The previous post, Dutch artists captivated by Modern Dancers, highlighted artists inspired by modern expressionistic dancers. This post adopts a broader perspective, exploring unique images of dancers as depicted by Dutch artists during the first half of the 20th century. The featured artists employ diverse techniques, and the images range from figurative to near-abstraction. Join me in exploring a stunning collection of dance images that culminate in a rather tipsy dancing individual.

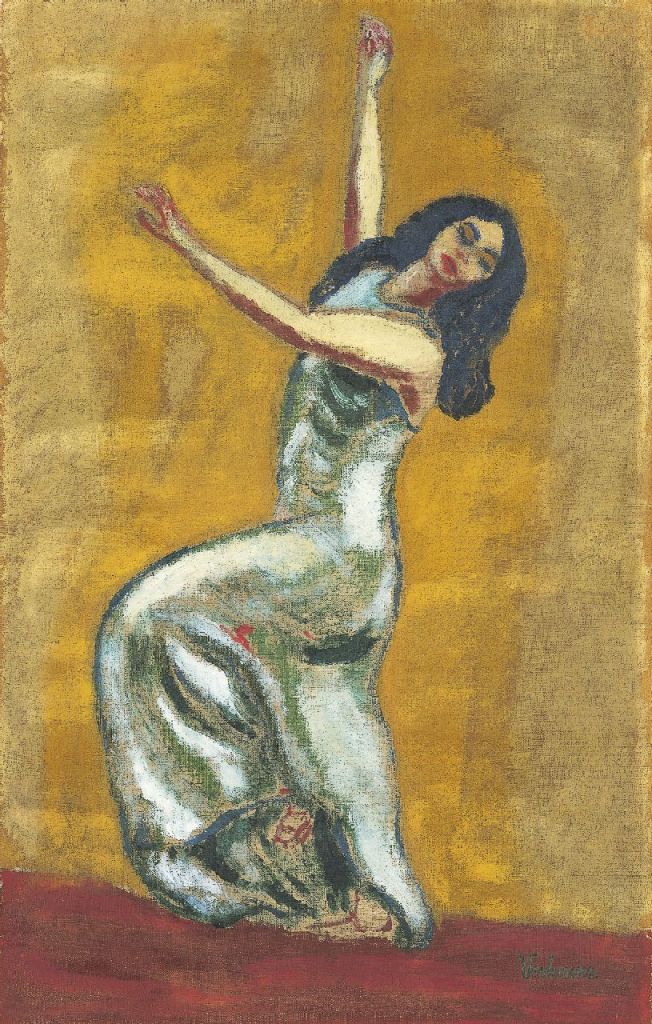

Let’s start with two works from the early 20th century. One work features a lyrical, natural dancer, and the other a geometrically stylised figure positioned in a traditional ballet pose. Danseuse, a painting by Jan Verhoeven (1870-1941), presents the lovely dancer caught in mid-movement. The dancer’s delicate lean backward, her flowing hair, and the gentle inclination of her head allow the onlooker to almost sense her next movement.

Danseuse – oil on canvas – 60.7 x 38.2 – 1910-1912 – Simonis & Buunk Kunsthandel, Ede The Netherlands

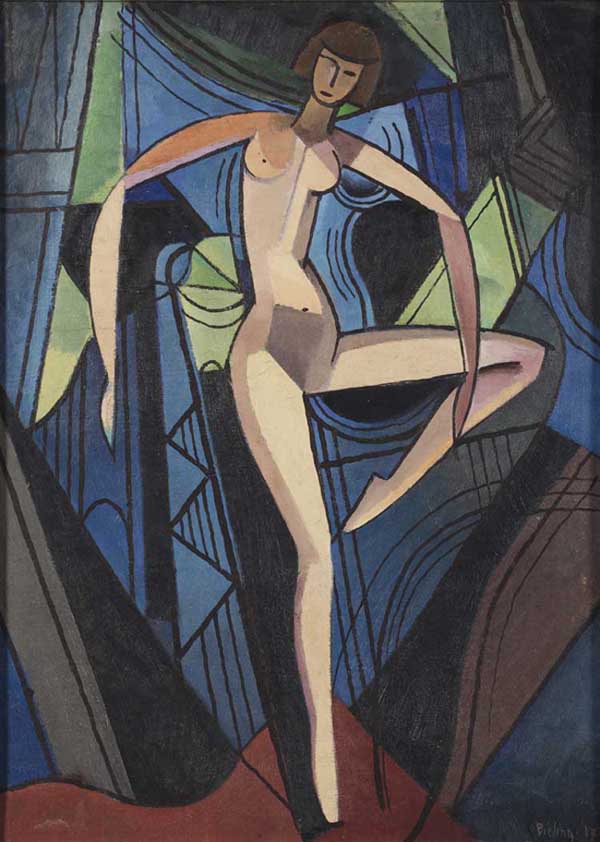

Right: Herman Bieling

A Dancing Nude – oil on canvas – 62 x 44.5 cm – 1917 – Invaluable and Christie’s

In A Dancing Nude, a work by Herman Bieling (1887-1964), the ballerina lacks realism. She is geometrically constructed; her outlines are shaped by bold curved or straight black lines. Note how her outer arm is depicted by curves that contrast with the straight lines of her inner arms. Her fair skin starkly contrasts with the dark backdrop, which, similar to the ballerina, is composed of triangles, rectangles, curves, and various two- and three-dimensional forms.

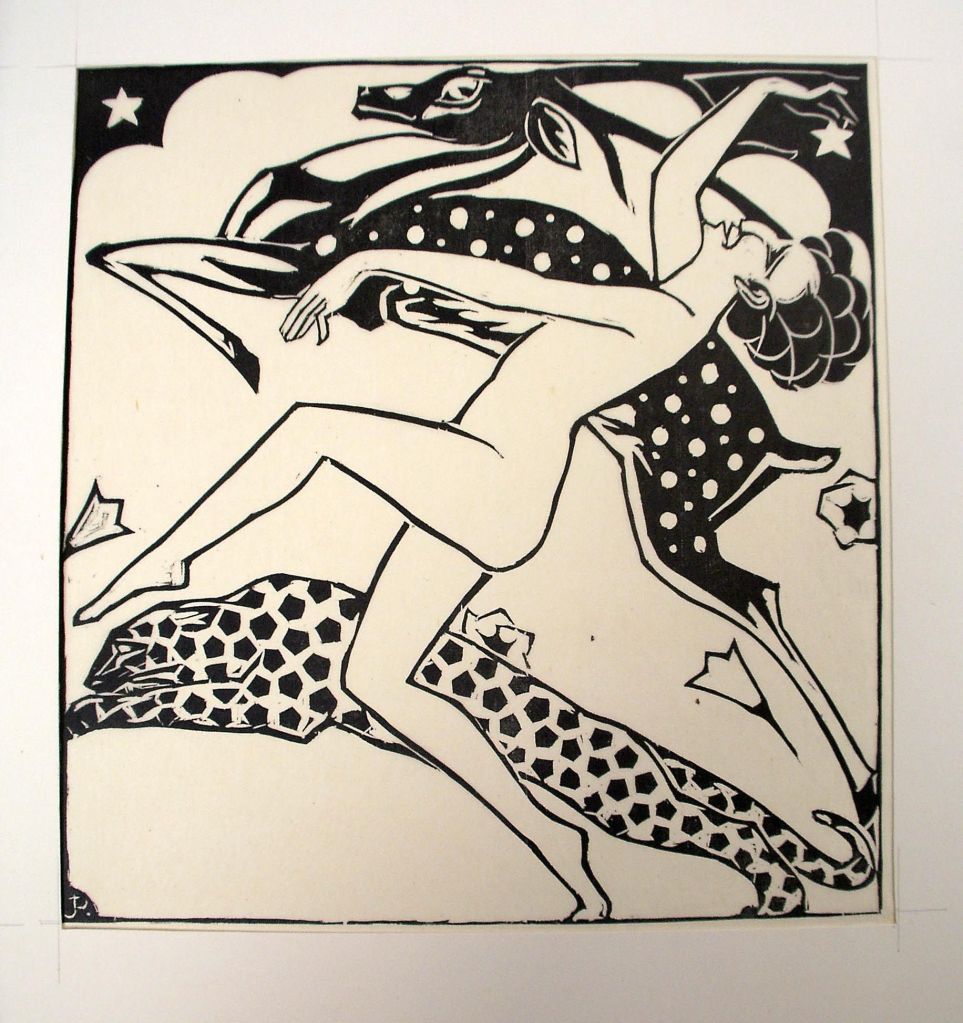

Johan Polet (1894-1971), a contemporary of Hildo Krop and Jan Rädeker, created the woodcut Dance for a Dutch periodical, Wendingen. The magazine was published from 1918 until 1933 and dealt specifically with contemporary architecture, art, and design. Each edition was devoted to a unique theme. The image illustrated below appeared in a 1919 edition that focussed exclusively on modernistic woodcutters.

Dance – woodcut on Japanese paper – 23 x 22 cm – Magazine Wendingen 1919 – Mr.F.J.Haffmans, Kunst en Antiekhandel, Utrecht

The title “Dance” offers no clues as to what is taking place in this unusual image. I see three reasonably realistically rendered figures juxtaposed in a totally unrealistic environment. The brisk antelope is an eye-catcher. Its elongated body reaches from the lower right corner and crosses diagonally over the page to the opposite side. It may be my imagination, but is the elegant creature gazing at the dancer? There is also a slender leopard poised, as if about to pounce. The dancer, the largest figure of the trio, echoes the historic images of German expressionistic dancers executing their gymnastic routines in the open air. The disrobed female figure raises one leg forward, rises high on her supporting foot, and pulls back forcefully into an energetic stance that challenges balance. It is odd, may I add, that the lively dancer’s hair remains so neatly in place.

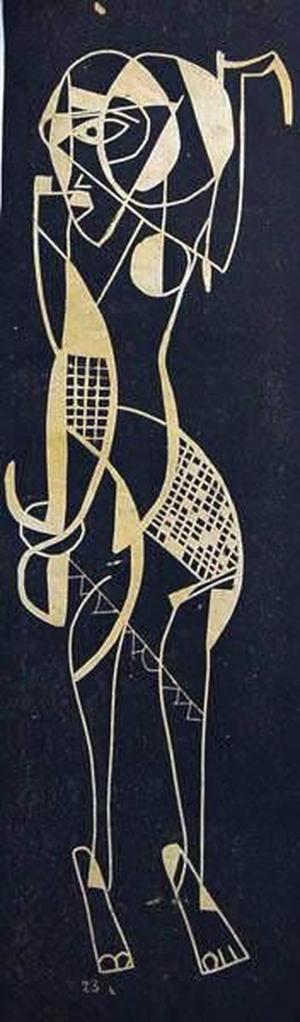

Pieter van Gelder – Dancer (Danseres) 46.6 x 12.8 cm – paper & silk cut lino – 1923 – Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem

Pieter van Gelder (1902-1984) was versatile. He was a graphic artist and painter, crafted ceramics, designed applied art, and produced puppets for shadow theatre productions. Van Gelder felt equally comfortable working with wood, rope, reeds, stoneware, or metal, drawing inspiration from exotic art styles and African artistry.

Dancer, the image displayed on the left, is merely one of the three closely related pieces in the Frans Hals Museum collection. The three pieces feature an identical elongated shape with roughly equivalent measurements. One artwork features the dancer in subdued green and pale orange hues against a dark background. In a second artwork, the dancer is illustrated as a white contour virtually submerged among grey and brown vertical lines, and finally, the current image displays the dancer completely represented in a striking white against the black surface.

African art, consider Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, captivated European art in the early 20th century. African characteristics—the elongated body, the distortion, the simplified shapes, and the mask-like face—are all evident in van Gelder’s work. In Dutch this artwork is titled Danseres, meaning, a female dancer. I personally find it quite a challenge to recognise the figure as female. Regardless, van Gelder’s command of geometric patterns—curves, lines, textures, and shapes—is as striking as it is intriguing.

Willem van Konijnenburg (1868-1943) was, like Piet Mondrian, an avid dancer. According to fellow artist Chris de Moor, Van Konijnenburg could dance the tango for hours on end. He, together with Jan Toorop, Leo Gestel, and Jan Sluijters, was one of the most prominent Dutch artists during the interbellum period. Early in his career, the artist created landscapes and portraits while also earning a living through book decorations, illustrations, and murals. Beginning around 1900, van Konijnenburg developed a fascination with Renaissance and Egyptian art, as well as symbolism, an art style embraced by his contemporaries Toorop and Johan Thorn Prikker. His symbolic works are highly innovative, based on a unique and personal geometric style established on mathematical principles.

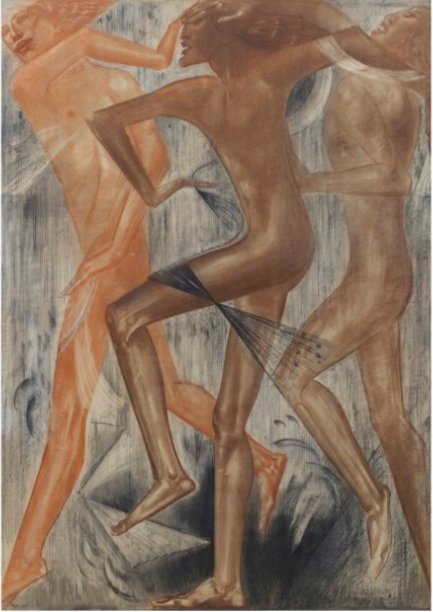

Between 1917 and 1919, van Konijnenburg created a collection of six drawings. Each drawing, representing a different dance style symbolises traits of the human condition: youth, conflict, fear, destiny, and other universal concepts. The artworks, of nearly identical size, are drawn on paper using crayon or charcoal. One main figure dominates each drawing. The figure’s head or hairline is often cropped. Van Konijnenburg selects his colours meticulously. The War Dance is confined to a metal/gold hue juxtaposed against a heavenly blue. For the Witch Dance and the Dance of Fate, the artist restricts himself to brown and yellow. In the Dance of Youth, shown above, black lines and marks accentuate the subtle use of a yellowish-brown.

Dans der Jonkheid (Dance of Youth) – 122 x 87 cm – black & coloured crayon on paper – 1917 – Artnet

Rituele Dans (Ritual Dance) 122 x 87.5 cm black and coloured charcoal on paper – 1918 – Christie’s/Artnet

Van Konijnenburg’s profound sense of movement is common to all the drawings. Being an accomplished tango dancer, the artist fully understood body language and the intricacy of dance. The elegantly poised dancers in Dance of Youth are statuesque. I could envision them as a relief on an Egyptian temple. Yet, even though they are composed, they are not stationary. The dancer’s intense gaze paired with a graceful stepping action effectively implies momentum. The movement is even bolder in Ritual Dance. Reminiscent of ancient art, the front dancer is positioned in profile with the upper body rotated to the front. Her forceful arm and leg movements, with her prominently protruding chin, are ceremonial and highly exotic. Her companion, to the right, performs in a ritualistic trance. The nude to the left is distinctive. Her body language evokes visions of Salomé in Herod’s Banquet, a masterpiece by Domenico Ghirlandaio (1486 and 1490). Was this Renaissance artwork a source of inspiration for van Konijnenburg?

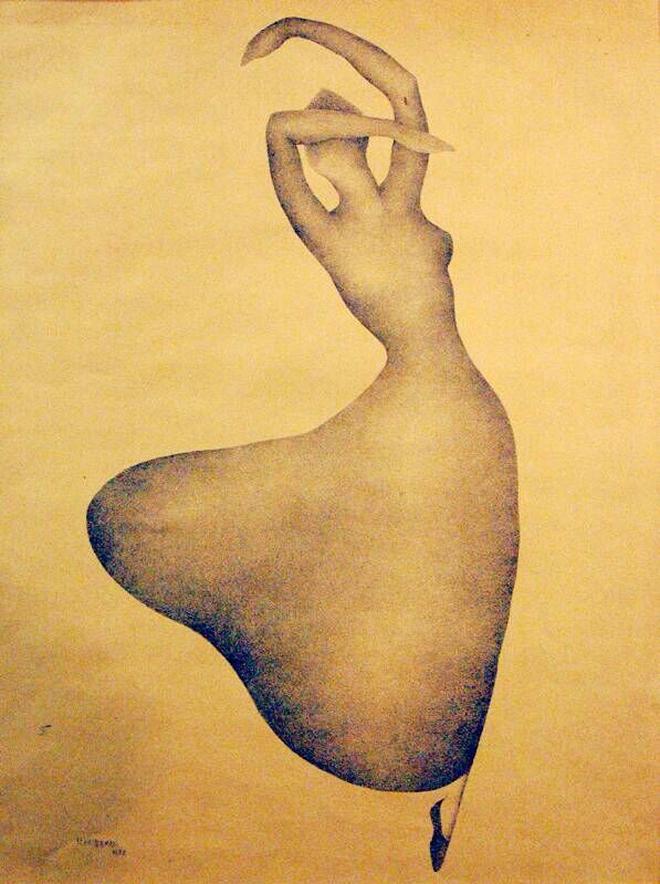

The distinct contours, the angular elbows, and the sharply flexed wrists observed in the above works, which are so characteristic of van Konijnenburg’s style, starkly contrast with the two dance images presented below. Danseres (Dancer) is an early work by Nola Hatterman (1899-1984) and, to my knowledge, her only work that highlights a ballet-like dancer. However, jazz music and popular dance were recurring themes in her work.

Dolf Henkes (1903-1989), the artist of Pavane, lived and worked in Rotterdam. Henkes was a diverse artist. He painted harbour scenes, the countryside, portraits, and numerous works featuring circus and theatrical performances. His painting Pavane is an early work. A pavane is a slow, dignified historical dance. This led me to wonder how the painting was related to a 16th/17th-century dance. Only then did I realise that the German choreographer, Kurt Jooss, created a magnificent dance work titled Pavane in 1929. Images of that choreography, set to Maurice Ravel’s Pavane pour une infante défunte, show the protagonist wearing a comparable costume and adopting similar body language as illustrated in Henkes’ painting.

Danseres – paper, ink litho – 56 x 43 cm – 1932 – Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem.

Dolf Henkes

Pavane – oil on canvas – 150 x 100 cm – 1932 – Stichting Dolf Henkes

Hatterman’s lyrical figure is suspended in mid-air, floating in a monochrome void. Her only connection to gravity is a downward-pointed foot. The gentle shading and the absence of facial features suggest a sense of ephemerality. While Hatterman’s figure is an apparition, Henke’s dancer appears to be realistic. However, on closer inspection of her slender, twig-like fingers and inquisitive expression, an air of mystery emerges.**

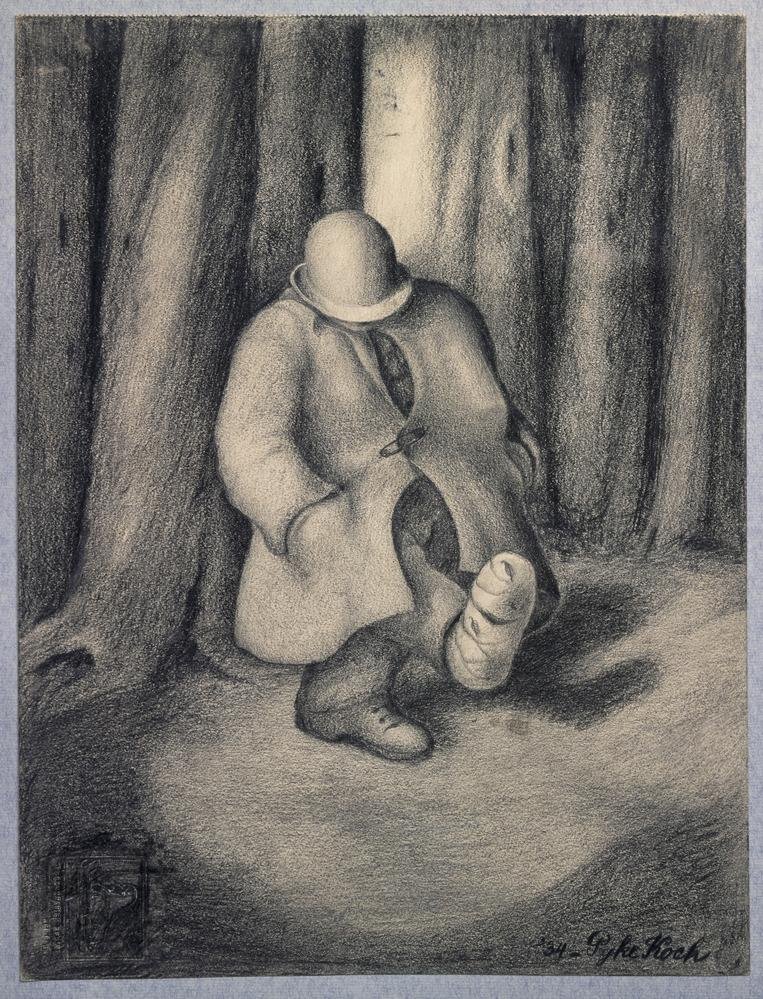

And finally, the promised image of an inebriated dancing figure. I saw this small drawing at an extraordinary exhibition dedicated to Pyke Koch. I was amazed at the delicacy of this meticulous drawing. Koch is an autodidact. He is famed for his magical realist works. His paintings are austere, featuring realistic characters finding themselves in bizarre and puzzling surroundings. The Dancing Drunk (1934) is an early work highlighting an unremarkable, anonymous figure, clad in a sloppy coat, donning a bowler hat that entirely obscures the face; a group of tall tree trunks clustered closely together are the sole companions.

Dansende Dronkaard (Dancing Drunk) – pencil on paper – 35.5 x 27 cm – 1943 – Collectie Centraal Museum Utrecht – foto Ernst Moritz © Pictoright.

My admiration for this modest artwork is twofold. This monochromatic pencil drawing is full of surprises. I was captivated by the unexpected variety of textures and skilful interplay of light and shadow. The shading of the tree trunks, for example, is fastidious, as are the shoes, coat, and the individual’s bandaged foot. Furthermore, this unpretentious drawing evokes empathy, raising unanswerable questions. Why is the figure’s foot bandaged? Why is this nonchalant individual dancing in total solitude? And how can this pensive figure be both forlorn and humorous at the same time?

The dance, in the words of the eminent art historian Walter Sorell, has many faces. This post presents a few of those faces. Every piece of art raises questions and frequently serves as food for thought. Pyke Koch provided an approach that was both straightforward and effective.

A painting is a self-service store. Everyone takes what suits them.*

Pyke Koch

*’Een schilderij is een zelf-bedieningwinkel. Iedereen haalt er uit wat hem van pas komt” – Leidse Dagblad 17July 1991.

This quotation presents the closing remarks of an article written by Hans Lutz. The article ¨De eeuwige raadsels van Pyke Koch” covered the exhibition “Souvenir d’un Songe”, celebrating Koch’s 90th birthday. The English translation is mine.

** I must point out that there is a smaller, comparable painting, also titled Pavane, with an almost identical dancer. The colour palette resembles the larger painting. However, the deeper hues accentuate an even intenser atmosphere. The dancer’s expression is grotesque.