Circle dances have existed since the dawn of civilization; they belong to all ages and all nationalities. Artists, from the earliest times, have depicted the circle dances in sculpture, murals, illuminated manuscripts, and paintings. This post will focus on images of circle dances, as danced in villages, by Netherlandish artists of the 16th and early 17th centuries.

The circular village dance is a community dance. Anyone can join in; men, women and children. Age makes no difference. No specific training is required; the participants learn the dance as they go. The steps and movements are straightforward. All the dancers face inwards and are connected to each other by either holding hands, or placing their hands on their neighbour’s shoulders or waist. The circular formation essentially unifies the merrymakers, as if festive energy flows from one person to the next.

One of the earliest images of a circular village dance is by Pieter Aertsen (1508-1575), an artist famous for his genre paintings, incorporating a biblical scene. Even before Bruegel the Elder, Aertsen painted the peasant as a monumental figure. In his well-known work, The Egg Dance (1552), peasants command the foreground. An earlier painting, Village Feast with dancing peasants (circa 1535), attributed to Pieter Aertsen, has neither monumental figures nor a religious vista. Instead, this colourful image presents a scene showing peasants dancing in a village square. As customary at the time, the viewer has a high vantage point. The dancers are surrounded by trees, a church and, as one would expect in a village scene, the all-important tavern, named, as the red banner indicates, The Swan. On the same level, we are granted a little down-to-earth humour. A young man, an admirer perhaps, has climbed onto an awning only to be surprised by a woman emptying a chamber pot directly above his head.

The dancers, rather slender, twiggy figures, partake in a circle dance. Their circular formation is traditional; the men and women stand alternatively, clasping each other’s hands. All the figures appear somewhat static. Some of the men have raised one leg, but this action does little to incite any animation. Contrary to the clarity of Aertsen’s later work, these figures are not all distinct, even blurred at times. Various figures appear to speak to each other, others gaze into space, but for the most part, their facial features are unremarkable. The most outstanding figure is the dancing woman in the foreground. Poised practically in the centre of the painting, she rotates her torso to face the onlooker. Is she inviting us to join in? Did someone call her? Or perhaps she suddenly notices the basket that contains a playful dog is about to tumble over.

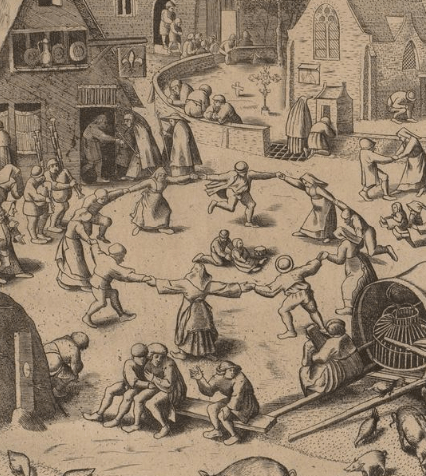

In The Dance*, a book compiled by the eminent English musician and collector of English folk song and dance, Cecil Sharp (1859-1924), I discovered a charming drawing by an anonymous Netherlandish artist created, according to information from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in the 1520s. The work, A Country Dance, is a relatively small pen drawing (18.9 x 28.6 cm), supplemented with brown and black ink. This very early work presents a refined company dancing a round dance, possibly a carole, in the open air. Just behind the dancers, in the centre of the image, the artist has drawn a detailed sketch of a building with a stepped gable; a typical example of Netherlandish architecture, as are the farm house and the windmill.

A Country Dance presents a gathering of elegantly dressed ladies and gentlemen participating in a traditional round dance. The dancers, alternatively spaced and holding hands, acknowledge each other and some even enjoy a private chat with their adjoining dancer. The ensemble’s stately posture and gracious demeanour would suggest that the dance is executed at a leisurely tempo. This presents the opportunity of clearly observing the unique personality of each figure. All the facial gestures, including those of the musicians and jester, are distinctive and expressive. The illustration below is an enlarged excerpt showing the facial expressions of the jester and musicians in more detail. All the characters are thoroughly amusing, but none can compete with the instrumentalist who plays the tabor; his droll expression is simply hilarious.

A Rural Feast painted by the artist, art historian and art theoretician Karel van Mander (1548-1606) presents a very different story. There is no shred of refinement in the foreground. Coarse characters in the throes of lustful behaviour, insobriety, gluttony, ribaldry, greed and sloth are the centre of attention. Equally prominent is the child answering nature’s call to the pleasure of two unquenchable pigs.

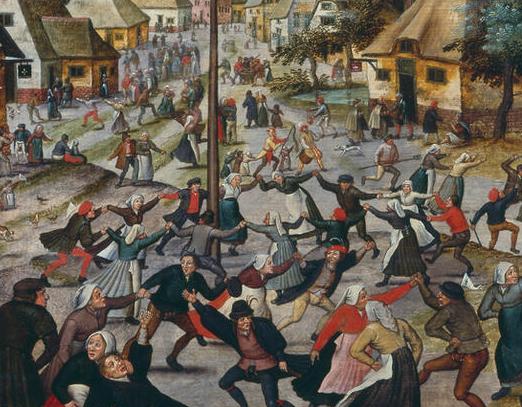

The circle dance takes place in the middle; the boisterous peasants revolve swiftly around what appears to be a tree without branches or a meandering maypole. The dancers move briskly, prancing and capering to the bagpiper’s cheerful tune. Van Mander’s narrative becomes graphic as the viewer proceeds towards the background. There, devout peasants are shown walking to church; they resist the unrighteous, happy-go-lucky merriment so glaringly exposed in the foreground.

This painting, now in the Hermitage, formerly belonged to Pyotr Semyonov (1827-1914) the great Russian geographer and statistician. Semyonov, a wealthy intellectual, and member of a noble family, collected Old Dutch Masters. I could not help wondering why an affluent man would wish to acquire such a bawdy painting. Where would a gentleman of his status display such a painting? This certainly is not a work that could have a place of honour in a dignified aristocratic dining room. I can, however, imagine the painting adorning the wall of a gentleman’s smoking room. Feasibly, A Rural Feast offers the opportunity for discussion; most likely, with a glass of wine in hand, mocking the peasant way of life.

It would not be an exaggeration to say that circle dances invariably surface in village fair paintings, for the most part, as one of the various activities taking place in the narrative. There are two basic forms of circle dancing; either a simple round dance or a dance around a tree or maypole. Pieter Bruegel the Elders’ well-known print, The Kermis at Hoboken, highlights a spirited circle dance of peasants dancing around two seated children. There is also a circle dance, be it modest with only a few dancers, in the background of the famous painting The Fight between Carnival and Lent. Pieter Balten, Hans Bol, Gillis Mosaert, Jacob Grimmer, Marten van Valckenborch, Pieter de Bloot, Jacob Savery, Lucas van Valckenborch, Jan Steen, among many more artists of The Low Countries, all include circle dances in their work. And then there is Pieter Brueghel the Younger, unquestionably the most fashionable artist of peasant images, who not only made some delightful paintings of circle dances but at times elevated the round dance to the principal theme.

The tondo, Peasants dancing around a tree in a village street, is barely 16.5 centimetres in diameter. Although the background is full of activity — men fighting with swords, a couple hugging, a drunken man being escorted home — the dance around the tree immediately attracts attention. The dancers are rowdy, swaying, bending, rocking and whatever else, so enthusiastically that their hands become disconnected. Bruegel portrays the dancers in a haphazard fashion, with only the bagpiper and flutist to link the chain.

Brueghel’s 1634 work, Village scene with dance around a maypole, is an invitation to dance. Brueghel places the dancers, who incidentally look amazingly similar to those in the tondo, on an elevated plateau. The village square, filled with peasants performing a multitude of activities, is situated at a marginally lower level. The entire foreground, with the exception of a few spooning couples and a couple running up the mound is devoted to the dance. A lively couple dance effortlessly not far from the picnicking lovebirds, and other rustics improvise a brusque dance around the tall village oak. The maypole dancers, once again a circle of alternating men and women, are by no means disciplined. Inspired by the bagpiper’s spirited rhythm, they pull and tug in opposing directions, keenly jumping, hopping and flinging together any and all movements. The result, a lopsided circle dance, wholeheartedly enjoyed by all the carefree participants.

Worth mentioning are the three paper crowns that hang high in the tree. These are similar to the crowns worn by a bride on her wedding day. In village tradition, prospective brides were the first to dance around the maypole; an ancient symbol of fertility, of rejuvenation.

Brueghel the Younger painted three different versions of a circle dance, the above two focusing primarily on the dance and the 1620/30 version where the dance around the maypole is contained within a bustling village feast. St. George’s Kermis with the Dance around the Maypole, of which there are fourteen extant versions, has all the characteristics of a world landscape: an elevated vantage point, a distant mountain setting, a meandering river, and a panoramic landscape consisting of houses, churches and faraway castles.

The foreground is filled with dancing, drinking, urinating and relaxing peasants. There is even a bagpipe player desperately trying to outplay the pandemonium. As in the previous paintings, Brueghel placed the dance around the maypole on an elevated mound. In the village beyond, at the foot of the mound, there is a jester, playing children, men fighting, a man pushing ‘his woman’ with a pitchfork, and dancing peasants, to name but a small selection of the activities.

The movements that the dancers execute are reminiscent of Brueghel the Elder’s dance figures. Brueghel the Younger dancers, all small figures, have none of the idiosyncratic personality of his father’s iconic dancers. Brueghel the Younger emphasizes the festive scene and not the unique character. In the immediate foreground, various couples dance a lively springing dance. Behind them another four peasants hasten themselves in a frolicking chain dance. And behind all this excitement, peasants dance passionately around a maypole that barely fits within the frame. Once again, parallels can be drawn between father and son. The swiftness of motion, the pulling action, the slant of the body, the arm distance and the leg movements must surely have been inspired by Bruegel the Elder’s print Fair at Hoboken.

Pieter Brueghel the Younger – The Dance around the Maypole – Musées d’art et d’histoire, Genève – detail

Pieter Brueghel the Younger, an incredibly prolific artist, contributed to the popularization of the peasant genre. He and his contemporaries included circle dances in the majority of their festival paintings. The circle dance remained a favourite theme during the 17th century. First, as shown in this post, in village festivals and later, when tavern themes became stylish, moving into or around the drinking establishment.

* THE DANCE An historical survey of dancing in Europe – Cecil J. Sharp and A.P. Oppé – f.p 1924, republished 1972 – plate 18