How can one define CoBrA? Non-traditional, original, bold, and provocative. The term CoBrA, an acronym of the capital cities of its founding artists—Copenhagen, Brussels, and Amsterdam—was coined by Christian Dotremont. CoBrA was established in 1948. The artists, including Karel Appel, Constant, Corneille, Christian Dotremont, Asger Jorn, and Joseph Noiret, rejected both naturalism and abstraction. They questioned established art movements and dismissed bourgeois art, drawing inspiration from children’s artwork, outsider art, naïve art, and primitive art forms. They celebrated the works of Paul Klee and Joan Miró and shared a common interest in Marxism. Karel Appel (1921-2006) particularly embraced the spontaneity and unrestrained creativity present in the art of children.

Questioning Children – Gouache on pine wood – dimensions object: 873 x 598 x 158 mm – 1946 – presented by the artist in 1986 – TATE, London

Appel prepared the surface of Questioning Children by nailing discarded pieces of wood to an old window shutter. The vibrant colours and roughly-painted figures recall the spontaneity of children’s art. CoBrA artists believed that such unconventional sources could re-invigorate post-war culture. – Tate, London – Catalogue Entry

CoBrA distanced itself from the art establishment. The revolutionary movement, despite its brief existence, had a major impact on modern art. The group dissolved in 1951, leaving the individual artists to explore experimental avenues.

In CoBrA, traditional dance images are non-existent. Appel, Constant, Corneille, and Lucebert – Dutch and Belgian members of CoBrA – approached dance in the broadest context imaginable. The result: multi-coloured, semi-abstract, humorous, unexpected and unconventional images.

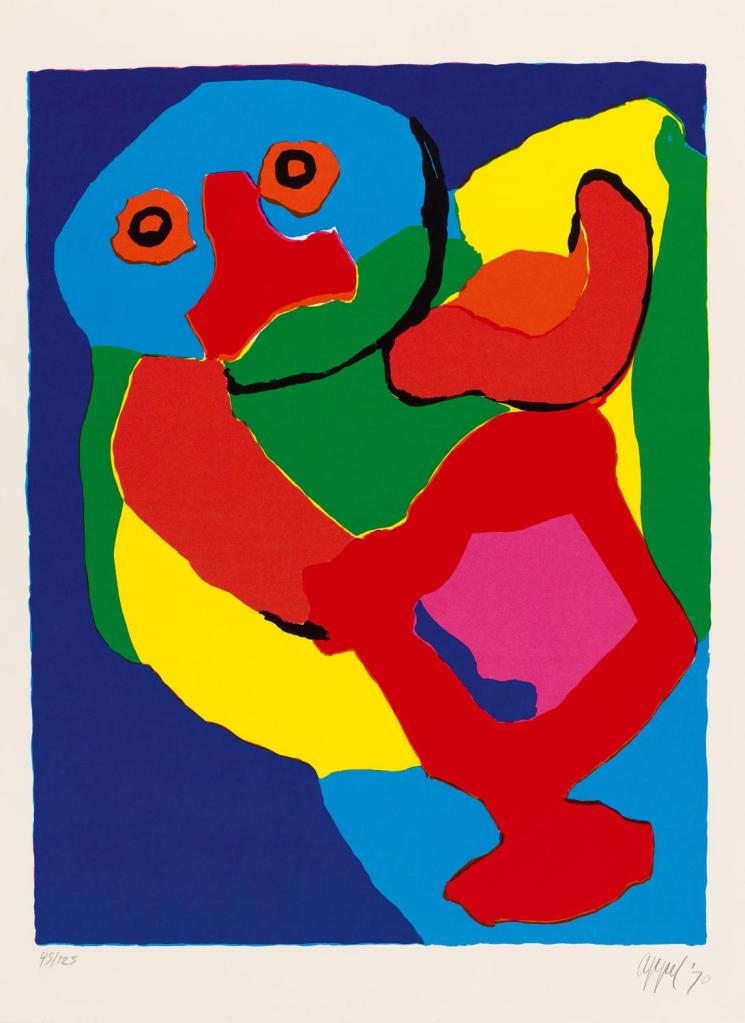

Left: The Dancing Man – nr.41 / 125 – 66.5 X 50.5 cm – 1970 – Colour Lithograph on Cardboard – Van Ham Auctions, Cologne

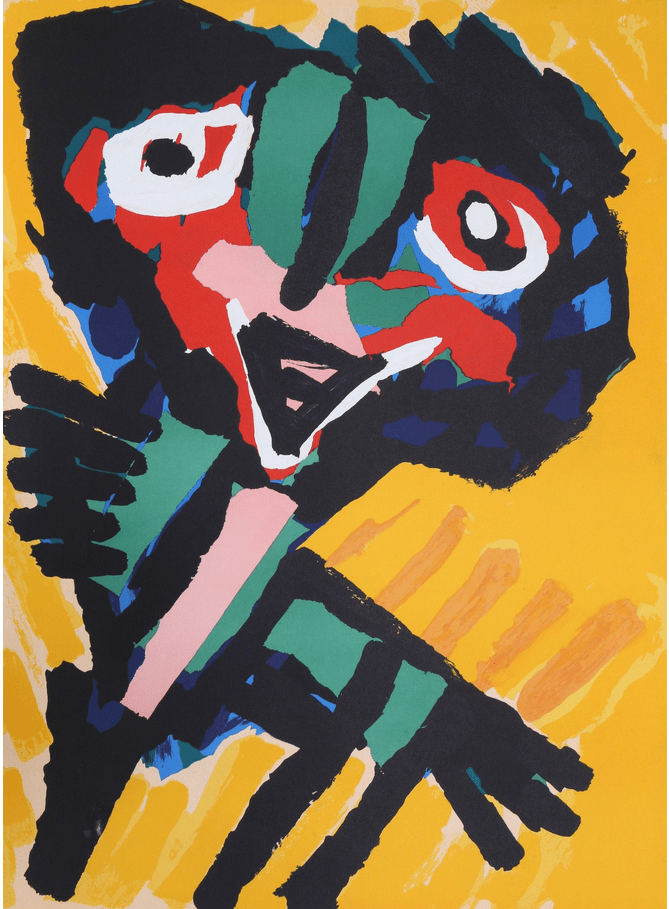

Right: Dancing Figure (also titled Dancing Girl) – Lithograph – 76.2 X 55.88 cm – 1979 – RoGallery, New York

Christiaan Karel Appel, the Dutch artist whose work is on par with Piet Mondrian and Willem de Kooning, incorporated identifiable forms into his artworks. He illustrated, painted, and sculpted birds, children, animals, and various other lifelike figures. Sometimes the figures are easily recognisable, while at other moments Appel nearly approaches the brink of the non-representational. The Dancing Man and Dancing Figure, shown above, are humanoid forms depicted in slabs of primary and secondary colours. These are amiable, appealing characters. The big red eyes of The Dancing Man are directly aimed at the audience. I feel the urge to liken him to a sorrowful teddy bear. In contrast, the Dancing Figure is lively. So lively that ‘she’ nearly pops out of the background. Characteristic of Appel are the intense dark outlines placed alongside vibrant hues. Both artworks, made in the 1970s, reflect Appel’s unique style. The lithograph Dancing Figure/Dancing Girl led to the creation of a virtually identical wooden sculpture some years later.

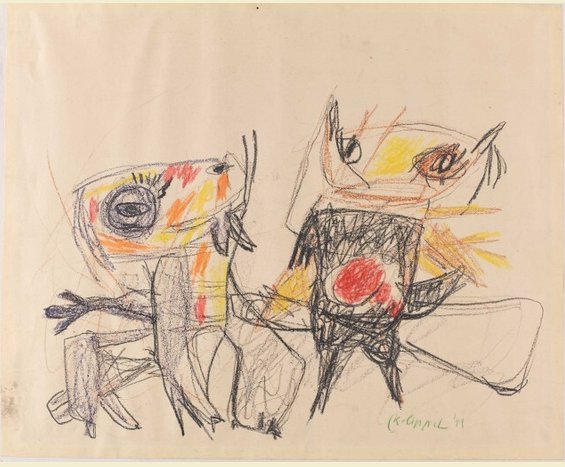

1) Karel Appel – Desert Dancers – oil on canvas – 115.5 x 164 cm – 1954. Courtesy Musée d’Art moderne de la Ville de Paris, Karel Appel Foundation 2) Karel Appel – Sketch of the Desert Dancers – wax crayon on paper – 50 X 61 cm – 1949 – Kunstmuseum, The Hague

The ochre background is the only indication that the two figures on the canvas are situated in the desert. The setting raises the question of whether the yellowish background truly indicates an endless sandy terrain or if Appel, adopting a more philosophical mood, implies an infinite void. Desert Dancers is an expansive artwork. The sketchy dancers, insects or animals stand at least a metre tall. The figures seem to have been drawn quickly. The thin pencil strokes, the unevenly shaded spots with colour spilling over the edges, the asymmetrical figures, and the coloured lines criss-crossing over the canvas are typical of children’s drawings. Even the exaggeratedly large black eyes are fashioned in a childlike manner. On top of the actual dancing figures, Appel adds uneven blotches and streaks of white, blue and grey paint. Appel, who encountered Vincent van Gogh’s work as a young lad, was captivated by the artist’s restless brushstroke, a characteristic he continued to develop in his own fashion.

Asked about his working method, Appel scintillatingly commented, ‘I am just messing around.’ Far be it from me to question the great artist, yet it is worthwhile to pause and consider his preparatory sketch from 1949 for Desert Dancers. The sketch depicts a rough draft of the two dancing figures featured in the 1954 painting. The resemblance is striking; the eyes, the ears, and the physical forms of the figures are almost identical. In a similar manner, the shading and markings are alike. Most intriguing is the red circular form situated in the centre of the taller figure’s ‘body’. That also appears in the completed artwork, making me question if Appel just ‘messed around‘.

Amorous Dance / Danse amoureuse – oil paint on canvas – 1140mm x 1460mm – 1955 – Tate, London

An explosion of colour? Chaos? Unrestrained energy? The title Amorous Dance evokes certain expectations. Are we standing on a balustrade gazing down at a dance floor crowded with individuals who are dancing with unbridled abandon? The exploding colours and frenzy of brushstrokes may represent the swirling, darting, jumping, and frolicking of the exuberantly passionate crowd. There could, nonetheless, be an alternative interpretation. I noted earlier that Appel, although at times tending toward abstraction, consistently represented corporeal figures. Amorous Dancers embodies the indistinct contours of two dancers. They practically blend into the background. Their ears, eyes, and other appendages vaguely mirror the dancers in Desert Dancers. It is not inconceivable to envision Amorous Dancers as a portrait of a passionate couple engulfed in a whirlwind of intense emotions.

The expansive canvas, eloquently titled Dance in Space before the Storm, is astonishing. The title featuring the terms ‘dance‘ and ‘storm‘ could indicate the artist’s intention. The background is relatively light; various hues of white and grey randomly intermingle. The erratic swirls and blotches of rotating paint, alongside the red, yellow, and dark circular lines, create an unfathomable disorder. The two dark areas are foreboding. The upper scattered region might suggest a threatening accumulation of clouds. In the bottom right corner, the thick black cloud signals the impending danger of a fierce storm. This literal interpretation raises the obvious queries. Are we looking at a natural phenomenon, or is Appel suggesting a tempest of internal emotion?

Danse d’espace avant la tempête/ Dance in Space before the Storm – oil on canvas – 129.50 x 161.90 cm – 1959 – National Galleries of Scotland

Of particular interest is that, for Dancer … Appel applied paint directly from the tube onto the canvas. In other areas, he used his bare hands to smear the paint over the canvas. Appel is famously quoted stating, ‘I don’t paint. I hit’, which literally refers to him throwing paint on the canvas. Equally interesting is that Dancer… was painted after Appel visited New York, befriending his compatriot, the abstract expressionist Willem de Kooning.

Appel was an accomplished poet. The imaginative titles he assigned to his artworks — Three Faces like Cloud, Dance in a white space, and my favourite, The Crying Crocodile Tries to Catch the Sun —provoke original thought. Appel was also a man of the theatre. In 1962, he collaborated with the renowned Dutch poet, Bert Schierbeek. In 1994, Appel collaborated with the dancer/choreographer to produce the dance performance Can we dance a Landscape?. Appel, in an interview, explained that he viewed dance as a form of visual art, specifically, moving visual art.* The Butoh master Tanaka also served as choreographer for Noach, an absurdist opera directed by Pierre Audi. Karel Appel created ten backdrops and fifty animals, one of which is a six-metre-long styrofoam whale.

Noach – Guus Janssen (composer) – production Pierre Audi 1994

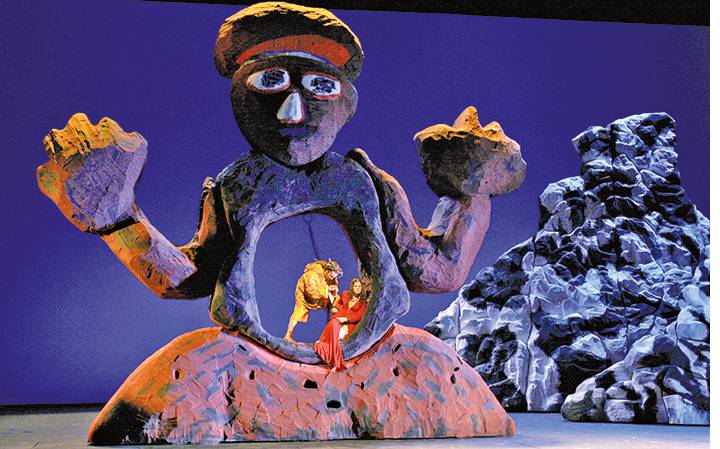

Stage design for Die Zauberflöte – Mozart – Salzburg Festival ( originally produced for the Nederlandse Opera Stichting in 1995)

The subsequent remarkable production, once more with opera-theatre director Pierre Audi, was the opera Die Zauberflöte in 1995. Appel designed the sets, fantasy animals and mythological figures. The dimensions and colours of the sets in both Noach and Die Zauberflöte are awesome; they command the stage. The props are stunning and uniquely functional. The tip of the tongue of the ferocious creature in Noach serves as a podium for the performers. Similarly, in Die Zauberflöte, the performance space is imaginatively maximised; the artists act within the abdomen of a massive doll.

Karel Appel is undeniably linked to CoBrA. His remarkable early creations, however, originally received little recognition and sparked significant debate. The artworks faced criticism, with both critics and the public asserting that any child could create pieces similar to Appel’s. That viewpoint has appropriately altered. Appel is certainly not restricted to CoBrA. His humorous, ambiguous, profound and thoroughly delightful work, created over more than half a century, continues to intrigue and captivate the viewer. In the words of Karel Appel :

“Of course, I painted before Cobra, as afterwards. Each one of us [CoBrA-artists] had his own personality. Cobra is only a very short period of my life. It was like a crossroads. We crossed paths and each continued on his way…. We [artists] are not born to form groups. A group that lasted for too long would destroy the creative activity of its members.”

*Interview – Liefde voor al wat rauw is – Max Arian – De Groene Amsterdammer – 16 November 1994. The interview is in Dutch, the translation is mine.