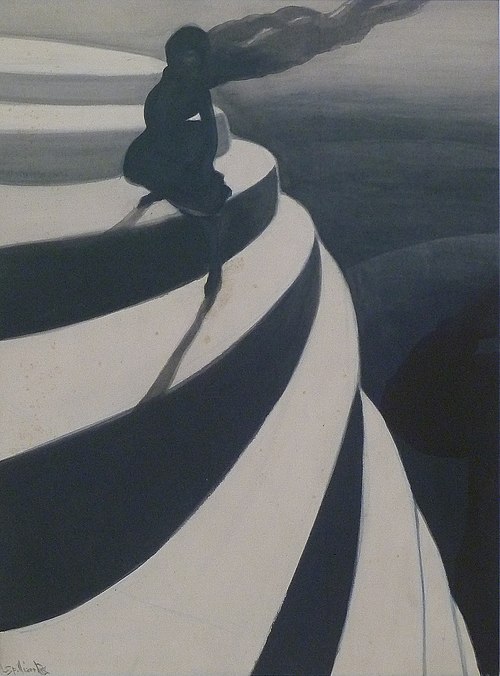

Léon Spilliaert – De Duizeling

(The Dizziness) 1908 – 92.32 x 69.43 – drawing – indian ink/coloured pencil on paper Mu.Zee, Oostende

This stunning artwork illustrates Spilliaert’s genius. While it may not be a dance image the solitary figure, with her hair ‘dancing’ in the wind, standing on a geometric structure, is undeniably an exceptional theatrical composition.

Han Mes (born 1936) drew her initial inspiration from mediaeval art. Starting in the 1970s, she created larger canvases, employing a more subdued and darker colour scheme. Her creations transformed from realistic to atmospheric. Eventually, she revisited colour and light, depicting figures within an undefinable space. The following painting, Two Dancing Figures, is presumably from that later period. To my knowledge, this is the only dance image in Mes’s oeuvre.

Two dancing figures – oil paint on canvas – 100 x 100 cm – between 1945 and 1999 – Kunstveiling, The Netherlands

Mes’s fascinating painting presents an ambiguous couple dancing a slow-paced dance; the dancers stand quite still. They support one another in a ballroom stance. The figures are little more than light skims, lacking any identifiable details. The artist applies paint in an almost abstract fashion. That one figure being shorter gives the impression that a man and woman are dancing.

The couple dances in an indistinct space. The walls, the floor, and the doorway are rendered in various hues of red. The oblique lines that define the red floor pull the observer toward the open door. The vertical lines of the different sections of the wall and the door create an indefinite height. These elements are sufficient to suggest a disquieting ambiance. However, Mes has introduced an additional element. The artist has placed an unusual shape in the long window that dissects the red walls. The observer can determine whether the vague form represents a reflection of the dancers or an unexpected visitor.

The Fauvist Kees van Dongen (1877-1968), celebrated for his bold paintings of dancers, prostitutes, and beautiful women, began work on Tango of the Archangel in the early 1920s. Some fifteen years later the artist presented his stunning painting.

Tango of the Archangel – oil on canvas – 196 cm x 197 cm – 1922-1935 – Musée National de Monaco

Tango of the Archangel is a powerful work. The dimensions — 196 cm x 197 cm — are impressive. Judging from a 1922 photograph taken in Van Dongen’s studio (Villa Said), the painting was intended to be displayed high on the wall, inviting the onlooker to look up. Quite understandable, seeing that woman and the archangel are larger than life. There are more notable aspects. The captivating woman is disrobed.* An impeccably attired figure wearing a black tuxedo rapturously embraces her. The figure’s face is hidden. The angel boasts a splendid wing that practically reaches from the top to the bottom of the canvas. The almost-nude woman, who wears only an embellished garter stocking, has slipped on a pair of distinct shoes. One shoe is orange with a green heel; the other shoe features contrasting colours. While this could be a style trend, the archangel’s black pumps are enigmatic. The dark angel wears identical high heels to the woman. Furthermore, the angel also wears black, sheer stockings.

The tango is passion, drama, and emotion. The overt sensuality and hypnotic musical rhythm of this sensual dance took Paris by storm early in the 20th century. Van Dongen was part of the Parisian elite. Van Dongen was also a talented dancer and undoubtedly performed his share of tangos. The two dancers in Tango of the Archangel are inseparable; their bodies are entangled in ecstasy. The setting, a background of curved forms in various hues of blue, heightens the ambiguity. Has the couple ascended into the clouds? Or is the background merely a metaphor to express the couple’s intense emotions? We could question if Van Dongen is being provocative. He dubiously suggests that the archangel may be female. Daring or playful, Tango of the Archangel is an ode to the decadence of the elite modern society in Van Dongen’s day.

* I have not forgotten that Manet also painted a nude figure in ‘Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe’. Manet’s nude, however, is an unexceptional woman in an exceptional situation. Van Dongen’s nude, in contrast, has absolutely no connection with the onlooker. Her manner and expression evoke memories of Saint Teresa in Bernini’s statue Ecstasy of Saint Teresa.