The art collective CoBrA was established shortly after WWII. An international group of artists founded a collaborative network that extended throughout northern Europe. The Dutch, Belgian, and Danish artists challenged traditional art movements and rejected bourgeois art, finding inspiration in Paul Klee, Joan Miró, artworks by children, outsider art, naïve art, and primitive artistic expressions. Although dance and dancers were not a major focus, these creative artists produced bizarre, thought-provoking, and striking dance images. These works, while neither abstract nor non-figurative, do not represent your conventional dance imagery. In every instance, however, their titles allude to dance. Appreciate the ways four remarkable artists — Jan Nieuwenhuijs, Anton Rooskens, Theo Wolvecamp, and the poet-artist Lucebert — depicted dance.

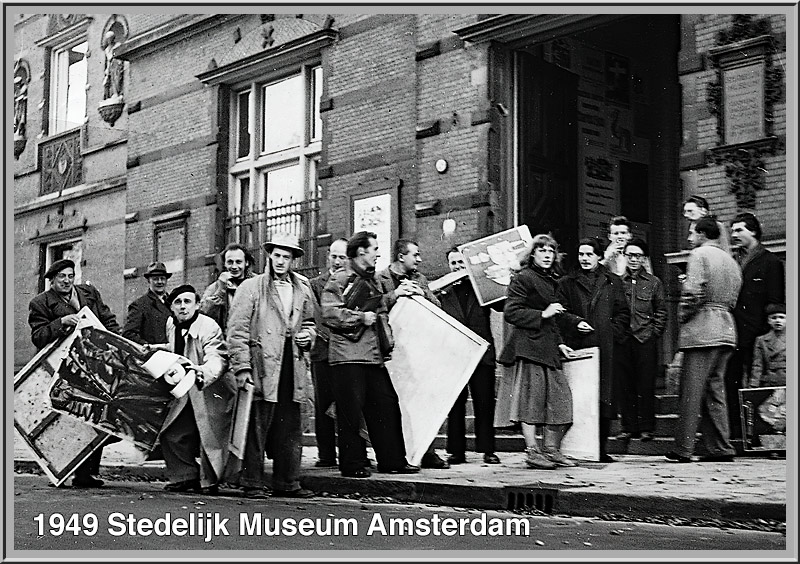

F.l.t.r.: Anton Rooskens, a passer-by, Bert Schierbeek ,Theo Wolvecamp, Eugène Brands, Karl Otto Götz, Corneille, Jacques Doucet, Alechinsky Tony Sluyter (girlfriend of Karel Appel), Lucebert, Jan Elburg, Shinkichi Tajiri, Gerrit Kouwenaar, Constant, Karel Appel and Constant’s son Victor

Jan Nieuwenhuijs (1922-1986), brother of Constant, was one of the founder members of CoBrA. His work is figurative. Animals, cats, birds and fantastic creatures inhabit his canvases. These are assembled of human, animal and mechanical elements.

Dancer – 1951 – painting – no dimensions given – I paint the way I laugh; website Jan Nieuwenhuijs

Dancer screams for attention. Indiscernible figures and objects lurk amid a splash of colour. Colour, form, line, and patterns dance freely over the canvas. Mysterious eyes haunt the image. A motley of red hues pounces off the canvas, revealing a tall, slender woman. The statuesque figure is motionless. Her torso, boasting two enormous breasts, is exceptionally wide, creating a dynamic contrast with her narrow waist. Her face, characterised by two distinct tones, is embellished with a diadem of sparkling gems. She resembles a mythological figure. This mystic being is further adorned with asymmetrical designs of lines, circles, and dots. Nieuwenhuijs employs a bold black stripe to define the contours of her body. Analogous dark lines illustrate a mysterious form situated across the canvas, partially hidden by a wheel mounted on a high pole. What is the connection between these items and the female figure? The title Dancer provides little clarity.

The Dance – oil on canvas – 62 cm x 86 cm – 1951 – Artnet

The dark lines define the forms of two dancers. The legs of the left figure are constructed similarly to a doll, having adjustable limbs fastened with clips. The dancing couple face each other, their torsos slightly leaning back with one leg raised. However, it’s not the dancing that draws attention. Instead, it is the mishmash of colours spread unevenly across the canvas. A closer look at the figures uncovers the disturbing sphere that lingers in The Dance. A skull is embedded in the abdomen of the right figure, who is, coincidentally, quite unsettling himself. This enigmatic image is filled with uncertain components, the most mysterious being the tiny visage of an elderly man located near the top of the canvas between the dancers.

Anton Rooskens (1906-1976) was a self-taught artist. His initial inspiration came from the expressionist works of Vincent van Gogh. Post-1945, inspired by folk art from Africa, India, and New Guinea, his creations became increasingly experimental, emphasising vibrant colours and shapes.

My art is an expression. I improvise. I do not know what my painting will end up as when I begin. You start painting. And you discover. That’s CoBrA. What you see in my paintings has all been discovered”.

(Anton Rooskens quoted from Virtus Schade: “Afrikas Magi” (The Magic of Africa), Copenhagen 1971, p. 11

Rooskens presented Danse Macabre at the gloriously controversial CoBrA exhibition at the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, in 1949. The exhibition was not well received. Critics were harsh, speaking of offensive art. An evening devoted to experimental poetry, during the same exhibition, resulted in a public brawl.

Danse Macabre – oil on canvas – 119 x 145 cm – 1949 – Stedelijk Museum Schiedam, The Netherlands

Historically, the danse macabre serves as a mediaeval allegory emphasising the inevitability of death. In the visual arts, Death is typically depicted as a skeleton in pursuit of his prey; any dancing that occurs is generally confined to a procession. In Rooskens’ version, a lengthy, colourless, tube-like form meanders over the upper portion of the artwork. This eerie formation emerges from beyond the canvas; there is no beginning and no end. The artist subsequently scatters weird, completely unidentifiable shapes across the canvas. They seem to be floating in space. Ultimately, the indeterminable organism lures the hovering figures into its foreboding trap.

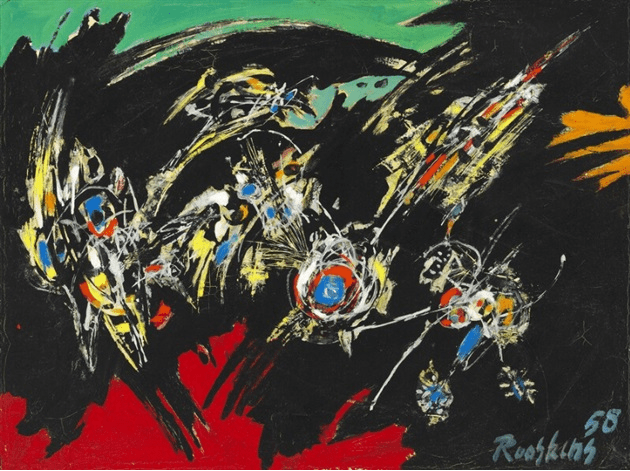

Dancing Insects opus No. 270 – oil on canvas – 60 cm x 81 cm – 1958 – Artnet

The predominant colour in Dancing Insects, like Danse Macabre, is black. Upon this dark surface, Rooskens applies a medley of rough, brightly coloured blotches and splatters. Danse Macabre has a somewhat subtle colour palette. In contrast, the hues collide violently in Dancing Insects; around the edges, asymmetrical shapes in shades of orange, green, and red swoop onto the canvas. Further inward, the space is populated by bizarre multicoloured figures. Some are jagged, spiral, or pointed; some are entangled, and others appear to be airborne. It is intriguing that this artwork, filled with fantastical shapes that vaguely resemble organic forms, was, as was Roosken’s practice, created through improvisation.

Theo Wolvecamp (1925-1992) found his early inspiration in German and Flemish expressionism. Following his exploration of Cubism, he developed a unique style featuring abstract symbols, merging fantastical creatures. He frequently employed deep hues and utilised thick layers of paint. He led a secluded life.

Wolvecamp painted spontaneously, allowing improvisation to be his guide. His artwork is innovative, unbound by any traditions, infused with a deeply personal expressionism grounded in his profound connection with nature.

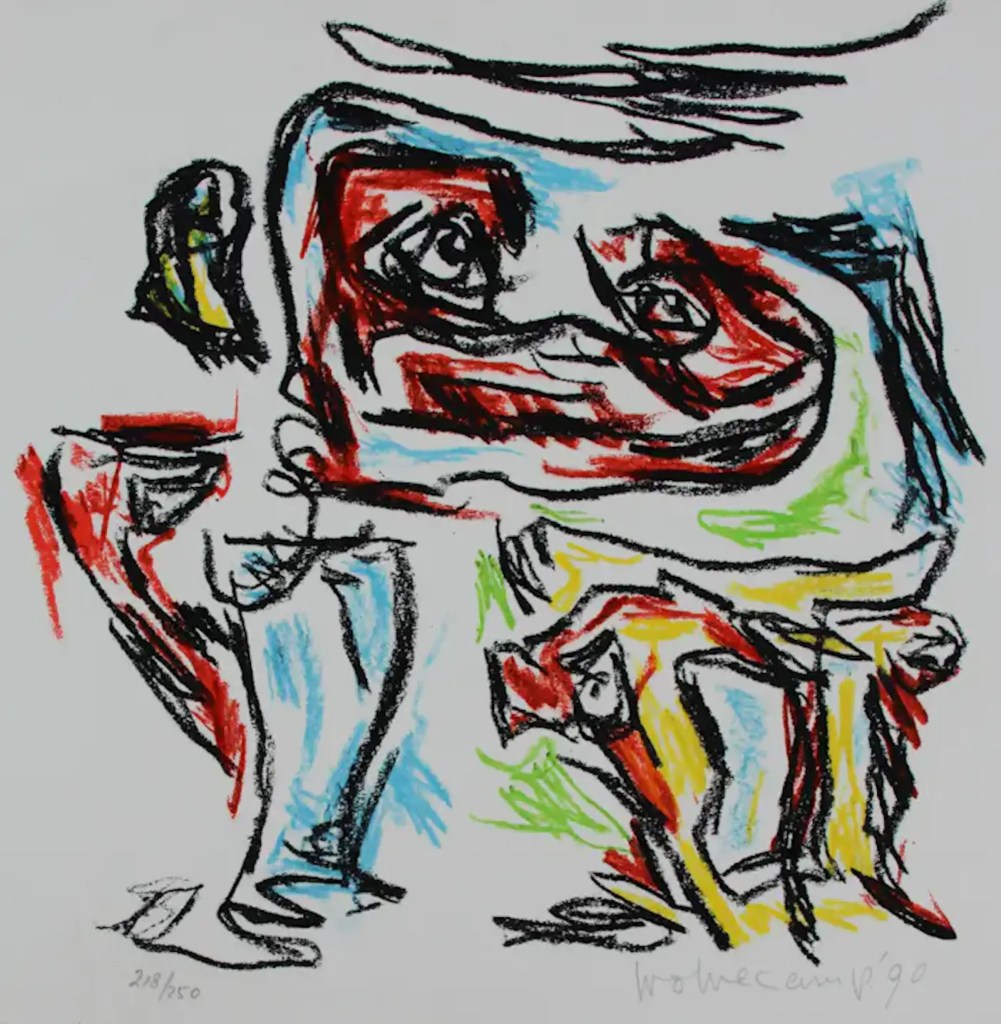

Left: Dancing Couple – 1990 – lithograph on paper – 26 cm x 26 cm

Dancers II – 1990’s – lithograph on paper – 26 cm x 26 cm

KiewitKunst, The Hague – Artpeers

Wolvecamp’s artworks are defined by indistinct shapes and hues. It could be argued that lines, colours, and shapes dance and swirl over his canvas, but to assert that dance significantly influenced his artwork would be an overstatement. After perusing several of his compelling works, I discovered two lithographs depicting a dancing couple. What adds to their fascination is that while many of Wolvecamp’s works lack specific titles or are simply labelled “Composition”, these lithographs carry a title that pertains to dance. Created four decades after the dissolution of CoBrA, the lithographs continue to embody the playfulness, primitivism, and distortion of human figures that characterised the group’s initial stunning work.

The artist utilises straightforward elements: a partially linked, rugged black line to imply the contours of the dancers. The thickness of the lines varies from bold to fine and everything else in between. Some lines consist of just a single stroke, whereas other lines are traced multiple times, resulting in frayed edges. The separate outlines are enhanced by scratchy primary colours and, particularly in Dancers II, pale blue scribbles. Despite the overall roughness, it is evident that the couples are dancing. In Dancing Couple, the man and woman, standing quite tall, dance energetically. One could even say that the red hue hovering above their heads highlights their vigour. The other couple, Dancers II, clasp hands and stoop toward one another, presenting a much less vivacious impression.

Lucebert (1924-1994), the pseudonym of Lubertus Jacobus Swaanswijk, was a poet and artist. He participated in CoBrA briefly, appearing as a poet during the first CoBrA exhibition at the Stedelijk Museum. He was a self-taught artist and only established his reputation as a painter by the late 1950s. Lucebert had a deep passion for jazz and owned an extensive collection of jazz music.

Demon’s Dance/De Dans met de Demonen – 114 cm x 162 cm – 1983 – Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam

In a brief journey through Lucebert’s artworks, I found a series of paintings featuring the word ‘dance‘ in their titles. There is a Demon’s Dance, Night Dance, Dance of the Infidels, Spanish Dance, Dancing in the Mind, Dance in the Heat and my favourite title, I can’t dance I’ve got ants in my pants. These artworks do not show ballet, ballroom dance, folk dance, or any conventional dance style; instead, they are vibrant, colourful canvases entirely occupied by fantastical beings. The beings are bizarre; some possess legs, fins, tentacles, and various other indistinguishable limbs. Many feature a distinctive round shape that resembles an eye. All appear to be organic, but none are identifiable.

Dance of the Infidels – oil on canvas – 98 cm x 127 cm – 1988 – ArtNet

All the ‘dance’ canvases are restless. The colours crisscross constantly. Shapes continually intersect and overlap one another. Is there a connection between this dynamic interaction and dance? Lucebert, as you may remember, was a passionate admirer of jazz. Did he listen to jazz music while he painted? It is known that Keith Haring played music incessantly. Piet Mondrian, a jazz enthusiast, played records while he painted. Studies have shown that Mondrian’s work was strongly influenced by jazz music. Lucebert, like the jazz musician, expresses his individuality through improvisation. Each of his ‘dance’ canvases is asymmetric, swings, and features ‘unexpected sounds’ that evoke an effect akin to blue notes.

I can’t dance I’ve got ants in my pants – oil on canvas – 115.5 cm x 145.5 cm – 1984 – Dordrechts Museum, Netherlands (on loan)

I have to admit that the title I can’t dance I’ve got ants in my pants caught me off guard. Initially, I believed that Lucebert, as an innovative poet, had come up with this amusing title. One might think that having ants in your pants could inspire someone to dance, if only to shake them off. The awesome figures in the artwork offer no suggestions. What connection do these peculiar entities with grotesque faces, devoid of recognisable shape in an unidentifiable environment, have with dancing or, for that matter, ants? I had to investigate further. Another search on the internet led me to a jazz recording that, as you might guess, shares the same title as the artwork. Lucebert, with an extensive collection of jazz music, surely knew the composition. Did he listen to the recording while painting? Did the catchy, syncopated melody inspire the creepy figure with hideous eyes, misaligned nose and protruding tongue? I cannot find definite information to support my idea. However, my online search led me to additional jazz music sharing the same titles as Lucebert’s paintings. The following YouTube links to a 1951 recording by Bud Powell of The Dance of the Infidels and the 1934 recording by Clarence Williams of I Can’t Dance – I’ve Got Ants in My Pants may provide some insight into Lucebert’s approach.

In an earlier post, I mentioned that Karel Appel was involved in multiple theatre productions, designing costumes and sets for opera and contemporary dance. He was not the only member of the short-lived CoBrA group to work in the theatre; Constant and Anton Rooskens designed the décor for a ballet by Sonia Gaskell, founder of the Netherlands Ballet. Her distinctive production, The Chairs, premiered in 1955. In the same year Constant and Rooskens also created the costumes and set for The Trial, a choreography by Jaap Flier.

De Appelwand/ The Appel Wall – inside the foyer – 25 meters (b) x 6 meters (h) – 1970 – Hofpleintheater, Rotterdam

Karel Appel, like many of his fellow artists, did not limit himself to just painting. Their creativity and innovation ventured into the visual arts, performing arts, urban planning, and architecture. The vibrant, glass-in-cement wall depicted in the two photographs is an artwork by Karel Appel created for a youth theatre in Rotterdam. Imagine the effect—a myriad of hues that illuminates the foyer on a sunny day. And in the evenings, an array of colours that radiates over the vast expanse in front of the theatre.

De Appelwand/ The Appel Wall – 25 meters (b) x 6 meters (h) – 1970 – Hofpleintheater, Rotterdam

To this day, CoBrA remains unconventional, innovative, daring, and provocative. CoBrA, to quote Appel, was a ‘crossroad’. Artists ‘crossed paths and each continued on his way. ‘ Their paths led to manifold directions. Their impact knows no bounds.