Paris, 1930. When the oncoming American sculptor Alexander Calder (1898-1976) visited Mondrian’s studio at 26 Rue du Départ, he entered ‘a very exciting room’. It was as if he had ‘walked into a painting’. Calder was instantly struck by the light and the whiteness of the space. On the solid wall between the windows, Mondrian had placed coloured rectangles made of cardboard. The youthful Calder, imagining an even greater dynamism, suggested to Mondrian that it ‘perhaps would be fun to make these rectangles oscillate’. Mondrian, assuming an exceptionally serious countenance, replied,’No, it is not necessary; my painting is already very fast’.

Very fast? Have Mondrian’s mature paintings not an air of tranquillity? The assorted coloured blocks of harmonious sizes arranged in asymmetrical compositions, the broader and slimmer black lines that separate the individual blocks, and the unmistakable balance of colour and form culminate in an outward calmness that invites the onlooker to ponder well beyond the elements presented on the painted canvas.

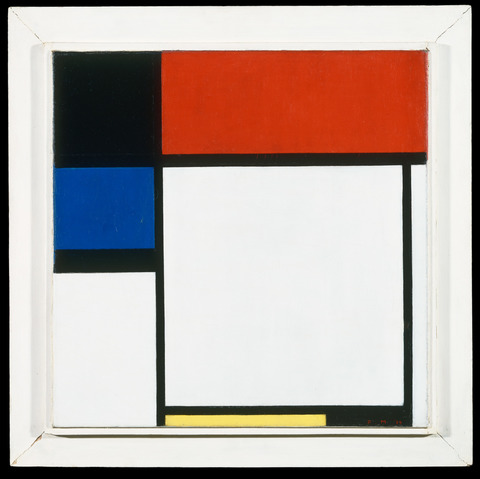

Fox Trot B, with Black, Red, Blue, and Yellow – 1929 – 45.4 x 45.4cm – oil on canvas – Yale University Art Gallery (Original title

Composition no. III)

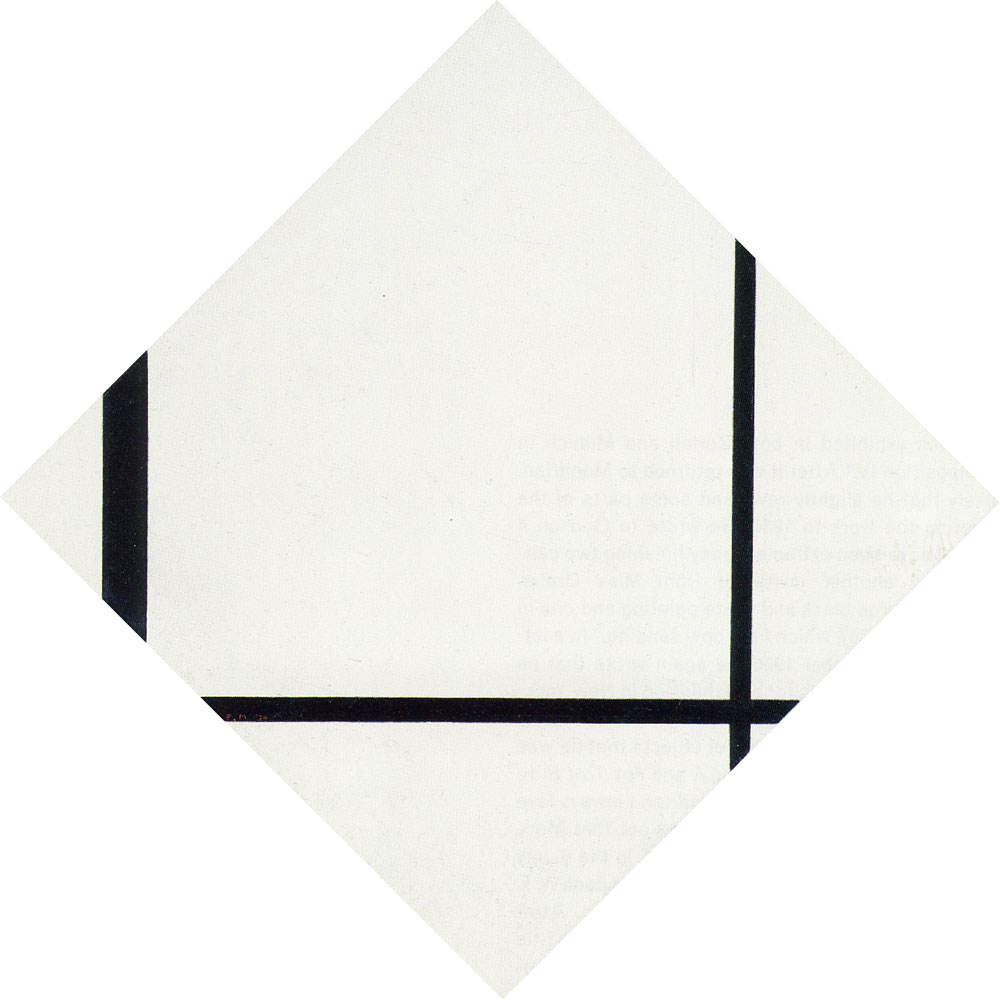

Fox Trot A: Lozenge with Three Lines – 110 cm diagonal, sides 78.2 x 78.2 cm – Oil on canvas – 1930 – Yale University Art Gallery,

(original title – Composition no. IV)

Fox Trot B and Fox Trot A, as discussed in the previous post, are typical of the artist’s work in the 1920s and early 1930s. At first glance, they may evoke an impression of motionlessness, yet beyond their transcendental calmness lingers a restless dynamism. Mondrian was a master of duality. He juxtaposes the horizontal with the vertical, the regular with the irregular, colour with non-colour, the symmetrical with the asymmetrical, culminating in an energetic momentum of opposing rhythms.

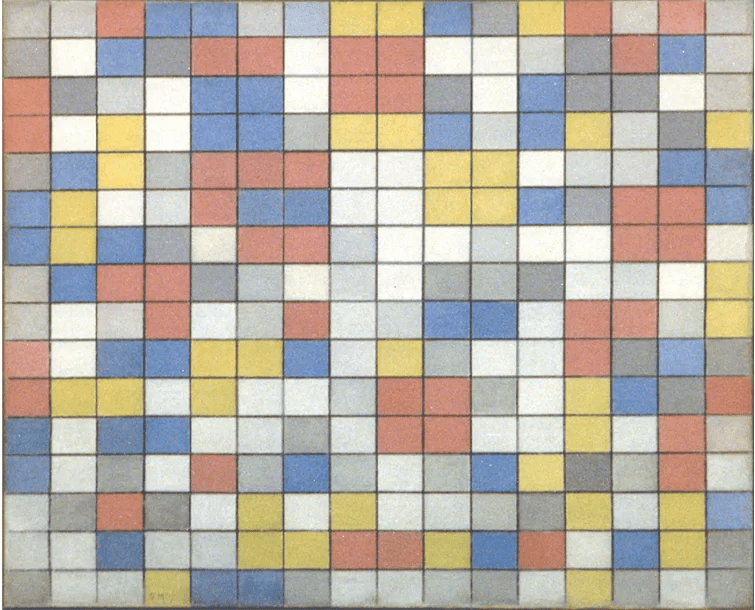

An earlier work, Checkerboard Composition with Bright Colours, is not explicitly related to the Foxtrot or any other dance, but unquestionably features all the opposing elements mentioned above. This innovative painting presents a rectangular grid of vertical and horizontal lines. The canvas is subdivided; each row, whether vertical or horizontal, consists of sixteen identical, small rectangles. The painting conveys the impression of balance and harmony. Yet within this apparent harmony, Mondrian juxtaposes colours and non-colours in an ostensibly random fashion. At times, one colour may form a block of four identical shapes. Just as common are groups of three or more blocks designed in an L-shape placed upright, edgeways, or inverted. And throughout the entire grid, groups of single and double blocks are scattered in an unpredictable pattern. The restlessness of the coloured shapes contrasts with the linear stability of the grid; the rhythmical momentum is embraced within a stable, harmonious whole. Mondrian investigates oppositions, juxtaposing space, colour, movement, and rhythm; the painting is none other than an exploration of rhythmical propulsion.

Rhythm fascinated Mondrian. He loved ragtime, was a great jazz enthusiast, collected jazz records, and, according to insiders, played his favourite numbers as he painted. It boggles the mind to imagine Mondrian listening to vivacious jazz rhythms while painting his harmoniously austere works. For Mondrian, rhythm was so much more than music and visual art. Mondrian was a dancer; he had rhythm, dancing the latest social dances at every opportunity. His New York dancing partner, the artist Lee Knasner, points out that, though Mondrian had taken dancing lessons, he preferred to improvise. ‘No matter the music,’ she continues,’Mondrian danced in a ‘staccato’ manner with his head thrown back. It seems to me his movement was all vertical, up and down. The complexity of Mondrian’s rhythm was not simple in any sense’.

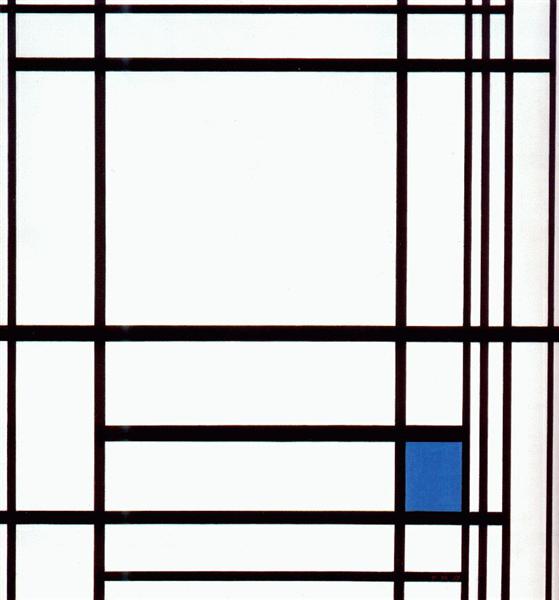

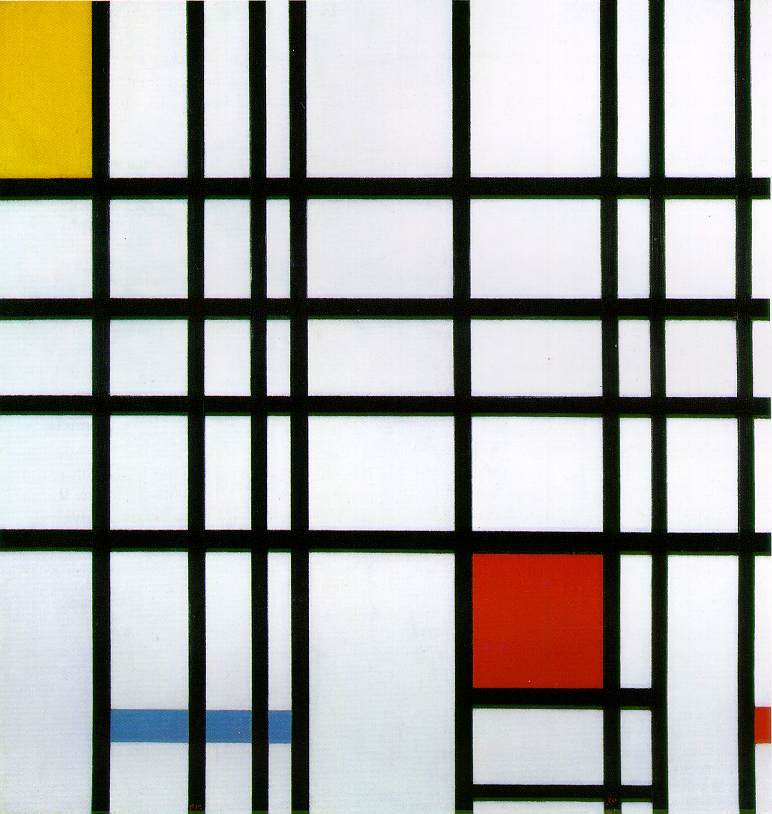

Composition with Red, Yellow, and Blue - oil on canvas – 1937 – 1942 - 72.5 cm x 69 cm- Tate Modern, London

Mondrian’s entire oeuvre is devoted to visualizing rhythm. From his early work to the final stages of his Neo-plasticism, recurring shapes, colours, and structures play a foremost role. The above two paintings, exemplary of Mondrian’s work in the 1930s, illustrate the painterly element of rhythm merged with musical and dance rhythms. The repetitive lines, differing in width and spatial structure, the distinct asymmetrical white shapes and occasional coloured component, can be read as a musical score or, just as probable, a dance floor pattern. Even the ‘flat canvas’ is more than meets the eye. A prolonged look reveals that both the horizontal and vertical lines interweave incessantly, leaving an impression of depth and continual oscillation. Clearly, Mondrian’s duality is at work — a cool, abstracted composure that radiates continual kinetic momentum.

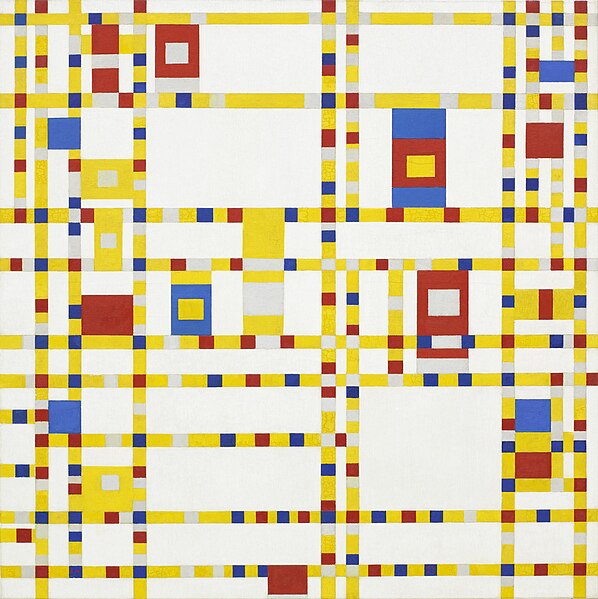

In the face of an impending war, the sixty-eight-year-old Mondrian left Europe to arrive in New York in late 1940. He immediately embraced New York, captivated by the bright lights, the hustle and bustle of city life, the jazz cafés, and the latest music trends. Mondrian, according to information presented on the MoMa internet site, was introduced to Boogie-Woogie on his very first evening in New York. The now-venerable artist apparently danced to the compelling rhythm with youthful gusto. He soon translated the vitality of New York City onto the canvas, integrating the rhythm and exuberance of the boogie-woogie in his artworks; the austere black lines made way for lines of colour and blocks of solid colour together with small pulsating squares appeared on what was previously an ascetic grid. Broadway Boogie-Woogie (1942-43) and his last work, Victory Boogie-Woogie, reflect the rhythm of the city, the rhythm of jazz, and the rapid, dynamic rhythm of the popular dance trend.

Is Broadway Boogie-Woogie an allusion to the bustling city of New York? Do the dazzling small blocks echo people scurrying down the sidewalk, or do they suggest the flickering of stop lights? The larger forms, it has been suggested, may evoke the myriad of yellow taxis rushing through Manhattan streets. This line of thought would explain the Broadway component of the title, but not the music/dance term Boogie-Woogie. Jazz pianist/composer Jason Moran* offers a convincing explanation. The musical structure of boogie-woogie is composed of boogie, a consistent rhythmical cadence, played by the left hand, and the solo/improvisation section, woogie, played by the right hand. It is, Moran explains, as if two worlds converge on the keyboard. Boogie, in the painting, is represented by a consistent pattern of small squares, while the larger yellow, red, and blue blocks, arbitrarily placed, render the solo element. Moran recognizes Broadway Boogie-Woogie as a vibrantly dynamic musical score. Mondrian’s blocks, lines of multicoloured squares, and regular and irregular spatial design all culminate in a visual pulse that is equally potent to art, music, and dance.

Dance-wise, the Boogie-Woogie, family of rock’n’roll, is energetic and high-spirited; dancers bounce and rock effervescently, duplicating the constant beat of the pianist. Meanwhile, the upper body improvises an array of vivacious moves. The upper and lower body, though in opposition, are in continual conversation with each other.

New York, early 1940s. Could Mondrian have foreseen that when he, slightly offended, corrected Calder saying ‘my painting is already very fast‘, that a decade later his last paintings would become even faster? If Broadway Boogie Woogie is fast moving, Mondrian’s last painting, posthumously* * named Victory Boogie Woogie is ‘very fast‘. In a pandemonium of primary colours, Mondrian has assembled strips of squares and rectangles that intermingle with an abundance of multi-sized blocks. The myriad of colours and forms, choreographed in a rhythmical composition, appear to dance vigorously over the canvas. This effervescent effect is further heightened by the disappearance of the iconic black lines; only a sprinkling of black square patches remains. The large diamond-shaped canvas is a work in progress; layers of different coloured tape and squares of coloured paper still lay dormant in the unfinished work. Victory Boogie Woogie, painted between 1942 and 1944, presents a fascinating insight into the artist’s intense exploration of colour, form, space, proportions, rhythm, and oppositions.

I will leave the concluding words to Piet Mondrian himself;

Many appreciate in my former work just want I do not want to express, but which was produced by my incapacity to express what I wanted to express – dynamic movement in equilibrium. But a continuous struggle for this statement brought me nearer. This is what I am attempting in ‘Victory Boogie Woogie’

Piet Mondrian

*In a very interesting podcast ,’The way I see it’, Jason Moran ‘shares his view of Piet Mondrian’s Broadway Boogie Woogie and feels moved to music by its straight lines and blocks of colour. ‘ (BBC Radio 3) I have provided a direct link in the text under pianist/composer Jason Moran.

** Mondrian had spoken about the unfinished painting in terms of victory and boogie woogie. The name Victory Boogie Woogie, though posthumously titled, was inspired by the artist himself.