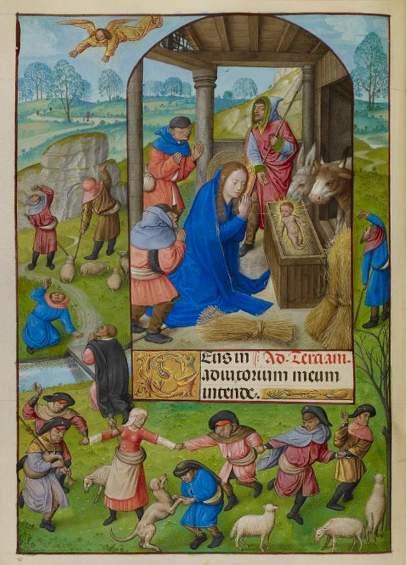

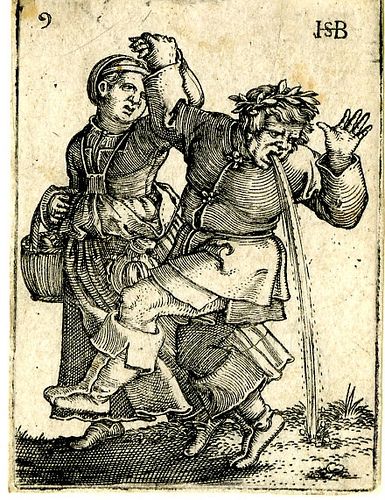

Images of peasants, dancing or otherwise, gradually evolved from marginal figures decorating illuminated manuscripts to the monumental figures that highlight Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s The Peasant Dance. Early peasant images, most especially by the German artists Sebald Beham, Barthel Beham, and Erhard Schön, invariably presented the rustic as foolish, grotesque, uncouth, and hideous. Art patrons amused themselves, relishing the more unsavoury aspects of the peasant way of life; in fact, images of drunken, vomiting, urinating, or defecating peasants were immensely popular. These hilarious features aimed to ridicule the hardworking, fun-loving peasant. Hieronymus Bosch (c.1450 – 1516) adopted another approach; on the outer panels of the triptych Haywain, (1512-1515), two peasants appear to be enjoying themselves in a frolicking dance. They, in comparison to the wayfarer, are small and seemingly trivial figures. Bosch, however, never uses dance as mere decoration nor does he ever use dance images as innocent amusement. To dance was lascivious. This peasant couple are sinners, symbolizing eroticism and depravity. The gallows on top of the hill serve as a harrowing reminder of their fate.

Sebald Beham – Dancing Peasants c. 1537 ( one example from a collection of 12 ), 48 mm x 34 mm – engraving on paper – Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Hieronymus Bosch – Triptych of Haywain (outer panels) 1512-1515 – Museo del Prado

The Flemish artist, Cornelis Massijs (1510 – 1556/7), triggered by the Beham Brothers and Schön, composed a series of twelve minute engravings depicting dancing cripples (1538). The engravings, each having a height of approximately 58 mm and a width of c. 45 mm, represent the first collection of images showing peasants and other unrefined figures to be created in The Netherlands. Though distasteful by today’s standards, they were deemed comical in the 16th century. The cripples, all considered beggars, came from various backgrounds; four peasant couples, four town couples, a dancing monk accompanied by a nun, musicians, and a soldier and his wife. Massijs illustrated a variety of handicaps: amputations, a club foot, deformed legs, and the like. Most of the figures make use of walking sticks or self-fabricated crutches. The images, four of which are shown below, present inelegant figures, in ungainly poses, exposing, even accentuating any and all imperfections. ( for information about the engravings – see below)

Two striking works, in all probability, by Cornelis Massijs form a bridge that leads to Pieter Aertsen (1508 – 1575), the first Dutch artist to paint the peasant in a commendatory fashion. Both works, engraved by Frans Huys (1522 -1562), were published after the death of Massijs. Peasant woman dancing the Egg Dance (1558) shows a somewhat older, coarse, peasant woman dancing in front of a tavern. The tavern guests are all unbecoming characters; each has a peculiar and uninviting grimace. And then there is a dog wearing a fool’s cap, the burning houses in the background, and the long rod with a hanging loop, extending from the roof of the tavern. All these elements intensify the impression that this tavern is a place of ill-repute. Cornelis Massijs confronts the viewer with a harsh message. Massijs construes the feast-loving peasant much in the manner of Hieronymus Bosch, as the symbol of frivolity, foolishness and impiety. The barren tree and the raging fire, very Boschian elements, offer a glimpse of the suffering the peasant’s levity will provoke.

A second engraving by Frans Huys, The Lute Player, was also designed by Cornelis Massijs. This interior scene shows an elderly woman, named Woman Longnose (explained in the text under the image), holding a lute without strings. She approaches the lute maker requesting that her strings be repaired. Master John Blokhead, as the lute-maker is called, cannot repair the strings because he must save the strings for another woman’s lute. Is he saving his strings for the woman just about to enter the door? Her lute has no strings. The innuendo is clear enough. If the owl is any indication, all is not well. In fact, the entire engraving is an allusion to licentiousness. And, as in many artworks of the time, dance is deployed to symbolize the peasant’s frivolous way of life. The frieze of illustrations decorating the mantel piece, inspired by Sebald Beham’s Dancing Peasants, effectively underscores the wanton transgressions of the peasants.

Pieter Aertsen, a contemporary of Cornelis Massijs, presented a proud, industrious peasant. His magnificent portrait, The Cook, depicts a young woman with a humble come-off in a pose that would befit a Renaissance lady or a Greek goddess. Aertsen, even before Breugel the Elder, ushered the common man into the foreground. In Village Festival (1550), Aertsen’s earliest image of peasants in the countryside, he paints a close-up view of three large figures. As customary in Aertsen’s work, a secondary space and even a third space, compliments or comments on the narrative taking place in the foreground. In this case, there is an ambiguous scene taking place in a room at the top of the ladder. Taking into consideration the suggestive position of the young peasant’s hand on the woman’s lap, the relationship between the front narrative and the secondary scene is obvious. More in the background, to the right of the brick construction, Aertsen heightens his commentary with couples caressing, merrymaking and dancing.

The first figure you notice in Aertsen’s Egg Dance (1552), is not the lanky egg dancer, but the imposing peasant and his female companion. They dominate the foreground. The light falling on both their faces demands attention. She is especially radiant. His grand physique virtually extends diagonally from top to bottom, covering half of the panel. Though the physical presence of the peasant may dominate the painting, an Aertsen artwork always alludes to, a-not-to-be-misunderstood, moral undercurrent. The Egg Dance abounds in double meanings. What at first appears to be a pleasant scene of rustics dancing and drinking in a tavern soon discloses another theme. The bagpipes, the hanging sausages, a jug filled with leeks, leeks lying on the floor, the open jars, the mussels and the playing cards on the table, are all subtle and less subtle symbols; there is more than meets the eye.

The egg dancer himself, slightly more in the shadows, dances to the rhythm of a bagpipe player; the bagpipes, a peasant instrument, symbolize the male genitalia. He performs his challenging dance amid leaks, mussels and an array of other erotic symbols. Aertsen’s Egg Dance takes place in a brothel; the dancer, the musician, and all the other occupants form but, an amusing facade behind which lies a moral message. The window scene (the vista behind the long peasant) and the family looking through the doorway form an unequivocal commentary on the bawdiness.

The composition of The Egg Dance and The Lute Maker, follow a similar structure; the principal scene is formed by a small group of figures presented in close-up. Behind them there is a fireplace with a heated cauldron. The entire space is laden with symbolism; both the lute-maker and the tavern guests suggest dubious behaviour. In the doorway, personages from the outside world gaze inwards. In The Lute Maker, the woman, a patch over one eye, has placed her strangely shaped foot on the threshold. She guides her listless little boy, who carefully holds his hobby-horse, into the unfamiliar space. In comparison, the parents, in The Egg Dance, stand firmly behind the door. Only the little boy endeavours to step into the tavern, but not without glazing for his mother’s approval. Are the parents showing their bright-eyed son a path to avoid or will this young lad succumb to temptation? Aertsen and Massijs have both designed a world of unmistakable sensuality. In the late middle-ages and early Renaissance, dance and dancers were associated with lust, the earthy and the depraved, and Aertsen and Massijs, whether painting a jolly egg dance, or reproducing a frieze of brazen peasant dancers, used this metaphor to the full.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1525 – 69) will forever be associated with peasant images. His most daring dance painting, The Peasant Dance (1568) was painted late in life. At a time when world landscape painting was popular, when feasts and celebrations were presented from a bird’s eye perspective, Bruegel positions the peasants in the foreground, at eye-level. Moreover, he boldly paints a monumentally sized peasant couple that rushes into the town square. They embrace a very significant section of the right side of the canvas. But even more remarkable, this unambiguous couple is shown from the back. In fact, they partially obstruct our view of the village square. No less stunning is the peasant dancer’s black jacket. For an early Renaissance artist to place such a considerable black zone, so prominently in the foreground is extraordinary, to say the least. Daring, absolutely! Innovative, undeniably. Bruegel has painted a stupendous couple, presented at eye level, with their backs confronting the viewer. The onlooker is essentially enticed to join in the festivities.

In little more than five decades, the image of the peasant dancer evolved from a miniature, lurking in the margins, to a fully pledged figure in the foreground. The church and the state gradually reconsidered their viewpoint on peasant dancing, but many years would pass before vulgar dance gained any form of acceptance. Bruegel was more sympathetic to the plight of the peasant. The Peasant Dance, however, though without question an innovative work, is not free from symbolism or social criticism. The following post will consider these issues.

Dancing Cripples – Cornelis Massijs – 1538 – engraving on paper – Visit THE BRITISH MUSEUM for the entire collection of twelve engravings

1) Two peasants walking to right with the aid of sticks – 58 mm x 45 mm

2) Two peasants walking to left with the aid of sticks – 58 mm x 42 mm

3) Two standing peasant musicians; right plays a hurdy gurdy, left plays the bones – 58 mm x 43 mm

4) A male and female couple dancing with crutches; he may be a soldier and has a wooden leg – 56 mm x 43 mm