Artwork depicting dancers taking ballet classes or portraying individuals during dance lessons is relatively uncommon. Edgar Degas, of course, painted dancers training at the barre and rehearsing under the watchful eye of the ballet master, but Degas stands out as the exception. Artists hailing from The Low Countries are renowned for their peasant and social dances, but I know of few paintings depicting dance classes, ballet lessons, or dancers in the studio. Curious, I decided to explore.

The earliest painting I discovered is Love Garden with Elegant Figures (1596), a joint creation by Hans Vredeman de Vries (1527-1606), his son Paul Vredeman de Vries (1567-1630), and Dirck de Quade van Ravesteyn (1565-1620). De Vries and his son developed the architecture, while van Ravesteyn contributed the staffage. This painting, one of a series of four major architectural works, was created in Prague for the court of Rudolf II of Habsburg, Holy Roman Emperor. The grandeur of this architectural fantasy showcasing distant views, an elegant colonnade, marble columns, and a finely decorated fountain might have distracted you from the dancing class. If you focus on the lower left corner of the canvas, you will see a dance master teaching an elegant boy and courteous girl the art of court dancing. As was customary at the time, the dance master accompanies the lesson by playing the violin. Beneath the second arch, two courtiers are observing the lesson.

Love Garden with Elegant Figures – oil on canvas – 137 cm x 174 cm – 1596 – Kunst Historisches Museum, Vienna

Aristocratic youngsters were required to study court etiquette. Mastering court dancing was essential. We can only speculate about which dance these children are practicing. Their dance program could include the then fashionable dances as the pavane, the allemande, the courante, or the bourrée. The girl, despite her youthful age, is poised and has an aristocratic manner. The sprightly boy, in contrast, bounces or hops on one leg. He may be practicing a lively galliard, or perhaps he’s simply playing around.

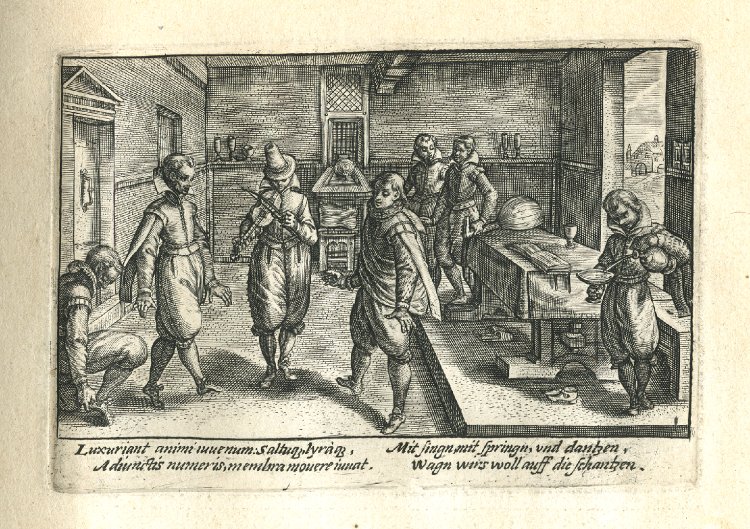

Crispijn de Passe the Elder (c. 1564-1637), engraver, draftsman, and print publisher, composed the book Academia sive Speculum Vitae Scolasticae, to inform students and interested parties about the honourable and less virtuous aspects of university life. Engravings showing the hortus botanicus, a game of tennis, the library, and graduation represented respectable aspects. The engraving of the dance class, a more dubious pursuit, was allocated to the frolicsome category of activities. During de Passe’s era, the Dutch Republic boasted two universities, Leiden University and Franeker University. Each had a dance master assigned to its staff. Dance, it seems, despite the condemnation of the church, was considered an essential aspect of a young man’s education. Commoner Constantijn Huygens (1596–1687), for instance, secretary to the court of William of Orange, encouraged his sons to take fencing, riding, and dancing lessons.

Dancing Lesson – Series: Academia sive Speculum Vitae Scolasticae – engraving/etching – 96 mm x 139mm – 1612 – British Museum

In this scene of academic life, a dance master, playing the violin, instructs two male students in the art of dancing. Please note there are no female companions present. The young men entertain themselves by dancing, drinking, and playing music. One of the students is carrying a lute. The Latin/German inscription emphasises the joy of dancing, even challenging the men to perform jumps. A pleasant scene, or so it appears, if it were not for the explanatory commentary written on the page opposite the illustration. The reader is reminded that the dance of the ancients was both dignified and structured. The writer laments that the ‘new dance‘ requires the entire body to move without constraint. The passage continues by quoting Cicero, who states, ‘For hardly any man dances when sober,’ underlining that contemporary dances are akin to the actions of a fool. The commentary adds that those who engage in dancing follow in the footsteps of fools. This engaging image, together with the accompanying text, makes the issue concerning social dance distinctly evident.

Pieter Codde

The Dancing Lesson – 40 x 53 cm – oil on panel – 1627 – Musée du Louvre, Paris

Dancing schools, regardless of religious or ideological opposition, emerged throughout the country. Dance masters worked at court and were employed by affluent families. In Pieter Codde’s (1599-1678) painting The Dancing Lesson, a dance master instructs an elite couple. Codde, recognised for his genre pieces, situates the scene in a sober, yet privileged, setting. The handsome painting on the rear wall, the large luxurious table covering, and the modest but costly clothing all confirm the family’s prestigious social status. It is often challenging, if not impossible, to determine which dance is being performed. The limitation of the dancing area suggests that this dance takes place in a confined space. The couple moves very little, indicating they are executing a serene, dignified dance that emphasises footwork and floor patterns, with a minimal embellishment of the upper body. A polite dance that is ideally suited for the Calvinist society.

The Dancing Lesson, along with the painting featured at the beginning of this post, Love Garden with Elegant Figures, is the only Dutch artwork I found that showcases a dance master instructing nobles in etiquette and dance. It is intriguing that neither of these artworks was intended for patrons in The Netherlands; rather, they were commissioned by foreign aristocrats. In both French and Italian art, illustrations of ballet masters are more prevalent.

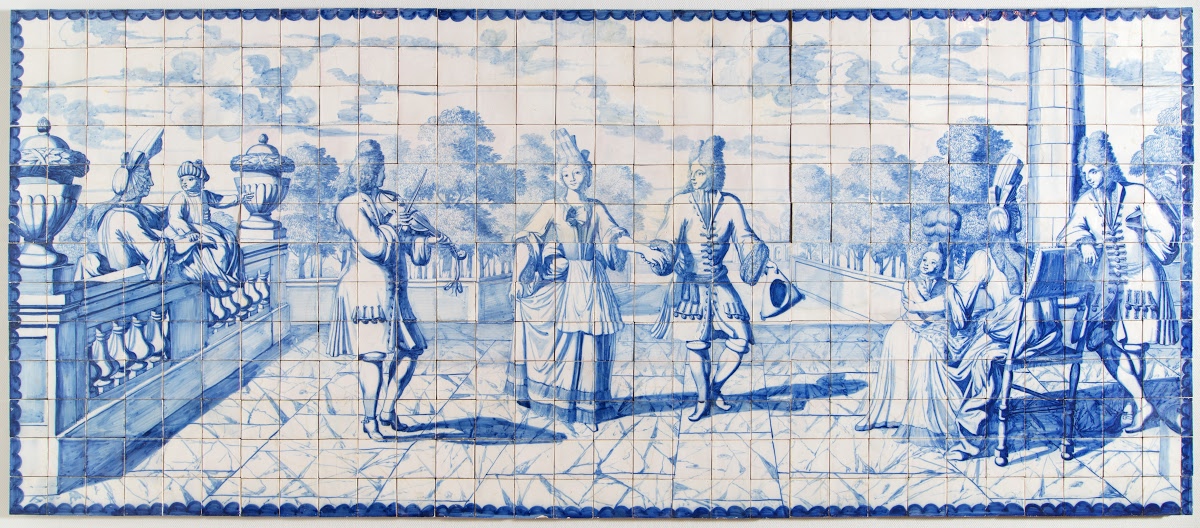

Willem van der Kloet/ Jan van Oort – The Dancing Lesson – 170cm x 400 cm – c.1707 – National Tile Museum – Lisbon

Beginning in the latter part of the 17th century, Dutch ceramic artisans, influenced by Chinese porcelain, developed the blue and white Delft tile. Renowned for their technological and artistic skills, these artisans received commissions from foreign clients, especially from Portugal. Extensive tile panels were designed and produced in the workshops of ceramic artists like Jan van Oort (1645-1699) and Willem van der Kloet (1666-1747). Their impressive blue and white tiled mural, The Dancing Lesson (170 cm X 400 cm), was designed for the Galvão Mexia Palace in Lisbon.

The grand palatial scene displays a dancing master instructing an ornately attired couple. Other aristocrats are positioned on either side of the panel, enjoying the music, the dancing, and the sunshine. The dance master, with a violin in hand, is teaching the gracious couple a fashionable court dance; perhaps a passepied, a gavotte, or a minuet. The dancers embody the essence of elegance. The artist meticulously depicts the gentleman’s footwork, the positioning of his tricorn, and the genteel manner of holding his partner’s hand. The elite lady poses beautifully, her skirt held delicately between her thumb and index finger. She also extends her little finger affectively outward. She is a striking example of decorum, capturing our attention with her compelling gaze. That gaze, considering the lifelike height of the dancers, is directly aimed at the viewer. Perhaps that very gaze prompted the preeminent Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas to revisit the mural. A reproduction of Van der Kloet’s image now adorns the VIP Hall of the Casa de Música, an ultra-modern concert hall in Porto designed by Koolhaas.

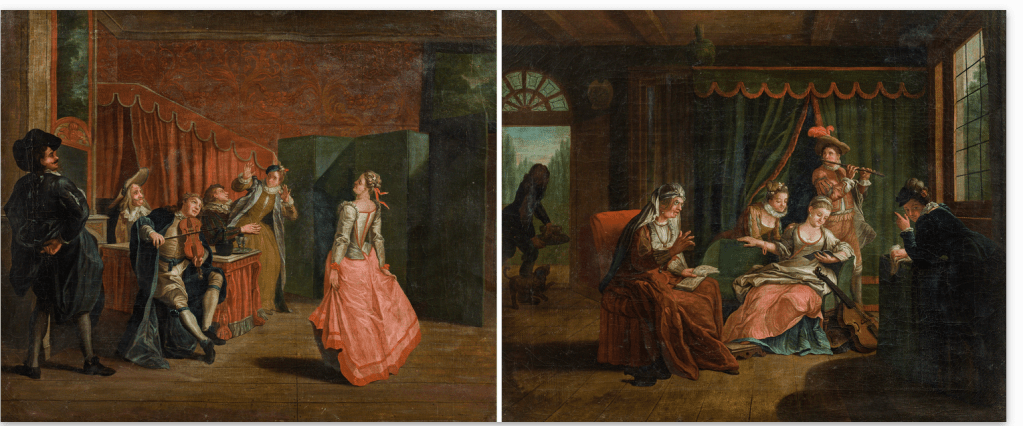

There are virtually no eighteenth-century Dutch and Flemish paintings that depict a dance lesson. It was only after an exhaustive search that I found a pendant aptly titled Music and Dance Lessons. This piece is attributed to an artist associated to the circle of the Flemish painter Jan Josef Horemans. The creator of Music and Dance Lessons remains anonymous. Jan Josef Horemans the Elder (1682-1759) is renowned for his portraits and genre scenes. Dance elements appear in several of his artworks.

Music and Dance Lessons – pendants – oil on canvas – each 47.5 x 58 cm – date unknown

Provenance private property, Austria imKinsky Auction House

In contrast to the previous examples, this version of a dance lesson is unusual. As is customary, a dance master plays the violin while a young lady follows his instructions, but the remaining figures require more explanation. Who are the two elite men who gaze closely at the woman dancing? And how to explain the astonished reaction of the other young woman, who appears to be held against her will? Do the empty wine glasses contribute to the explanation? May I leave it up to you to complete the narrative?

In the latter part of the 19th century, Dutch art and literature navigated towards a new direction. Artists inspired by the Barbizon School established the Hague School. Literature from abroad was also explored, particularly the naturalism of Emile Zola. The Dutch author and admirer of Zola, Frans Netsche (1864-1923), launched Studies naar een naaktmodel, a compilation of twelve essays in 1886. The illustrations were designed by Pieter de Josselin de Jong (1861-1906). The fifth essay, Oproer in het ballet (Riot in the ballet), describes a harsh ballet master drilling his dancers.

pen drawing – 1886 – Oproer in het ballet – an essay by Frans Netscher – DBNL -Digitale Bibliotheek voor de Nederlandse Letteren

This pen drawing evokes the images of the unparalleled French artist Degas. The dancer in the bottom right corner, resting her hands on her knees, looks familiar, much like the young dancer with her arms crossed behind her. The scene is realistic. Tired dancers, dancers sitting on benches, and dancers patiently waiting are a common sight in any dance studio at any moment in time. You can also see that the ballet master holds a long cane, traditionally used to beat the rhythm of the music or to give a dancer a ‘corrective’ shove. He has obviously drilled the group of dancers. This corps de ballet moves in harmonious unison. I cannot help but wonder whether the artist actually visited a professional rehearsal or if this drawing was inspired by an illustration from a Parisian magazine.

George Hendrik Breitner (1857-1923), a painter and photographer, was a passionate supporter of realism. Both his photos and paintings captured ordinary people in day-to-day situations. He often wandered the streets of Amsterdam, painting urban life en plein air. Breitner also created true-to-life portraits. His series of Geesje Kwak, a young woman wearing a kimono, is irresistible.

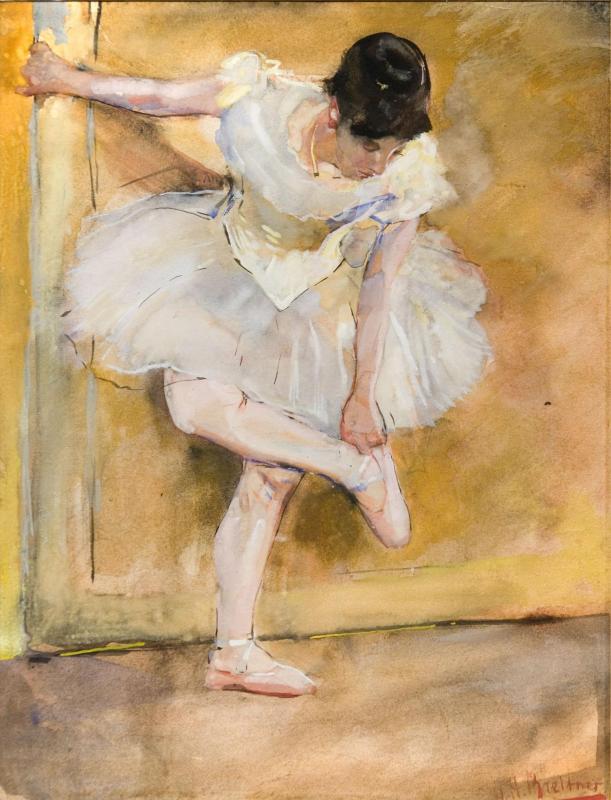

Ballerina tying her shoe – paper, aquarelle paint, 400 x 310 mm – private collection / RKD, Netherlands Institute for Art History

Step into any ballet studio, and you will find at least one ballerina lacing her shoes. The action that Breitner highlights is timeless. This ballerina clings to a door to adjust her shoes. Even though there are likely more dancers present, the artist has chosen to centre attention on just one dancer who, coincidentally, is not even dancing. I was fortunate enough to view the artwork at the Van Gogh Museum some time ago. I was enchanted by the dancer’s calmness, the beautiful yellow hue, and the familiarity of this scene.

I began this post by noting that, in the realm of Dutch and Flemish art, there are a limited number of pieces showcasing dance classes. The artworks showcased above represent the culmination of my exploratory journey. The twentieth century provides more possibilities.