In an earlier post, I wrote that Theo van Doesburg (1883-1931), the driving force behind the art movement De Stijl, was a man of immense talent. He was a writer, painter, designer, performance artist, and photographer. Van Doesburg was also fascinated by architecture and envisioned a world where the individual would not be a mere spectator, gazing at a painting, but would become an active participant, fully embraced within an artwork. This post, the seventh in a series discussing dance images by artists of De Stijl, explores more dance and dance-related works by Van Doesburg before turning to three artists associated with or inspired by De Stijl.

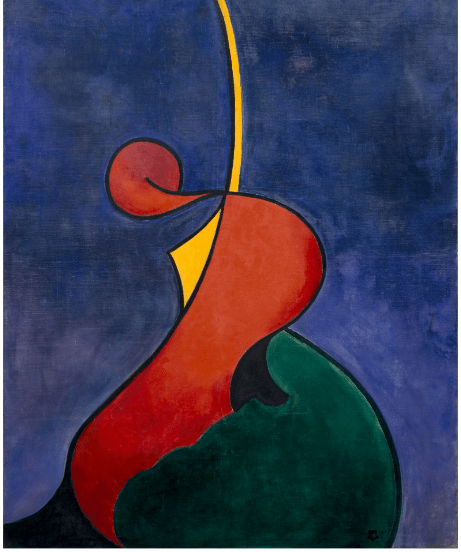

The bold work, Mouvement héroïque, created just before the founding of the art movement De Stijl (1917), displays a clarity of line, striking colours and a unique curvilinear shape, moulding an abstract form that brings to mind Henri Matisse’s masterpiece, La Danse. Van Doesburg was well acquainted with the painting, discussing the work of Matisse and publishing an illustration of La Danse in a 1917 publication.(1) Over the years, Mouvement héroïque has been exhibited under various titles, including Danse heroïque, La Danse, and from 1983, as a result of a revelatory article, gained the suffix La Danse.

Whether the spectacular conglomeration of solid shapes, vivid colours, and daring spatial design goes by the label of dance or movement is not significant. Mouvement héroïque is kinetic art. The dominant red shape emerging from a dark green encirclement directly addresses the viewer, who, in turn, cannot escape the upward thrust of the narrow, yet eye-catching, yellow beam. The powerful red and yellow forms gain greater prominence being sharply contrasted by the ambiguous, demure background. Van Doesburg confided to an old friend that he ‘has poured out years of suppressed life’ into this work. (2)

For the record, Theo van Doesburg was not primarily interested in creating autonomous art. Rather, he focused on an ideal art form that embraced the individual. Photography offered the artist/innovator an opportunity to explore the simultaneity of movement in time. In these photographs, the so-called simultaneous portraits, coloured planes, the individual, and space coexist.

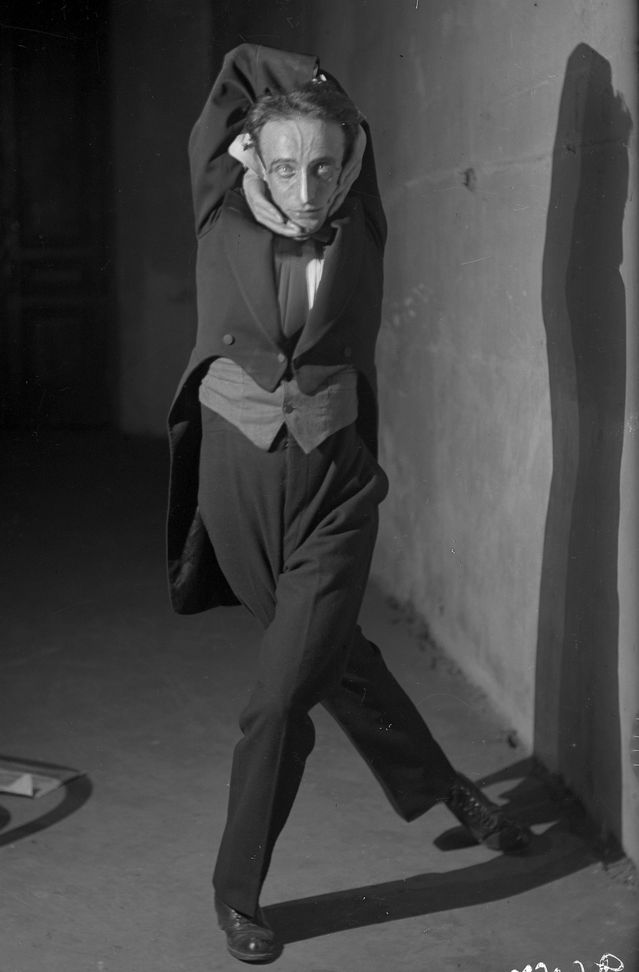

Theo van Doesburg – Simultaneous portrait of Valentin Parnakh (Parnac) in the dance Epopée (1925) – images from RKD Netherlands Institute for Art History

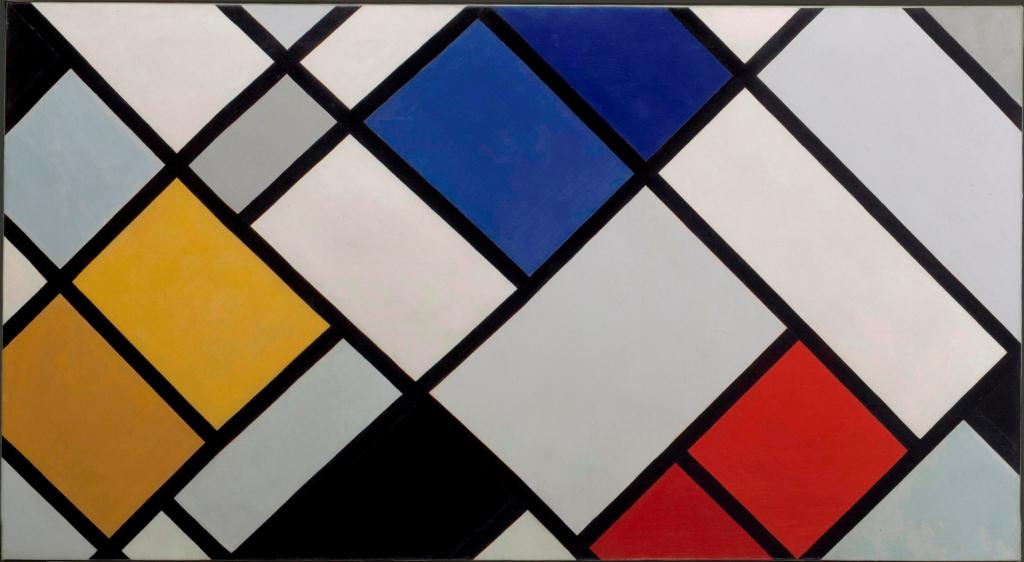

The Russian artist, writer, musician, and eccentric dancer, Valentine Parnakh (Parnac), worked with the leading stage director, Vsevolod Meyerhold. The first of the above photos shows Parnakh posing in an ‘eccentric pose’ indicative of his exceptionally avant-garde dance-style. The next two photos, taken by van Doesburg in 1925, display a practically identical pose. The artist experimented with double exposure and montage, merging the dancer and abstract painting, Counter-Composition of Dissonants XVI, into a unified whole. The left photo shows vague oblique lines and shapes superimposed onto the dancer. In the second exposure, the dancer and painting simultaneously ‘blend’; the dancer is draped with diagonal shapes and lines. The interaction between the fore and background is inconclusive, just as the distinction between space, artwork, and individual; the dancer is virtually wrapped within the painting.

A brief detour: from around 1924 Theo van Doesburg painted a series of Contra-composities (Counter-compositions) as a rebellious response to Piet Mondrian’s inflexible insistence on the exclusive use of horizontal and vertical orientations. Theo van Doesburg implemented the use of the diagonal orientation, which he designated as Elementarism. This, to Mondrian’s mind, represented a betrayal of the distinctive vision of De Stijl. Mondrian promptly discontinued his connection with the De Stijl group.

Counter-composition of Dissonants XVI was also the setting for a series of photographs of Kamares, a pseudonym for Willy van Aggelen, a dancer, writer, and journalist. Dressed in a black flowing robe and holding castanets, this multi-talented artist assumes a typical Spanish pose, harmoniously following the diagonal lines of the painting behind her. It is intriguing that van Doesburg intended the Counter-composition to be hung horizontally, but in both photo sessions, the painting is standing upright. Even more interesting is that in the ‘Kamares’ photo, the painting is tilted 90 degrees to the right, whereas in the ‘Parnakh’ photos, there is an identical tilt to the left.

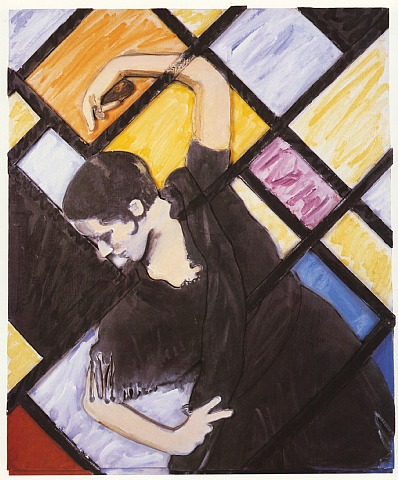

1992: The American pop artist Larry Rivers created an original work based on the ‘Kamares’ photo. Rivers remained relatively faithful to the division of shapes and the original colouring, though none of the hues expresses the vibrant intensity of the original work. And there is another striking link: in van Doesburg’s photo, the dancer is actually posed in front of the painting, while Rivers, to the contrary, has chosen to blend the dancer and the accompanying painting onto the same plane. The black stripes that cross the dancer’s body are marginally discernible and not immediately noticed because Rivers left the dancer’s neckline bare. He had, however, hinted at a black stripe on the dancer’s uplifted arm. Rivers’ dancer, as Parnakh before her, is inseparable from the painting.

Right: Larry Rivers – Van Doesburg’s Diagonal and Kamares; The Dancer 1 – 103.84 cm x 85.72 cm – 1992 – Artnet

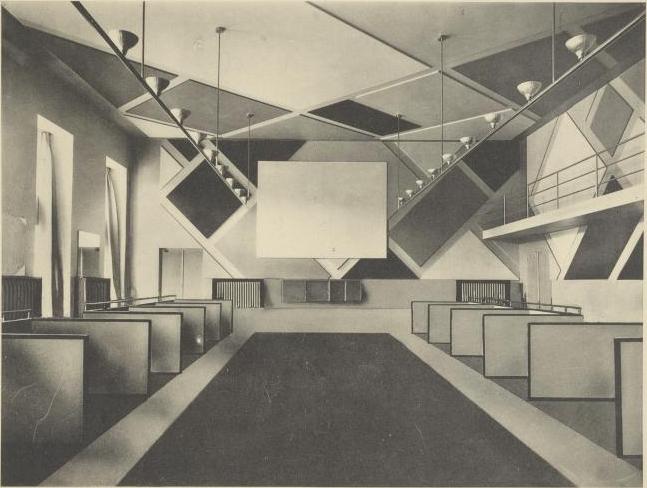

Back to 1926: Hans Arp and his wife Sophie Tauber-Arp invited Theo van Doesburg to join them in redesigning the interior of the Aubette, a once popular entertainment venue in Strasbourg. His designs for the Cinema-Dance Hall, also called Ciné-dancing — elementary forms, straight lines, the three primary colours together with black, grey, and white — are highly reminiscent of his counter-composition paintings. Van Doesburg, true to Elementarism, arranged a colourful diagonal grid pattern of squares, rectangles, and triangles. Aubette presented Van Doesburg with the opportunity to put his vision ‘to situate man within painting, rather than in front of it’ into practice.

Right: Van Doesburg’s designs were replaced in 1938 and fortunately restored starting in 1985. This photo shows the restored Ciné-dancing

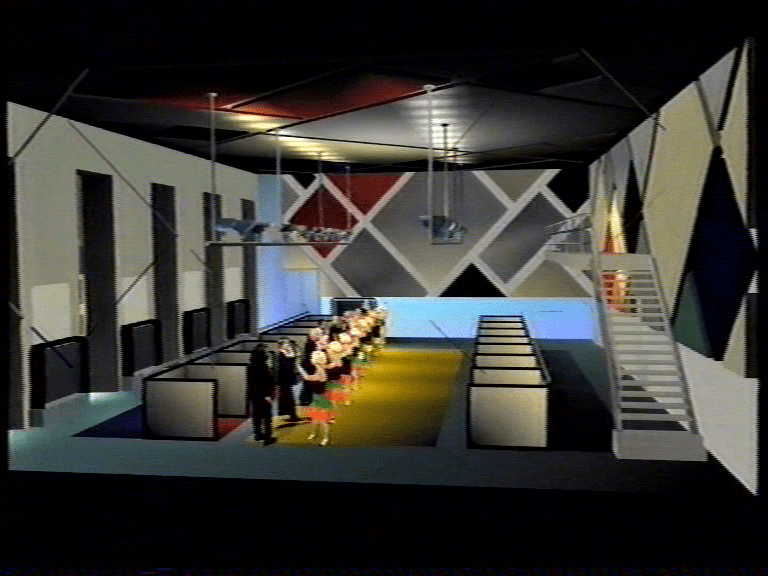

Man, apparently, did not wish to be situated within a painting. Just ten years after the innovative restoration, the interior of Aubette was redesigned to better provide to the tastes of the outgoing public. Years later, the revolutionary designs were restored, inspiring the Dutch dancer/performer Karin Post to produce a documentary/dance film inviting prominent architects, writers, designers, and artists to the restored Aubette to explore, comment on, and evaluate Doesburg’s design. Their pertinent remarks were interwoven with vintage films and a number of dance scenes, including duets and a group of mechanically dancing waitresses. The entire Ciné-dancing, including the balustrade, became the setting of this unusual film, which, through an artfully crafty montage unified the vintage with the present, performance with discussion, innovative design with the individual, into a total artwork.

Left: a duet performed by Karin Post and Dries van de Post

Right: a still of the prominent guests and dancing girls in the overpowering designs of the Aubette

To give an impression of the everlasting influence of De Stijl, I have chosen three artists whose dance and movement images, to a certain extent, are indebted to the groundbreaking movement.

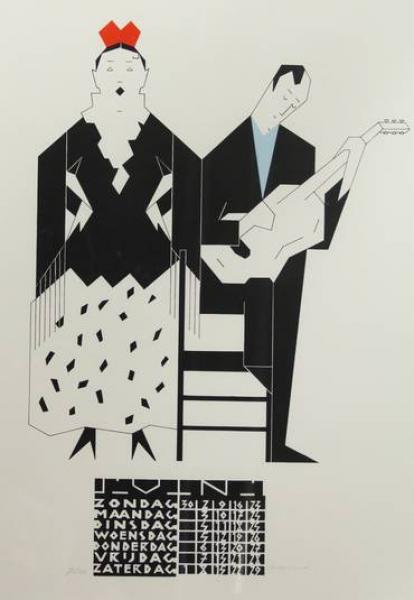

Bart van der Leck, an influential founding member of De Stijl, painted a few dance images in his pre-De Stijl period. Later, van der Leck turned his back on this expressionistic style to develop a streamlined realistic style where lines, shapes, and colour prevail. Hendrik Valk (1897-1866), inspired by van der Leck’s iconic style, created strong, realistic images exclusively using straight lines, geometric shapes, and definite planes of colour. The non-colour black is prominent, frequently staged against a light, non-descriptive background.

Left Spanish dancers – oil on panel, 57 x 53 cm – 1972 – Private Collection Henrik Valk/ presently Ligthart Art Dealers

Right: Flamenco Dancer with guitarist – lithograph,, 60 x 44 cm – exact date unknown – Auction House

I cannot conclude this post on De Stijl without introducing you to a lesser-known artist, Thijs Rinsema. True, the two paintings below are not dancers, but the kinetic energy of the depicted football players and jumping horses is second to none. Rinsema was never a member of De Stijl; rather, he enjoyed a close friendship with Theo van Doesburg.

Left: Football Players – opaque paint on paper – 1925 – 49cm x 60cm – Rijksdienst voor het Cultureel Erfgoed (incidentally, Rinsema painted approximately fifty paintings depicting footballs players)

Right: Jumping Horses – oil paint on triplex – 1926 – 30.5cm x 37.5 cm – Museum Belvédère, Heerenveen-Orangewoud, The Netherlands

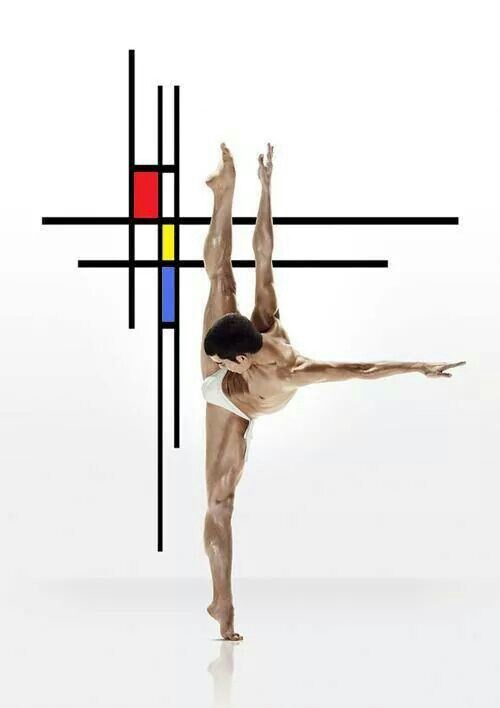

The final image, one of my favourites, is an astonishing photograph by the recently deceased Dutch photographer, Erwin Olaf. The sensuality and vulnerability of the human body are recurring themes in Olaf’s extraordinary work. He regularly worked with dancers, photographing members of the Dutch National Ballet, the Netherlands Dance Theatre and Introdans. He also collaborated closely with master choreographer Hans van Manen on a series of stunning black-and-white photographs.

This Mondrian-inspired photo is no less than spectacular. The extensions of the dancer, whose name I could not ascertain, are breathtaking. Just as impressive is that the dancer’s limbs, as far as humanly possible, are choreographed into horizontal and vertical lines. The line from the ground to his strongly pointed foot is perfectly straight. In fact, the dancer’s legs and arms mirror the Mondrian painting. Mondrian’s neo-plasticism concept materialises simultaneously in visual and performing art. Is there a more effective way to celebrate De Stijl?

(1) An illustration of La Danse was published in De nieuwe beweging in de schilderkunst, a critical text written by Theo van Doesburg. (1916)

(2)The quote by Van Doesburg that he ‘has poured out years of suppressed life’ is cited from a letter to his good friend J.J.Oud, 14th July 1916. The original Dutch is ‘omdat er jaren van opgekropt leven in uitgestort zijn’ – the translation is mine. Source Theo van Doesburg, oeuvre catalogus – page 160 – Centraal Museum, Utrecht – Kröller-Muller Museum, Otterloo 2000