Apart from the two little girls in the foreground, preoccupied with their red and white stripped tooters, everyone surrounding the brazen centre figure is riveted by her outrageous dancing. Piet van de Hem (1885-1961), an artist who recurrently painted dance images, instantly draws the onlooker into the performing area, highlighting the bulky, earth bound dancer. She dances forcibly, flexes her knees vigorously, protrudes her crude bottom, and sticks her graceless arms outwards. She, with a far from cordial expression, looks directly at the viewer, inviting one and all to join in with the celebrations. The musicians, one playing the drums and the other an accordion, attentively follow the rhythm of her flashy movements. One glance is enough to discover that these festivities take place on a warm summer day; washing on the line, no overcoats, and children with short-sleeved smocks. And all this is rendered against a rose-coloured façade, in a luscious array of pastel colours with just a touch of red to underscore the girl’s dresses and the festive balloons. Van der Hem, well known for his painting of day to day life of ordinary people, unveils a traditional Dutch folk festivity, known as Hartjesdag.

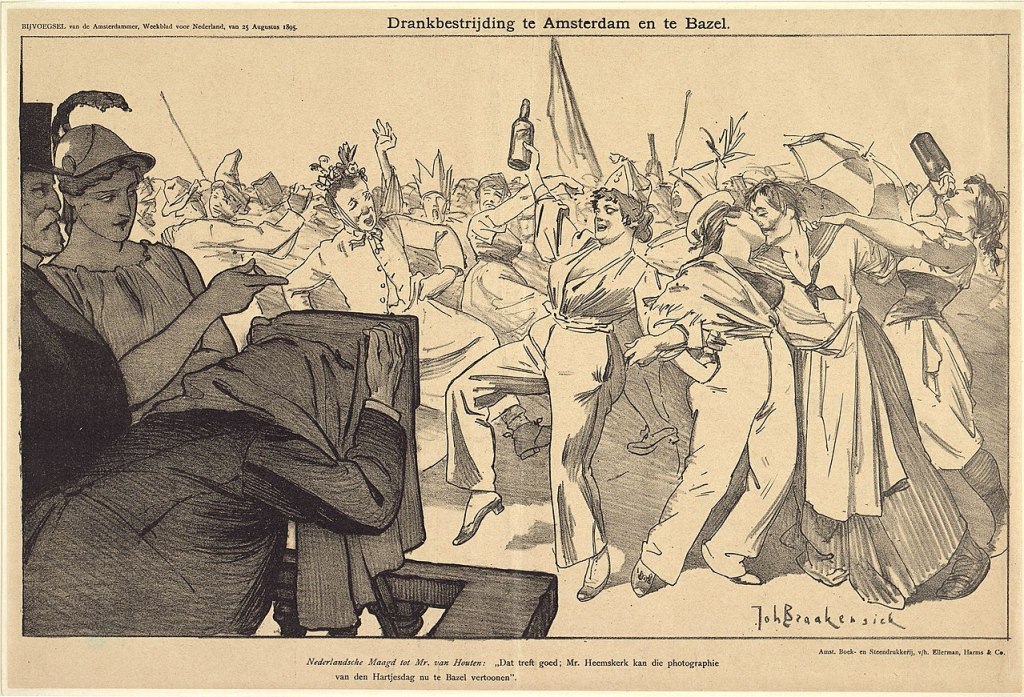

Hartjesdag, a festivity once celebrated on the third Monday in August in Amsterdam and Haarlem, originated in the Middle-Ages. The sphere was carnivalesque, men dressed as women, women dressed as men, fireworks abounded and alcohol flowed freely. Rowdiness and misconduct were commonplace, no doubt exacerbated by excessive use of alcohol. In 1895, Hartjesdag became the subject of a cartoon by the prolific artist Johan Coenraad Braakensiek (1858-1940), a popular illustrator, graphic artist and painter. He designed discerning cartoons for De Amsterdammer, a newspaper published from 1882-1895, frequently calling upon The Dutch Maiden (De Nederlandse Maagd), the national personification of The Netherlands, to voice social and political opinions. In the following cartoon, Braakensiek exposes the tumultuous hustle and bustle that takes place on Hartjesdag, punctuating the intemperate drinking of the revellers. The Dutch Maiden, unmistakable in her iron helmet, discusses anti-drinking strategies with a government official as the high-spirited town folk, dance, kiss, make merry and drink copiously.

Braakensiek revisited the newspaper cartoon thirty years later, transforming the original print into a large painting of a street scene, set in the centre of old Amsterdam. The most prominent figures and numerous background figures, merely sketched in the print, reappear as fully established personalities. The eye-catching, jovial female may have exchanged her beer bottle for a party horn blower, but she still dances vigorously. Her partner, as in the cartoon, having slipped into a skirt, reciprocates her leg lifting antics. A third dancing figure, a relatively older man, steps and shuffles, waving his arms effortlessly, replicating the compelling rhythm of the trumpeters playing a little to the back. Just behind the open-mouthed, wide-eyed, jubilant woman is a couple, also depicted in the original print, dancing to the jiggling chimes of the tambourine. Not in the original print is the bizarre farcical smile of an unrecognisable man in a top hat that emerges at the junction of the couples’ clasped hands. The painting is brimming with dancers, revellers and spectators; though not dancing, it is worth mentioning that the familiar kissing couple have traded clothes, the bier drinking woman is now bare breasted, and that the couple of old dears watching the bedlam are none too happy. There is, furthermore, a police officer on watch, standing, or so it seems, directly under the pronounced bosom of the woman leaning out of the hotel window.

Jacobus van Looy (1855 – 1930), writer and artist, adopted a different approach to Hartjesdag, presenting an evening scene illuminated by a then recent invention, the electric light. The primary source of light radiates from the left corner, enabling the viewer to obtain a reasonable impression of the people watching what surely must be a Punch and Judy show. Striking is the two somewhat illuminated couples who cling to each other affectionately in a swift whirling dance; the soaring skirts attest the dancer’s momentum. Of the third dancing couple, only the free-flowing skirt is visible, Van Looy having obstructed a direct view by planting a sturdy motionless woman in the foreground. The couples whirl and spin endlessly, but except for the trumpet that Punch is blowing, I have not, as yet, discovered an instrumentalist. Yet, there is definitely a musician somewhere in the crowd. Van Looy, in a verse written in 1895, mentioned this specific scene, explaining that an organ man, if given a few pennies, never tires of grinding his organ. He further reminisces that in the light of the street lanterns silhouettes shift, turn, and sway, to the irresistible melody of a waltz, played by the organ man.

Orange is the Dutch royal colour; annually the Dutch dress-up in orange garb to celebrate the national festivity, the Feast of Orange. Van Looy’s orange tinged painting, shown below, is his not particularly pleasant impression of the night-time festivities surrounding the seventieth birthday of the Dutch King, Willem III in 1887. The artist recalls, that roaming through the streets of Amsterdam, he was dumbfounded by the singing, the yelling, the dancing, the light of the street lanterns, the fireworks, and above all, the disarray of orange.

Jacobus van Looy – Oranjefeest – c. 1890 Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

There is no way of escaping that cluster of orange in the centre of the painting. Neither can you miss the brightly coloured lantern held aloft by the jubilant woman. The woman in orange bloomers practically falls backwards; she commands immediate attention. She is plainly oblivious of the outside world, evidently drunk, and sings at the top of her voice. The artist is under no circumstances complimentary; he brazenly illuminates her face, exposing her excessively open mouth and her explicit nose. At her side, though not obvious at first sight, a second woman runs straight towards the onlooker. She, no less than her festive companion, is hideously portrayed. In Oranjefeest, van Looy evokes his encounter with the drunken women, the orange cheeriness, the crude yelling and the unrestrained pandemonium.

Herman Braakensiek (1891-1941), nephew of the celebrated Johan, was an avid traveller, interested in and influenced by contemporary art styles. His painting, Jordaan, illustrates the currently fashionable area in Amsterdam that historically was a working-class neighbourhood, known for conviviality and merriment but also for intemperance and ribaldry; exactly the elements encountered in this innovative work.

Where to start? There are so many figures, colours, interwoven shapes, angular and curved lines, and varying viewpoints. Braakensiek simultaneously presents a bird’s eye view of a street festivity and a frontal view of dancers, a dog, and houses. This cubist influence is developed throughout, as is the narrative, displaying modern life in the 1930s; the most obvious example being the short haircuts of the kissing women in the left-hand corner. Typically Dutch is the barrel organ, illustrated here, as an oblique slope decorated with a slim-waisted doll-like figure further highlighted with red boobies. The organ grinder, a dark figure standing next to the organ, appears to have stepped out of a work by Picasso.

Street organ music invariably invites dancing. It is evident that this organ is playing a brisk, cheerful melody; the two brawny, brown figures delight themselves in dancing an animated hornpipe. They bounce or hop from foot to foot, flexing their ankles with each switch of the feet. They, even more than the other figures, are geometrically shaped, resembling a toy robot. In contrast, the charming dancing couple in the right foreground, though stylised, dance elegantly in ballroom fashion. That cannot be said of the hunky sailor, performing undefined leg and arm movements. To his right, another dancing couple rush in, though there seems to be little space left for them to dance, the entire dance area being enclosed by a semi-circle of spectators. The figures, whether a dancer, a spectator, or the man sitting behind the window sill smoking a pipe, are rendered in a semi-abstract fashion. All the faces, except for the gentle lady peeping around the more traditional dancing couple, are rough, better said blotchy. In this atypical Dutch painting, Henri Braakensiek, has embraced the latest art styles of his day, convincingly reproducing the social environment of the Jordaan in the 1930s.

Paul Nieuwendijk – Koningsdag vieren oranje feest op gracht Amsterdam / Celebrating Kings Day, orange feast on a canal in Amsterdam) – acrylic on panel 50x 40 cm – 2013 EXTO)

To return to Hartjesdag; for centuries, revellers flocked to the streets dancing, drinking, and making merry. In 1943, during the German Occupation, the celebrations were banned. Under the enterprising effort of the Zeedijk community committee, Hartjesdag enjoyed a come-back in 1997; the annual festivities include a flamboyant parade spearheaded by members of the LGBTQ+ community. The above photo of the 2007 parade, flaunts the performance artist, the living artwork, Fabiola (1946-2013). Hartjesdag today is as high-spirited as in the past, preserving long-established traditions. The same applies to the Orange Feast, a feast celebrated on the occasion of the sovereign’s birthday. The contemporary Dutch artist, Paul Nieuwendijk, commemorates the festivities in an impressionist painting where the colour orange upstages all others. Jacobus van Looy may have been dumbfounded by the disarray of orange, but Paul Nieuwendijk celebrates orange, the national colour of The Netherlands.

* In the The Digital Library for Dutch Literature (DBNA) the writings and paintings by Jacobus van Looy are discussed and at times, reproduced. The text is in Dutch. On page 25 you will find information about both the painting and the text concerning Hartjesdag. Below, the text which I have referred to.

Hier zitten de kijkers of zaten ze er honderd jaar […] Voor zooveel centen wordt de orgelman niet moe […] telkens vervat hij den slinger met een uitgeruste hand. Hij laat de paren dansen, die elkaâr bij de schouders houden, want veel danst meid met meid. En hun voeten kennen de keien; hun gedaanten, verstompende in den schemer, die altijd tusschen lantarens is, schuiven, keeren, weêrwiegelen het heete leven van den wals.

Van Looy in het Tweemaandelijksch Tijdschrift, januari 1895, 335.