For the 16th-century artist Rome was the place to be. Dutch and Flemish artists, painters, engravers, and sculptors flocked to the Eternal City intrigued by Roman antiquity, inspired by Italian masters, and inquisitive about many artists, particularly Raphael and Michelangelo. The journey south was hazardous; Pieter Bruegel the Elder, for example, ventured over the Alps even though wars raged in the region we currently call Germany. Other artists travelled by foot or wagon to Marseilles, continuing their adventurous journey by boat. Some even dared the most precarious of routes, sailing along the coast of Spain, despite the threat of Spanish rovers and Turkish pirates. Regardless of the impending perils, the Flemish artist Jan Gossaert (1478-1532) travelled to Rome as early as 1509 and Jan van Scorel (1495-1562), an artist from the Northern Netherlands, arrived in Italy in 1518. Neither of these influential artists painted dance images, but other, slightly later, 16th century pioneers approached dance in a variety of ways. Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s iconic dance images may not be indebted to Italian art, but the Flemish landscape artist, Paul Bril, does on occasion supplement his work with dancing mythological figures (1). And Bartholomeus Spranger, painter of mythological, allegorical and religious works, painted The Last Judgment in which dancing angels lead souls to heaven, reminscent in style to an earlier work by Fra Angelico. Other early northern artists, namely, Maarten van Heemskerck, Dirck Barendsz, Karel van Mander, Hendrick Goltzuis, Pauwels Frank/Paolo Fiammingo and Ludwig Toeput/Ludovico Pozzoserrato all created unique dance images. I, for one, am curious to learn how they illustrated dance, and how they were influenced by the Italian masters.

One of the earliest Dutch artists to travel to Rome was Maarten van Heemskerck (1498-1574), a contemporary of Pieter Bruegel the Elder. He remained there from 1532 to 1536/7, fascinated by ancient Roman architecture and sculptures. He even portrayed himself, larger than life, next to the Colosseum.

Self-portrait, with the Colosseum, Rome – 1553 – The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

Apollo and the Muses – oil on panel – 98cm x 136cm – 1555-60 – New Orleans Museum of Art

Van Heemskerck’s mythological painting, Apollo and the Muses, depicts Apollo and his muses in two separate moments. In the foreground, Apollo, playing the lyre, rests with his muses, and on the hilltop he leads his gracious muses in a circular dance. It is feasible that van Heemskerck, a guest in Renaissance Italy, was familiar with Baldassare Peruzzi’s work Apollo and the Muses (1514-1523), and possibly acquainted with the exquisite dancing figures rendered in Andrea Mantegna’s Four Women Dancing (c. 1497) and Leonardo da Vinci’s Three figurative studies of dancers and study of a head. (c.1515)

In Apollo and the Muses, the artist traverses time, blending various periods of Roman culture. For instance, the mythological figures are shown playing a combination of ancient and Renaissance musical instruments, and some of the muses are dressed in archaic Roman drapery while others are in fashionable Renaissance dress. And what to make of the disrobed muse reading a music score written in book form; a diverting anachronistic witticism? Where this painting subtly suggests an ancient Roman sphere, the prints that van Heemskerck created for various albums are decidedly rooted in Roman heritage. Many of these prints have been passed down by way of etchings, reproduced by print-makers/engravers Philips Galle and Harmen Jansz. Muller.

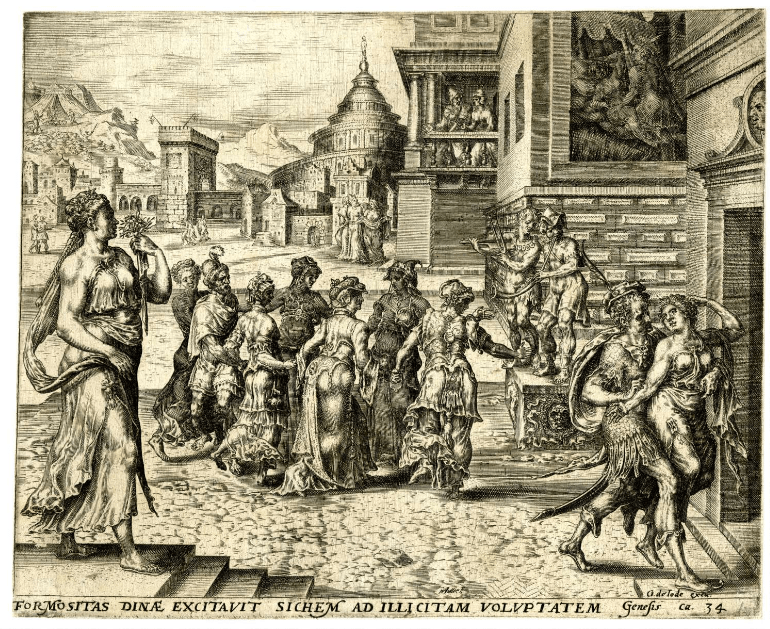

The Story of Dinah and Shechem ( print from a series) – Etching by Harmen Jansz. Muller – c.1569 – British Museum

The Slaughter of the Fattened Calf (The Prodigal Son series) – Engraving by Philips Galle – 1562 – Rijksmuseum

The prints, both after Maarten van Heemskerck, recount the biblical story of Dinah and Shechem (Genesis 34) and the slaughter of the fattened calf from The Parable of the Prodigal Son. The two circle dances, though similar in form and locomotion, differ in setting and context. In The Story of Dinah and Shechem, the dance is positioned in the centre of the illustration; only Dinah, entering the city of Shechem, towers over the dancers. The women are all meticulously dressed. The artist has left no detail to chance; the gowns are adorned with buttons, sashes, and jewels. Oddly, though, the robes appear to swing freely, giving a metallic effect, not unlike armour. These muscular dancers are quite the opposite to the softer, less robust, almost medieval dancing figures celebrating the prodigal son’s return home. The mild-mannered dancers and the other figures familiar from the parable are allotted a secondary position; the butchers and the enormous hanging carcass claim prominence. The composition is divided into three layers, with the dancers being placed snugly between the stairs and the elevated plateau. How the company dances is naturally speculation, but if the men’s varied footwork and leg rotations provide any indication, the dance is likely to be fairly intricate. This pleasant round dance conveys the joy of the son’s return; in contrast, the dancers accompanying Dinah are startled, not to say apprehensive, their dance being abruptly interrupted by the uninvited Shechem.

Common to both works is a striking Roman setting; note the architecture distinguished by arches, domes, balconies, columns, and capitals. The doorway under which Shechem abducts Dinah displays a typical Roman medallion. All the figures are sturdy and muscular; Dinah, holding flowers, has pronounced shoulder muscles and robust legs, and the butcher and his assistant are no less strapping. The structure of the muscles, up to and including the buttocks and torso, is emphatically rendered. Michelangelo’s sculptural anatomical delineation was unquestionably an inspiration for van Heemskerck, as it was for the Flemish printer, draftsman, and painter Hendrick Goltzius (c.1592-1617). One glance at his powerful sketch, the Farnese Hercules, is sufficient to attest to his admiration.

Goltzius, to my knowledge, did not compose any specific dance images(2), although he produced The Four Disgracers, a group of astonishing kinetic figures in collaboration with the painter Cornelis Cornelisz van Haarlem. Goltzius did, however, engrave a masterful dance image, The Venetian Wedding, based on a drawing provided by an early visitor to Venice, the artist Dirck Barendsz (1543-1592). Barendsz travelled to Italy at the age of twenty-one, working for the most part with the eminent Venetian artist, Titian. He stayed there for seven years before returning to Amsterdam, to become an influential artist, introducing Italian art to his northern contemporaries.

Pen in brown, brush in blue; grid in black chalk on the left-hand half , Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

There are a number of different interpretations of The Venetian Wedding. The majority of art scholars, however, suggest that the scene commemorates the wedding of Titian’s daughter, even proposing that the bearded old man on the right is Titian himself.

The scene is set in a Venetian atrium, with an outstanding view of the islands and the boats sailing on the lagoon. Commedia dell’arte figures and musicians entertain a company of splendidly dressed gentry, amusing themselves in conversation and, in some instances, coquetry. The bride, with loose flowing hair, and groom are flanked by two dignified couples. The elegant couple in the centre appear to open the ball, taking the lead in a slow, refined, promenade dance, possibly a bassa danza. As is common in Renaissance dance, the woman’s posture is slightly inclined backwards, giving an accomplished curved impression. The gentleman presents himself stylishly, exercising great care to position his feet and legs precisely as instructed by the fashionable Italian dance masters who taught dance and etiquette at court.

Similar elegant dancers feature in the work of two Flemish artists, Pauwels Franck (c.1540-1596) and Lodewijk Toeput (c.1550-1603). Both exchanged Flanders for Venice and the surrounding area, Italianizing their names to Paola Fiammingo and Ludovico Pozzoserrato, respectively.

An Allegory of Venus and her Planet Children conveys the onlooker to a majestic ballroom where a hovering cloud, practically covering the top half of the canvas, is occupied by mythological figures. Four musicians, painted in darker tints, accompany a formal, refined promenade dance executed by the most elegant of couples. The ladies, reminiscent of the Barendsz drawing, are elaborately dressed, and, as the then contemporary dance technique demanded, slant in a gentle backward curve, pushing their pelvises slightly forward. The gallant partner is an accomplished dancer. His precise foot placement and the carriage of his arms demonstrate his extensive dance training. It is evident that the aristocracy and elite enjoyed dancing lessons from an early age; the two children promenading in the foreground show an elegance and deportment that can only be acquired by formal training.

Ludwig Toeput’s painting, The Concert, is more than an attractive painting about music and dance. The scene presents a Venetian woman, groomed in a fashionable horn-shaped hairstyle, playing a Renaissance keyboard. She is accompanying a suave lady dancing next to a smartly attired man. It is apparent that they are not performing a dignified bassa danza. Rather, the man is executing a sprightly dance, demonstrating his proficiency with low leg extensions and quick jumps. A closer look at the painting reveals some interesting clues — a bedstead, inseparable couples, and a dressed monkey — as to the purpose of the man’s dance. Toeput unveils an opulent chamber, a residence for charming courtesans.

Salome dancing during the banquet of Herod – Jan Saenredam after Karel van Mander – engraving – 265mm x 408 mm – 1589-1607 – Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

The last two artworks are practically identical. The elegant Venetian dancing couple are the centre of attention. The young woman carries herself with dignity, lowering her head gently and casting her eyes modestly downwards. She delicately holds her skirt between her thumb and index finger. Karel van Mander has even accented this gesture; she politely extends her middle finger. Her equally elegant partner dances with fitting élan, lunging slightly backwards as he fastidiously extends his leg effortlessly to the front; the movement resembles a ballet position. This Renaissance court dance is accompanied by a young lute player, seated at the far left. The scenes, though so alike, are rather different in context. The guests at the Toeput table include, among others, a king, a condescending individual wearing a sort of green doge’s cap and some Eastern gentlemen. Comparable figures appear at Van Mander’s feast. But where Toeput’s work is open to various interpretations, ranging from a piquant artwork ideal for a gentleman’s drawing room to, as has been suggested, a biblical tale relocated to a Venetian setting(3), van Mander illustrates the Old Testament story of Salome. In the niche, situated in the upper right corner, the executioner is shown beheading John the Baptist.

Which artist, you may ask, rendered the original work? I have not been able to precisely date either work. I do know that Toeput is believed to have arrived in Venice around 1573-74, and that Karel van Mander apparently met him there. The artists must have been acquainted with each other’s work. Toeput’s style, as seen in formal garden, banquet and music paintings, is definitely akin to Scene of a Feast. If van Mander emulated Toeput’s work, a further question would need to be asked. For the record, we only know van Mander’s Salome from an engraving produced by Jan Saenredam (1565/6-1607). The name Karel van Mander is inscribed on the engraving giving him credit as the designer, but, did Jan Saenredam add any additions of his own? Saenredam never travelled outside of North Holland, therefore we can reasonably assume that the engraving was made in The Netherlands. The question as to which artist created the original work still awaits an answer. But, however interesting these facts are, the question of who inspired who is not the most intrinsic issue. Of greater significance is that artists of The Low Countries travelled to Rome and back, exchanging heritage, ideas, and techniques with their Southern peers, absorbing the many facets of Italian art to mould an artistic culture in which northern and southern European art flourished.

1 – Paul Bril was primarily a landscape painter. The figures in his paintings were, at times, painted by another artist. I have not been able to ascertain if this is the case in Mythological Landscape with Nymphs and Satyrs

2 – I wrote that Hendrick Goltzius, to my knowledge, did not compose any dance images. Though not primarily a dance image, there is a couple dancing in the background of the print, The Banquet of Sextus Tarquinius.

3 – My thanks to AnticStore where I found the suggestion that Toeput’s painting maybe a scene from the Old Testament transposed to the Renaissance.