The longer you ponder over the nebulous illustration shown below, the more details come to the fore. At first glance, the image is misty. The chalk sketch is rendered in barely distinguishable strokes. Gradually, a gracious apparition materialises. Dancing figure, to the left, by Matthijs Maris (1839-1917), slowly discloses a lyrical female dancer wrapped in diaphanous drapes. Her delicately outlined silhouette emerges from within the haze. The subdued lines reveal that the figure floats effortlessly. The dancer, not dissimilar to muses represented on Greek or Hellenistic reliefs, has rotated her torso towards the back as she holds a musical instrument, possibly a tambourine, in her uplifted hands.

Maris was initially a member of the Hague School. With only relative success, he abandoned realism to develop a unique style. From the 1880s on, he created a series of opaque paintings where haunting figures are shrouded in mist. The figures are not readily distinguishable, but as the viewer’s eyes adjust to the unspecific brownish canvas, Maris unveils a vaporous vision.

Dance rarely inspired Maris; a four-panel dressing screen represents the magnificent exception. When the artist discovered a gold-coloured wooden screen in a Parisian art gallery, he cut away the old fabric and stretched a new canvas onto the frame, to create an original composition comprising of four full-length dancing figures. Each of the dancers, draped in transparent chiffon, owes their ease and fragility to Dancing figure, to the left. The outer nymphs are turned in the direction of the viewer, gently rotating their bare torsos towards the centre panels. The suggestive curves of these lyrical, light-footed dancers are simultaneously serene and sensual, notably reminiscent of classical reliefs. They, like their companions, carry a musical instrument. The centre figures are the more vigorous dancers. The dancer, with her back to the audience, is captured in mid-jump. Her fleeting diaphanous robe, just like her flowing locks, highlight her abandon. Her counterpart is equally graceful. Maris leaves you wondering if the delicate spirit is descending from a jump or turning on the spot. His four nymphs, however, a unison in dress, colour, height, and background, form a frolicsome quartet of graciously alluring dancers.

height 65.5 cm × width 155 cm × height 50 cm × width 162 cm – Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Where Matthijs Maris rarely found inspiration in the dance, Pieter Cornelis de Moor (1866-1953) painter, illustrator and etcher was repeatedly drawn to the art of movement. Born in Rotterdam, de Moor after his initial study in his home city, studied with Pierre Cécile Puvis de Chavannes, the French artist celebrated for his Symbolist work.

The Netherlands Art Institute has a number of dance images by de Moor on their database. He exclusively paints female dancers. They are invariably encountered in an indiscernible setting. The consistently slender dancer is dressed in a transparent gown or clad in flowing materials. Her bare legs are only covered by the most flimsy of fabrics, and her feet are, with an occasional exception, not obstructed by any footwear. In most paintings, the dancer manoeuvres a voluminous scarf. Interesting is that none of the dancers jump, spring, or otherwise leave the floor. Moreover, the dancers cast their eyes either downwards or turn their faces slightly sideways, avoiding contact with the viewer.

De Moor uses a loose brush stroke. This, together with the circular motion of the veils/scarves, gives the impression of continual movement. That sense of motion is most pronounced in The Three Graces, where de Moor draws specific attention to the delicate physical curvature of the goddesses in blue. The revealingly clad dancers in Two Dancers tell a different narrative. These voluptuous dancers, flaunting their substantial scarves, are most likely professional performers dancing, on what appears to be, a stage.

Left: The Three Graces – watercolour – 60 cm x 73.5 cm – Galerie Nieuw Schoten, Haarlem

Right: Two Dancers – black and coloured chalk – 24 cm x 29.5 cm – Hein A.M. Klaver Kunsthandel, Baarn

An exception to de Moor’s customary approach is A Dancing Couple, where a poetic male dancer performs a romantic duet with his featherweight partner. He attentively supports her back, allowing the fragile figure to flow into a gentle elongated curve. She, as many of the artist’s other dancers, wears a free-flowing delicately transparent gown. And, of course, you have noticed the tiny red shoes that are laced with ribbons. These resemble soft ballet shoes. The couple’s costumes and prearranged choreographic positioning suggest that they are professional performers.

Left: A Dancing Couple – watercolour and gouache on paper – 28 cm x 15.4 cm Simonis & Buunk/ Christie’s

Right: Dancer – oil on canvas – 100cm x 71 cm – 1910 – Studio 2000 Kunsthandel, Blaricum

The costumes, headdress, and attributes leave no doubt that the figure portrayed in the half-portrait, Dancer, is definitely a professional performer. The portrait focuses on the back, face, and headdress of an intriguing exotic artist. There are no actual dance movements to be seen. The background, typically of de Moor, is obscure. It fascinates me to see how the artist has painted the dancer’s back and hair with a loose brushstroke and rendered her face, together with her hands and jewels, with precision. The refined facial features have a velvety finesse. The intricate jewels decorating her opulent headdress are meticulous, not to mention the detail and accuracy of the hands and even the nails. This juxtaposition of clarity and haziness, of loose and detailed brushwork, and the sheer beauty of the mysterious subject forge a riveting artwork.

The name Willem Arondéus (1894–1943) may not ring a bell. Not surprisingly. He gained little fame as an artist, though he worked arduously as an artist, illustrator, and carpet weaver. He was also an author, publishing Matthijs Maris: The Tragedy of the Dream in 1939. And significantly, he is commemorated for his courageous role in the Dutch resistance during the Second World War.

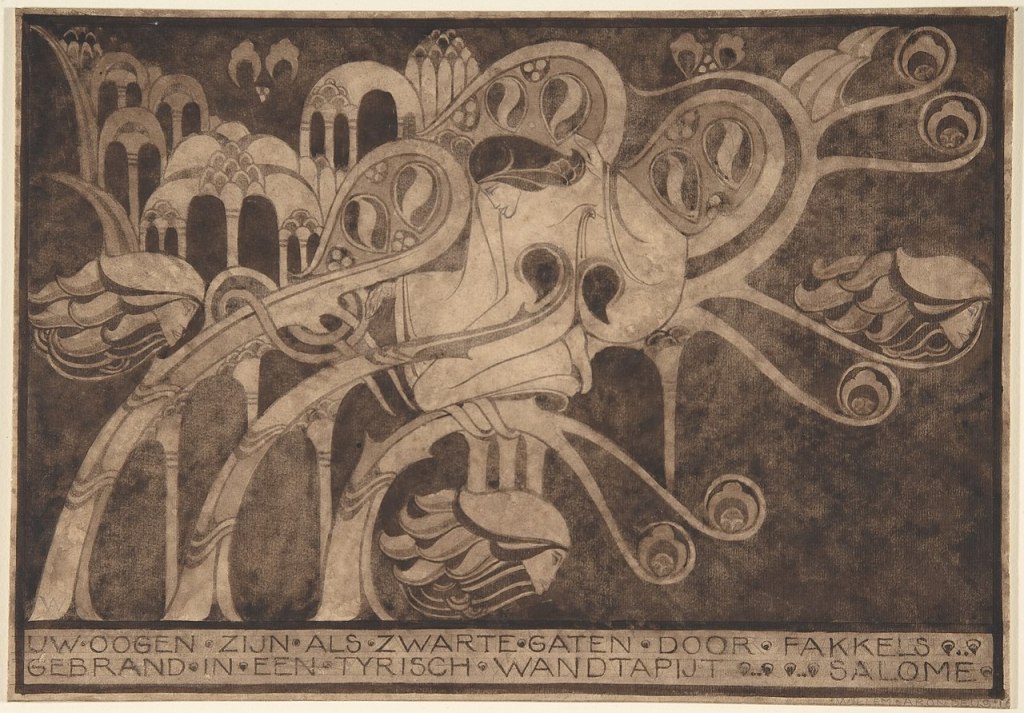

The following image does not strictly fall into the dance category. This intricate composition presents the young Salome entwined within a meandering vine, whose blossoming buds yield the decapitated head of John the Baptist. Every line is curved. Only the faces have a slightly angular appearance. The static domes planted in the background contrast with the gyrations of the mystifying vine, whose tendrils overlap, interlace, and swirl incessantly. Salome may not physically dance but, embedded amidst a roaming vine, she remains in perpetual motion.

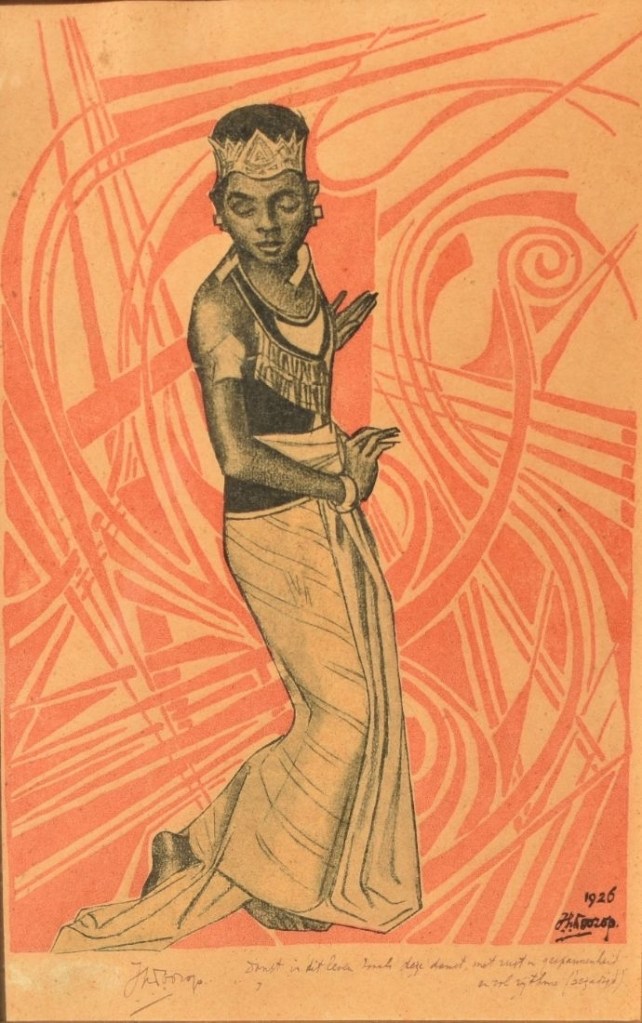

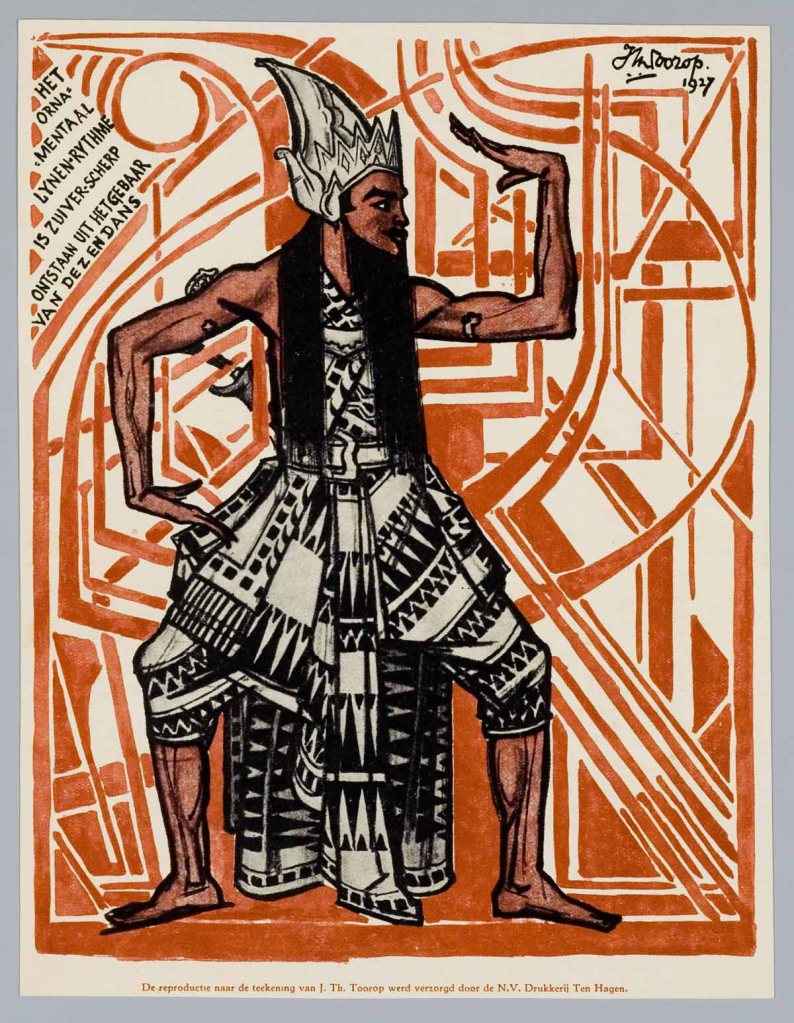

Jan Toorop (1858-1928) is equally celebrated for his flowing art nouveau images, his austere works, and his symbolic compositions. Toorop, who was born in Central Java, fused his Asian and European cultural heritage to develop a unique artistic language. There are few actual dance images in his oeuvre, but his cross-cultural works, even though not readily classified as dance, display a movement quality that is second to none. A prime example is the masterly work, O Grave, where is thy Victory?; Toorop highlights two angels (seraph) floating, in exquisite harmony, above the grave. The illustrator, Toorop, designed two posters that revisited his Asian roots. I have taken the liberty of adding a third poster. Though not actually a dancer, the figure portrayed on the poster is formidable. Her forward thrust distinguishes itself dramatically from the two statuesque figures bordering the sideline.

Left: Javanese Dancer Serimpi – 20 cm x 13 cm – 1926 – MutualArt.

Centre: Jan Toorop – Asian Dancer – paper – 1927 – Information RKD – whereabouts unknown

Right: poster for the play Pandorra – 114 cm x 85 cm – 1918 – Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam

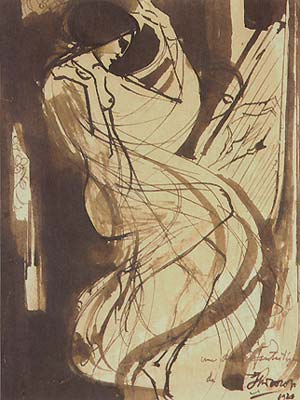

Apart from a delightful drawing of three young girls dancing the polka and a drawing of a couple dancing between flames, I found an intriguing drawing with the enigmatic title Une Danse Fantastique. The dancer’s curved position, her inbound demeanour, and her emphatic arm placement clearly suggest that this is a modern expressionistic dancer. In the early part of the 20th century, the American dancer Isadora Duncan graced the European stages. A pose of this kind could clearly be associated with Duncan, but just as easily be inspired by the German ausdruckstanz.

The dancer practically occupies the entire page. Toorop depicts a bare-breasted dancer in a weighed down, curved pose. The contours of her body, basically an s-form, reveal themselves through the transparent robe. The outline of her bent legs is clearly visible. Hidden half-way behind the curtain is a second figure. We can only see a narrow section of her face. It took me a long time to realise that this figure is playing a harp. On the other side of the dancer is a figure which I still cannot unravel.

Toorop’s dancer is not a light, aerial dancer. In Une Danse Fantastique, beauty, in the sense of costumes, setting, and attributes, is not of the essence. This passionate dancer is neither graceful nor alluring. Rather, Toorop transforms unadorned dynamic movement onto a two-dimensional plane using only a diversity of lines and forms. That, and the ‘simplicity’ of the monochromatic colour scheme, allow the viewer to contemplate if Toorop visualised a fantastic dancer or a fantastical dancer.