Adriaen van Ostade (1610-1685), a major artist of the Dutch Golden Age, was highly productive. Over eight hundred of his paintings are extant. He was also a renowned printmaker, second only to Rembrandt van Rijn. Van Ostade’s paintings and prints were in high demand. His early work, discussed in the previous post, depicts scraggy peasants in every conceivable form of loutish behaviour, revelling in decrepit taverns and barns. Whether the peasants were drinking, frolicking, flirting, smoking, fighting, making music, or dancing, van Ostade set the scene in a gloomy interior with subdued light falling primarily on the principal characters. The outer borders of the canvas invariably have a monochrome brown hue. The peasants are stubby and ungainly. Their coarse, even grotesque, appearance is virtually caricatural.

After 1640, Van Ostade embraced a brighter palette. His style, influenced by the Leiden School of Fijnschilders, acquired refinement. The rustics lost their grotesque qualities, lost their wild gestures, mellowed their strong exaggerated emotions, and gained in propriety to transform into amiable peasants merrymaking in pleasant surroundings.

Compared to the tavern illustrated in Interior with Peasants Dancing, the inn presented in Merrymakers in an Inn is comfortable and orderly. The figures, the furnishings, the little doll, and even the embroidery of the cushion on which the man with the red cap is sitting are meticulously painted. You only need to gaze through the stained-glass windows to see a beautifully detailed pastoral scene. Van Ostade harmoniously blends warm and cool colours for the figures in the foreground. The background, the upper walls, and the ceiling are shaded in brown and green hues. A bright light falls on a short, middle-aged woman and her cordial partner. A quick glance around the room reveals that most of the other figures relate to the pair, despite their drinking and chatting. But why are these dancers the centre of attention? The props scattered over the floor offer an explanation. The knocked-over bench in the foreground and the pair of cast-away slippers make you wonder if the rustic suddenly broke into a spirited dance when the musician played a lively tune. Did he catch the woman by surprise? His partner appears rather nonchalant. She stands upright, moves cautiously, and gives the man a rather perceptive gaze. He, on the contrary, dances enthusiastically, swings his feathered cap backwards, and bows politely. Are we witnessing an impromptu dance between an innkeeper and a slightly inebriated tavern guest?

The woman’s radiant white cap is an eye-catcher. The only other bright white features are the little girl’s bonnet and the blouse of the younger woman who is being caressed by her companion. Van Ostade uses the white hue sparingly and with reason. These three female figures—the playful young girl, the budding young maiden, and the more experienced, mature woman—symbolise the three phases of life. Less obvious is the reference to children mimicking adult behaviour. Dutch 17th century artworks frequently contained a humanistic or moralistic connotation. Take, for example, the youngster drinking from a beer stein. You can discover him directly behind the male dancer. Further forward, a young boy, imitating his elders, dances with his dog, while the girl lovingly cares for her doll.

Upon first glance, Peasants Dancing in a Tavern depicts a jovial scene of a 17th-century tavern. Among the guests are two vigorously dancing couples. The peasant dancers, as traditionally painted, have a stooped carriage and dance robustly in an unpolished manner. The movements of the front couple are clearly visible. The impetuous fellow in the blue jacket characteristically curves his torso forward and throws one leg impulsively into the air as he swiftly rotates away from his partner. He and the other rustic dancers resemble the dancers in Pieter Bruegel’s The Wedding Dance.

However, don’t allow first impressions to fool you. The peasants obviously enjoy the wine; many are flushed and some are totally dazed. Wine jugs abound, just as do the many haphazardly strewn pipes. Wine and dancing, van Ostade warns, leads to promiscuity; small wonder that the tipsy man is practically halfway up the stairs. And what to make of the playing cards scattered around the room?This is a direct allusion to the evils of gambling. And finally, van Ostade highlights the dancing couples. Dance was, under no circumstances, considered a virtue. Even though the setting of this jovial scene seems comfortable and friendly, Peasants Dancing at a Tavern cautions against debauchery.

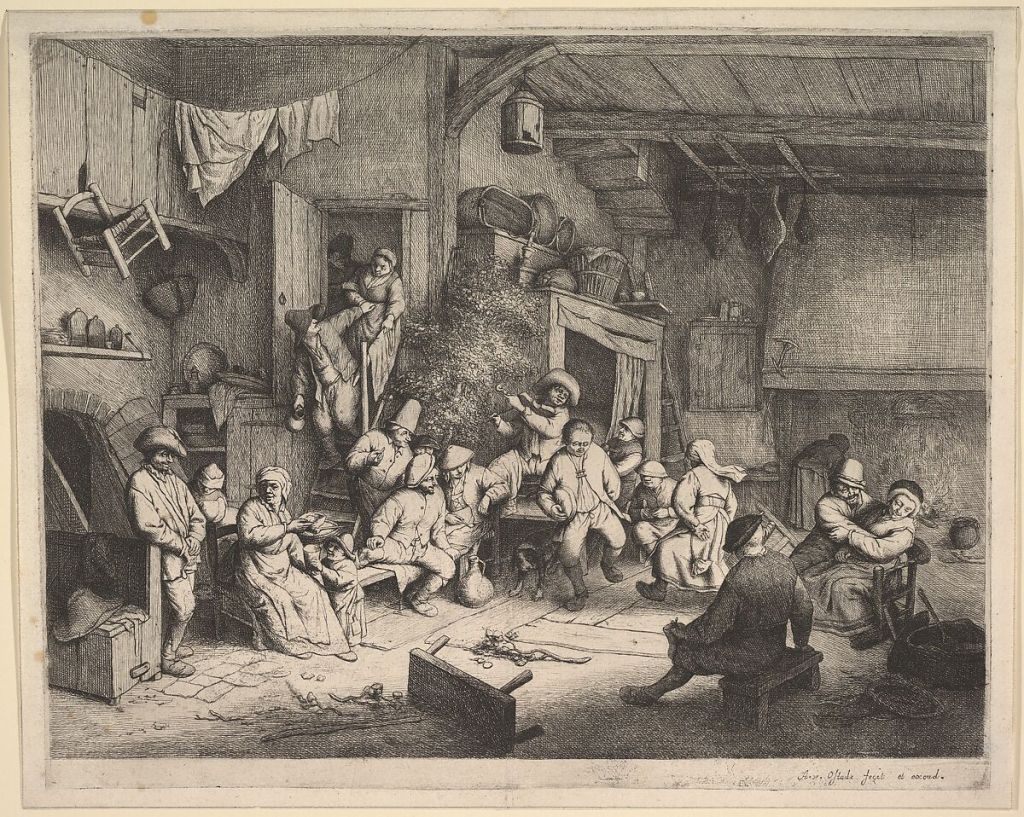

With most of the Dutch artists, etching was a subordinate accomplishment, and their work on copper is but a less interesting reflection of their work on canvas. This cannot be said of Ostade. As with Rembrandt, his etched work is the complement, rather than a supplement merely, of his painting.

Dutch Etchings of the Seventeenth Century – Laurence Binyon, London 1895 – page 21

The etching, The Dance at the Inn, is a humorous genre piece. The homely touches — washing hanging on a line, stacked baskets, pots, and pans — are all rendered realistically and with painstaking detail. As entertaining as this etching may be, it still contains a word of warning. The rustic folk drink, smoke, flirt, embrace, and dance. And that listless man on the bench is surely the personification of Sloth. (1)

During van Ostade’s lifetime, his etchings were issued in limited numbers. In the 18th century, a French publisher acquired the original plates, who subsequently reissued them to be widely circulated. It’s highly likely that William Hogarth, the notable English artist specialising in depicting scenes of lower-class life, could have come across and been influenced by Van Ostade’s engravings. The impact of the Dutch artist is especially apparent in the tavern scene print of A Rake’s Progress. (2) In turn, Hogarth’s work inspired Ninette de Valois, founder of the Royal Ballet, to choreograph the dramatic ballet The Rake’s Progress. (3)

Even before Bruegel the Elder, village scenes were a popular theme. This tradition carried on well into the 17th century. Van Ostade’s delightful etching Dance under the Trellis presents rustic merrymaking in a village street. Peasants in tattered clothing play, drink, lounge, listen to music, and enjoy themselves on what appears to be a festive day or market day. There is also a large pig eating grass, a man relieving himself, children playing, and a musician, positioned on a pedestal, who plays the flute and beats his drum. His jolly tune encourages the folk carousing under the trellis to a spontaneous dance.

It is difficult to see how many people are dancing. The most striking dancer, however, is riveting. Characteristically, this peasant dancer displays a slanted posture, has a bent back, his knees are slightly bent, has one leg raised, and his feet turned inwards. His brash manner, his asymmetrically extended arms, and his complete lack of poise and aplomb are typical of the manner in which the 17th-century Dutch and Flemish artists depicted peasant dancing.

No less engaging are the leading dancers in Peasants Carousing and Dancing outside an Inn. This amiable couple jog from one foot to the other. They are accompanied by a violinist and cheered on by a very jolly man raising a glass of alcohol. The dancers are brightly illuminated, which contrasts with the more subdued tones used for the other figures. The woman’s white cap and, to a lesser extent, her off-white apron make her, similar to Merrymakers in an Inn, the most pronounced figure in the painting. Is she the innkeeper revelling? Her mature age does not inhibit her from actively throwing her legs in the air. She and her partner perform their improvised dance to the delight of the onlookers. Just behind them is a second dancing couple. The bearing and actions of both dancing couples are, as pointed out earlier, indebted to the dance figures of Pieter Bruegel the Elder and his peers.

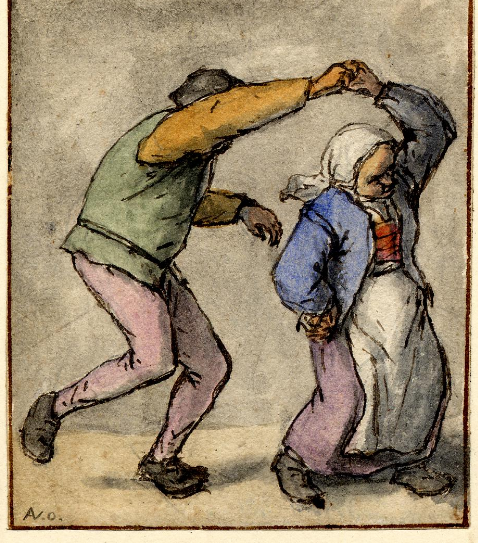

A post discussing dance in Adriaen van Ostade’s work should feature the following preliminary sketches, which are housed in The British Museum. Van Ostade’s skilful drawings, though the essence of simplicity, capture a sense of rhythm and momentum. With a little imagination, the onlooker can envision the dancers in motion.

- Couple Dancing – c. 1659-1670 – 134mm x 154mm – British Museum

- Man Dancing – c. 1670-1685 – 78mm x 46mm – British Museum

- Couple Dancing – c. 1670-1685 – 88mm x 76mm – British Museum

Adriaen van Ostade resided and worked in Haarlem his entire lifespan. He left behind an impressive legacy. His paintings are not only displayed in museums around the globe, but he was also a motivating tutor. Some of his pupils included Richard Brakenburgh, Cornelis Pietersz Bega, Cornelis Dusart, his brother Isaac van Ostade, and, possibly, the famous Jan Steen.

- The etching The Dance at the Inn has a counterpart. The painting, titled Villagers Merrymaking at an Inn , can be seen at the Toledo Museum of Art, Spain.

- I am grateful to the Museum of New Zealand, Te Papa Tongarewa, Wellington, for drawing my attention to the connection between Adriaen van Ostade and William Hogarth. With particular thanks to David Maskill, writer of the article, published Art at Te Papa, Te Papa Press, Wellington, 2009.

- Ninette de Valois choreographed the ballet The Rake’s Progress in 1935 for the Sadler’s Wells Ballet (Later known as the Royal Ballet).