CoBrA, the short-lived yet highly impactful art collective, challenged conventional art movements and rejected bourgeois art. The artists were unconventional, innovative, daring, and provocative. The Dutch, Belgian, and Danish artists were influenced by Paul Klee and Joan Miró, as well as children’s art, outsider creations, naïve art, and primitive artistic expressions. CoBrA, an acronym for Copenhagen, Brussels, and Amsterdam, was founded in 1948. The group dissolved in 1951, leaving the individual artists to explore experimental avenues. The previous post examined dance images and theatrical work by Karel Appel; it is now time to delve into the dance-related images and designs of Constant (1920-2005) and Corneille (1922-2010), both founding members of CoBrA.

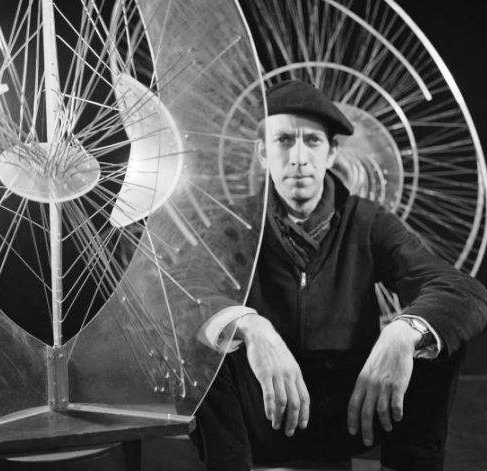

Corneille – 1986 – photograph De Parool

Fauna – oil paint on canvas – 75 cm x 85 cm – 1949 – CoBrA Museum voor Moderne Kunst, Amstelveen

Corneille

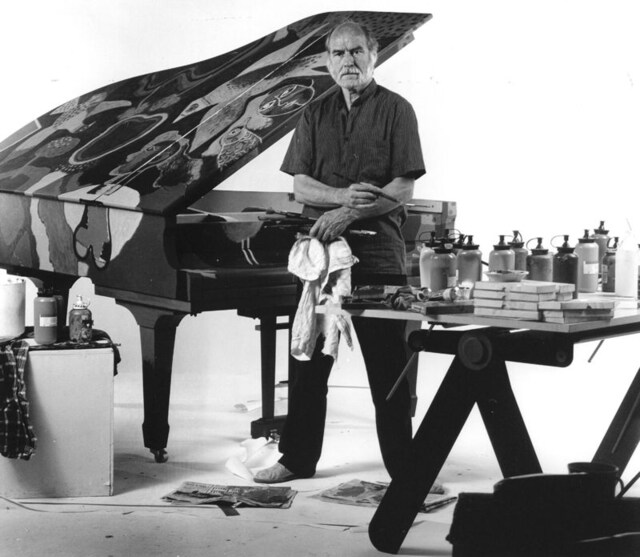

Vis/Fish – 1950 – watercolour – 50.3 cm x 38.6 cm – Collectie Stedelijk Museum,Schiedam

Constant Anton Nieuwenhuys, in short Constant, was a uniquely skilled individual. He was an artist, sculptor, graphic designer, writer, and musician. He is often regarded as the theorist of the CoBrA group.

Corneille, pseudonym of Guillaume Cornelis van Beverloo. was a painter, sculptor, graphic artist, and poet. Following the dissolution of CoBrA, Corneille relocated to Paris, where he collected African art.

Constant, having witnessed the devastation of war, envisioned a new cultural and social structure in which the automation of production would grant humanity increasing periods of leisure. He spent more than ten years crafting his ideas for a progressive society, New Babylon.

Corneille stated, “I am a painter of joy.” Since the late 1960s he has created vividly coloured figurative art, focusing on tropical landscapes, women, animals, and plants. He gained worldwide recognition.

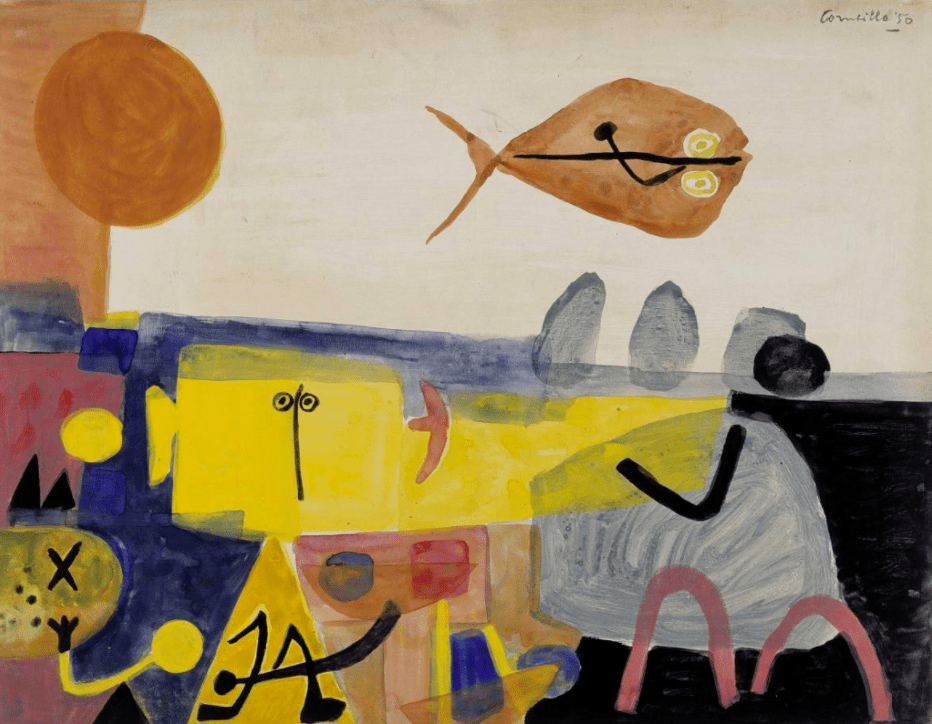

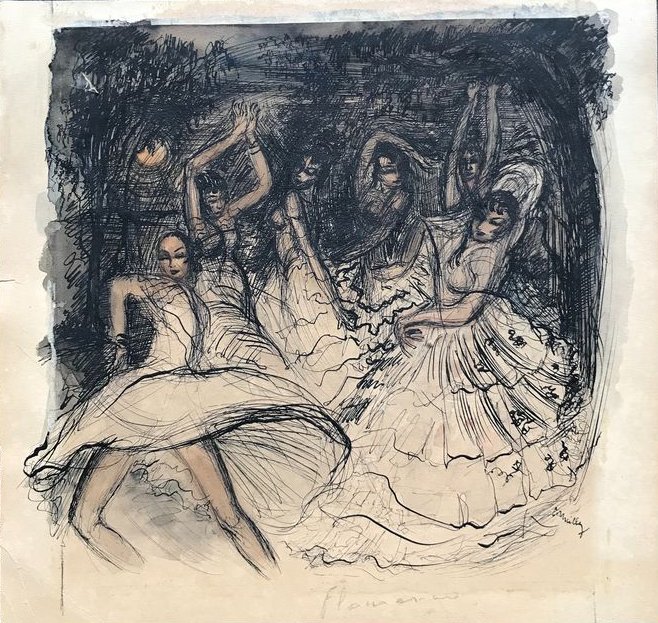

Corneille excelled in drawing. He attended the Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten in Amsterdam, where he formed a friendship with Karel Appel. While browsing various websites, I stumbled upon this amazing drawing of flamenco dancers, created before the establishment of CoBrA. Why amazing? Each and every dancer moves vibrantly. The dancers at the front instantly capture our focus. The graceful dancer on the right beautifully embodies the traditional Spanish style. On the other hand, the dancer on the opposite side is genuinely mesmerising; observe the swirling skirt, the dynamic thrust of her legs, her taut torso, and the iconic flamenco arm position. She is a truly passionate dancer. The four background dancers, while not as prominent, are captivating and draw the viewer in with their seductive expressions. Corneille captures movement and emotion on a two-dimensional surface.

Flamenco – Indian ink and watercolour on paper – 22 cm x 23 cm – c. 1945 – Catawiki (with a certificate of authenticity from the Guillaume Corneille Foundation.)

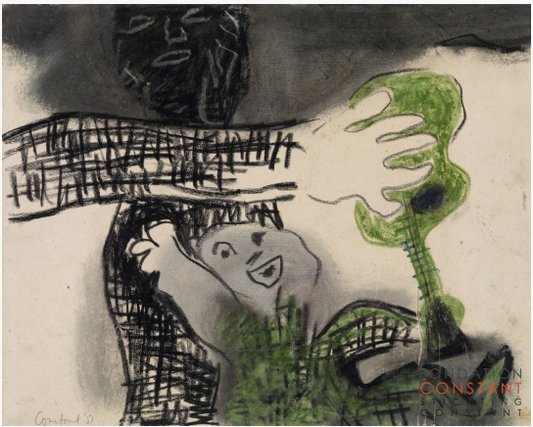

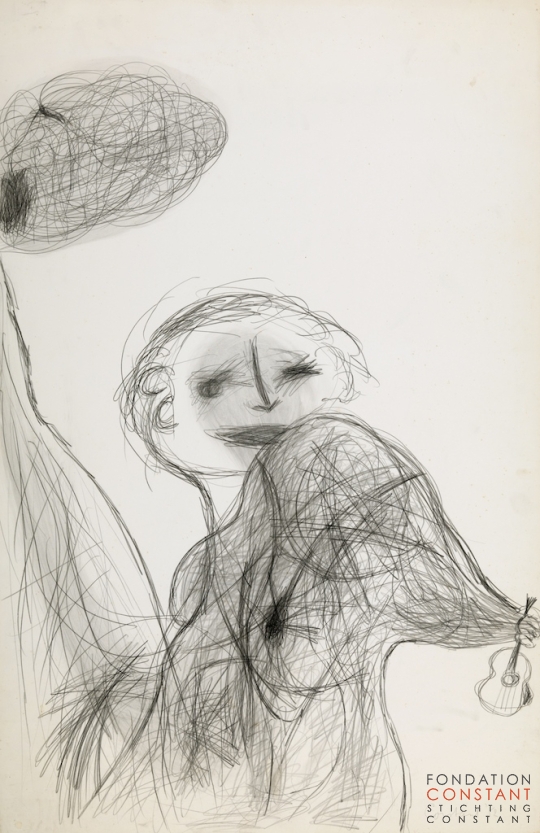

Constant was a remarkable musician. He performed the violin and cimbalom in addition to being a proficient practitioner of the Spanish guitar. He cultivated a passion for gypsy music and was captivated by flamenco music and dance. Fandango, an artwork created during the CoBrA period, was inspired by the Spanish music and dance form. From that original piece, produced in 1951, flamenco and various traditional Spanish music and dance forms regularly appear in Constant’s work.

Constant Left: Fandango – chalk, charcoal, gouache & paper – 36.5 cm x 45.5 cm – 1951 Right: La danseuse Espagnole – pencil on paper – 100.1 cm x 64.5 cm – 1952 Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam – Fondation Constant – photographer Tom Haartsen

The Fandango is a lively Spanish dance performed by couples. It is accompanied by clapping, guitar playing, singing, and castanet sounds. Constant’s interpretation of this animated dance is atypical. His drawing of a guitar, a large arm with big fingers, an energetic musician, and an animated Spanish dancer are all rendered with childlike simplicity. The lines are slipshod, the shapes disordered, and while all the typical fandango components are recognisable, they remain crude and exaggerated. Constant employs a comparable method in La danseuse Espagnole, another work created at the height of CoBrA experimentation.

Constant envisioned a world, as the historian/philosopher Johan Huizinga did, where “Man will develop … into a ‘homo ludens’, a playing man, creative, free of work and free from borders.” For New Babylon, as this project was called, Constant created models, constructions, paintings, and drawings. He further altered current geographical maps of various cities, reshaping them into his concept of the perfect city. The New Babylon conceptualisation of Sevilla is segmented into areas named after the Flamenco : Caña, Malagueña, Soleares, Alegría, Fandango, Sevillana, Siguiriyas, and Tarantos. The significance of flamenco to Constant is further demonstrated by a collection of fabrics created around 1956 – Fandango, Malagueña, and Saeta – all of which were named after styles of flamenco music and dance.

Street Musicians – 1988 – dimensions not given – Collection Unknown

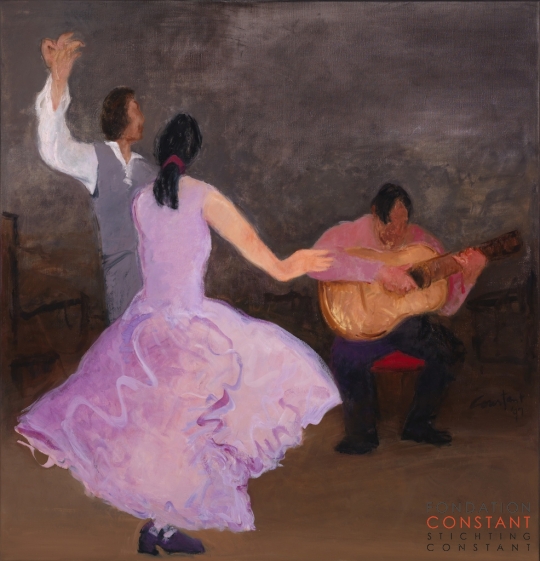

Flamenco – linen, oil paint – 194 cm x 185 cm – 1997 – Collection Fondation Constant

Collection Fondation Constant,Stichting Constant

In Street Musicians, a gouache made in 1988, Constant depicts a roaming street musician entertaining passersby. The limited palette of earth tones – yellow-brown, maroon, olive green, and a lighter shade of yellow – contrasts with a background of different shades of grey. The only bright light falls on the musician’s face. His features, though vague, are distinguishable. He appears to enjoy an animated conversation with a man wearing a Spanish riding hat. A friendly atmosphere lingers in Street Musicians, and the same is evident in Flamenco, a dance artwork created a decade later. The scene feels familiar: a seated guitarist accompanying a dancing couple. The couple’s expressive arms are highlighted, as is the rhythmic footwork of the woman, complementing her partner’s steady clacking of the castanets.

Corneille was among the most revolutionary CoBrA artists. In his CoBrA period, as far as I could discover, he produced no dance images or images related to dance. A decade later, in 1961, he created an exceptional abstract lithograph, Danse des insectes dans l’herbe, l’été, as a component of a collection titled ‘Six propositions pour un spectacle de la nature’.

Danse des insectes dans l’herbe, l’été – paper, ink – lithograph – 50,5 x 65,5 cm – 1961 – Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem

Upon seeing the title, I felt compelled to explore the artwork and discover the dancing insects. Initially, the disorder held me back. How to discover dance amidst so much intricacy. The numerous layers of ink, intricate designs, countless lines, and vast areas of black contrasted with endless smears and patches of earth tones seemed, to me, impenetrable.

While I examined the intricate designs of this lively composition, I allowed my thoughts to drift to a sunny summer afternoon filled with butterflies, moths, ants, and arthropods intermingling, soaring, scuttling, climbing, and buzzing everywhere. Corneille has captured this energetic atmosphere. Examining his chaotic scene more closely uncovers a dominant ant, a butterfly, a super-sized centipede, and a swarm of creepy-crawlies. Surprisingly, at the heart of it all sits a substantial key-shaped object, the only stationary feature amid a flurry of movement.

After CoBrA. Corneille describes how his artwork progressed from lyrical abstraction to landscapes influenced by his journeys in Africa, eventually transitioning to figurative painting. In his later years, Corneille created joyful, stylised pieces showcasing birds, flowers, women, cats, and other popular subjects portrayed in vibrant hues. Corneille emerged as one of the most renowned Dutch artists of his era, achieving international acclaim. He reached an even broader audience through merchandising. His designs embellishing neckties, ceramic plates, beer containers, and wine bottles have seen great commercial success. Yet there are few images of dancers actually performing; with a bit of perseverance and plenty of online searching, I was able to find some dancing figures.

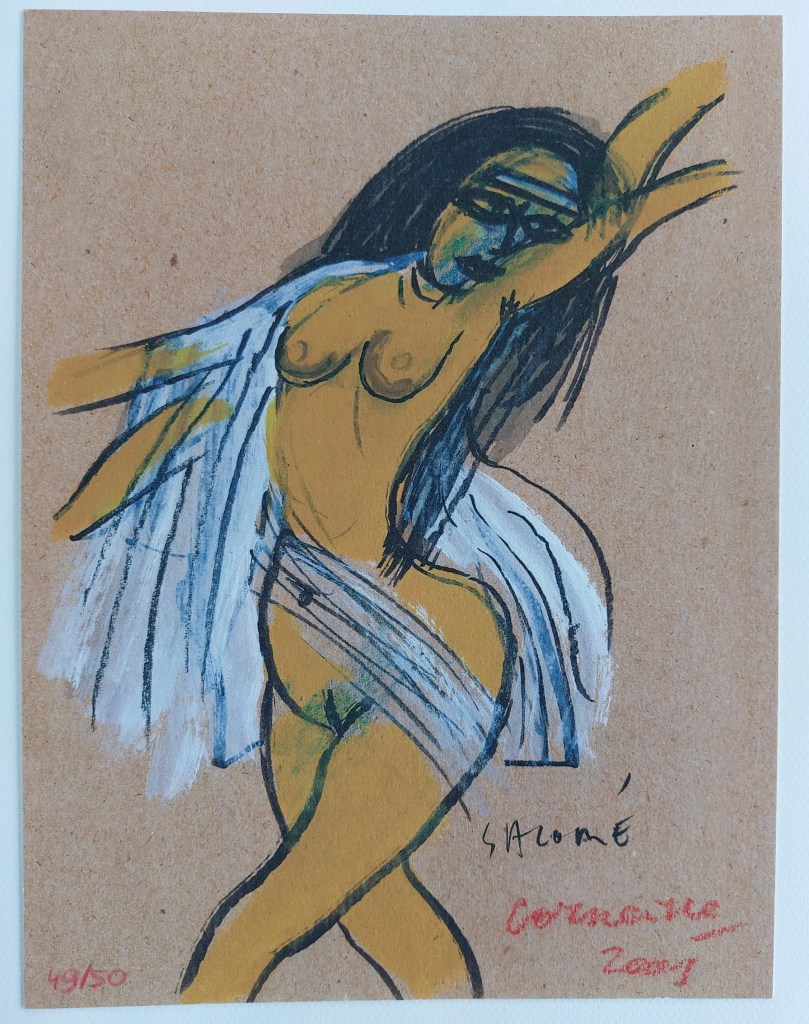

Left: Salomé dancing for Herod (one of the original serigraphs taken from Corneille Salomé) 2001

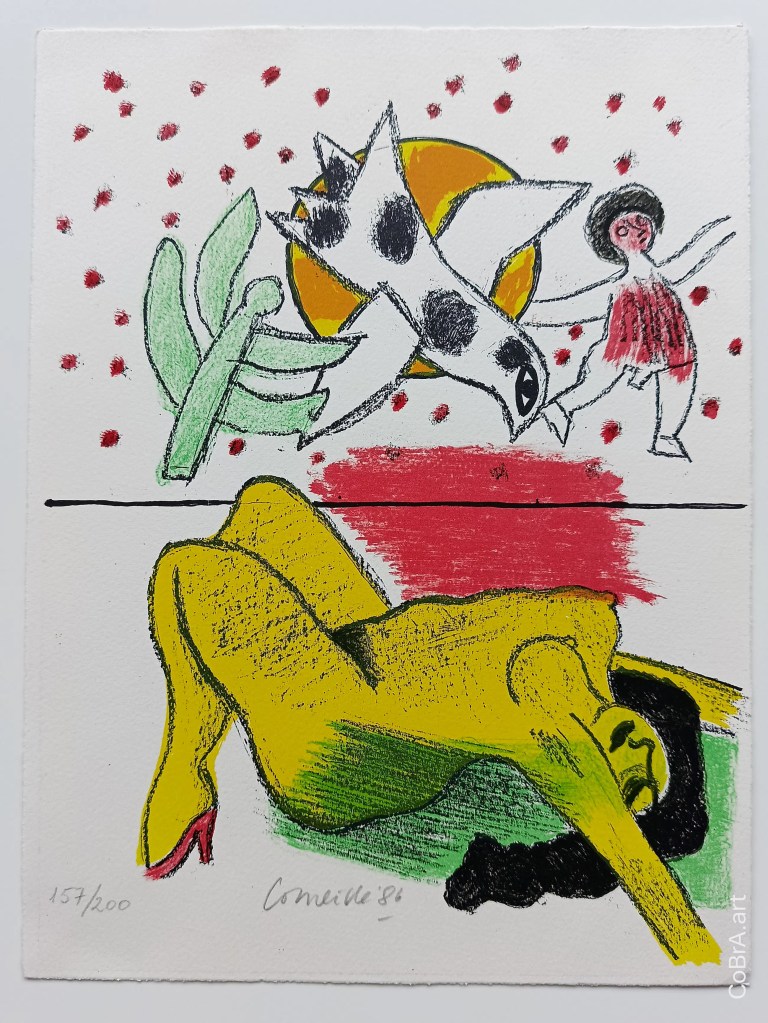

Right: Woman and Bird: Dancing in the Sun – lithograph – 34 cm x 26 cm – 1986 – Kunstveiling

Salomé, the name alone evokes visions of a captivating young female whose beguiling dance led to the execution of John the Baptist. In 2001, Corneille produced thirteen unique serigraphs to illustrate Oscar Wilde’s bold reinterpretation of the biblical tale. Corneille depicts Herodias’s daughter, similar to Wilde, as a famously alluring seductress. His femme-fatale is bewitching. It is obvious that she is dancing; her torso is rotated, her legs suggest activity and by duplicating the arms Corneille, like a overexposed photograph, implies fluctuating arm movements. The dancing is further highlighted by Salomé’s free flowing veil swinging around disrobed body.

The figures in the upper section of Woman and Bird: Dancing in the Sun resemble drawings from a child’s colouring book. The dancing figure, like the bird, sun, and cactus, is formed by a black outline and then completed with colour or shading. The dancer, similar in size to the sun and smaller than the bird, capers joyfully among ornamental red and black spots. Are these ladybirds? These stylised figures likely represent the thoughts of the alluring nude suggestively sunbathing in the lower part of the artwork.

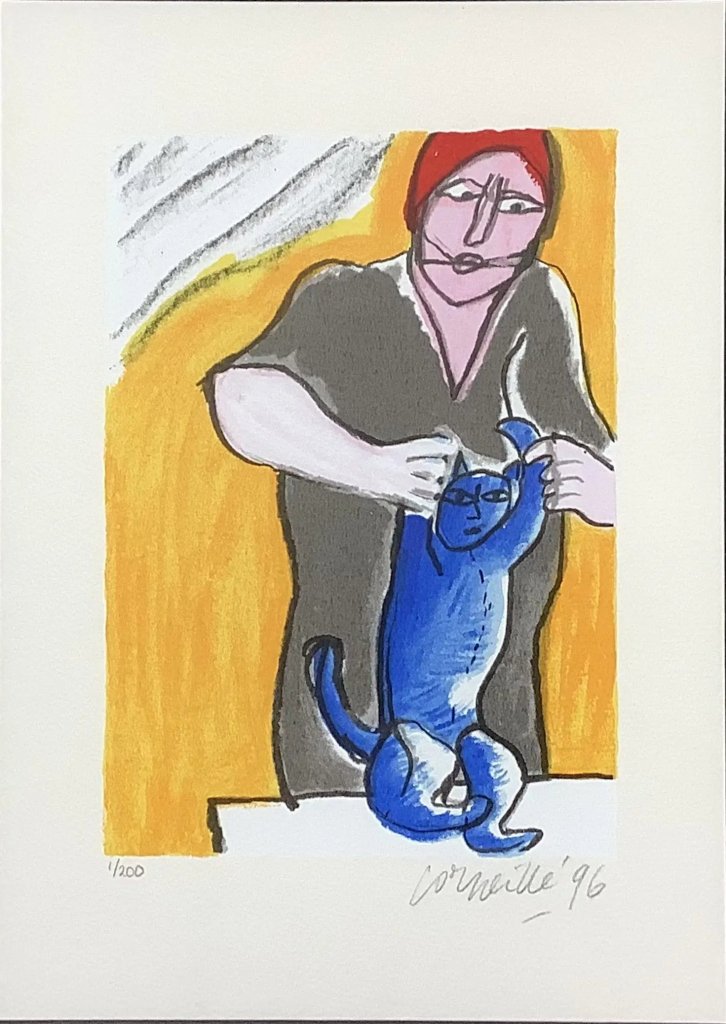

The following two works featuring an anguished cat are divided by three hundred years of art history. The Dancing Cat (Le Chat qui danse) traces back to Jan Steen‘s extraordinary painting. Corneille’s blue cartoon-like feline may have a more affable nature than the distressed cat in the earlier artwork, but the resemblance is evident; both cats are elevated by their front legs, both are confined, and both raise their right paw. The men have changed over time; Corneille’s character appears malevolent, whereas Steen’s dancing master, despite his harsh handling of the unfortunate cat, appears good-natured. Certainly, this isn’t the dance one typically anticipates; however, I have incorporated them as the artist mentions dance in the title.

Le Chat qui danse – silkscreen print – dimensions work: 38 x 28 cm, dimensions image: 22 x 17.5 cm. – 1996 – Kunstveiling

Jan Steen

Children Teaching a Cat to Dance (The Dancing Lesson) oil in canvas – 68.5cm x 59 cm – c. 1660 -1679 – Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

The pioneering artists Constant and Corneille, founding members of the groundbreaking post-war art group CoBrA, in Karel Appel’s words, “crossed paths … to follow their own path.” Their journeys are varied; their lineages are paramount.