Nymphs, muses, and putti are not the first figures that spring to mind when discussing art in The Low Countries. More likely our thoughts turn to peasant festivals, tavern scenes, landscapes, and portraits by celebrated artists like Bruegel the Elder, Rembrandt, Vermeer, Frans Hals, and Jan Steen. And yet, at a time when these and other old masters flourished, classically inspired artworks were also in great demand. A distinct audience, predominately aristocracy and members of high society, commissioned classical, allegorical and mythological works of art to embellish their palaces and rural mansions. Not infrequently, these ancient and Arcadian scenes featured graceful muses, dancing shepherds, hovering nymphs and echoing Renaissance Italian art, a generous sprinkling of endearing putti.

The Dutch painter, Maarten van Heemskerck (1498-1574), a contemporary of Pieter Bruegel the Elder, was one of the first Dutch artists to travel to Rome. He remained there from 1532 to 1536/7, studying ancient Roman architecture and sculptures and no doubt embracing classical literature and mythology. All his future work was touched by his sojourn in Italy. It is possible that van Heemskerck was acquainted with Baldassare Peruzzi’s work Apollo and the Muses (1514-1523) depicting the god Apollo performing a round dance together with his nine muses. Van Heemskerck’s version, painted between 1555 and 1560, illustrates Apollo and his muses at two separate, but interrelated, moments. In the foreground, Apollo, playing the lyre, reposes with four of his muses. The other muses gather round Euterpe, muse of music, song, and lyric poetry, who is playing fastidiously on a Renaissance table organ. A delightful extra is the scrutinizing glance of the imperturbable parrot. And tucked away behind the table is an impish, irritated, putto pumping the bellows. Moving up the hill, bypassing various symbolic emblems, a pan flute, a cithara, a lyre, and a tragic mask, Apollo leads the muses in a round dance. They move gracefully, with an ease reminiscent of the dancing figures in Andrea Mantegna’s Four Women Dancing (c. 1497) or Leonardo da Vinci’s Three figurative studies of dancers and study of a head (c.1515).

Where Maarten van Heemskerck returned to The Netherlands, inspiring a new generation of artists, the Antwerp-trained Pauwels Franck (c. 1540-1596) moved to Italy, eventually residing in Venice. He soon became known by his Italian name Paolo Fiammingo, and presumably worked as an assistant to Tintoretto. Later he opened a successful studio in Venice, receiving international commissions.

The Allegories of Love, considered Fiammingo’s masterpiece, is a set of four large panels now housed in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna. From a dance point of view, the panel Mutual Love/Reciproco amore presents an intriguing thread. The scene is idyllic; two instrumentalists are poised on the slope. The foreground is reserved for amorous pairs and playful putti. Farther back, in the centre of the painting, disrobed nymphs delight in a round dance. To all appearances, their dancing — hopping, cross-over steps, skipping — is rudimentary. Their hands are joined well below the waist, allowing the artist to highlight the subtle twist of the dancer’s shoulders as well as accentuate delicate gestures of the head. The tranquillity the dancers radiate, contrasts evocatively with the amorous sphere in the foreground.

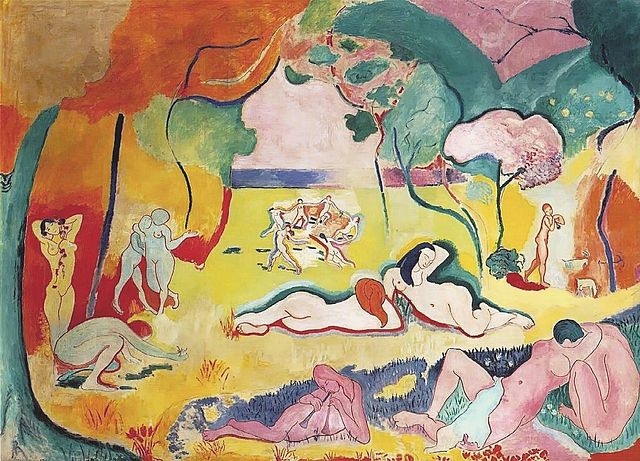

The Italian artist and draftsman Agostino Carracci (1557-1602) produced an engraving of Mutual Love somewhere between 1589 and 1595. Bearing in mind that prints and engravings were openly sold on the (art) market, it is possible that Fiammingo’s work, via Carracci’s accessible print, became decidedly popular and readily available. So memorable, in fact, that Matisse’s painting Le Bonheur de vivre arouses one’s curiosity. Could Matisse have been inspired by Carracci’s well-known print? There is absolutely no documentation to substantiate this thought, but when comparing the two works there is no denying that, composition wise, there is an uncanny similarity. In both works, the nudes adorn the side flanks, forming an open stage for the centre dancers. The portrayal of the round dance, however, is visibly different. The dancers in Carracci’s engraving are relatively serene, moving forward with a certain restraint. Matisse, on the contrary, presents exuberant dancers, moving deliriously, thrusting the circular shape onward as if in a frenzy. The movement and the body shapes of these dancers surely prefigure the ecstatic figures of La Danse.

Right: Henri Matisse – Le bonheur de vivre – 1905-06 – oil on canvas – 176.5 x 240.7 – Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia

The illustrious writer, historian, and painter, Karel van Mander painted numerous classically inspired artworks, but none that included a round dance. An anonymous artist, within his circle, deserves that credit. The artwork, a grisaille, descriptively named Dancing under trees in a Landscape, draws the dancers vividly into the foreground. A poetic landscape, enriched with a stone vaulted bridge and castle ruins, acts as decor. Not unlike the above paintings, the front section — the musicians and two carefully positioned draperies — forms a semi-circle creating a podium for the dancers. In the ‘wings’, two indecorous satyrs peep inquisitively from behind the tree. No doubt, the voluptuous movements of the dancers aroused their interest. But why are the dancers alternatively dressed and disrobed? And why are some dancers facing outwards and others inwards? Has the artist chosen these particular poses to exhibit their enticing physique? A number of the dancers have a silky, marble-like skin texture, evoking suggestive classical sculptures. The sensuality of the nude dancers is unblushingly accented; the hips, torso, and pelvis being thrust out of natural alignment. And finally, a round dance by its very nature, is communicative and unifying. For the most part, these dancers are introverted, glazing downwards as if disregarding their partner. All in all an enigmatic work.

Muses, nymphs, and maenads, dancing or otherwise, were much-loved figures in the art of The Low Countries. In fact, many artists of The Northern and Southern Netherlands specialized in mythological works. The three paintings, below, form a small selection of the numerous classical dancing figures painted by Flemish and Dutch painters. The very successful Flemish artist Erasmus Quellinis (1607-1678), a pupil of Rubens, was known for his history paintings, portraits and allegorical works. The nymphs portrayed in Nymphs dancing around a tree are arresting. Quellinis has positioned them directly in the foreground; they occupy the greater part of the canvas. Their apparently lively dance — the bare-foot dancers give the impression of hopping or skipping freely — is staged under a tree laden with a bouquet of colourful flowers. It amazes me why these nymphs, dancing effortlessly and candidly in the open air, should look so forlorn. A 1787 copy, an engraving by the French artist Charles-Etienne Gaucher, shows, in reverse, an identical scene but with somewhat cheerier nymphs.

The centre painting, an Arcadian landscape, shows Diana, goddess of the hunt, resting. On the elevated clearing, four of her nymphs have formed a circle. One of the nymphs seems distracted. Could this distraction be caused by that strange tree-like figure lingering in the background? The artist, Dirck van der Lisse (1607 – 1669), was not only a well-known painter and receiver of royal commissions, but he also served as mayor of The Hague on several occasions.

Frans Francken II, son of the acclaimed artist, Frans Francken the Elder, was a prolific artist known for his religious, historical, mythological and allegorical paintings. The slender muses in his painting,’The Muses Dancing in a Wooded Landscape’, perform a refined circle dance under a lantern-like decoration dangling on thin string suspended between two trees. The sextet, dressed in flimsy, flowing gowns, are all portrayed with one leg gently raised. This delicate pose together with the subtle positioning of the dancer’s head, the nuanced rotation of the torso and Francken’s light paint strokes create an ethereal quality.

Centre: Dirck van der Lisse – Diana and her nymphs dancing in a wooded landscape after the hunt – 1634 – 72.5 x 90.5cm – RKD

Right: Frans Francken II – The Muses Dancing in a Wooded Landscape – 28.6 x 24.5 – Mutual Art – RKD

His name may not ring a bell, but no one who has seen the painting ‘Fishing for Souls‘, in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam can forget the overpowering impact of Adriaen Pietersz. van de Venne’s satirical allegory representing Protestants and Catholics literally fishing for souls. The versatile Dutch artist, Van de Venne (c.1589-1662), painter, book illustrator, poet, and publisher can be credited with many dance works. At a later date I will discuss his work more fully, but for the purposes of this post I will limit myself to two circle dances; dancing putti and dancing nymphs. The works An Allegory of Spring with putti dancing and Nymphs dancing, painted en brunaille, are comparable; a tree or trees occupying the left side, hovering putti in the sky and figures dancing near the front of the panel. The putti, as one has come to expect from these mythological beings, are plump and playful, dancing in a lively, frolicsome fashion. The dancing nymphs, however, may temper our expectations; they are a little chubby and not very refined. They are simply jolly dancers, enjoying themselves thoroughly as the musicians, two shadowy figures in the left corner, play an energetic tune.

Left: An Allegory of Spring with putti dancing – c. 1650 – Sotheby’s

Right: Nymphs dancing – 1651 – 58.5 x 74 cm – oil on panel – ARTCURIAL

The artist and art theorist Gerard de Lairesse (1641-1711) requires no introduction. Nicknamed the ‘Dutch Poussin’, de Lairesse specialized in allegorical, historical and mythological subjects. He was one of the most acclaimed artists of the second half of the 17th century, receiving commissions from royalty, the government and wealthy merchants. He devoted himself exclusively to what he considered the loftiest form of art, classical subjects. Danse d’enfants, with the dancing toddlers or putti, is an allegory illustrating the sense of hearing, one of the five senses. These putti cannot resist dancing to the melodious chimes that the goddess plays on the triangle. Each chubby figure has a compelling expression. My favourite is the overly smiling figure, prettified with a pearl necklace, who looks directly at the viewer.

Danse d’enfants – oil on canvas – 58cm x 76.5cm – 1668 – Musée des Ursulines de Mâcon

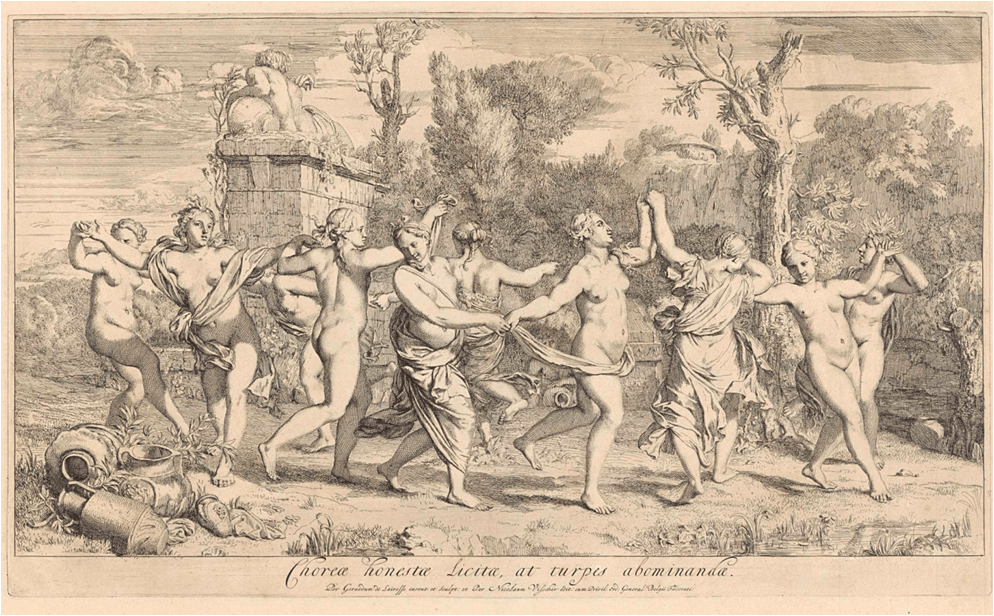

Dancing Nymphs – etching – 348mm x 587mm – 1685 – Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Dancing Nymphs, an etching on paper, presents full-figured nymphs dancing spontaneously in the open-air. On the stone wall, just behind them, there is a statue of a recumbent river god. Presumably, the nymphs gathered to collect water; various pitchers and jugs lay on the ground. In a small clearance, this group of nymphs, both clothed and unclothed, dance barefoot in a circular chain. Their dance vocabulary is mundane; walking, a simple cross-over step and occasionally a slight lift of the lower leg. De Lairesse, in contrast, emphasizes the rotation, the twist and the curves of the upper body, alternately displaying the front and back views of the nymphs.

The inscription under the illustration is intriguing. The Latin text informs the viewer that, ‘Honorable dances are permitted but profane dances are abominable’. This, of course, is a matter of opinion, but how this relates to de Lairesse’s medley of nymphs is perplexing. Perhaps Jan Steen’s coarse dancing peasants come to mind. Be that as it may, classicism flourished in 16th and 17th centuries Dutch and Flemish art. And dancing nymphs, muses and putti were frequent participants.