At the dawn of the 20th century, dancers Isadora Duncan and Loie Fuller, along with modern dance pioneer and theorist Rudolf von Laban, unveiled a groundbreaking style of dance. These artists aimed for a freedom of movement previously unseen in ballet. The performers acknowledged gravity, explored spatial design, and adopted a natural flow of movement. Modern dancers, like revolutionary artists and composers, sought to express, to quote Kandinsky, their “inner necessity”.

In April 1905, the trailblazing American dancer Isadora Duncan made her debut in Amsterdam. In the following years, she returned to perform widely across the Netherlands. Loie Fuller toured Belgium and Germany. Lili Green acted and danced on many Dutch stages. She and fellow dancer and teacher Jacoba van der Plas paved the way for future dance generations. The dance performances of the Polish/German dancer and choreographer Gertrud Leitsikow were received with great enthusiasm. These dancers captivated visual artists. Jan Sluijters, Ernst Leijden, Harmen Meurs, Mommie Schwarz, Hildo Krop, and Theo Vos were among the Dutch artists inspired by expressionistic dance.

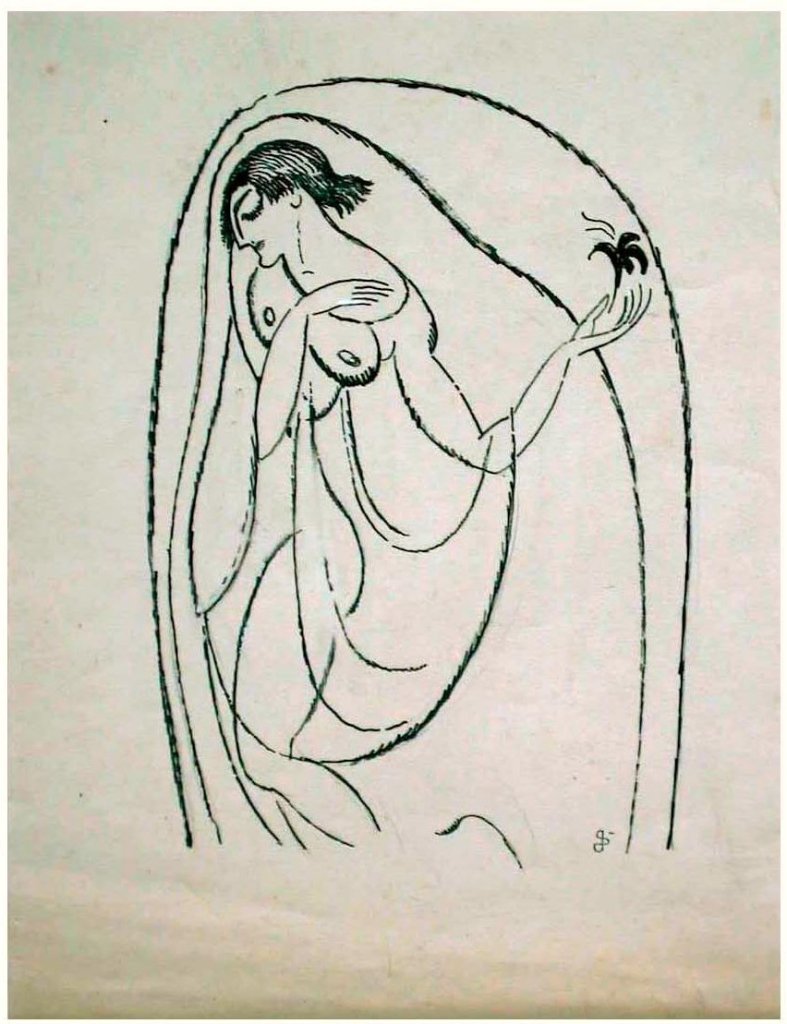

The dancer Gertrud Leistikow- paper, ink – 235 mm x 175 mm – c. 1918 – RKD, Netherlands Institute for Art History, The Hague

Theo Vos

Gertrud Leistikow – porcelain sculpture – height 12 cm – executed by Hutschenreuther, Germany ca.1925

Harmen Meurs

Gertrud Leistikow – 1919 – 50 x 32.5 cm – from Portfolio Gertrud Leitsikow 10 dans schetsen – Collection Drs. Marius Sterrenburg Kunsthandel

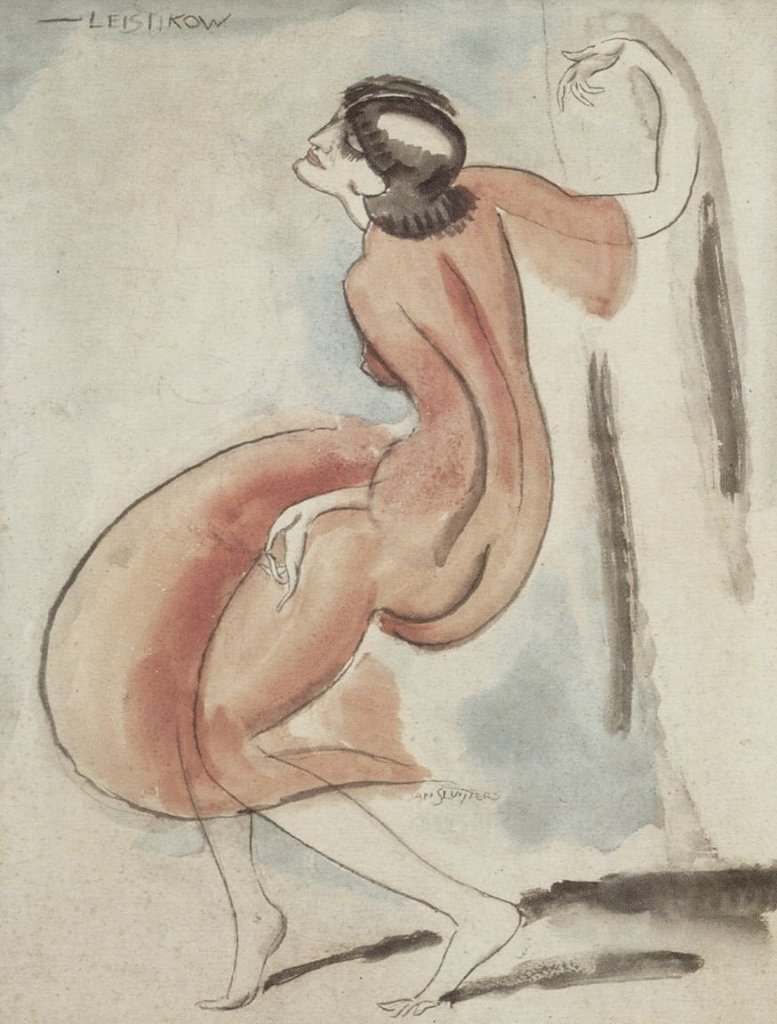

The dance images by Jan Sluijters (1881-1957), ranging from Bal Tabarin to Spanish dancers to exotic dancers, are stunning. Sluijters was also fascinated by Gertrud Leistikow, creating dance portraits and images based on her extraordinarily expressive dance style. He highlights, in both artworks presented here, Leistikow’s intense expressivity and her sensual curves. Her elegance, her eloquence, and her artistry illuminate his art. Sluijters and his peer Ernst Leyden (1892-1969) both present Leistikow as a charming, if not mesmerising, woman. Nevertheless, Leyden adopts a slightly different approach. While Sluijters emphasises dance in addition to femininity, Leyden’s artwork highlights the provocative, alluring Leistikow. She is virtually disrobed, save for a long translucent cape and a skirt conveniently draped to expose the front of her body. Her pose is motionless. Only hand gestures and her yearning gaze indicate her unmistakable theatricality.

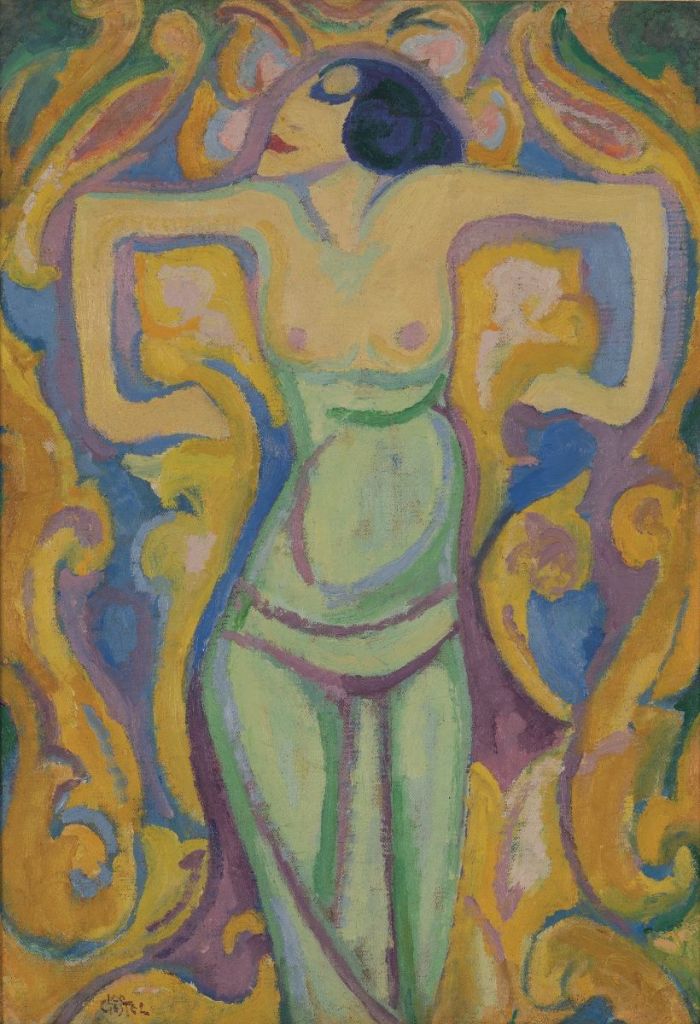

Jan Sluijters

The dancer Gertrud Leistikow 400 mm x 310 mm – paper, watercolour and pen – c.1920 – RKD, Netherlands Institute for Art History, The Hague

Ernst Leyden

Gertrud Leistikow – 97 cm x 61 cm – pencil & watercolours – 1919 – private collection – Issuu.

Below

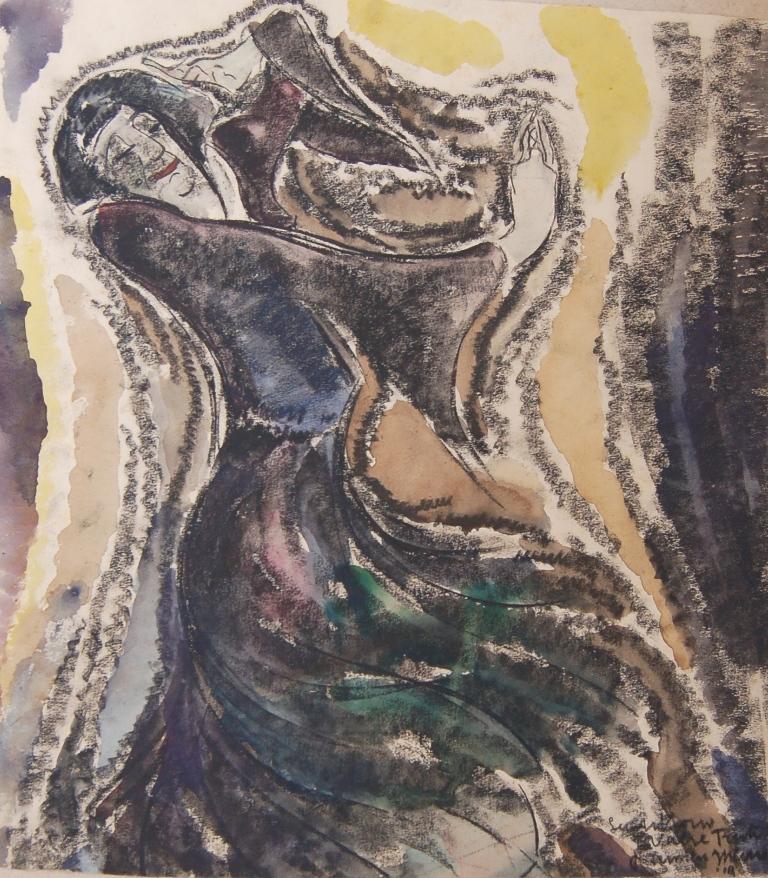

Harmen Meurs

Gertrud Leistikow -charcoal and watercolour on paper – 50 cm x 32.5 – 1919

Two works from Portfolio Gertrud Leitsikow. (Portfolio 10 Dans Schetsen) Collection Drs. Marius Sterrenburg Kunsthandel

The graceful lines and sensuality prominently featured by Sluijters and Leyden are absent in a collection of ten works of Gertrud Leistikow created by Harmen Meurs (1871-1964). Every scene, rendered in watercolour and charcoal, showcases Leistikow in one of her signature pieces. Meurs was no stranger to dance. His rendition of a dancing Salomé is striking, as is a vibrant portrayal of an early Dutch expressionist dancer, Florrie Rodrigo.

Regardless of whether Meurs selects a blue and mauve palette or a darker colour design, the dancer Leistikow is depicted in dynamic motion. She leaps, weaves, spins, and is constantly moving. The artist employs charcoal to sketch the contours of the performer in swirling, continuous strokes and lines. The dancing figure is further embedded in a flurry of indistinguishable space, rendered in rough, uneven strokes. Meurs, also acclaimed for his precise and detailed portraits, landscapes, and village scenes, appears to work swiftly in the Leistikow series. Perhaps he depicted the dancer in action.

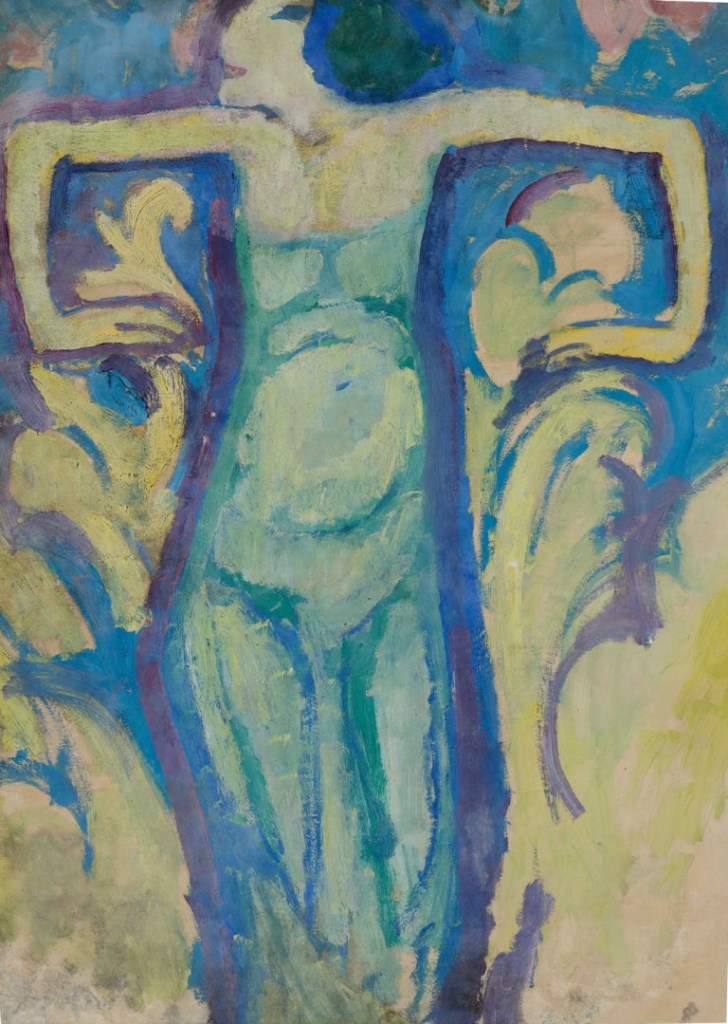

Leo Gestel (1881-1941), a friend of Jan Sluijters, was an esteemed avant-garde artist. During his third trip to Paris, around 1911, he encountered Fauvism. He promptly explored bold colours and discarded the conventional perspective. One of his earliest Fauvist ventures was Danse Orientale, a work often regarded as being inspired by the expressionistic performer Lili Green. The colours of this innovative work are vibrant, and perspective has given way to a flat pictorial style. Gestel made three interpretations: a small preparatory work, an oil painting, and one that was destroyed in a fire in 1929. The dancer is not rendered realistically. There is no need for me to detail the anatomical improbability of the dancer’s slender, contorted arm movements.

Left: Danse Orientale – oil and mixed media on paper 547 mm x 38 mm – c. 1911 – Perspective Fine Art, Vienna and Amsterdam

Right: Danse Orientale – oil paint op doek – 53 x 37 cm – oil on canvas – c. 1912 – private collection – Exhibited Singer Museum, Laren (Netherlands)

The palette of the preparatory work is defined by an atypical combination of blue, green, and yellow. The colours are even bolder in the larger, 1912, version. Aside from her arms and torso, this female figure is predominantly rendered in green and further adorned with curved mauve lines. She is engulfed by swirls and floral-like patterns in various hues of yellow and brown intermingled with blue and mauve. Such a combination of colours may surprise no one today, but in 1912, when society was emerging from Victorian propriety, it was truly remarkable. This surge of ravishingly novel colours owes much to the Ballets Russes. Diaghilev’s renowned company captivated Paris. The 1910 production of Scheherazade, a ballet created by Michael Fokine, was overwhelming. Leon Bakst’s unique costume designs and stage sets sparked the emergence of exoticism. Fashion (Paul Poiret), furniture, jewellery, perfumes, theatre, dance, and art were all enraptured by this new rage. Oriental dancing was in vogue. The exotic, sensual performer Mata Hari, who doubled as a spy, comes to mind.

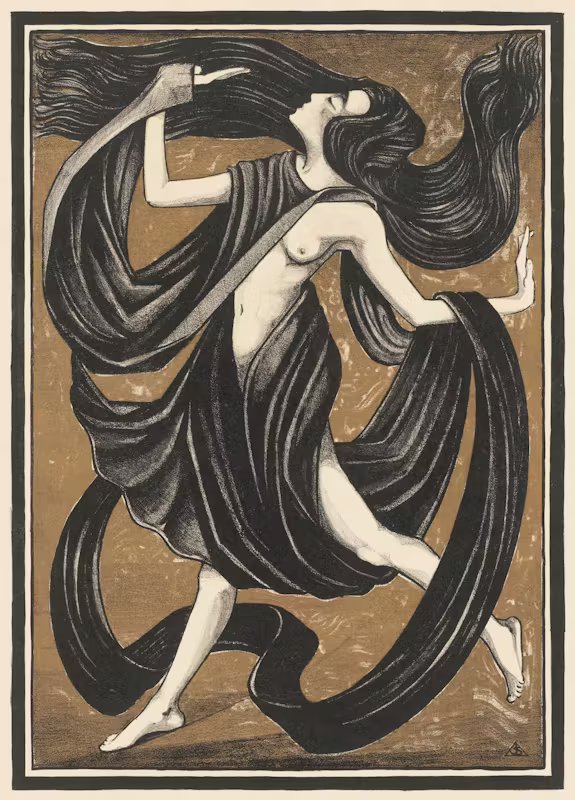

The vivid colours in Oriental Dancer are breathtaking, if not crucial to Gestel’s work. However, his contemporary, Henk Schilling (1893-1942), opted to depict an expressive dancer using only a ‘basic’ palette of black, brown, and beige. The more mature, established artist Jan Toorop (1858-1928) also limited himself to earth tones. Schilling was a graphic artist, painter, and above all, a master glazier. His wonderful window designs adorn churches and buildings throughout the Netherlands. Toorop, an eminent artist, holds comparable significance to Van Gogh and Mondrian.

Dream Dancer (Danseres met draperieën) – lithograph in black & gold – 458 mm x 333 mm – 1919 – Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam – Public Domain Image Archive

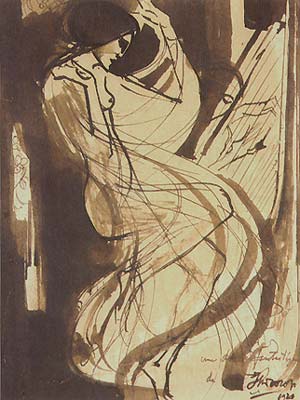

Jan Toorop

Une Danse Fantastique – Pen and ink – 13,5 cm x 10.8 cm 1920 – ARTNET

Schilling’s dancer is adorned with a long graceful scarf that, apart from one bare breast, covers her body at all the appropriate places. The hovering fabric is symmetrically draped around the dancer, creating an illusion of equilibrium, an effect enhanced by her flowing hair that extends beyond the edges of the lithograph.

The dance figure portrayed in the Toorop sketch is pensive and yields to gravity. Her curved demeanour, the contracted torso, and her introverted manner evoke the expressive gestures characteristic of German Ausdruckstanz. The photo (left) shows Mary Wigman, one of the greatest exponents of Ausdruckstanz. It provides a glimpse of the dance that may have inspired the artist.

Mary Wigman – photographer Hanns Holdt – c. 1914 – Deutsche Theatermuseum, Munich

These two works invite comparisons. The resemblances are evident. The colour palette is comparable. The dancing figures nearly fill the entire space, and both are minimally clad. The dancer portrayed in Schilling’s artwork is fairly realistic. Toorop’s dancer is an enigmatic sketch. Both artists employ sweeping and flowing lines, yet they do so in completely different ways. Schilling lines are distinctly defined, calculated, and unambiguous. In comparison, Toorop effortlessly flows with pen and ink, shifting from one curve to the next. Nevertheless, a fundamental distinction exists. The expressionist dance, as expressionism in music and art, emerges from a powerful internal motivation. In Schilling’s work the dancer, though sprightly and gracious, lacks the intense emotion characteristic of expressionistic dance. In reality, the piece has an ornamental quality. In contrast, Toorop’s dancer is earthbound. She is neither graceful nor alluring. Une Danse Fantastique reflects the vital essence of inner necessity pursued by the contemporary expressionist dancer.

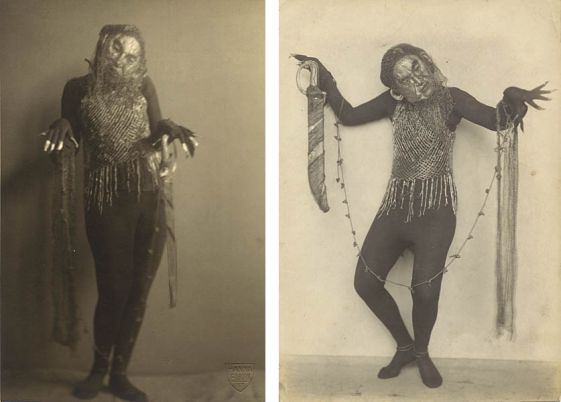

In concluding this introduction regarding the relationship between Dutch artists and contemporary dancers, I want to highlight the sculptor Hildo Krop (1884-1970). Krop’s work is paramount in Amsterdam. If you were to take a leisurely stroll around the city, you would likely come across his distinct sculptures on bridges, buildings, homes, and in public spaces. This prolific artist, formerly the designated sculptor for Amsterdam, also crafted furniture, glass, and ceramics, and produced remarkable masks for theatrical performances and for Gertrud Leistikow. Two exceptional artists – Leistikow and Krop – whose synergy motivated both to achieve even greater accomplishments.

The left photo shows Gertrud Leistikow wearing an African mask created by Hildo Krop. (c.1921 – Allard Pierson Museum, Amsterdam). On the right there are three masks by Hildo Krop. All the masks are made of papier-mâché. This photo was taken during an exhibition devoted to Gertrud Leitsikov in the Museum Kranenburg (2014). Directly above the masks there are four artworks by Harmen Meurs, some of which I discussed above. I found the photo on the blog Il faut voyager. The centre mask was used in Groteske (1926) and the mask on the right-hand side for the Fanatieke dans /Fanatical dance (1922).

Right: Hildo Krop – Mask for Goldene Maske for Gertrud Leistikow – 1918 – photo, with thanks, from Il faut voyager BLOG