Cornelis Dusart (1660-1704), who resided in Haarlem for the majority of his life, was one of the most prominent genre artists during the last quarter of the 17th century. Dusart was Adriaen van Ostade’s last student, taking over his master’s studio in 1685. He excelled in painting, drawing, and printmaking. Dusart’s paintings presented a convivial rendering of peasant life. Dancing couples and solo dancers often featured his works. Similarly, his drawings and etchings frequently included dancing figures and performers. In the previous post, I looked at various dance figures in Dusart’s paintings. In this post, we’ll delve deeper into the dance figures showcased in his prints and etchings, starting with his iconic piece, The Large Village Fair.

The village fair was a recurrent motif in the 16th and 17th centuries. The earliest scenes showing peasant celebrations were by the German artists Hans Sebald Beham and Erhard Schön. Flemish artists soon adopted the rural motif. The peasant scenes by Pieter Bruegel are exemplary. Other Flemish artists, Marten van Cleve, Pieter Balten, Gillis Mostaert, and Pieter Brueghel the Younger, to name but a few, continued and developed the widespread practice. Adriaen van Ostade’s etching Dance under the Trellis, discussed in a previous post, depicts rustic merrymaking in a village street. Dusart, following van Ostade’s example, composed a village scene with dancing figures and a wealth of characters, each with their own unique story.

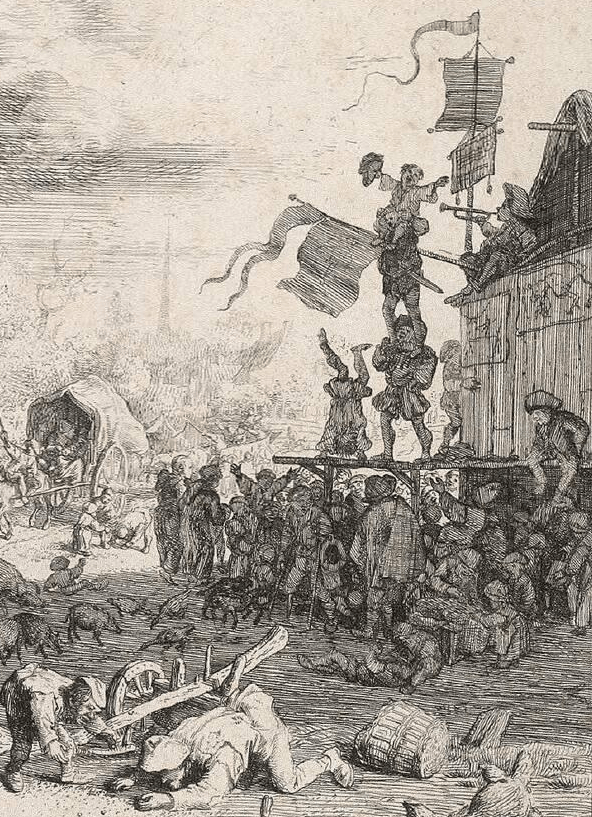

Dusart’s village fair is booming with activity. There are dancers, acrobats, pigs, chickens, a quack doctor, children playing, a horse-drawn carriage, and a myriad of revellers. One reveller stands in the tavern doorway cheerfully holding a jug of ale. More revellers look through the tavern window watching the merriment taking place on the village square.

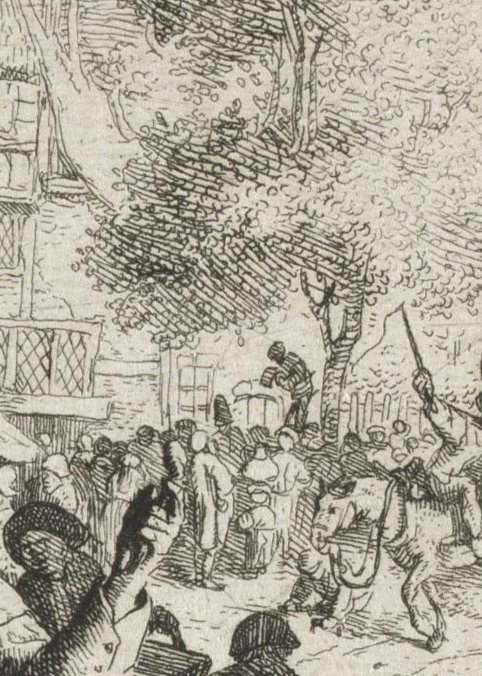

Before turning to the dancers, permit me to glance at other forms of entertainment illustrated at this village celebration. For starters, take a moment to look at the performance taking place under the parasol. Two ornately dressed actors amuse their audience with tricks and antics. On the right side of the print, a troupe of acrobats perform amazing feats. The tower created by the three adventurous performers dazzles the audience, as does the tumbler standing on his head. And all the while a harlequin-like figure sounds his trumpet. The crowd gathered at the foot of the wooden stage is diverse: village people of all ages take pleasure in a day off from their everyday grind. But what to make of the bungling fellow creeping around the corner of the decor? A stagehand, perhaps, or an inquisitive villager. This theatrical vignette is interesting from a historical perspective. The artist presents an authentic picture of travelling performers and their makeshift stages. There is a third theatrical moment farther back. A quack doctor has installed himself under a lofty tree, enticing his spectators to purchase his dubious merchandise.

Left: detail showing the performance of two players under a parasol – Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art Cornell University

Centre: detail showing acrobats on a makeshift stage – Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art Cornell University

Right: detail showing quack and his audience – The Cleveland Museum of Art

The Large Village Fair, Dusart’s most substantial etching, highlights a group of dancing rustics. The capering trio directly commands attention. The dancing couple alongside assumes a secondary role. All the dancers are exaggerated. Their gestures and grimaces are practically caricatural. They are positioned in a zone of light. The foreground is uncluttered, allowing a detailed and distinct view. The light effect is further accentuated by the dimmer lower border where chickens, a basket, and a child rest in the shadows. And finally, the figures and the action immediately behind them are darker and far less detailed.

The threesome performs a curious dance. Many revellers are in awe. Note the surprise on the face of the child playing with the hobby horse, and of the woman peering under the dancer’s uplifted arms. What has captured their attention? Perhaps it is the unwavering woman tugging on one man and clasping the other. Perhaps the man on our left, who, despite stepping forward, remains hesitant to heed the woman. Or perhaps it is the cheerful peasant dancing vivaciously to the fiddler’s lively tune. He is depicted in the traditional 17th-century style, with bent knees, raised legs, and inclined posture. We can merely guess how these rustics moved. However, this trio is certainly not performing a typical country dance. You might indeed wonder if the three are actually dancing or if the peasant woman is trying to convince her intoxicated companions to go home.

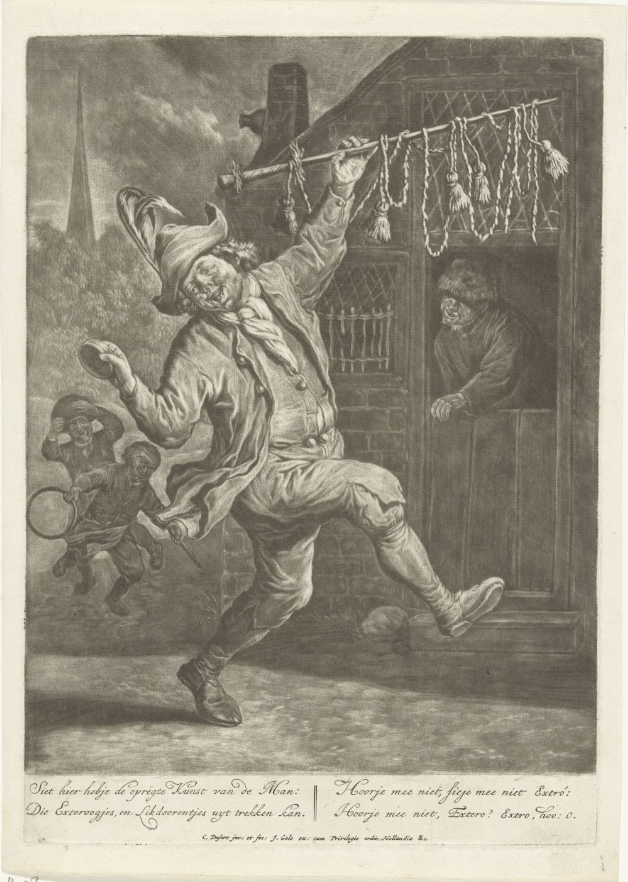

Dusart created numerous smaller genre drawings and etchings. The range of subjects is extensive. There are family and tavern scenes, lovers, peasant couples, festivities, and a variety of professions. One of the most distinctive is a delightful illustration of a corn cutter, complete with a verse promoting his remedial skills. The jolly bearer of corn relief dances in the village street holding a tambour stick adorned with a cord of brushes. As children playfully chase after him, a satisfied or potential customer, standing in the doorway of a cottage, smiles at the impromptu dancer.

Left: The Corn Cutter – mezzotint – height 253mm x width 180mm – circa 1700 – Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

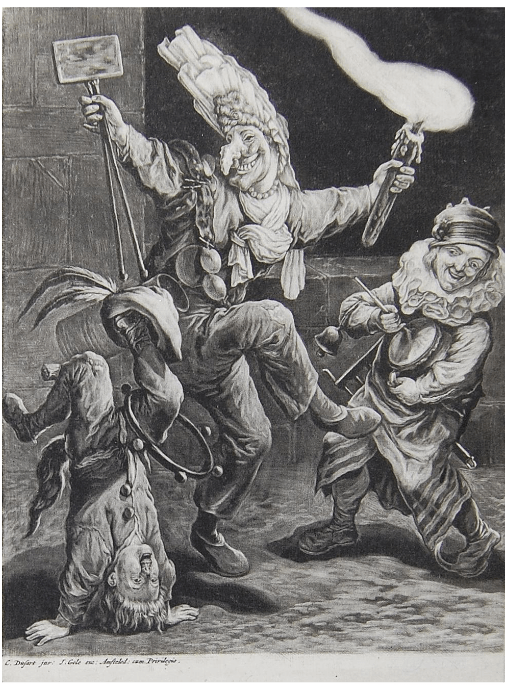

Right: The Months, February – mezzotint/paper – height 216mm x width 155 mm – published between 1675 – 1704 – The British Museum

The carnivalesque scene, on the right, represents the month of February from a series of prints illustrating the months of the year. The three merrymakers are clad in their finest carnival attire. They are dazzling, agile, and unquestionably theatrical. One boy performs a handstand, while the other youngster plays a rommelpot (a friction drum). The centre figure is disguised in an elaborate clownesque costume. His grotesque mask and aristocratically inspired wig are not without a touch of satire. This burlesque figure, even more than the previous figures discussed in this post, is a sumptuous caricature. Satirical characters and caricatural figures are common in Dusart’s prints and etchings.

It is impossible to overlook the striking similarities between the dance actions of the jester and the corn cutter. The characters’ movements are portrayed in the manner that artists of The Low Countries traditionally portrayed non-aristocratic dance. Dusart, in the footsteps of Bruegel the Elder, Adriaen van Ostade, Jan Steen, and David Teniers, depicts the dancing figure as robust and uncouth. Characteristically, the figure has a bowed back, slightly bent knees, one leg raised, feet turned inward, and free-flowing arms. Keeping these traits in mind, cast your eyes at the following prints created to celebrate the victory of William III, King of England and Prince of Orange, over the French troops of Louis XIV at the gates of Namur, September 1695. The prints are part of the series “General Gladness about the Siege of Namur.”

These prints are part of a series of eight prints created following the conquest of Namur, “General gladness about the siege of Namur.” September 1695 – Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

The Happy Patriot – mezzotint/ paper – height 260mm x width 180 – 1695

Dancing Pair – mezzotint and engraving/paper – height 260mm x width 180 mm – 1695

The Woman of the Orange Faction – mezzotint and engraving/ paper – height 260mm x width 185mm – 1695

These three entertaining prints reflect the thrill of victory. The happy patriot dances exuberantly, clenching an empty wine glass in one hand and his hat in the other. The text beneath the print reveals that now that the war has ended, he can no longer pilfer the French wine. The following print shows a dancing pair engrossed in a lustful encounter. That the drunken sailor clings to a bottle of beer is understandable, but what to make of the pouch of coins perched on the harlot’s head? The contents of the conspicuous purse, no doubt, clarify their unbridled passion. And finally, a practically bare-breasted resolute partisan moves with irrepressible vitality. The orange enthusiast fervently flutters a flag while ecstatically flaunting a patriotic pamphlet.

The various figures, however different in personality and profession, are painted in the traditional low-life manner. They are hefty, perform unpredictable movements, and impress with their capriciousness. Dusart has exaggerated both movements and facial expression, transforming low-life figures into comical caricatures.

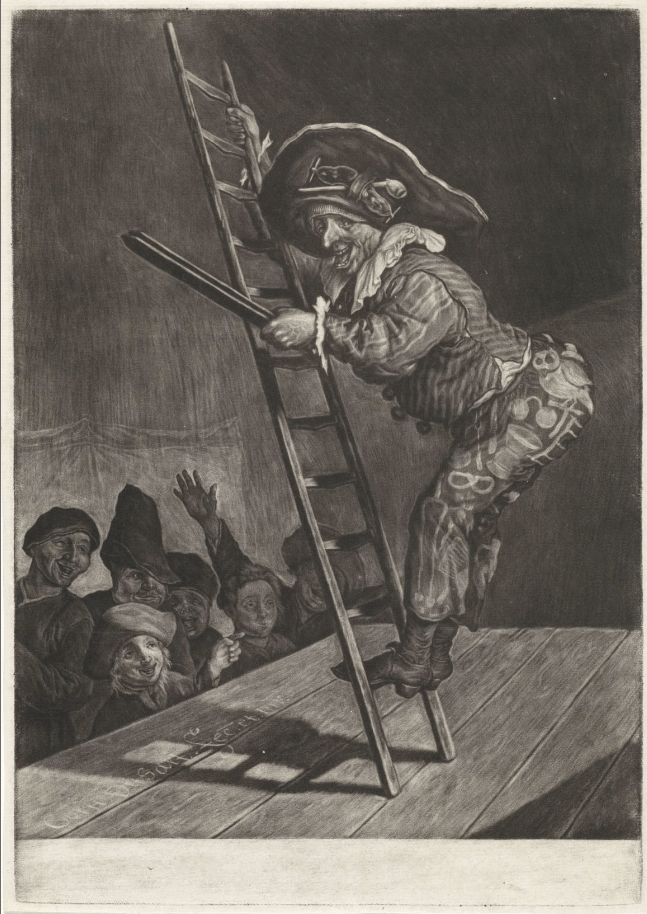

I do not wish to leave Dusart without presenting an image of the popular theatrical figure, Harlequin. The print depicts the commedia dell’arte figure balancing on an unsupported ladder. Some members of the audience are mesmerised; others watch with apprehension. Furthermore, Dusart has meticulously embellished Harlequin’s trousers. There is a delightful drawing of an owl, as well as a wine glass and a variety of household utensils. Yet, to my mind, the most stunning of all is Harlequin’s mischievous glance. He virtually entices the viewer into the performance. This playful image captures Dusart’s creativity, theatricality, and his unwavering sense of humour.