The circle dance, the most ancient of all dances, embodies varying emotions and qualities. There are, amongst other forms, folk dances, community dances, rituals, sacred dances, medicine dances, and religious dances. All these dances have a different character and distinctive purpose. Artists of The Low Countries regularly included images of peasants joyfully dancing a circle dance. Some artists also ventured in a different direction, painting frolicking cats, rats, monkeys, and other less appealing creatures who, in their own unique fashion, executed the eternal circular dance.

To start with, a rather curious painting, very Boschian in content, but without the great artist’s overpoweringly daunting premonitions. The perplexing scene unfolds in a grotto setting, near the sea shore. The canvas is filled with weird human figures, hybrids, flying fish, witches, and partially recognizable animals. The viewer is instantly drawn to the immense cauldron from which a hazy substance evaporates. Grotesque creatures inhabit the vapour. It is impossible to miss the atrocities taking place in and around the scorching vessel. Then, as if there were no witches, no monstrosities, no misplaced skulls or bones, eight ‘charming’ cats, having joined their front paws, and elevated themselves onto their back paws, dance in a jolly ring.

This talented group of felines practically upstages the inexplicable, sinister goings-on. As common in a round dance, these tabbies face inwards, practising sideways and cross-over steps. And there is music! A 16th century ginger cat is seated comfortably on a stool playing a woodwind instrument. The anonymous artist also included another enchanting cat. This proud and inquisitive animal appears amazed to see his colleagues dancing. On the other hand, for all we know, he merely wishes to join his peers. As amusing as these adorable cats are, they foreshadow another, less obvious circle dance. In the distance, high on a cliff, there is a second circle dance. The figures, though indistinct, reveal women dancing along side with bizarre figures accompanied by a devilish trumpet player.

Left – the cat dance – detail

Right – dance on the cliff – detail

The Witches’ Cove is a work by a follower of Jan Mandijn (1500 -1560), who in turn was himself a follower of Hieronymus Bosch. Mandijn was born in Haarlem, a city near Amsterdam, travelling to Antwerp in 1530. His style, though similar to Bosch, is somewhat looser, colourful and tends towards the whimsical. His work, Temptation of Saint Anthony in a Panoramic Landscape, is laden with hybrids, reptiles, insects, and flying creatures, all within a world landscape setting. Saint Anthony, the Golden Legend recounts, was tormented by demons. Mandijn surrounds the faithful Anthony with a motley array of demons and hybrids, each one a possible contender for a Bosch canvas.

In the foreground, slightly in front of the awkward demons, Mandijn plants a gigantic egg shell. One by one, eerie insects and curious creepy-crawlies leave their shelter to form a circle; each creature clinging onto their neighbour’s extremity. This surreal circle of vermin performs a diabolical dance to the strangest musical accompaniment conceivable. Those quirky demons that tower over the ‘odd dancers’ each have a musical instrument. A close look reveals a drum, a harp, a flute, bagpipes, and a petite girlish demon playing a triangle.

The harp, the lute and a flute-like instrument also make an appearance in The Last Judgement, a forbidding canvas by Hieronymous Bosch. In the central panel, just above a lantern-come-brothel, a group of seven nude figures dance around a mighty musical instrument that boasts no instrumentalist. The dancers, reminiscent of figures encircling a classical amphora, revolve around the upper ridge of a plateau next to a nude figure ensnared within a harp, who is mercilessly suspended as a ghastly creature approaches. This circle dance is a hideous form of a carole. The dancer’s movements are stylistically primitive, coarse, and rudimentary. Bosch, an artist of the late Middle-Ages, considered dance and music to be partners in lust, lewdness, and impropriety punishable by extreme banality and barbarity.

David Ryckaert III, a well-respected artist, whose aristocratic patron Archduke Leopold Wilhelm owned several of his paintings, created a most gruesome, nightmarish circle dance. Among his more traditional genre pieces, Ryckaert occasionally wandered into the realms of witchcraft and alchemy. The Dance of the Leprechauns, also known, among other titles, as The Monster’s Dance, features five partially morphed figures — witches? humans? devils? — revolving in a ghastly ring dance. This horrendous ritual ensues in a semi-lit cave; a fiendish fire blazes in the distance. There are at least two onlookers; an ogling figure, resting between the rocks, and a second figure, a mysterious mortal, perching on the lofty ridge. And that foul creature reposing on the ground is the accompanist, playing some type of flute.

Despite the distasteful narrative, Ryckaert’s vivacious, potent representation of movement is striking. The figures are contorted; they twist, flex, and bend into various trajectories. They cringe in anguish. The unorthodox circle moves dynamically; the chicken-like paws trampling gracelessly step after gawky step. Ryckaert’s sense of motion is utterly persuasive.

Perhaps no less a disagreeable subject, but unquestionably more appealing is The Dance of the Rats, attributed to Ferdinand van Kessel (1648-1696), a Flemish baroque painter known for his landscape, still-life and genre paintings. This small work was originally part of a larger canvas. Only the cut-out of the dancing rats survives. Are they not the most endearing group of venom imitating human behaviour? Not without a certain degree of gallantry, they have risen onto their rear paws and presented their wrists to their partners in preparation for a ‘refined’ social dance. The quartet stands quite still; only their heads and focus provide any indication of movement.

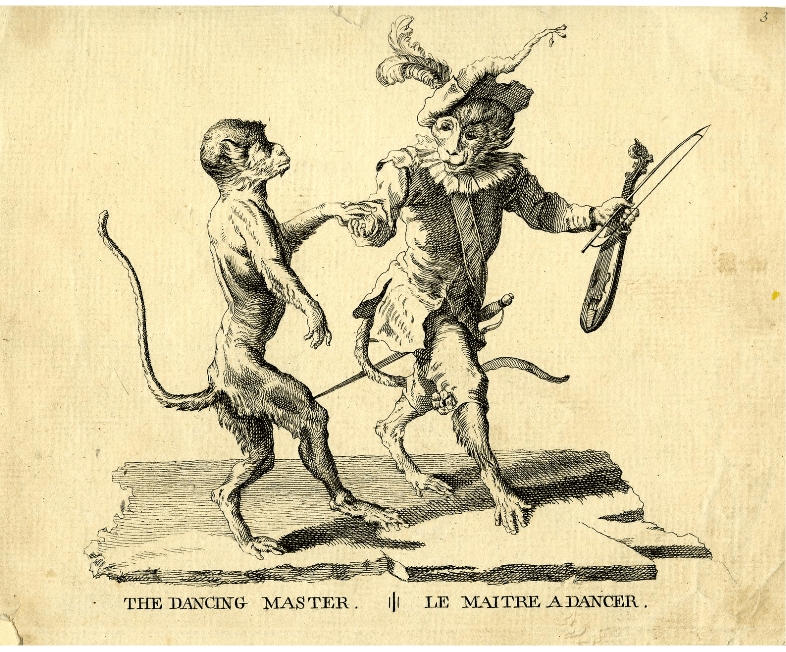

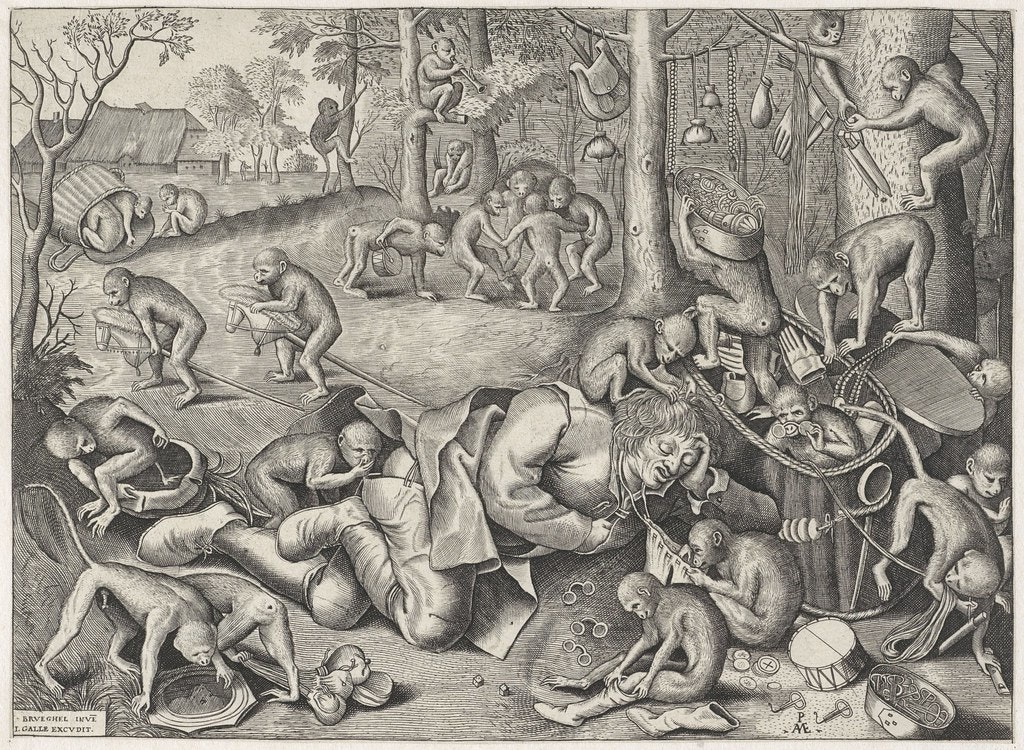

Of all the animals depicted in Flemish art, the monkey was by far the most popular. Monkey images appeared in every plausible setting and situation; in great halls, in barber shops, enjoying a game of cards, playing musical instruments, and dancing. The monkeys imitated human behaviour, behaving and dressing as humans in realistic situations. The images, however amusing, were intended as satire, highlighting the frivolity and folly of human actions. Monkeys and monkey antics had, of course, adorned illuminated manuscripts for centuries, but it was Pieter Breugel the Elder and Peter van der Borcht who introduced singerie as a specific art genre.

The image, The Sleeping Pedlar Robbed by Monkeys, designed by Bruegel the Elder and engraved by Pieter van der Heyden, illustrates a traditional folk tale; monkeys that pilfer an unsuspecting pedlar. Many of the monkeys are thoroughly devious. Four more rhythmical simians, by contrast, amuse themselves dancing in a small circle. Their movements are earthbound, rudimentary, just like their primitive bearing. As they trudge heavily from one foot to the other, one wonders if they are echoing the beat of the drummer monkey or heeding the flute playing monkey lodged on a tree branch?

But even though the plundering monkeys occupy themselves with unorthodox activities, they are intrinsically monkeys fooling about. This cannot be said about Pieter van der Borcht’s Round Dance with Monkeys. These anthropomorphic monkeys are participating in a village feast. They are dressed meticulously. The ‘ladies’ are attired with frilled blouses, adorned with a dainty row of buttons and stylish swinging skirts. Many of the male monkeys wear a well-tailored jacket together with a carefully chosen hat or cap. There are musicians, children, lovers and, possibly, as a reminder of the true nature of the monkey, one or two non-anthropomorphic monkeys.

How these monkeys dance! They are light footed, energetic and nimble. The front couples hop, turn, twist, and revolve in movements and shapes surely reminiscent of Bruegel and his peers. At the top of the hill, there is a line dance with monkey dancers forming an arch to pass under. And as pertains to any peasant festivity, the bagpiper is present. The circle dance takes place in the centre of the engraving. Male and female monkeys alternate, holding onto each other’s wrists. The monkey’s movement, expression, dress, and carriage are virtually interchangeable with the numerous renditions of dancers in a Flemish village kermesse painting. Just one difference; the monkey playing the bagpipe is seated on a tree bough and not, as in a Flemish village scene, standing near a tree.

Pieter van der Borcht (1545 – 1608) – Round Dance with Monkeys – etching – publisher Philip Galle – 289 mm x 207 mm – Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

The genre singerie remained highly popular throughout the 16th and 17th centuries. It was not usual to see anthropomorphic monkeys in familiar village scenes or genre paintings. Ferdinand van Kessel, known from The Dance of the Rats, painted a colourful work, Singerie, Village fete and dance in front of an inn, which virtually contains the same elements present in a more traditional village scene. Van Kessel’s painting recalls the work of Pieter Brueghel the Younger; the monkeys imitate village folk drinking, dancing and feasting. Van Kessel, just as in many Flemish village scenes, has a rustic (monkey) indiscriminately urinating against the tavern wall. And to complete the convivial scene, van Kessel places an obliging dancing dog in the lower right-hand corner.

Besides Ferdinand van Kessel other Flemish artists like Frans Francken the Younger, Abraham Teniers, David Teniers the Younger and Sebastiaen Vrancx were all renowned for their entertaining anthropomorphic works. Singerie became a rage, travelling throughout Europe, and most especially to France; Christopher Huet, a French artist, becoming an illustrious exponent. Singerie retained its popularity well into the 18th century. The anthropomorphic circle dance, on the contrary, was gradually succeeded by the more trendsetting dance forms. A new epoch presented itself; the monkey was instructed in the elegant art of the minuet.