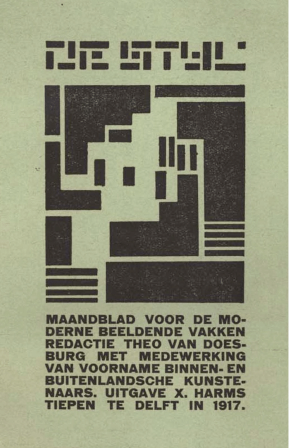

The name Vilmos Huszár may not immediately ring a bell, but the Hungarian-born, naturalized Dutch artist Vilmos Huszár (1884-1960) was a founding member of the revolutionary art community De Stijl. The group, founded in 1917, initially united four artists — Theo van Doesburg, Piet Mondrian, Bart van der Leck, and Vilmos Huszár — each exploring innovative artistic paths. The members of De Stijl envisaged a universal language that was neither representational, narrative, nor illustrative. The artists conceived art in terms of line and colour; their vertical and horizontal lines and shapes painted in primary colours are iconic. To promote their ideas, the group published a magazine titled, like the group itself, De Stijl. Theo van Doesburg, the driving force behind De Stijl, was the editor in chief.

Vilmos Huszár’s cover design for the inaugural issue of the magazine immediately proclaims De Stijl’s avant-garde convictions. Huzsár, like the other members of De Stijl, pursued the essential. Shapes are tapered to the most rudimentary form to be rendered in geometrical terms, exploring the gamut of the vertical and horizontal lines. Huszár’s cover addresses the question of two-dimensional design; he eliminates the difference between the foreground and background; black and white have the same value.

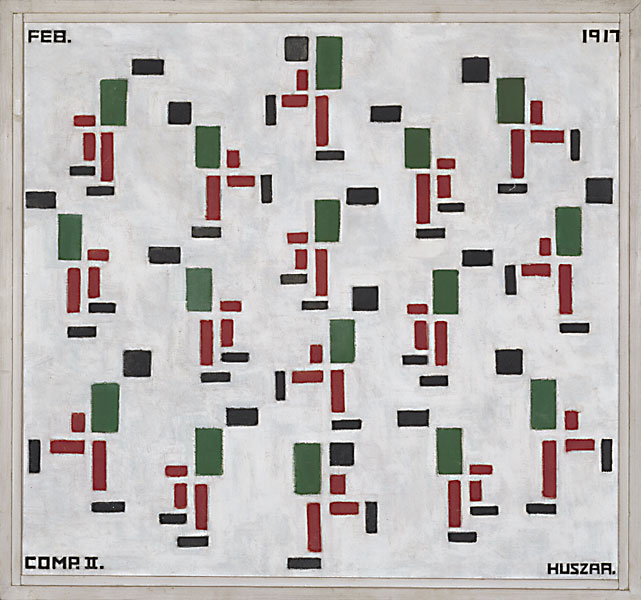

Composition II (The Skaters), discussed in the previous post, calls our attention to Huszár’s fascination with movement. All the green, red, and black figures, even though stylized into blocks, appear to skate. Huszár explored the options of composing a structured painting, preserving harmony and order, and at the same time suggesting locomotion.

Vilmos Huszár Left: Design for the cover of the inaugural issue of the magazine De Stijl – Volume 1, no. 1 – October 1917 Right: Composition II (Skaters), 1917 – 74 x 81 cm – oil on fibre cement – Kunstmuseum, The Hague

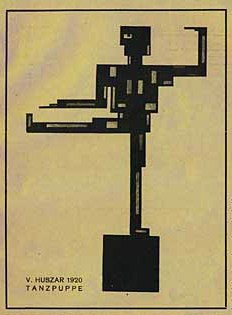

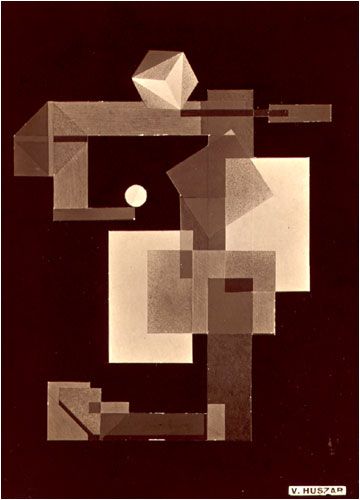

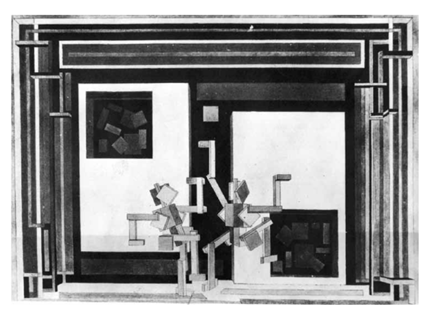

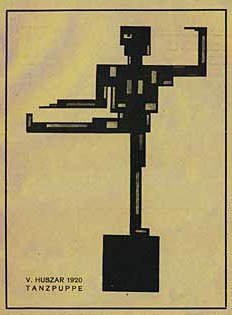

The perception of movement was vital to Huszár’s work. Early in his career, Huszár devised a design for a puppet-like figure, the Mechano Dancer. The monochrome construction combines horizontal, vertical, and diagonal shapes assembled one upon the other. The structure, suggestive of a human figure, has a cube at the top and varying rectangles, possibly suggesting torso, arms and legs. This hybrid man-machine may have been intended for the theatrical performance, which Huszar extensively describes in an article published in De Stijl (August 1921). The artist explains his concept, unfolds each of the four episodes and gives directions for the choreography and the mis-en-scene. In the opening scene, the blocks are moved around the stage in an interaction of colour, shapes, and proportions. In the following scenes, one or two figures move in an ever-changing composition of colour and shape. This theatrical concept was never performed, but it does give an insight into Huszár’s scope of creativity and his interest in theater. He was no doubt inspired by other artists, including Picasso, who designed astonishing costumes for the managers in Parade (1917), the theatrical experiments by Kandinsky, the Bauhaus and not to forget, the theatrical innovations by Fortunato Depero, a leading Futurist.

Vilmos Huszár Mechano-Dancer 1922 – private collection Composition 1920-1921 (Gestaltende Schauspiel) De Stijl, August 1921, page 127

During the same period that Huszár designed the Mechano Dancer, he also devised a mechanical dancing figure that was actually used in public performances. The Mechanical Dancing Figure considered an early form of kinetic art, was a black aluminium puppet just under a metre in length. The figure was constructed from rectangular shapes, all containing a number of indentations. These openings in the legs, arms, torso, and head were covered with red and green mica. The puppet, curiously, had one red and one green eye. It was operated by a series of snares attached to ten keys situated behind the platform. Each movement of the snare initiated a specific function. The Mechanical Dancing Figure could turn his head, lift his legs and arms, and also bend his elbows and knees. The puppet was manipulated from behind a white screen, reminiscent of the Wayang, the Indonesian shadow play. The effect: a silhouette of a rectangular dancing figure, moving solely at right angles with rectilinear areas of glowing red and green colouring.

Vilmos Huszár – Mechanical Dancing Figure (1917-1920) Left: Mechanische Dansfiguur leaf from the magazine Merz 1, januari 1923 p. 13 Centre and Right: reconstruction of the Mechanical Dancing Figure, front and back view – Kunstmuseum, The Hague

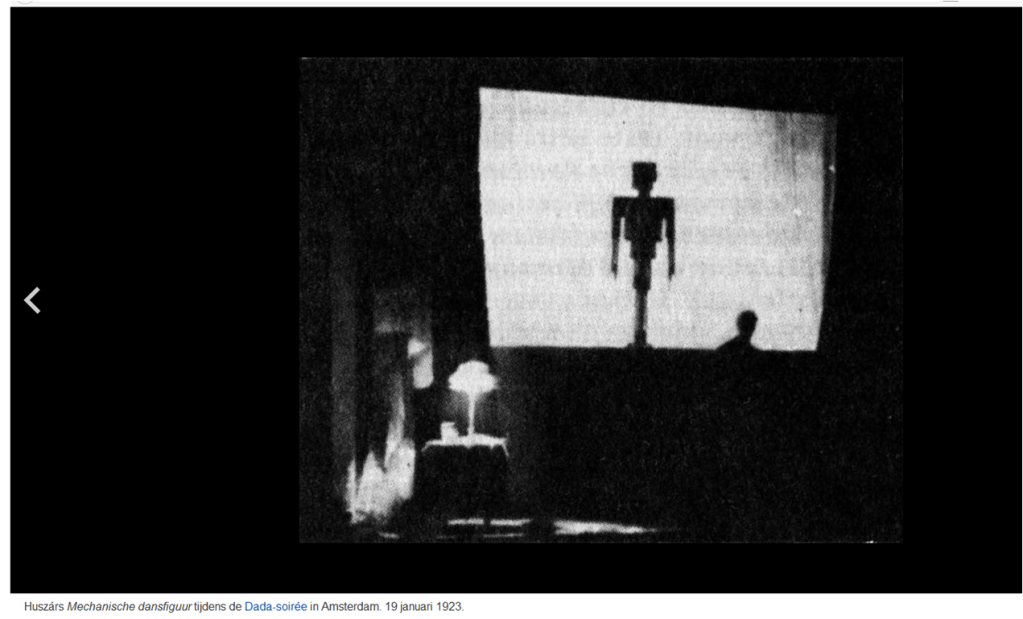

After a series of private try-outs, Huszár and his Mechanical Dancing Figure joined forces with Theo van Doesburg, his wife, Nelly van Doesburg, and Kurt Schwitters in a season of Dada evenings, the first being held at the Bellevue Theatre, Amsterdam, January 1923. The constant element, in the ever-changing Dada program, was the dance of the mechanical puppet. The dancing figure was accompanied at the piano by Nelly van Doesburg. She may elect to play Vittorio Rieti’s The Wedding March for a Crocodile or some other bizarrely titled composition, like Military March for an Ant. Meanwhile, Kurt Schwitters uttered peculiar noises or recited one of his clamorous poems. Pandemonium ensued.

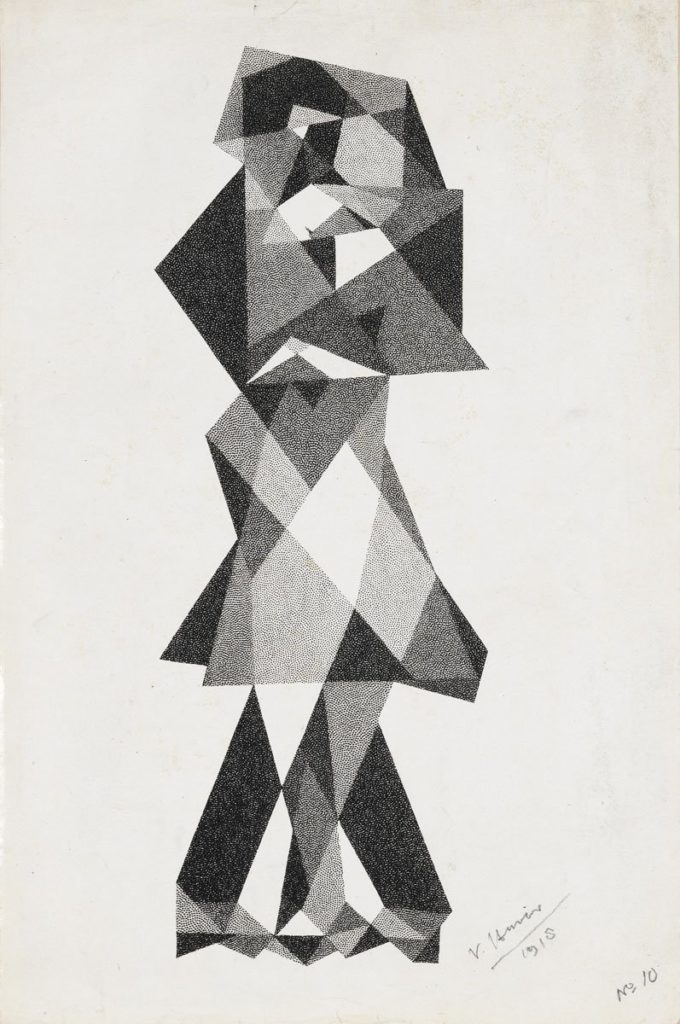

In his earlier years, Huszár lived in The Hague, actively participating in the city’s social and cultural scene. A number of paintings depicting dancing couples derive from this period. Composition (Two Figures), a black and white lithograph dated by the Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest as created in 1928, is also dated, presumably by the artist himself, as 1918. Whether created in 1918 or 1928, the work clearly reveals Huszar’s sense of movement and dynamics. I discern a couple embracing each other intimately, performing a continual whirling activity. The direct interaction of their legs and the swirling skirt supports this assumption. The figures are inseparable, not distinguishable, and totally intertwined. The work is constructed from triangles, rectangles, diamonds, and other sharp-edged geometrical shapes that partially overlap each other. All the shapes consist of three or four corners linked by diagonal lines. Square shapes are altogether excluded. I get the impression that pieces of shattered glass have been assembled into a representational, though not realistic, form. An interesting detail is that Huszár designed a number of stained-glass windows.

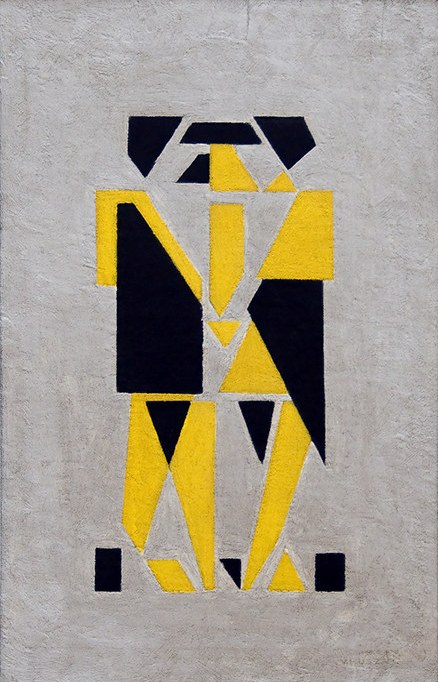

I find Composition (Two Figures) perplexing. On the one hand, Huszár, an artist loyally affiliated to De Stijl, has devised a harmonious two-dimensional work consisting of geometrical shapes with acute and obtuse angles, flat planes, and stark forms, all stylistic traits of De Stijl. Yet, this very same thoughtfully constructed figure gives the impression of perpetual circular locomotion. The figure turns on its axis; a three-dimensional action within De Stijl’s rigid two-dimensional concept. Huszár uniquely superimposes circularity upon a flat angular figure. Couple Dancing, painted around 1928, presents no such dilemmas. The couple is not intertwined; rather, they confront each other in an apparently stationary pose. It is only the indistinct position of the feet that possibly provides some indication of their dancing activity. Not dissimilar to the construction of Composition II, yellow and black geometrical shapes of varying sizes and forms are assembled to construct a schematic representation of an existing object, in this case, a dancing couple.

Vilmos Huzsár Composition (Two Figures) – 292 mm x 194 mm print, lithograph on paper (1918) 1928 – Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest * Couple Dancing – 46.5 x 30.5 cm – oil on panel – c. 1928 – Kunstmuseum, The Hague

The final dance image, also titled Couple Dancing, was long thought to have been painted in 1917. At the Kunstmuseum, The Hague, where the painting is displayed, researchers concluded that the work was created somewhat later, in 1938/9. Interesting is that Huszár, even after he left the group in 1924, revisited his groundbreaking convictions.

Using primary colours and the non-colours white, black, and grey, Huszár constructs a segmented figure of a man and a woman. I have the impression that they are actually moving towards each other. The white triangular shapes, with the vertex extending to the outer edges of the painting, add to the sensation of forward locomotion. Equally convincing is the positioning of the ‘head’. The opposing yellow triangles, complemented by multiple cornered blue shapes,’look’ directly, even avidly, at their partner. There is an obvious distinction between the two figures, both in the physique and attire. The man is taller and is constructed in a variety of black forms. It is easy to imagine him wearing a tuxedo. The woman, relatively shorter, is represented by a combination of three varied grey shapes. Positively eye-catching is that small red square in the centre, nestled in a white inverted triangle that traverses both figures. And to connect the figures, Huszár had added a striking, narrow, elongated, red rectangle at the very base of the painting. Depending on the viewer’s interpretation, this painting, not unlike Composition II (Skaters), can be seen as a two-dimensional work, abandoning the differentiation between the foreground and background. But just as easily, the viewer can discern a neutral background with dancing or skating figures in the foreground.

Couple Dancing oil on canvas – 100cm x 60 cm – 1938-39 Kunstmuseum, The Hague

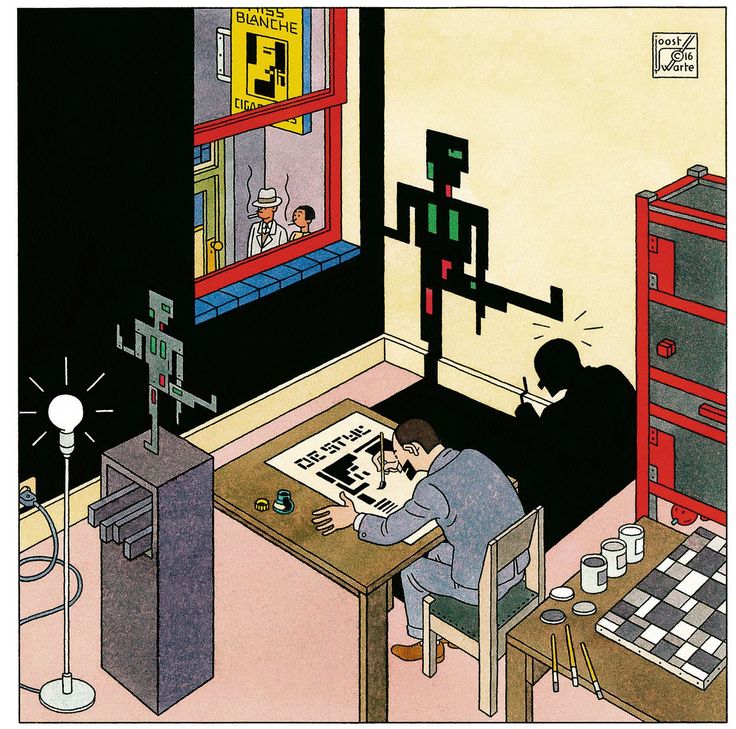

As part of the centennial celebrations of De Stijl, Joost Swarte, known for his magnificent strip book illustrations, illustrated ‘En Toen de Stijl’ an informative strip book with drawings depicting the ideas, themes, and oeuvre of De Stijl’s renowned artists. Huszár, besides being a painter, was a designer of furniture, stained glass windows, and of applied art. His best-known graphic design is the Miss Blanche cigarette campaign. The following colourful illustration shows a diligent Huszár composing the title page for the first edition of the magazine De Stijl. On the table behind him lay Composition in Grey (1918), a painting abandoning perspective composed exclusively of squares, rectangles, and straight lines. The cupboard at the side is just one example of his furniture design, and through the window, a Miss Blanche signboard hangs prominently above two smoking pedestrians. And finally, the Mechanical Dancing Figure is pictured twice: the small puppet and its large, towering shadow, which, from my point of view, has a somewhat cheeky expression. Huszár was definitely a versatile artist.

Published by Leopold – ISBN: 97890258723810

*There is another version of this work, titled Danspaar (Couple dansant). There is an illustration in Danser sa vie, an exhibition catalogue published by the Centre Pompidou, Paris. This version uses colour; the dancers are shown in black, grey and blueish-grey hues. With the exception of this colouring this version is identical to the lithograph housed in the Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest. The accompanying text offers no further information. The work, created in 1928/29, is in a private collection.

Danser sa vie – Art et danse de 1900 à nos jours – Centre Pompidou – ISBN 978-2-84426-525-8, Paris 2011

Further reading

- De Mechanisch dansende figuur van Vilmos Huszár – Sjarel Ex and Els Hoek – ISBN 90 6322 107 – Reflex – Utrecht 1984( Dutch)

- Holland Dada, K. Schippers – ISBN 90 214 1369 8 – Querido Uitgeverij 1974 (Dutch)