Inspired by the great Italian masters of the Renaissance, artists of The Netherlands travelled to Rome, the unchallenged home of art. Maarten van Heemskerck, Karel van Mander, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Hendrick Goltzius, and Peter Paul Rubens all ventured the hazardous journey to the south, as did many 17th century artists. These latter Flemish and Dutch artists formed a brotherhood, the Bentvueghels. This unbridled society of non-Italian artists was established in the 1620s and continued until it was disbanded in 1720 by order of Pope Clemens XI. The Bentvueghels, a rowdy group, infamous for their toga clad initiation ceremonies, excessive drinking and for endowing their members with mocking nicknames were, regardless, prolific artists inspired by Roman countryside, southern landscapes and above all the vibrant Mediterranean light.

One of their members, Pieter van Laer, nicknamed ‘Il Bamboccio‘ which translates as ‘ugly doll’ or ‘puppet’, was the first Netherlandish artist to paint street scenes featuring ordinary Roman people in everyday situations. He, recognized as the initiator of the Bamboccianti style, introduced Flemish and Dutch genre art to Rome, integrating down-to-earth subjects into the traditional Italian style. He, his friends, and peers, known as the Bamboccianti, focused on peasants, scoundrels, beggars, milkmaids, soldiers, tavern scenes, and dancers; popular subjects in 16th and 17th century Netherlandish genre art.

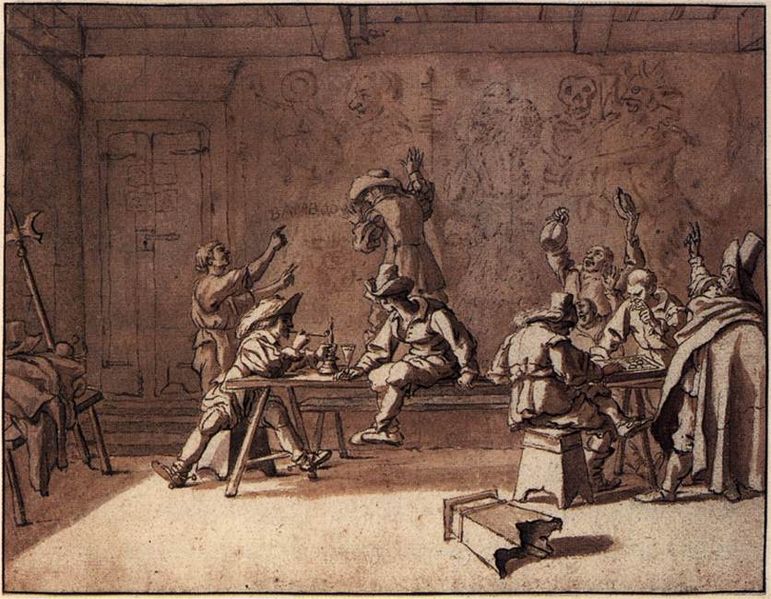

Under the arcades of Roman ruins, Pieter van de Laer stages an atypical Italian drawing. Commonplace people are talking, eating, drinking and generally relaxing. Similar figures to those featured in the above tavern scene appear in this drawing. These are the Bentvueghels enjoying a pleasant siesta under the shade of some ancient vaults. Moving towards the wall, just behind the men sitting at a table, there is a group of musicians playing on an elevated platform. And in the centre passage there is a couple performing a lively dance, clapping the beat of the music and juggling from foot to foot, which, looking at their strapless clogs, is no easy feat. The male dancer appears distracted, shifting his focus to the two anomalous figures conversing with each other. These, no doubt, are the Netherlandish artists, whose offbeat habits and idiosyncrasies have aroused curiosity.

The initial Bamboccianti were Andries and Jan Both, Karel Dujardin, Jan Miel, Johannes Lingelbach and the Italian artist Michelangelo Cerquozzi. A later generation included Dirck Helmbreker, Anton Goubau, Willem Reuter, and Jan Asselijn, the latter famous for his overwhelming painting the Threatened Swan. Asselijn, to my knowledge, never painted dancers. This post will concentrate on the dance images created by the first wave of Bamboccianti.

Jan Both specialised in landscapes, but his brother Andries Both (1612/3 – 1642) painted genre pieces, scenes from everyday life featuring the lower classes of Rome. His brothels, card players, tooth drawers, travellers and tavern scenes expose the shadier side of Roman life. In The Netherlands, Adriaen Brouwer and Adriaen van Ostade painted similar subjects. The influence of Caravaggio is not to be mistaken; Andries Both, as the Italian master, plays with gripping, often theatrical lighting to achieve remarkable effects. In The Hornpipe, a bright spotlight illuminates the main characters; in Lice Hunting, an extraordinary genre piece, the contrast between light and dark is dramatically striking.

With a title like The Hornpipe, you might expect a sailor dance. True, the hornpipe is a traditional dance often associated with sailors in smart white uniforms. This is certainly not the case in The Hornpipe, one of Both’s more cheerful works, that features a man dancing in the courtyard of a humble tavern, surrounded by an old rustic wrapped in a shabby cape, a man who only has eyes for the woman next to him, a drinking couple and a peasant playing a pipe. Admittedly, the dancer is light-footed tackling typical hornpipe movements, like jumping or hopping with uplifted legs. But apart from this very general dance movement, there is little in Both’s painting that indicates a sailor dance. This is not surprising, since long before the dance became associated with sailors, the term hornpipe either referred to a musical instrument consisting of wooden pipes with spaced holes and mouthpieces made of horn or a jovial dance performed to a brisk tune played by a hornpipe.

The Hornpipe, a genre piece, is set in a typical Roman architectural setting. The dancing figure and his seated companion distinguish themselves from the simple peasant figures with their well-tailored attire; take note of the elegant row of buttons decorating the jacket and their spotless collars. These men cannot be the regular tavern clientele. They are presumably casual guests enjoying a drink. Prompted by the musician’s melody and no doubt the drink, one of the men wholeheartedly performs an impromptu dance.

Karel Dujardin (1626-1678), a Romanist, was equally proficient in painting portraits, religious paintings, landscapes, and genre pieces. He was a member of the Bentvueghels, nicknamed Barba di Becco (goatsbeard) and a prominent Bamboccianti, painting pastoral scenes of peasants, shepherds, and animals, as well as street scenes depicting travelling performers from the commedia dell’arte to wayfaring musicians. In the following small genre works, Dujardin describes two moments in the lives of youngsters and their dog, entertaining a group of peasants with music and dance. Possibly Dujardin actually saw these street artists performing, considering that the dancing lad capering in Two Travelling Musicians, appears in both paintings, as does the smaller youth playing the fiddle. The third figure, a boy playing a violin, only appears in one painting. To whom is he looking? Perhaps his glance is directed at the artist, whom I would like to imagine is resting in the tavern. His expression, whether directed at the artist or at the spectator, is thoroughly delightful, drawing the viewer immediately into the picture. In the right painting, the artist introduces another new figure. This jolly fellow, with the red kerchief, improvises a little dance, flinging his leg randomly to the back. He is either cheerful or rowdy, or both, as he not only receives the undivided attention of the woman seated near the barrel but also invites the curiosity of the woman peering from behind the curtain.

Left: Two Travelling Musicians – oil on canvas – 51 x 46.5 cm – private collection

Right: Boys dancing and making music in front of a tavern – oil on canvas – 36 x 47.50 cm – private collection

In his early years the Flemish artist Jan Miel (1599 – 1664), a follower of Pieter van Laer, was a member of the Bentvueghels, and subsequently the Bamboccianti. He was fittingly nicknamed, Honingh-Bei (honey-bee). Miel was well known for genre paintings as well as animated Roman Carnival pieces, which often included the personages of the Commedia dell’arte. Later in his career he turned to historical subjects rendered in the classical style, assuming the role of court painter for Charles Emanuel II, Duke of Savoy.

Dance in the Trattoria, one example of Miel’s carnival works, unites a Roman street scene with typical Dutch and Flemish traits. The architecture, the figures, and the folklore are definitely Roman, but the right side of the painting, showing day-to-day scenes like housewives performing menial duties, is inherent in Dutch and Flemish genre painting. These insignificant activities, anchored in Dutch and Flemish art, were obviously dissimilar to the more lofty subjects rendered in 17th century Italian art. And is there anything more distinctively Dutch than the still-life of pots, pans, and jugs in the lower right corner?

The painting introduces various archetypal figures of the Commedia dell’arte, Il Dottore, Scaramouche, the Innamorati, Columbine, Harlequin, and other zanni, singing, dancing, and drinking outdoors. Near the centre of the scene, Trivellino, a zanni, plays a string instrument. Meanwhile, Harlequin is enjoying a glass of wine, and Scaramouche, a figure recognizable by his black mask and clothing, dances with Columbine. This unique couple stands side by side, most likely dancing a saltarello. The saltarello, a dance full of jumping movements, was the most popular Roman dance during carnival time. The recurring step and hop movement, that Scaramouche performs, is one of the characteristic steps. And by giving the lovely lady in yellow a tambourine, Miel offers another clue; this instrument usually accompanied the saltarello.

The only aspects that differentiate A Village Festival, Peasants Merrymaking outside an Inn from a Dutch or Flemish peasant scene are the undulating landscape, the southern architecture, and the bright blue skies. The men lounging around the tavern, the lovers near the table, the beer filled jugs lying on the ground, the bagpipe player, the drummer, and the dance around the maypole are all decidedly familiar. Many 16th and 17th century Dutch and Flemish painters composed paintings using the same components; the village scenes by the Flemish artist David Teniers the Younger (1610-1690) and the Dutch artist Jan Steen (1626-1679), to name but two artists, are world-famous.

The artist who painted this village scene, Johannes Lingelbach (1622-1674), was German by birth, moving to Amsterdam as a youth. He travelled to Rome in 1642, becoming a member of the Bamboccianti. Dance and dancers regularly appear in his works. This village scene blends two schools of art. Lingelbach has woven a northern narrative within a southern ambience. The vivid blue sky with a mere spattering of clouds, the rolling hills, and the characteristic southern homes with small windows are definitely Mediterranean. The peasants gathered around the table, however, as the two musicians, a bagpiper and flute/drummer, have their roots in Dutch and Flemish painting. The two artistic visions interact seamlessly, but it is the lovely maiden in blue, raised on a wooden cart, that catches all the attention. She is the only figure in the painting clad in an effervescent colour. Her blue dress blends delicately with the pastel shades that Lingelbach has chosen for the landscape and sky. She, the May Queen, joyfully jingles the tambourine for the village folk dancing around the maypole.

Art inadvertently influences art; Pieter van Laer inspired the Italian painter Michelangelo Cerquozzi (1602-1660). He became a Bamboccianti, painting, like his northern peers, small paintings of the ordinary man in commonplace situations. The painting shown below, simply called Bamboccianti is indebted to Dutch and Flemish village scenes. Cerquozzi adopted the Bamboccianti style and adapted it within a Roman/Italian setting.

The dancers practically occupy the entire right half of the painting. The smiling couple are vivacious movers. They hop, jump, twist, and turn zealously. You can almost anticipate the following movements. Their frolicking folk dance, perhaps a tarantella, amuses both onlookers and the musician.

The exchange of artistic visions, techniques, and styles is an ongoing process. The Bamboccianti opened new avenues inspiring Italian artists, just as Italian art inspired the many Dutch and Flemish artists who visited Rome, the ‘unchallenged home of art’.