Who is not familiar with Pieter Bruegel’s (1525 – 1569) iconic images of peasants dancing, drinking, and making merry? His son, Pieter Brueghel the Younger (1564 – 1638), together with many other Flemish and Dutch artists, emulated and developed the popular peasant theme. In fact, village scenes displaying hefty dancing peasants were so widespread that artworks illustrating Renaissance court and aristocratic dance tend to be overshadowed. Artists, needless to say, painted dance at court, nobles dancing in great halls, outdoor celebrations, and, at times, used elite dancing as a metaphor. Time to have a closer look at images of loftier, more dignified dance forms. This post will primarily focus on indoor court festivities; to set the mood I have included two exquisite images by the peerless Flemish miniaturists, Loyset Liédet and Simon Bening.

- Left: Loyset Liédet – Roman de Renaud Montauban – c. 1470 – BnF. Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal Ms-5073 f.117v

- Right: Simon Bening – Book of Hours ‘The Golf Book’ Add MS 24098, fol.19v – Bruges early 1540’s – British Library

Before discussing images of court dancing painted during Bruegel/Brueghel’s lifetime, it may be interesting to examine two prints, after Sebald Beham (1500 – 1550), engraved by the Netherlandish artist, Johann Theodor de Bry (1561 – 1623); these present a unique opportunity to compare how these artists and artists in general approached the representation of rustic and court dance.

The rustic dancers move in a multiple of ways, darting, twisting, and criss-crossing each other continually in what appears to be an improvised dance. The dancers bend, lunge, and propel themselves into crude poses, disregarding symmetry and constraint. Furthermore, they are earthbound, unbridled, undertake widespread actions on bent knees and freely display their lower legs. Moreover, men and women are equal partners; they share a similar spontaneity and have approximately the same height and posture.

The court dancers are regal, not to say, statuesque. They dance in a controlled manner, conscious of each gesture and every action. The man courteously presents his hand, leading his partner in a refined dance. Though the gentleman’s lower legs are visible, like those of the rustic dancer, his movements are sophisticated and preconceived, leaving neither room for playfulness nor improvisation. His graciously poised lady, subdued and rather demure, wears a voluminous skirt that hides her legs. Her footwork is of no visual importance. The heavy dress restricts her movements and most probably dictates a leisurely tempo. Where the rustic dancers are equal partners, in court dancing the gentleman takes the lead; his partner is designated to follow.

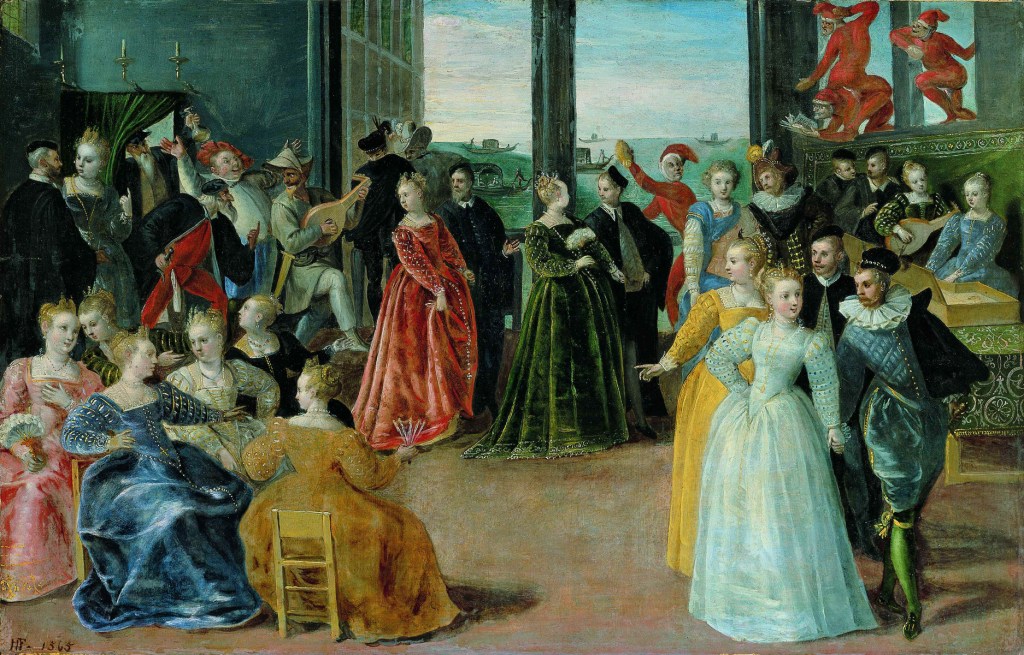

Grace, sophistication, and aplomb — all features of court dance — appear in the following painting, which embellishes practically every book on dance history. The elegant scene presents the ball accompanying Le Ballet Comique de la Reine (1581), a lavish court extravaganza acknowledged as the earliest ballet in theatrical history. The centre figures, the bridal couple, represent the Duke of Joyeuse and Marguerite of Lorraine. They are flanked by the King of France, Henri III, and his mother, Catherine de’Medici. The work has been attributed to the Flemish artist Hieronymus Francken the Elder (1540 – 1610), though the Dutch Renaissance artist Herman van der Mast (c. 1550-1610) has also been named. The Louvre, which houses the painting, attributes the work to the anonymous artist Maître des Bals à la cour des Valois. The identity of the artist who secured this commemorative moment for prosperity is, as yet, unresolved. Hieronymus Francken the Elder and Herman van der Mast are likely contenders; Hieronymus Francken trained in Antwerp before moving to France as a court artist at Fontainebleau, while Herman van der Mast was employed by the procurer general of the King of France. Both artists were established personages at court; undoubtedly, they frequented sumptuous aristocratic festivities.

Where the Wedding Ball is the epitome of elegant court etiquette, Carnival in Venice, a work accredited to Hieronymus Francken, is full of light-hearted elements juxtaposed against delicately poised, refined dancing couples. As the dancers progress in a composed, dignified choreography, various commedia dell’arte characters crash into the ballroom. An old, bearded man, Pantalone, astonishes both his musical companion and the demure Venetian ladies with his crude gesture. And to heighten the intrigue, masked carnival figures slither between the arches, teasing Venetian high society. The dancing couples, like all the aristocratic dancers in the previous images, are distinctly gracious, executing formal movements and skills, no doubt instructed by a dance master. In 16th century Italy, as in France, dance masters were members of the court staff employed to instruct the nobility in dance, deportment, and etiquette.

The Wedding Dance by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, exposing dancing, drinking, and flirting peasants, is, one may think, in no way analogous to Carnival in Venice. And yet, this convivial work was painted at approximately the same time as Bruegel’s iconic work (1566). It is obvious that drollery and mischief, so plentiful in Bruegel’s work, are also vital features in the Venetian scene. A close look reveals diverse and peculiar personages, indiscreet ribaldry, and a buoyant pleasure in liquor. Is that a courtesan conversing with the gentleman in black? Who are those two mysterious men wearing masks? And what tantalizing novelty are those ladies whispering about? Francken’s painting is filled with the unexpected; Bruegel and Francken are perhaps not as disparate as one might expect.

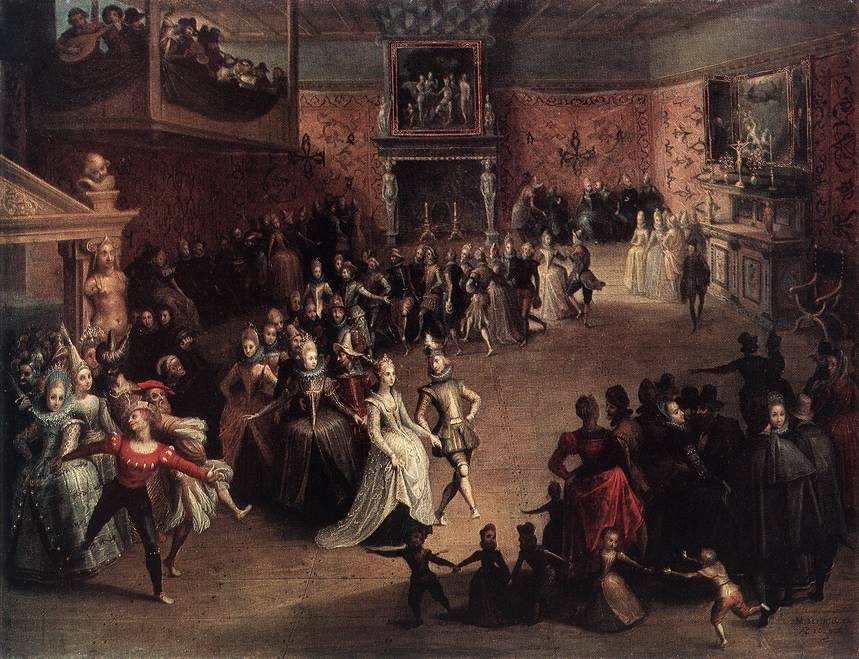

Very little is known about the life of Herman van der Mast, except that he studied with Frans Floris and that while in Antwerp he stayed with Frans Francken the Elder, the younger brother of Hieronymus Francken. Later, as already mentioned, van der Mast travelled to Paris; for seven years he was in the employ of Monseur de la Queste, knight and procurer-general to the King of France. This background information may shed some light on the possible identity of the artist of A Ball at the Court of Henri III. The Louvre attributes the work, once again, to the anonymous artist Maître des Bals à la cour des Valois, though the eminent British dance authority, Cecil Sharp, attributes the painting to Herman van der Mast. I can merely suggest Van der Mast was in the right place at the right time. (1 & 2)

A Ball at Court illustrates a palatial celebration presided over by Catherine de Medici and her son Henri III; opulent courtiers are dancing in a circular formation. A group of musicians, barely visible in the shadow, accompany the distinguished guests. The artist renders very little movement. In fact, the dancers appear to be stationary; for the most part, the artist seems more concerned with, or has been directed to, painting portraits of the notables attending the ball. Neither the movements nor the dress provide sufficient insight into the dance being performed. Luckily, the painting’s French title, Branle à la cour de Henri III, is helpful, indicating that the courtiers are dancing a branle. A feasible suggestion considering that the branle was a popular 16th century dance performed in an open or closed circle. Depending on the aptitude of the participants, a branle could be quick and lively or a somewhat gentler dance. After the reverence, all the dancers joined hands, stepping or galloping to the side before splitting into a couple formation to perform a jovial mime sequence. By means of a basic turn, partners either return to their original partner or move towards a new partner. This straightforward sequence was constantly repeated—the ideal social dance.

Not exactly aristocratic but nonetheless splendid are the wealthy, well-to-do figures in The Wedding Dance by Frans Francken the Elder. The bride and groom lead the wedding guests in a celebratory promenade. They are accompanied by a handsome man playing the lute. Frans Francken I gives little insight into the actual dancing movements; only the men’s well-portioned legs offer any indication of locomotion. We can, nevertheless, assume the dance steps are rudimentary; the hall is bursting with guests, essentially leaving little space for complicated choreography.

No doubt you will have noticed some baffling elements in The Wedding Dance; take those zany figures rushing past the curtains and the ominous painting hanging prominently on the back wall. The clown, Harlequin, is distressed. His companion, gazing through the curtain, is utterly overwrought. Some of these theatrical figures even carry torches, holding them frightfully close to the curtains. The musicians appear unaware of the commotion; the bride, on the contrary, is apprehensive. I wonder if the painting, a desolate tower standing in blazing surroundings, represents an unwelcome omen.

The genre, elegant balls, was developed by the brothers Frans Francken the Elder and Hieronymus Francken the Elder. Hieronymus Francken the Younger (1578 – 1623) and Frans Francken the Younger (1581 – 1642), sons of Frans Francken the Elder, continued to promote this genre. The following two works by Hieronymus Francken the Younger incontestably demonstrate his uncle’s inspiration: familiar are the couple leading the promenade, the lavish attire, the affluent setting, the musicians, and the commedia dell’arte figures. A new addition are the Oriental guests in Festive Company. In both paintings by Hieronymus the Younger, as in the work by Hieronymus Francken the Elder, the onlooker is compelled to look beyond the eye-catching frolicsome scene. Flemish paintings at the time habitually embodied various underlying moral concerns. In Festive Company, the background figures, though seemingly insignificant, are vitally indicative; take the group of vagabonds conversing with a woman of questionable morals, and, in the vista, figures performing dubious activities. The artist adopts another approach in Festive Company; he fills the front layer of the painting with a manifold of characters performing a variety of activities; the two wall paintings showing The Tower of Babel and Sodom and Gomorrah can easily be overlooked.

Hieronymus Francken the Younger – Festive Company – between 1607 and 1623 – oil on panel – 49.5 x 71 cm – Sold at Lempertz in 2011

Frans Francken the Younger painted a wealth of dance subjects, ranging from dancing mythological figures, to the Dance around the Golden Calf, the Danse Macabre, and, not surprisingly, court dance. He recurrently collaborated with Paul Vredeman de Vries (1567 – 1617) a master of painting the most elaborate palatial architecture. In the two paintings pictured below, the figures are by Frans Francken the Younger, and the majestic setting is by Paul Vredeman de Vries.

Ballroom scene at a court in Brussels presents Prince Philips Willem van Orange-Nassau, son of Willem the Silent, performing a stately dance with his spouse, Eleonora de Bourbin-Condé. An interesting tidbit is that an anonymous miniaturist painted the faces of the historical figures based on their official portraits. The court scene is stunning, just as is the skill and delicacy with which the company is costumed. In this glorious ballroom, only the prince appears to dance; his escort is ravishingly elegant in her motionlessness. Their dance can only be described as refined and of the upmost courtliness.

The sphere is somewhat different in A Ball in a Flemish Interior; the palace ballroom has been replaced by a grand hall. The vast space is filled with flirting, courting, gambling, and dancing couples. If I am not mistaken, there is a painting showing Susanna and the Elders just above the delicately carved wall decoration adorned with half-figure caryatids prudently crossing their arms over their bare breasts. In this ambiguous painting, the centre couple, in contrast to the stately court dance, is shown actually dancing down the room. Frans Francken’s II displays lively footwork, body shifts, hip undulations, and subtle revolving movements of the ladies’ skirt; he makes the sprightly couple come to life.

Members of the Francken dynasty feature predominantly in this post. The Francken family popularized the genre, court dancing, influencing others to follow suit. I cannot conclude without presenting a work by the Flemish artist Marten Pepijn/Pepyn (1575 – 1643) who worked with Frans Francken the Younger.

In this animated painting, we are invited to enjoy a bird’s eye view, so typical for early Flemish paintings, of a ballroom filled with dancing couples. These courtiers perform a lively dance. The leading couple is not at all bashful about raising their legs. The lady even raises her skirt to accomplish the vivacious dance steps. Moving down the long row, you can spot members of the court hopping, turning inward and outward, and raising their legs as high as noble propriety then permitted. In the left corner, a group of carnivalesque figures perform a somewhat less refined dance. Pepijn includes dancers, musicians, children, entertainers, and other guests, providing his audience with an all-embracing view of an extravagant royal festivity.

In the Age of Bruegel, paintings of peasant dancing were enormously popular, but paintings of the dancing privileged classes were no less sought after. The market for images of court dance, refined dance, or dance by the bourgeoisie never waned; the following post will look at yet another facet of refined dance.

1 – In his book The Dance, An Historical Survey of Dancing in Europe, Cecil Sharp attributes A Ball at the Court of Henri III to Herman van der Mast; caption under plate 27

The Dance, An Historical Survey of Dancing in Europe – Cecil J.Sharp & A.P. Poppe f.p. 1924

2 – The Louvre attributes both Wedding Ball of the Duke of Joyeuse and A Ball at Court of Henri III – Branle à la cour de Henri III to an anonymous artist named Maître des Bals à la cour des Valois.