Pieter Bruegel the Elder (c.1525/1530 – 1569), fondly referred to as Peasant Bruegel, had two sons; Pieter, born in 1564, and Jan, born in 1568. Both Pieter and Jan became celebrated artists. Pieter the Younger was an excellent artist and equally accomplished businessman; the greater bulk of his enormous oeuvre was centred around peasant themes. Pieter spread his father’s work, developing the peasant genre into an unparalleled success story. The younger son, Jan, also perpetuated his father’s legacy, as well as developing his own style, painting allegorical and mythological works, flower still life, landscapes, seascapes, and village scenes.

Bruegel the Elder passed away when his sons were very young; the brothers were taught the art of painting by their grandmother, the artist, Mayken Verhulst. The young artists, Pieter and Jan, had little opportunity of seeing their father’s paintings first hand; many of Bruegel’s works had already left Flanders during his lifetime to become part of prestigious collections throughout Europe. Pieter, however, immortalized his father’s work, reproducing literally hundreds of his paintings. How, you may wonder, could the brothers, having little to no access to their father’s original work, produce such faithful reproductions? To give an idea of the extent of the reproductions, Winter Landscape with Bird Cage has 127 documented copies, Battle Between Carnival and Lent, has at least eighteen known copies, Netherlandish Proverbs, at least sixteen copies, and The Peasant Wedding Dance, whether named Wedding Dance in the Open Air, Wedding Dance or a name to that effect has been copied more than a hundred times. Thirty-one copies are attributed to Pieter Brueghel the Younger or his workshop.

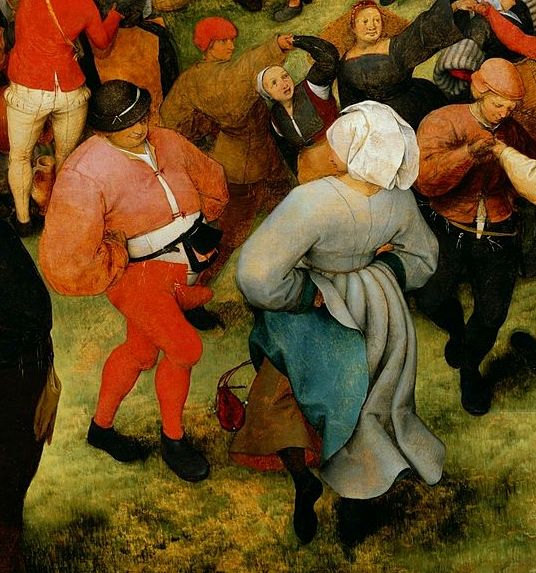

Ten years before Pieter Brueghel the Younger copied his first Wedding Dance, Jan Brueghel the Elder painted Outdoor Wedding Dance (1597). Pieter’s earliest replicas, from approximately 1607, are housed in the Walter’s Art Gallery, Baltimore and the Royal Museums of Fine Art, Brussels. Pieter occupied himself with this specific wedding dance theme from at least 1607 to 1624. The rustic dancers found in the reproductions by both Jan and Pieter are remarkably similar to the dancers in Bruegel the Elder’s Wedding Dance and Pieter van der Heyden’s engraving, inspired by a lost work by Bruegel the Elder, The Peasant Wedding Dance. In each reproduction, even though the background and the setting differ slightly, the colours and brush strokes vary somewhat, the dancers are virtually interchangeable. The four images, shown below, present an essentially identical detail of The Wedding Dance; each features the same prominent dance couple. The similarity of the man’s posture, leg placement, bent elbows, rotated wrists, clothing, and protruding potbelly, cannot be disputed. There are, understandably, some subtle deviations, the positioning of the head varies, the focus shifts minutely and the man’s hairstyle and cap undergo revisions, but the basic composition of the dancing man never changes. Likewise, his partner, whether facing the same direction or mirrored, is identical in movement, carriage, and build. A random glimpse of the dancers surrounding them reveals more duplication.

R: Peasant Wedding Dance – Pieter Bruegel the Elder (designer) – Pieter van der Heyden (engraver) – The Metropolitan Museum of Art – after 1570

R: Pieter Brueghel the Younger – Wedding Dance in the Open Air – 1607-14 – The Holburne Museum, Bath, United Kingdom

Pieter Brueghel the Younger headed a large workshop, employing a considerable number of apprentices, where patrons could commission their favourite artwork. During the 15th and 16th centuries, unlike today, copying a popular artist’s work was commonplace and absolutely acceptable. Replicas of the work of esteemed artists, such as Bruegel the Elder, were very much in demand. Artists and their apprentices utilized various techniques to replicate art works; cartoons were used to trace or pounce an outline onto a surface. The cartoon tracing technique was widely used in the Renaissance, as was the pouncing technique where the artist pricked small points onto a surface to later connect the points forming an underdrawing. The image below, an infrared reflectogram of a detail taken from The Battle between Carnival and Lent, divulges the pouncing marks flanking the underdrawing lines; the most perceptible pinpricks surrounding the border of the guitar.

Pieter Brueghel the Elder, as customary at the time, most certainly worked with preparatory drawings and practised the pouncing technique. Christina Currie(2), in her research, discovered that Bruegel’s sons reproduced well-known figures, including the iconic dancing couples, from their father’s drawings employing the pouncing technique. She suggests that Pieter and Jan inherited Bruegel the Elder’s preparatory drawings and cartoons, enabling them to reproduce the original figures. These cartoons, possibly due to extensive use, have not survived the passage of time. When superimposing one artwork over an equivalent artwork, Currie also discovered that the figurative compositions exactly corresponded, affirming that the figures must have been copied from the very same preparatory drawings. Even when the figures are mirrored, the form of the corresponding figures is indistinguishable. The archetypal dancing couple, presented in the four different images shown above, that were created over a span of approximately fifty years, by four extraordinary artists, confirms this point.

Left: Peasant Wedding Dance – oil on oak wood – 38.5 x 51.5 cm – 1607 – Royal Museums of Fine Arts Belgium, Brussels

Right: Peasant Wedding Dance – oil on panel – 1624 – Crocker Art Museum Sacramento, California

It is almost like playing the game, ‘spot the differences’. At first sight, the distinction between the two wedding dance paintings seems limited to colour and lighting. The dancers, the musicians, the silent observer and kissing couples are all completely familiar; the similarities outweigh the differences. Closer inspection (click on the images to expand) reveals very subtle modifications in posture (the silent observer), a slight shift of the head, variations in facial expression, minute alterations in spacing, but, essentially, the 1607 painting is identical to the 1624 version. The main difference lies in the setting and the background; I have not cropped the images. The 1624 painting has two unmistakable oaks, one rather spooky with extended roots, meandering upwards along the flank of the canvas. Glancing past the trees, a couple can be seen in the distance and to the right of the curved tree there is another woman. The earlier Brussels version is merely adorned with one oak, where, as in the Sacramento copy, two men peer around the tree, staring, like no other figure in the painting (as far as I can ascertain), straight out at the onlooker.

The above paintings are just two of the numerous works by Pieter Brueghel the Younger, presumably made in collaboration with artists and apprentices working in his atelier. Brueghel the Younger, an established artist in his own right, certainly understood the mechanics of the art market and capitalized on his father’s work. In doing so, he incessantly promoted Bruegel the Elder’s work and helped to embed the peasant theme, as a fashionable motif, in his lifetime and for the next century. Pieter Brueghel the Younger not only reproduced The Wedding Dance, but inspired by artists like Marten van Cleve reproduced and developed the peasant theme reprising paintings like the Presentation of Bridal Gifts, The Wedding Procession, and Wedding Dance in the Tavern.

Though unquestionably inspired by his father’s work, Jan, Bruegel’s younger son, designed an atypical version of a wedding dance. In this early work (1597), Jan combines the four iconic dancing couples, the bagpipe players (now without an oak to lean on) and the bride, in a traditional world landscape setting. The gently flowing stream leads the viewer’s eye past the cottage, along the woods, to the distant castle, and farther on towards infinite space. In the village, the bride is surrounded by many people, including a man relieving himself against a brownish wall or fence. As in other wedding dance paintings, there is a silent observer positioned in front of a man drinking thirstily from an earthen jug. Interestingly, Jan the Elder uses this motif a second time; to the right of the bride’s table the observer, standing as stationary as always, his hands clasped behind his back, surveys the drinking man. This country reveller blatantly enjoys his liquor to the very last drop. Why Jan Brueghel has chosen to use this motif twice is a matter of discussion, as is the presence of the well-dressed townsfolk standing near the banks. And what is the purpose of the enigmatic figure wedged in between two winding trees on the opposite side of the stream?

Painted slightly earlier than Wedding Feast in the Open Air, Jan Brueghel places the festivities, once again, in the world landscape tradition with picturesque vistas, churches, cottages, waterways, foliage, and a stream adorned with fluttering swans. There are no rustic peasants to be seen in this idyllic country wedding scene. The wedding guests, well-to-do rural folk and townsfolk, are refined, and the women are stylishly dressed in graceful, fine-spun robes. Behind the front layer there is a lot of activity going on. Groups of people are talking, some more intimately than others, children play, and though painted in a rather vague fashion, a man can be seen urinating not far from a mighty tree. But the focus is on the leading figures; the bride dancing with the groom, the musicians and an old man pointing towards the newlyweds. He looks directly out at the viewer, possibly inviting us to join in with the celebrations or, perhaps, questioning the prospect of the union; are the two dogs and the child holding a toy ring insinuating a potential misgiving?

Contrary to all the other dance figures discussed in this post, these dancers are light and vivacious. They stand tall and appear to bounce or spring lightly from foot to foot. The manner in which the man offers the lady his hand is reminiscent of a courtly dance. Their slender poise carries a certain elegance, especially when juxtaposed against the more unrefined couple dancing immediately behind them. That man, for the most part hidden behind the bride, moves heavily, kicking his feet ungraciously and flinging his arm, in peasant fashion, high into the air. The musicians, on the contrary, though one plays the typical peasant instrument, the bagpipes, are not the typical Bruegel/Brueghel musicians. Instead of two bagpipe players leaning, frequently in a sluggish fashion, against a tree, this wedding has three active musicians playing more genteel music, on the bagpipes, the flute and a string instrument, possibly a vielle.

Jan Brueghel the Elder carried on his father’s work in his own innovative way. Pieter Brueghel the Younger promoted his father’s work through reproduction and shrewd mechanizing. Pieter Bruegel the Elder epitomises the ingenious artist who transformed art in The Low Countries.

1 – European Paintings 15th-18th century Copying, Replicating and Emulating CATS proceedings, 1, 2012 – Pieter Brueghel as a copyist after Pieter Bruegel – Christina Currie and Dominique Allart

2 – Christina Currie – Head of Documentation and Scientific Imagery, Koninklijk Instituut voor het Kunstpatrimonium (KIK) in Brussel (Brussels), Belgium

Christina Currie – From Father to Sons: The Hidden Techniques Behind the Bruegel Success Story