In my last post, I suggested that the iconic paintings of dancing peasants by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, his sons, peers, and followers, are so well-known that modern day audiences might overlook the abundance of polite dance images created in The Low Countries during the 16th and early 17th century. The previous post, therefore, delved into court dancing performed by courtiers in Renaissance palaces and great halls. This post will look at an alternative approach to fashionable dance; images of dancing in brothels and other places of ill-repute, starting with the tavern scene from the Parable of the Prodigal Son.

The Parable of the Prodigal Son, arguably due to the distinct moral implications, was a popular theme in Dutch and Flemish art. The great Dutch artist, Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669), created two masterpieces based on this theme, The Return of the Prodigal Son and a captivating double portrait, The Prodigal Son in the Brothel. In the latter painting, Rembrandt depicts a shamelessly tipsy man entertained by a beguiling woman. The prodigal son, heedless of the fortune he is squandering, enjoys the alluring company, the drinking, and the feasting.

Rembrandt focuses, marvelously I may add, on the characterization and expressiveness of personalities. Dance may play no role in this work, but dance definitely assumes the leading role in a work attributed to Frans Francken the Younger, where the centre painting, illustrating a thriving brothel scene, is enclosed within a grisaille frame depicting a number of episodes from the parable.

The artist instantly draws the viewer’s attention to the dancing courtesan and the prodigal son; note how intimately the lady of pleasure leans towards her eagerly reciprocating partner. The formation, posture, and body language of the couple is remarkably similar to the dancing couples painted by Hieronymus Francken the Younger. As in various other dance images by Frans Francken the Younger, the man is seen leaning faintly backward with his pelvis somewhat forward and one leg raised slightly upwards. I hazard to guess that this couple is dancing a slow, stately dance; quite possibly Frans Francken has chosen the fashionable 16th century pavane.

The following painting by Hieronymus Francken 1 leaves no doubt that the viewer has encountered a house of pleasure. Clues are plentiful: a platter of oysters, an erotic painting on the back wall, couples drinking, a hanging pub sign of a swan, someone peeping through the curtained window, and an aged procuress. The horrific scene, hazily illustrated between the wide-open curtains, of a man being ambushed by a swine clarifies that this apparently congenial scene is in fact a depiction of the Parable of the Prodigal Son.

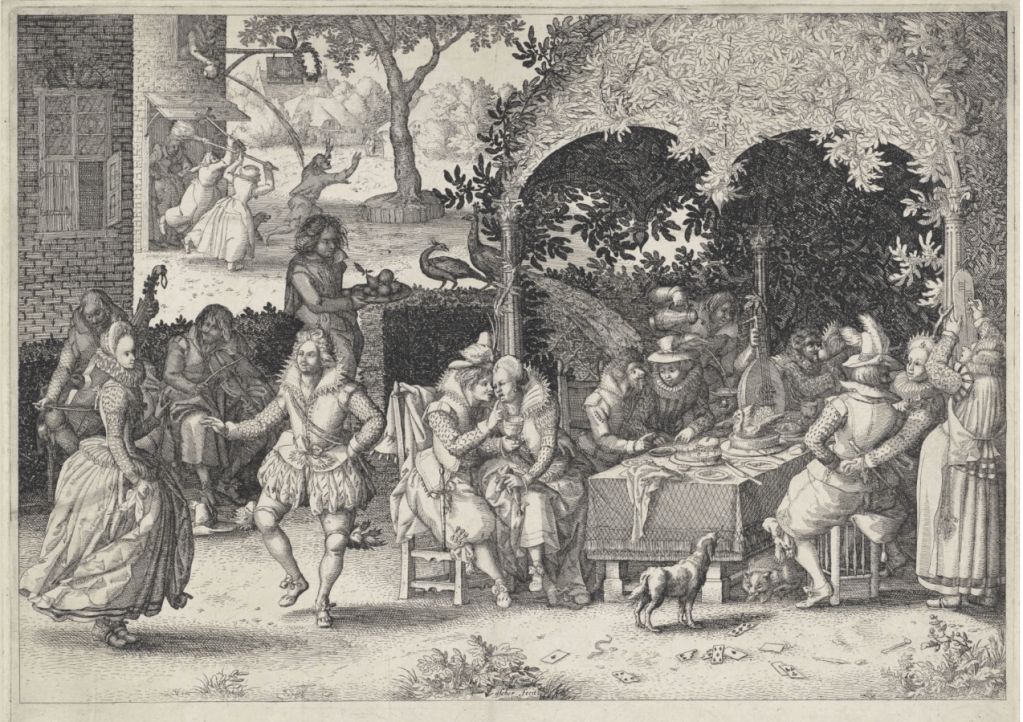

The courtesan playing the clavichord is imposing, enticing the spectator to enter the titillating chamber. Her long, well poised, statuesque posture strongly contrasts with the more inclined shapes of her embracing guests. It may be my imagination, but the prodigal son and his lady-friend appear to be lively dancers; their torsos swing from side to side, suggesting a swirling motion. Yet, animated or not, they retain the etiquette, style, and poise associated with the well-to-do. An engraving by Jacques (Jacob) de Gheyn II (1565-1629) after a design by Karel van Mander, is more candid. The scene depicts the squandering younger son in an outdoor setting, surrounded by ribaldry, bawdiness, some grotesque fools, an ensemble of instrumentalists, and a statue of Cupid pointing his amorous arrow.

This engraving is arresting in so many ways. Our initial attention is captured by the prodigal son; he is on the verge of dancing with a seemingly bashful harlot. Equally striking is the fool in the foreground mocking the goings-on and the bare-breasted, blasé woman nonchalantly holding a wine glass. But my favourite is the woman standing in front of the fountain. Her alluring glance entices the spectator; she virtually neglects the advances of her gentleman friend. Moving into the background, the artist reminds his viewer of the parable’s moral: the prodigal son is chased, banished, and left to wander forsaken by all.

The Parable of the Prodigal Son provided the ideal vehicle for the clergy, writers, and artists to explicitly discuss or illustrate moral issues. The above engraving, based on a design by David Vinckboons, presents the prodigal son dancing merrily, desirously perusing his dancing partner. Vinckboons/Jansz. Visscher chose to present the parable in a contemporary 17th century artistic genre, The Merry Company. All the party figures are extravagantly dressed, enjoy gambling, drinking, and lusting, besides being typically idle. As mentioned above, the swan, now pictured on the hanging pub sign and another decorating the flag pole, denote that this opulent setting is indeed a brothel. And of course, the male peacock, a symbol of excessive pride, is another indicator of a reckless lifestyle. If these allusions are insufficient to fathom the moral implications, the artist underlines the virtuous message with a background scene showing the prodigal son fleeing with all his might.

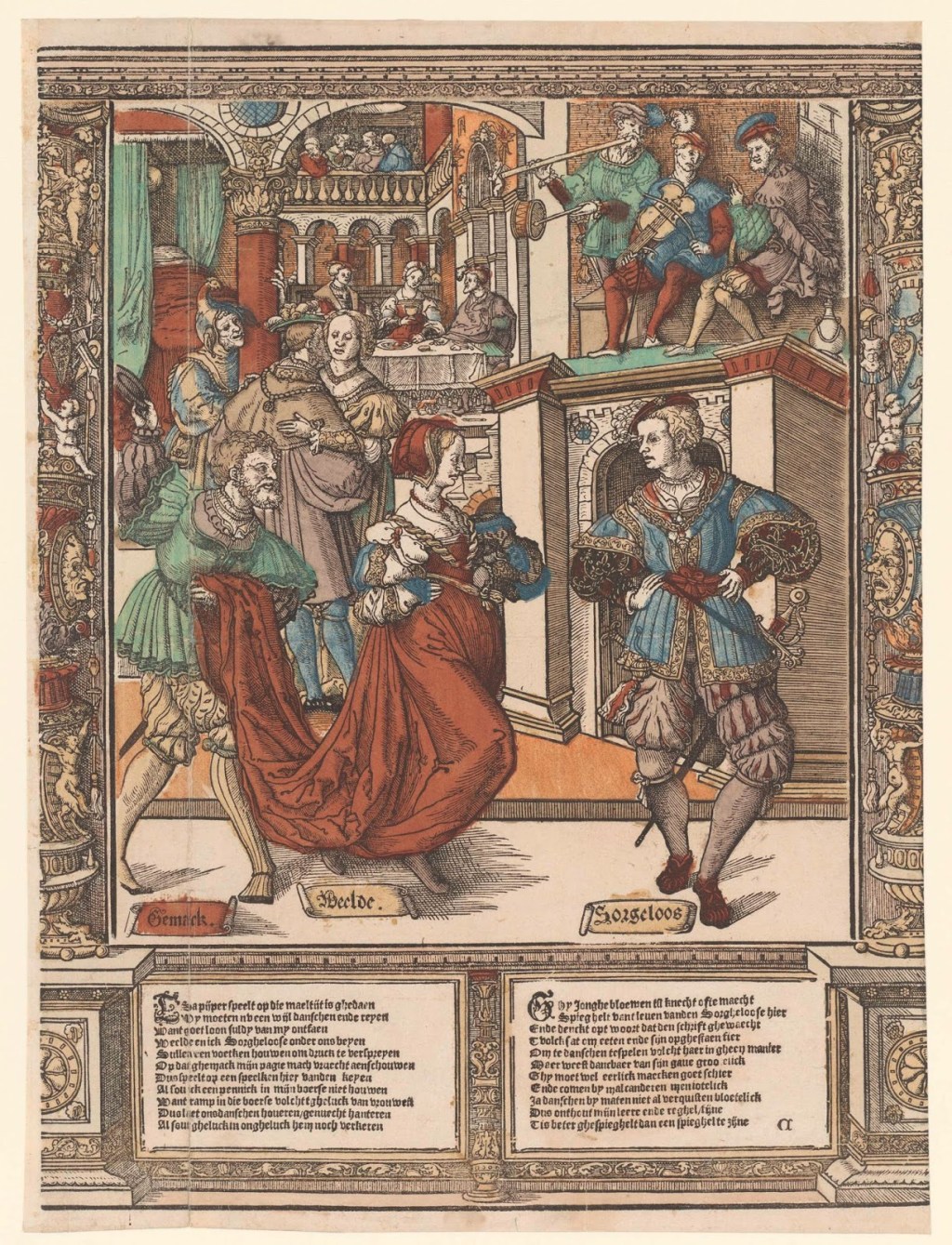

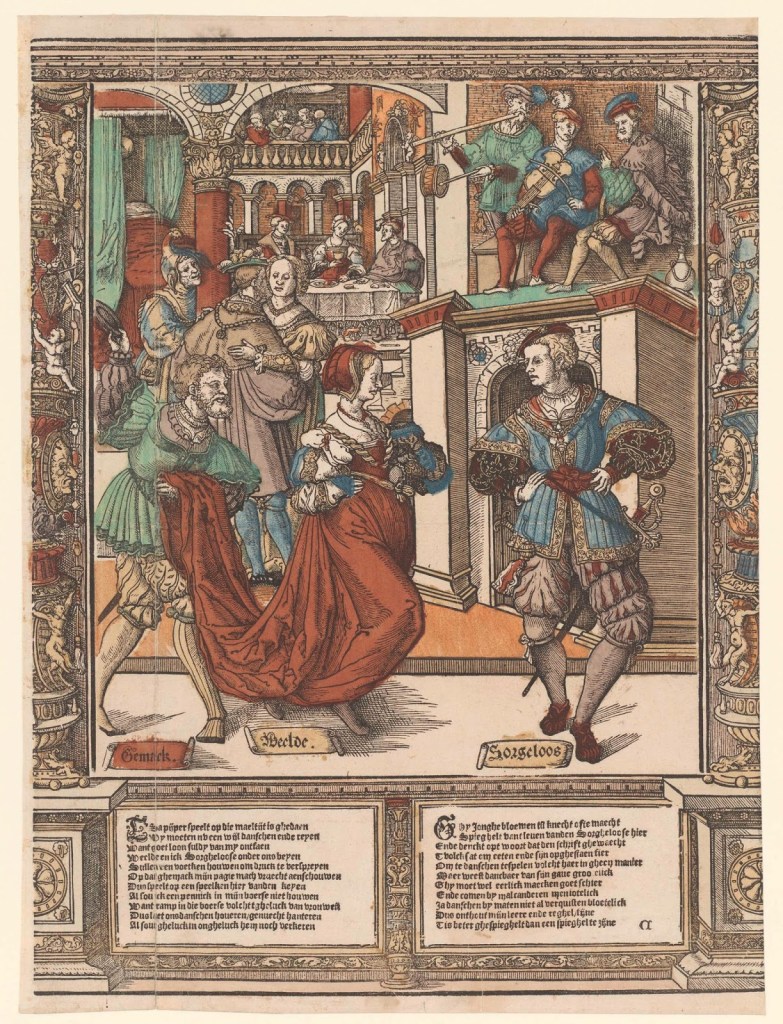

The Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam houses a set of six wood engravings by the painter, engraver, and map maker Cornelis Anthonisz (1505-1553) that presents a variant of the Parable of the Prodigal Son; The Story of Carelessness. After leaving home, Carelessness, accompanied by Wealth and her servant Comfort, arrive in a tavern, come brothel, indulging in all the delights ‘The House of Luxury’ has to offer. The third engraving,’The Ball’, depicts Carelessness, after inviting the piper to play a tune, inviting Wealth to dance. Standing side by side, this spirited couple dance a brisk dance. Comfort gently supports Wealth’s train, enabling her to jump, hop, and bounce from foot to foot. Behind them, another couple, embracing each other closely, dance more intimately, much to the fascination of the peculiar jester peering around the column.

This engraving, like the others in the series, is accompanied by two short texts composed by the writer Jacob Jacobszoon Jonck. The left side is reserved for a poetic description of the events occurring in the illustration. The text on the right, in contrast, imparts a warning damning the lifestyle enjoyed by Carelessness, who, like the prodigal son, unwittingly falls into the arms of Poverty, but unlike the prodigal son, has no father to welcome him home.

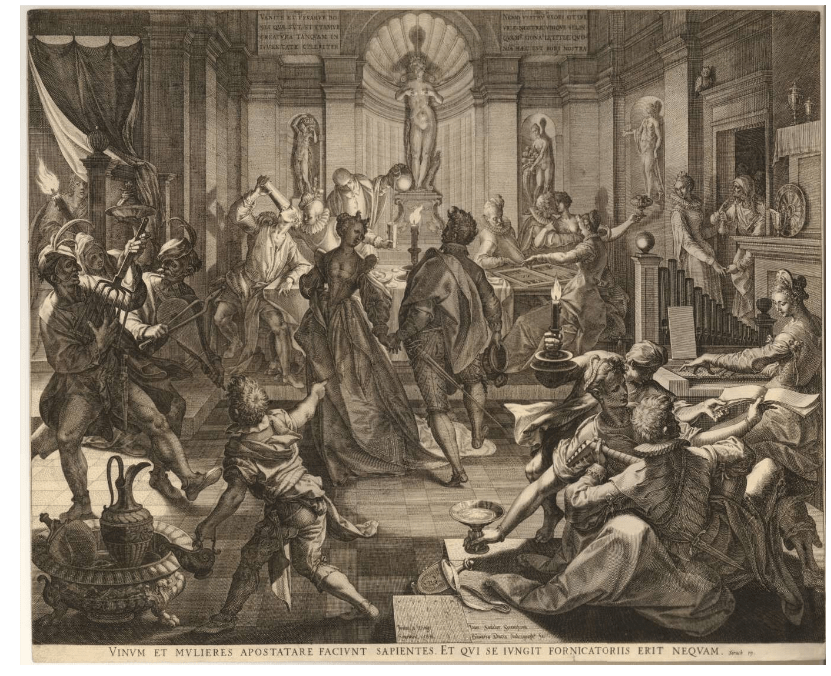

Last but not least is a marvelously popular 17th century print by Jan (Johannes) Sadeler (1550-c.1600), after an artwork by Joos van Winghe (1544-1603). Van Winghe created a number of versions, of which the original version, most likely, is a painting housed in the Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Brussels. Van Winghe’s work and Sadeler’s print, featuring an opulent interior of a brothel, are sometimes associated with and named The Prodigal Son, but more commonly titled Nocturnal party and masquerade.

The print presents an elegantly dressed couple dancing under the towering nude statue of Venus, the Roman goddess of love. The dancing couple are surrounded by a diverse crowd; comedians, musicians, a man drinking, people playing a type of backgammon (tric-trac), a man fondling a woman’s exposed breast and in the doorway a procuress encouraging a young woman. And seated on top of the lintel, partially obscured by the shadows, is the wise, observing owl.

Though not exactly in the limelight, the centre couple nevertheless, are eye-catching. They are evidently refined dancers. The woman, no doubt a courtesan, is exceedingly graceful. How to describe her? She is definitely stylish and most certainly flirtatious: all achieved with little more than a subtle shift of the hip accented by an elusive turn of her torso. Her partner not only complements her alignment but demonstrates his prowess with intricate footwork. That the candle-lit Venus forms a direct vertical line with the shaded dancers is not merely a question of composition or ornamentation. In the 17th century (and later, for that matter), dancing was considered immodest and equally objectionable as drinking, gambling and lechery. Nocturnal party and masquerade for all its gaiety, mischievousness, and drollery, serves as a reminder to all that transgressions, of which dance was one, lead to moral depravity.

Somewhere between 1580 and 1630, an anonymous artist revisited the popular print, transforming it into an oil painting. The same theme was retained, as was the foreground, the figures, the activities, but the interior design was fundamentally altered. The once spacious chamber with well-proportioned Roman statues adorning the niches is converted into a comfortable lounge with a traditional back wall; a traditional wall with three significant paintings; first Lot and his daughters, followed by Venus and Adonis and finally, the more optimistic theme depicting the Old Testament story of Tobias and the Fish.

In this relatively large painting, the gracious courtesan and her companion take to the dance floor. Possibly a second couple are joining in, although the man appears to be preoccupied with other matters. The anonymous artist, like Van Winghe and Sadeler before him, places the dancers at the centre of the composition, and then subsequently adds another reference to decadence: a gambling board is uncannily planted between the dancing couple.

The dance images introduced in this post are the work of Dutch and Flemish artists living in the same age as Pieter Bruegel the Elder, and his sons, Pieter Brueghel the Younger and Jan Brueghel the Elder. All the images highlight an accomplished dance style. All place dance in a dubious setting. All, in their own specific way, are didactic, conveying unmistakable moral implications.