The highly versatile artist Jan Miense Molenaer (1610-1668)* was a brilliant exponent of genre art. He depicted a wide variety of subjects. The only artist that could match Molenaer’s versatility was Jan Steen (1626-1679). Molenaer excelled in tavern scenes, village weddings, merry companies, representations of the five senses, school scenes, outdoor scenes, as well as portraits and family groups. Dance is a frequent feature in Molenaer’s extensive oeuvre. He was equally skilled in meticulous brushwork, which he typically employed for painting portraits and polite society, as well as a loose style frequently reserved for peasant themes.

Left – Departure of the Prodigal Son – oil on canvas – 55 cm x 66.7 cm – 1631-32 – Private Collection, RKD-Netherlands Institute for Art History

Right – Peasant Wedding – oil on wood – 36 cm x 31.5 cm – Private Collection – Auction House Lempertz, Cologne

Haarlem, renowned for its artistic inventiveness, economic prosperity, and religious tolerance in the early decades of the 17th century, attracted artists from the Southern Netherlands, thus importing the Flemish legacy to the Northern Netherlands City. Jan Miense Molenaer, who worked in Amsterdam and Haarlem for the greater part of his life, followed in the footsteps of Pieter Bruegel the Elder and the Flemish tradition. Meanwhile, he set the stage for the extraordinary Jan Steen.

One of the most common themes in Flemish art was the Wedding Dance. Bruegel’s Wedding Dance (1566) and Peasant Wedding (1567) are iconic. In Flemish art, the bride was shown sitting serenely at a table in front of a wedding cloth. Traditionally, the bride, always recognisable by her long, flowing hair, was barred from dancing. The bridegroom and the guests, however, danced and feasted merrily. In Molenaer’s painting below, about four dozen celebrants, young and old, eat, drink, dance, and make merry. The bride, adhering to tradition, remains motionless with her hands clasped. The artist particularly highlights the revellers positioned in the lower section of the canvas. The array of autumn hues enhanced with an isolated patch of blue intensifies the monochrome brown backdrop. There are three, somewhat inconspicuous, musicians playing in the centre alcove directly above the dancers. The coarse, vague depiction of these figures and other revellers in the background contrasts vividly with the well-defined foreground figures.

Peasant Wedding Feast – oil on canvas – 93 cm x 133 cm – 1659-1660 – PubHist /Private Collection

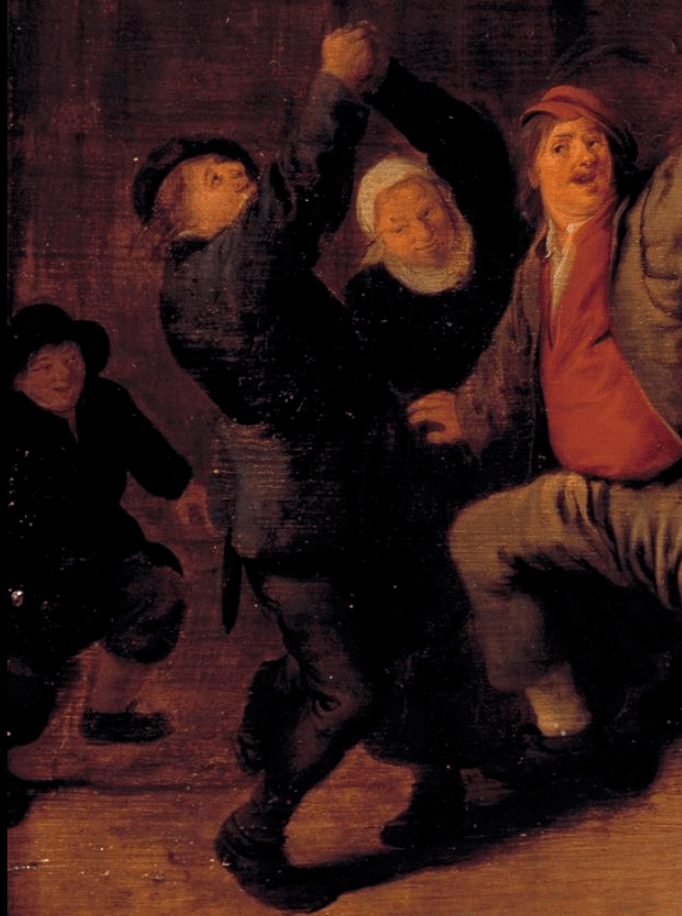

Molenaer, upholding the Flemish heritage, painted a substantial number of wedding feasts and processions. Moreover, his Peasant Wedding Feast subtly pays homage to Pieter Bruegel the Elder. In Bruegel’s masterpiece, The Wedding Dance, a dancing couple are predominately placed in the foreground. They are an absolute eye catcher. The twist of the man’s torso, together with a sharp rotary movement, distinguishes him from all the other dancers. In an equally innovative manner, Bruegel places the vivacious dancers back to back. This specific dance pose, possibly inspired by Albrecht Dürer’s celebrated Peasant Dancing Couple, is familiar from paintings by Pieter Brueghel the Younger, Jan Brueghel the Elder, Martine van Cleve, and many other Flemish artists. In Molenaer’s work, created a century after Bruegel’s composition, the lively figures are blended into a string of dancing couples. They form part of a procession of energetic, rollicking merrymakers. A close look reveals that more dancing couples are indebted to Bruegel the Elder or to the countless derivatives and imitations of works by the great Flemish master.

Right: Jan Miense Molenaer – Peasant Wedding Feast (detail) – ca.1659-60 – PubHist – Private Collection

You have very likely noticed that the Peasant Wedding Dance contains a didactic and moral message; lustfulness is openly stressed, along with dancing, drinking, and loud singing. It is equally evident that the youngsters sitting directly in front of the explicitly seductive couple are influenced by their example. The idea that children will mimic the actions of their elders from generation to generation was a familiar motif in Molenaer’s day, both in literature and art. The masterpieces of Bruegel the Elder, Jan Miense Molenaer, and, as I discussed in earlier postings, the enticingly insightful paintings by Jan Steen all feature criticism and cautions against overindulgence.

The smaller artwork, A Wedding Feast, attributed to Jan Miense Molenaer, illustrates a traditional wedding scene. The bride, following tradition, sits serenely in front of the wedding cloth. Her gaze is modestly directed downward. A musician, always present in wedding scenes, is perched on the windowsill. Only the light that passes through the window reveals his shadowy outline. He plays the bagpipe, an instrument associated with peasant life. To his right, an amorous couple is passionately entwined. Even though they are enveloped in shadows, they have attracted the attention of a meddlesome peasant woman. Her inquisitive expression, her hand movement, and her partner’s response suggest that she is offering a few pertinent comments.

Contrary to the boisterous male dancers in Peasant Wedding Feast, the rustic in A Wedding Feast appears bashful. His movements are tense and withdrawn. The backward lean, the arms clenched against the torso, the wavering hand position, the retracted head movement, and the confined leg movement lead one to presume that he is resisting his partner. Have you noticed they are not holding hands? She, on the other hand, dances with flair and lifts her legs effortlessly. The cheerful woman then needs to balance herself by resting her hand on one of the seated guests. Their dancing goes practically unnoticed by the others present. The young lad holding a beer pitcher, however, gazes enigmatically at the onlooker.

Dancing Peasants in an Inn – oil on wood – 33.5 cm x 47 cm – date unknown – Van Ham Kunstauktionen 2017

The traditional egg dance was a popular pastime in the Low Countries during the 16th and 17th centuries. Jan Miense Molenaer painted various works depicting egg dances, all set in dark, run-down taverns where card players gather around wooden tables, couples caress, and habitués drink, smoke, and make merry. In the painting above, a couple of revellers risk a frolic around the fragile egg. They hop and skip in perfect unison. The dance is all part of the evening’s fun; more often than not, the dancer clings to a jug of ale. The dim lighting makes it impossible to distinguish the characteristics of the individuals positioned in the background. However, judging by their demeanour, we can assume that the guests are more than a little tipsy.

Molenaer was not the artist to condemn human behaviour. Similar to Bruegel the Elder and Jan Steen, he offers unmistakable hints regarding moral values. The items scattered on the floor and the actions of the figures serve as clues. The significance of the ale, oysters, dispersed pipes, a wine-filled glass, and assorted beer jugs and barrels is clear. Just as the fondling, drinking, gambling, and dancing need no explanation. This wealth of hints, along with the lively chaos, disorder, and Molenaer’s charming sense of humour, typifies a genre scene from the early 17th-century genre art in Haarlem.

Festive Scene – oil on wood – 53.3 cm x 80.6 cm – ca.1650 – Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington D.C.

The brown monochrome setting serves as a backdrop for a group of revellers feasting in the local tavern. In addition to the plentiful alcohol, couples are embracing, musicians are performing, an overly enthusiastic older woman is singing, and other individuals are engaging in various vague activities. All the figures and paraphernalia harmonise with the natural colour palette, except for the breathtaking dancer. Her light attire, juxtaposed against the browns, dark reds, and blacks, highlights her vivacious locomotion. How she moves! Her partner is equally dynamic. Customarily, during the Golden Age, the movement depicted of lowly dancers is limited to a form of hopping or skipping. The dancer is often illustrated with one leg raised. This makes it difficult to determine tempo, direction, or momentum. This is not the case in Molenaer’s Festive Scene. The broad, uninhibited strides, the strong forward thrust of the body, the woman’s tense arm movements combined with the swift flow of her apron, all demonstrate the artist’s skill in conveying motion, speed, and energy on a flat surface.

Right: Pieter Bruegel the Elder – The Wedding Dance (detail of dance movement) – 1566 – Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit

It may go unnoticed, but in a dimly lit section of the tavern, behind the vivacious dancers, is another couple. Their resemblance to a dancing couple by Bruegel is remarkable. The male dancer is depicted from behind, using his raised right hand to twirl his partner. In Bruegel’s painting, Peasant Wedding, the figures are robust and vibrant. In contrast, the dancers in Molenaer’s works are depicted with a loose style, are dark, and blend into the background. Even more obscured, but nonetheless significant, is a little boy partially cropped at the edge of the canvas, mimicking the elder’s dance. There is no need for further explanation; Molenaer reminds his viewers of their moral obligations.

A gracious peasant girl tenderly clasps her partner’s hand. Perhaps the couple is softly swaying back and forth. They, in contrast to the rest of the painting, are illuminated. She, especially, stands out in her white attire. She guides the observer deeper into the artwork where musicians perform and couples amuse themselves. Her presence is remarkable. She is clearly positioned in the foreground, setting herself apart from the other figures and leading the viewer along a path of revellers. At this moment, I should point out that it was Pieter Bruegel the Elder who, in his innovative painting The Peasant Dance, positions monumentally sized peasants in the foreground. The peasants are depicted at eye level and not, as was common at the time, seen from a bird’s-eye perspective. Molenaer’s graceful dancer is not exactly monumental, but no less than Bruegel’s stupendous couple, she draws the onlooker into the painting.

The Village Inn – oil on panel – 45 cm x 68 cm – 1659 – Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

The Village Inn, created during the final decade of Molenaer’s life, immerses us in a bustling tavern. A sizeable crowd has gathered, making it easy to overlook the bride sitting beneath the customary wedding cloth. Several guests gaze confidently ‘beyond’ the artwork, inviting everyone to participate in this celebratory event. The characters, aside from a devout woman sternly regarding the observer, are joyful. In this characteristic genre scene, Molenaer features individuals from different social strata. The men serving the beer are simple folk, as are the amorous couple in the centre and the numerous guests assembled around the table. They create a notable contrast with the affluent dancing pair. Observe their impeccable dress: pay attention to the rhythmically sewn buttons on the man’s breeches, the delicately adorned shoes, and the luxurious materials. No less interesting is that the woman stares at the flirting couple. Is this an intentional hint? A little gentle mockery? You may wonder what she is contemplating and what the artist intends to convey.

This humorous artwork interweaves society as a whole. Elements of everyday life, faith, and ethics are continuously examined and debated in a genuine, comedic, and exaggerated fashion without blame or judgment. The same description could apply to the work of Jan Steen. Steen resided in Haarlem from 1660 to 1670 and would have been familiar with Jan Miense Molenaer’s work and Haarlem’s Flemish tradition. Jan Miense Molenaer is a vital link between the Flemish School and Jan Steen. His oeuvre is creative, innovative, and impressive. This major artist of the Dutch Golden Age amazes us, time and again, with fascinating dance images.

* The surname Molenaer, which translates to ‘miller’, is a frequently encountered name in the Netherlands. Jan Miense Molenaer had two brothers who were also artists; Bartholomeus Molenaer (1618-1650) was recognized for his genre works, while Nicolaes (Klaes) Molenaer (1626/29 – 1676) became renowned as a landscape artist. Other Molenaers active in Haarlem included Jan Molenaer, Jan Jacobsz. Molenaer (1654 – ca. 1684/90), and Jan Molenaer II (1654/58 – around 1700). There is minimal biographical information available on the last three artists. All of them worked in Haarlem, created genre paintings, and to the best of our knowledge, were not related to Jan Miense Molenaer.