For the non-dancers amongst us, the name Loïe Fuller may not ring a bell, but feel assured, you have encountered several images of this extraordinary trailblazing American dancer. Loïe Fuller (1862-1928) revolutionised dance. At a time when ballet was in decline and the dancers at the Moulin Rouge and Folies Bergère performed the voguish Can Can, the innovative Loïe Fuller, who was based in Paris for the greater part of her career, totally transformed the concept of dance. Contrary to the conventional dance style, Fuller emphasised arm and torso movements. She ‘elongated’ her arms with long bamboo rods that were concealed beneath meters of billowing silk. She reeled and rotated the two lengthy rods, manoeuvring these extensions into phantasmal shapes. Equally groundbreaking were her experiments with colour and her pioneering exploration in hitherto unprecedented theatrical lighting. She mesmerised her audience. La Loïe, as she was proclaimed in Paris, was the embodiment of the Art Nouveau. In her biography ‘My Life’, Isadora Duncan, the other leading pioneer of modern dance, vividly reflects the genius of Loïe Fuller.

Before our very eyes she turned to many-coloured, shining orchids, to a wavering, flowering sea-flower, and at length to a spiral-like lily, all the magic of Merlin, the sorcery of light, colour, flowing form. What an extraordinary genius.

That wonderful creature – she became fluid; she became light; she became every color and flame, and finally she resolved into miraculous spirals of flames wafted toward the Infinite.

Isadora Duncan – My Life

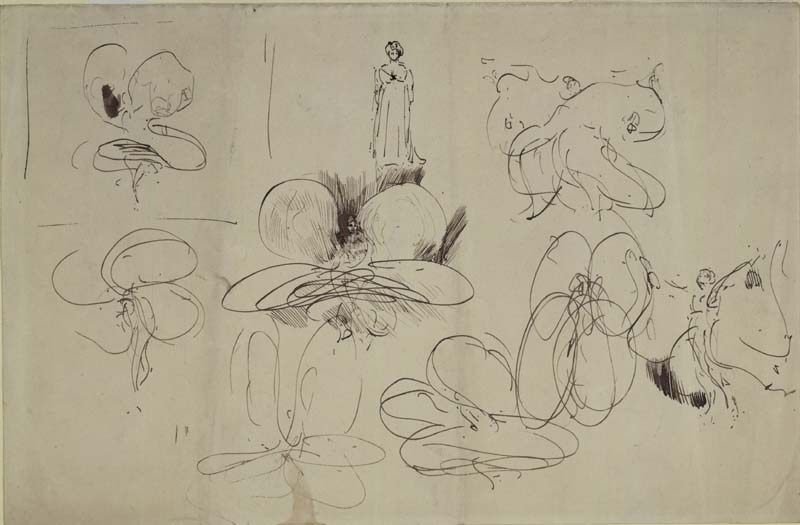

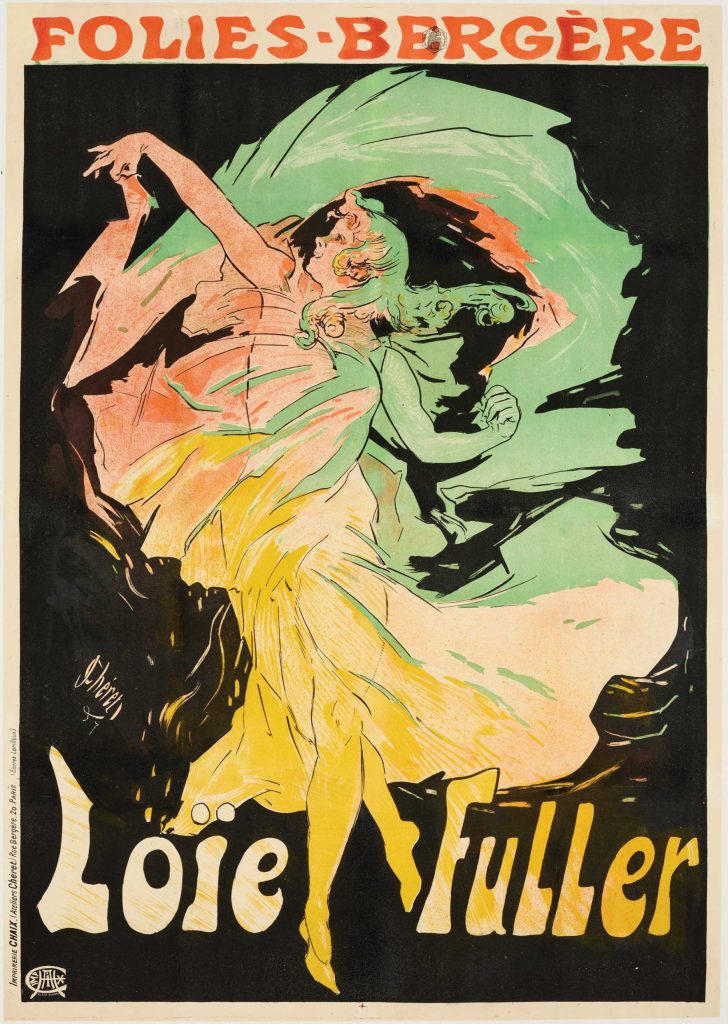

From her earliest performances at the Folies Bergère and throughout her career Fuller, the darling of the Art Nouveau, unceasingly inspired writers, poets, sculptors, visual artists, jewellery designers and photographers. The cylindrical advertising columns, so characteristic in the Parisian streets, were adorned with riveting, multicoloured posters of La Loïe, by Jules Chéret, Pal, and Toulouse-Lautrec. Renowned sculptors, among them, Raoul Larche, François Rupert, Pierre Roche, and Théodore Riviere created statutes, lamps, vases and other objects d’arts highlighting Fuller enclosed in gracefully flowing drapery. The great Rodin fell under her spell, and she captivated the acclaimed American artist, James Whistler, as the above pen and black ink drawing lovingly conveys.

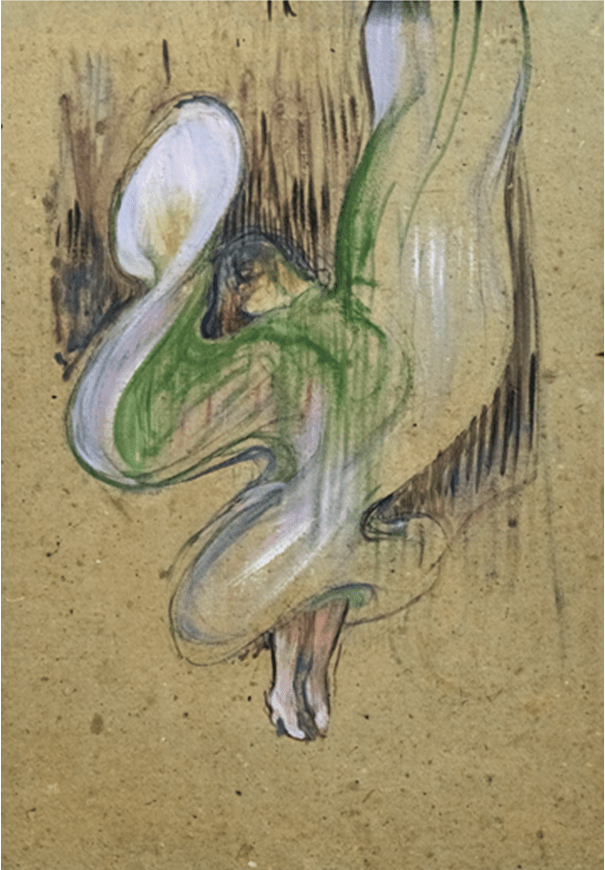

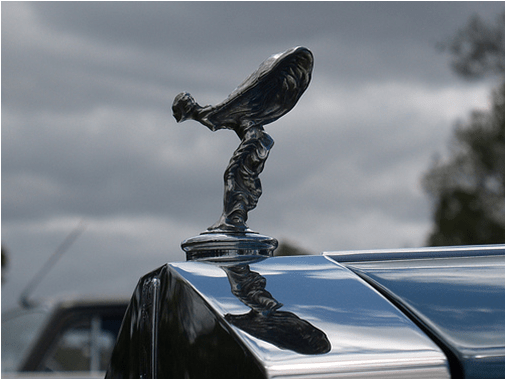

Whether you are acquainted with the name Loïe Fuller or not, chances are that the following three images will be familiar. Chéret’s wonderful design is legendary, exploited by merchandising with products ranging from posters to cookie jars. Toulouse-Lautrec’s design shares a similar fate, though the small statuette created by Charles Sykes is reserved for the more affluent. The figure, you will recognize, is the Rolls-Royce radiator mascot. Common to these works and all the artworks are the whirling, spiralling, voluminous fabrics often totally encircling Fuller, where she, the dancer, is entirely shrouded within the undulating cascade of their continual motion. La Loïe, immersed in her overwhelming costume, evolves into an organic whole.

La Loïe Fuller aux Folies Bergère – Toulouse-Lautrec – 1893

Charles Sykes – Mascotte radiator Rolls Royce, The Flying Lady (or Spirit of Ecstasy) – bronze – 1911

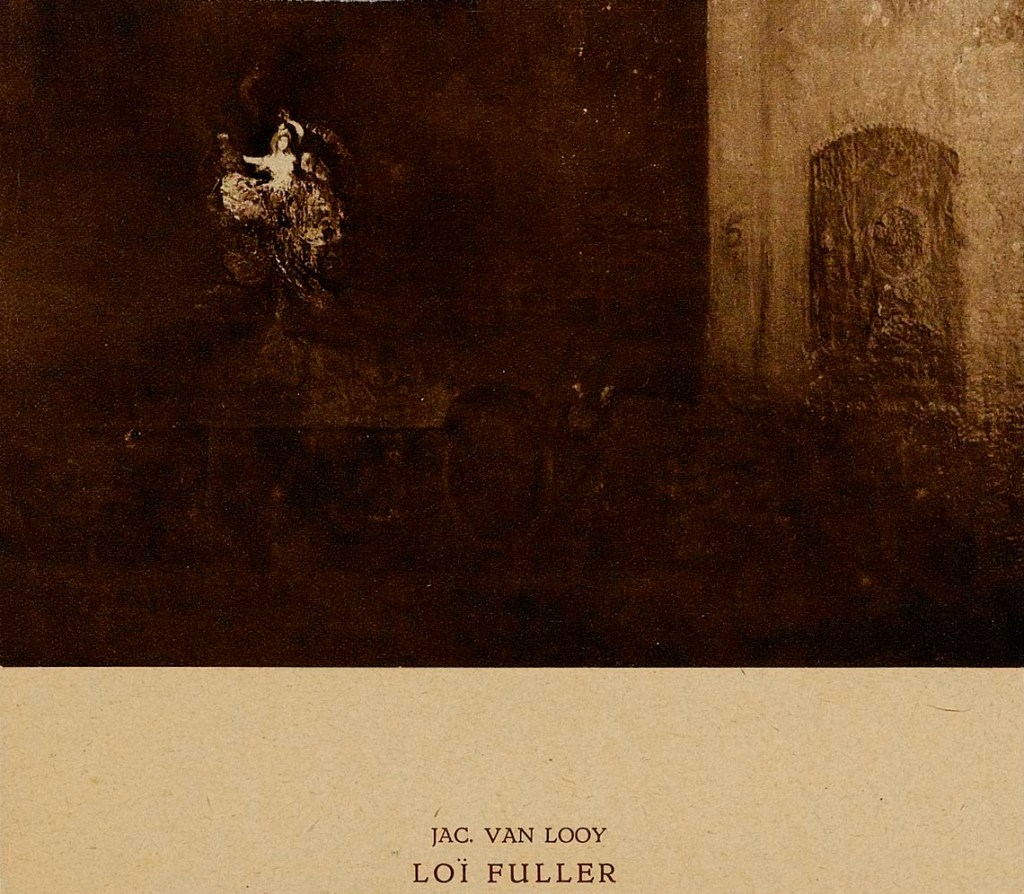

Loïe Fuller and her company travelled extensively throughout Europe and America. She visited Belgium various times but, as far as I could discover, rarely visited The Netherlands. This may explain why, though she inspired a myriad of international artists, I could only find a handful of works by Dutch and Belgian artists. In her autobiography Fifteen Years of a Dancer’s Life (f.p. 1908) Fuller recounts a ‘in every way a very successful’ gala evening in The Hague, where she was asked to perform before the Grand Duke and Duchess of Mecklenburg. A chronological overview of Alphons Diepenbrock’s life and work informs us that the esteemed composer, accompanied by his wife and other family members, attended a performance featuring Loïe Fuller in March 1898. The show took place in The Netherlands, but the venue is not stipulated. Where the artist/author Jacobus van Looij saw Loïe Fuller dance is unknown; perhaps in Amsterdam, but just as likely in Paris. Van Looij, about whom I wrote in two earlier posts,* was an avid traveller, painting various dance-related works. The image, illustrated below, is a black and white photograph depicting one of the sparse Dutch paintings, regrettably destroyed in 1945, celebrating Loïe Fuller.

The painting places the artist, Jacobus van Looij, somewhere in the stalls, sitting behind a man whose head he has vaguely outlined. Nearer to the podium, a few faces are illuminated by the stage lighting. Fuller, herself, poses in a multitude of light. She poises in mid-air, hovering weightlessly on an otherwise dark stage. Fuller defies gravity. Van Looij’s lost painting, preserved in photographic form, captures the undeniable magic of Fuller’s memorable transformation.

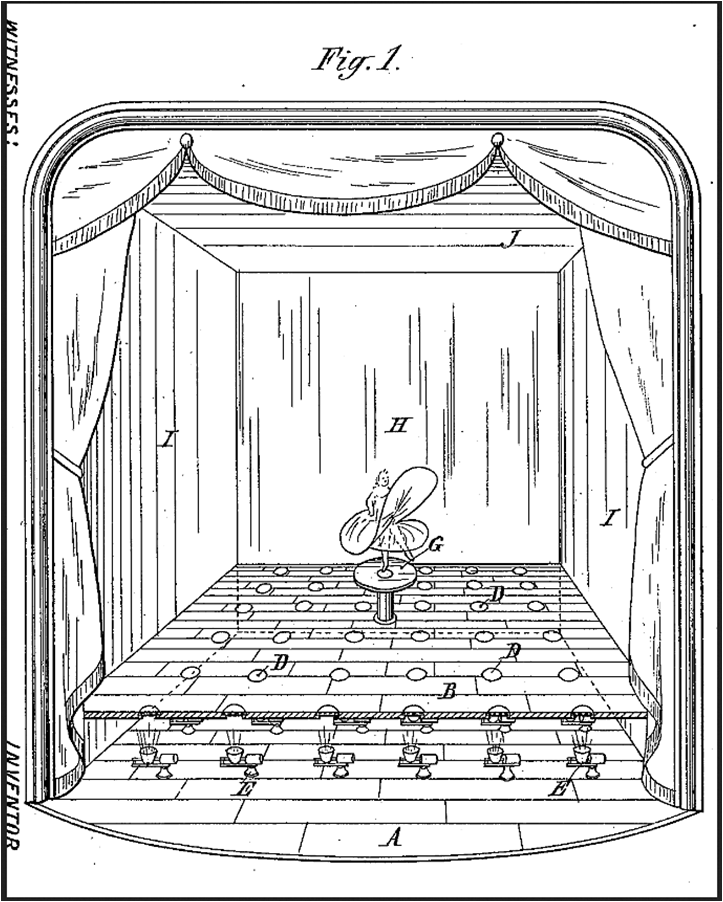

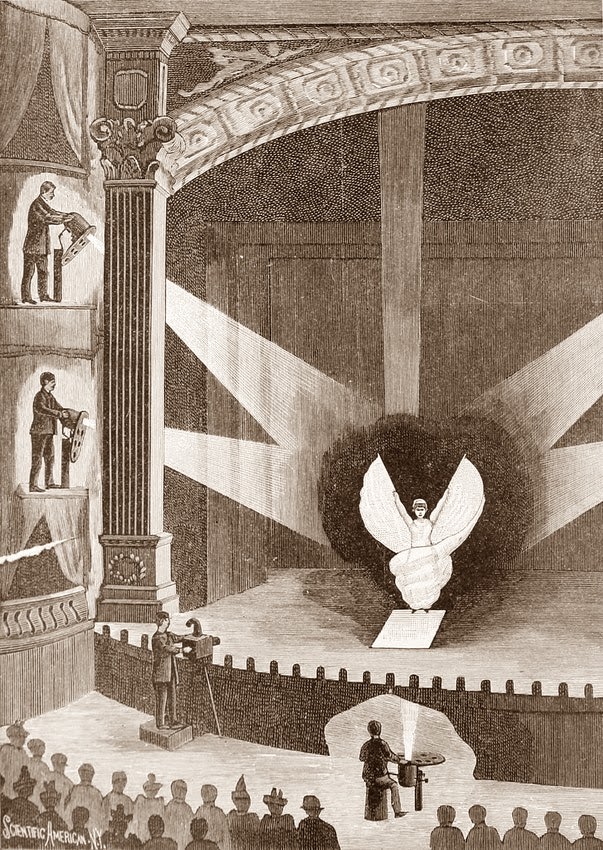

Fuller achieved her awesome artistic marvels through scientific innovation. The two images pictured below expose Fuller’s groundbreaking experiments in stage lighting. Van Looij painted Fuller, the apparition; the diagrams reveal the mechanics necessary to accomplish this metamorphosis.

Right: An unauthorized illustration originally-published in Scientific-American,1896

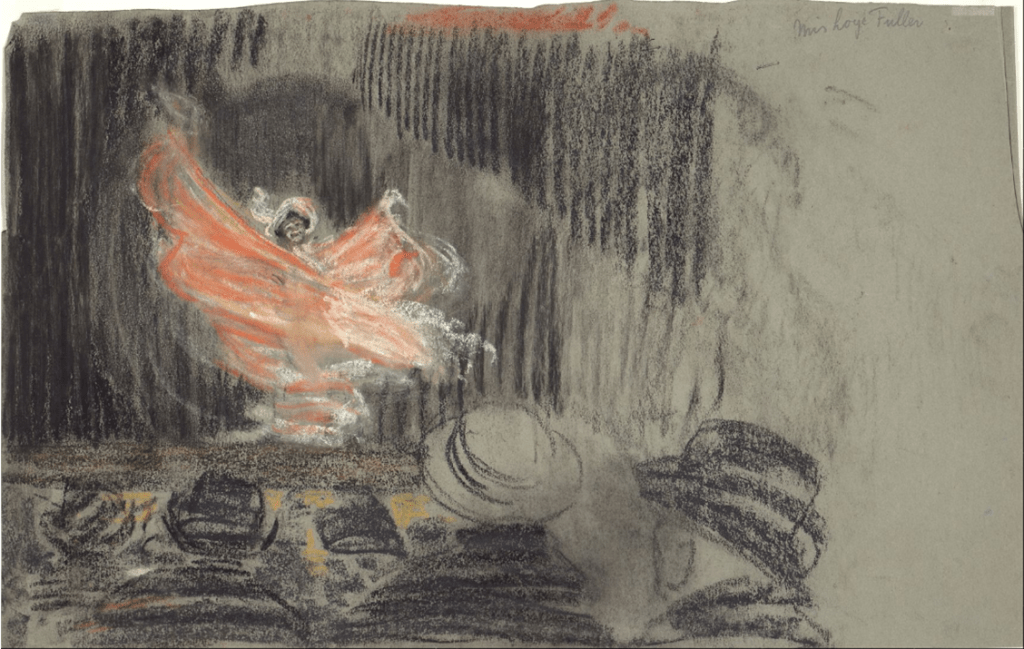

A second image, Dancer Loïe Fuller, also enticingly named Nightclub Dancer, by the photographer and lithographer, Bernard Eilers (1878-1951), presents Fuller dancing in a venue primarily occupied by male spectators. In the top right-hand corner, the name Mis Loije Fuller is distinguishable, leading me to wonder if the title Nightclub Dancer was designated by someone other than the artist himself. Fuller does not qualify as a mainstream nightclub dancer. Early in her career, La Loïe performed in the variety-halls. Fuller, then a fashionable skirt dancer, was portrayed in the early 1890s by the Flemish artist Théo van Rysselberghe (1862-1926) as a charming dancer in black stockings, holding her ankle length dress daintily outwards whilst gently inclining forward. The audience, to whom she bows, is not displayed. Moreover, Van Rysselberghe never suggests any of the specific innovative features that made Fuller’s performance so unprecedented; yards of undulating silk and dazzling light effects.

Bernard Eilers, on the contrary, seizes the moment, capturing the exhilarating flow of Fuller’s draperies in space. You can practically visualize the fabric sweeping upwards as Fuller thrusts the bamboo rods diagonally across her body; the hazy white streaks morph into flying orange ribbons. Equally stunning is the whirling sensation the artist creates as the wealth of silk wraps around the dancer’s lower legs. The British photographer, Samuel Joshua Beckett, preserved similar moments for prosperity in a series of striking outdoor photographs of La Loïe dancing, taken around 1900.

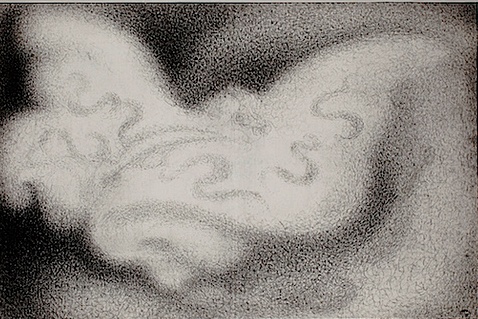

Fuller is known to have performed in Belgium a number of times. On one of these occasions, the artist Georges Lemmen (1865-1916) created a most unusual, though representational image of Loïe Fuller. Lemmen, at the time an impressionist with an avid interest in pointillism, composed an image where the veiled Fuller merges in unison with the stage lighting to evolve into a near abstract form. The image allows some sense of recognition; Fuller’s head can just be discerned and the rippling pattern on her airborne skirt most probably suggests that Lemmen’s witnessed the famous Serpentine Dance, but even so, the impression remains purely ethereal.

I mentioned that this artwork, though seemingly non-corporeal, is nevertheless representational. Contradictory as this may sound, the following photograph will clarify my point. Permit me first to explain that, except for three images, all the published photographs of Fuller were posed either in a studio or outdoors. The photograph, presented below, is a unique image taken during a live performance at the Thèâtre de l’Athénée in Paris in 1901 by an anonymous photographer. The image offers an authentic glimpse of the genuine Fuller as she contrives swirling spatial shapes that weave and glide on a stage overflowing with eloquent light. I must point out that during the actual performance, the stage would have been dark; the photographer needed to adjust his lighting to capture this thrilling moment.

The similarities between this photograph and Lemmen’s work require no explanation. Both works illustrate the otherworldly, mystifying Loïe Fuller. She, like no other before her, was dance, form, space, and light personified. No wonder that La Loïe enchanted realms of artists, making it all the more unfortunate that so few were of Dutch or Belgian origin.

* Two links for anyone interested in reading about the other dance paintings by Jacobus van Looij : The Magnificent Red Dancer and The Captivating Flamenco