Pieter Bruegel the Elder was by no means the first Netherlandish artist to paint peasants or peasant festivals, but he is unquestionably the most renowned. Bruegel’s earliest images of peasant festivals, like the slightly earlier Pieter van der Borcht, present the viewer a bird’s eye perspective of an entire village square where rustic folk are exuberantly celebrating a holy day. The viewer, as in Kermesse at Hoboken, is invited to explore a potpourri of activities. The tavern is the most prominent establishment in the foreground; peasants enjoy themselves drinking, dancing and generally revelling. The front layer is filled with children playing, archers practicing, the village fool, animals, often pigs, roaming around and a myriad of diverse activities. Take, for example, the man who immodestly places his hand under the woman’s skirt. This, partially concealed by the wagon bonnet, takes place at the very front of the image. Farther to the back, a makeshift stage accommodates entertainers or possibly a charlatan selling his wares. With all this effervescent activity going on, you could easily forget that this feast celebrates a saint’s day, a religious holy day. The church and the religious procession, though designated more to the background, is, nevertheless, a well-defined reminder of the sacred significance of the holy day.

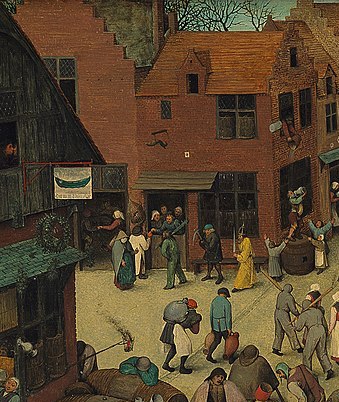

Although the following painting, The Fight Between Carnival and Lent, (1559) contains but two dancing moments, it gives a good impression of how Bruegel depicted a peasant festival in his earlier work. As customary, in the world landscape style, the horizon is high, presenting a panorama view. The viewer, as if standing on a hilltop, can see the entire village square and beyond in one scenic view. The busy village scene is framed, similar to Kermesse at Hoboken and The Fair of Saint George’s Day, by various buildings; the church and the tavern are always prominent. A multitude of characters, more than two hundred I am told, are partaking in this religious feast. There is an immense diversity amongst the villagers; some wear festive costumes, others are dressed in religious robes. And not to be missed, there is a jester in a typical mi-parti outfit, practically in the centre of the painting. Regardless of occupation, station, or age, all the figures are tiny. Every section of the painting tells a unique story; there is, for example, a woman baking waffles, a group of cripples maneuvering across the square, a woman spring cleaning, actors performing the play The Dirty Bride, and figures dressed as if they have escaped from a Bosch canvas. All the figures are equally essential and noteworthy, with the exception of the two pivotal allegorical figures, Carnival and Lent. They upstage all the other characters, performing a mock joust seated, not on a horse, but on a type of push-cart. Carnival and Lent not only dominate the foreground, but physically divide the painting into two halves.

To the left of the bulky Carnival figure, who just happens to be sitting on a wine barrel, stands the local tavern. Shrovetide, the feast depicted, was celebrated with excessive drinking. One besotted fellow is slumped over a wine barrel, and another, a bagpiper in the upper floor window, is in the act of vomiting. And that drinking can lead to unexpected complications is the theme of the comic folk play, The Wedding of Mospus and Nisa (The Dirty Bride), that is presented in front of the tavern. Having had far too much to drink, Mopsus marries, to his own consternation, Nisa, a tattered, unkempt lass. We see the ill-suited newlyweds dancing in front of their shabby nuptial tent, accompanied by a musician playing on an improvised instrument. Moving farther back, a procession of lepers comes into view, a character dressed as a wild man enacts a play, a group of men and women perform a circle dance and behind them villagers enjoy a bustling bonfire. All this fun, drinking, lovemaking, and theatricals is juxtaposed against the right side of the painting, presided over by the old hag Lent. She, like her entourage, has an ash cross of Ash Wednesday on her forehead. Poverty, hardship, ailments and restraint are highlighted. The imposing church, adorned with a rose window, dominates the scene where a woman sells votive offerings, whilst the wealthy offer alms to the poor and needy.

Left: detail of The Wedding of Mospus and Nisa & Right: detail of ‘Wild Man’ street performance

It is not my intention to explicate the symbolism or the comprehensive content of this magnificent multi-layered painting. Rather, to indicate how Bruegel the Elder and his contemporaries, Hans Bol, Marten van Cleve, Pieter Balten and other 16th century Flemish artists composed the then fashionable genre, the peasant festival. Common to all artists is the panoramic view, the high horizon, the numerous small figures busy with a multitude of diverse activities, often framed within a market square lined with houses where a prominent church was never excluded. Pieter Bruegel the Elder, in the last years of his life, broke with this traditional panoramic view to create The Peasant Dance; the peasant triumphs in the foreground.

What a vibrant village square! The locals are celebrating a holy day, a feast dedicated to Saint George. Peasants drink, eat, dance and make merry. The merrymaking can be distinguished into two sections. The tavern scene, including the table teeming with coarse patrons, extends over the left half. The facial features of the kissing couple, the old woman, the arguing men and most especially the intoxicated man sitting next to the bagpipe player are so expressive, so close at hand that the viewer can practically participate in the festivities. The two endearing children, dancing a simple dance next to the musician, form a marked contrast to these rugged individuals. The girls must be very young, considering that even the older lass is short enough to fit under the tabletop. In the doorway, situated under the red flag, there is another couple whose movements echo the girl’s dance formation. They obviously have alternative objectives. The right side bursts with energy; the village dance is about to begin. The opening dance of a country fair, according to information provided by the Kunsthistorische Museum, traditionally began with a leaping dance performed by two couples only. That is the exact moment Bruegel has painted; you can see the two vivacious couples hopping and bouncing just behind, though partially concealed, the monumental figures. These two stupendous figures stride in enthusiastically, bypassing a tree adorned with a simple wooden frame displaying a woodcut of the Virgin Mary caressing her child. They, together with the right dancing couple, guide the onlooker, via a path of clasped hands, to the village church; a church, which on this holy day appears to be altogether neglected. In fact, all the figures have their backs turned to the church.

Bruegel’s composition of The Peasant Dance was unconventional. The traditional bird’s eye perspective is transformed to an eye level view. The viewer stands face to face with the revelling peasants. The bloated bagpiper and his jolly friend are eye-catching, but the large peasant couple, striding into the village square, stand out decidedly. They not only occupy a very significant section of the right side of the canvas, but totally uncommon for peasant paintings of the time, are shown from the back. They obstruct the view of the village square. Unlike The Wedding Dance (1566) where each of the main figures and their movements can be readily distinguished, these dancing couples are partially overlapped by this broad-shouldered crude man clad in an oversized black jacket. Where in the ‘traditional’ peasant festival setting, the viewer is granted an overall view, the viewer must now crisscross between the various figures. Each of the dancing couples usher the viewer to delve deeper into the painting. Note how the right couple is positioned exactly between the torsos of the sturdy running couple, whose clasped hands form a low ‘v’ shape. This counterbalances the high ‘v’ positioning of the right couple, drawing the viewer’s attention straight to the church. Additionally, the large peasant’s dynamic, forward thrust creates a second passageway. Progressing through the trapezium-like shape formed by the dancer’s arms and legs, the viewer is coaxed towards the smiling fool and a rather grumpy looking townsman.

Why is the townsman so discontented? What displeases him? This is after all a day of celebration. The dancers, the fool, the children, and the tavern guests all appear to be enjoying themselves. Even the coarse rustic and his woman are eager to join in with the festivities, though, if his ardent glance is any indication, he seems more interested in the tavern activities.

The Peasant Dance, a festive and apparently carefree painting, is not free from symbolism or social criticism. This, not to forget, is a time when church and state considered the peasant way of life to be boorish and crude. Dancing incited immorality. Dancing was frowned upon, except, according to Martin Luther, when done within the bounds of decency and moderation. Bruegel, though known to have a more charitable attitude than some of his contemporaries, nevertheless, confronts his viewer with moral undertones. The painting abounds in clues, revealing that there is more than meets the eye. Gluttony, anger, lust, and vanity, four of the Seven Deadly Sins, are all depicted in the foreground. The drunken man seated next to the bagpiper has a peacock feather in his cap; the symbol of vanity. The man in the black jacket heedlessly tramples over two strains of grain lying on the ground; Bruegel has arranged them in the shape of a Latin cross. His lady friend runs past a broken handle; a clear sign of her immodest character. And just above her head, a perfectly shaped jug, a symbol of virtue, hangs on the oak precisely under the woodcut of the Virgin Mary. Both totally ignore the dedication. The church, so prominent on the horizon, is deserted. Instead of spending the day in spiritual contemplation, the villagers turn their backs to the church. No doubt this prompts the irritable townsman and, I dare say, Pieter Bruegel to recall Luther’s argument to abolish all festivals ‘since the feast days are abused by drinking, gambling, loafing and all manners of sin, we anger God more on holidays than we do on other days’. *

* Marten Luther: letter to the The Christian Nobility of the German Nation – 1520 – source: T.M. Richardson: Pieter Bruegel the Elder: Art Discourse in the Sixteenth-Century Netherlands p.124