There was a time when imitating and emulating a celebrated artist was common practice. There are, for example, 127 documented copies of Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Winter Landscape with Ice-skaters and Bird-trap. Bruegel’s The Wedding Dance, the subject of my previous post, was copied and imitated numerous times. Exactly how many copies were made is now unknown; some works have been lost, others are in private collections. His Wedding Dance in the Open Air, which has reached us via a print by Pieter van der Heyden, has been copied more than a hundred times. No fewer than thirty-one copies have been attributed to Bruegel’s son, Pieter Brueghel the Younger.

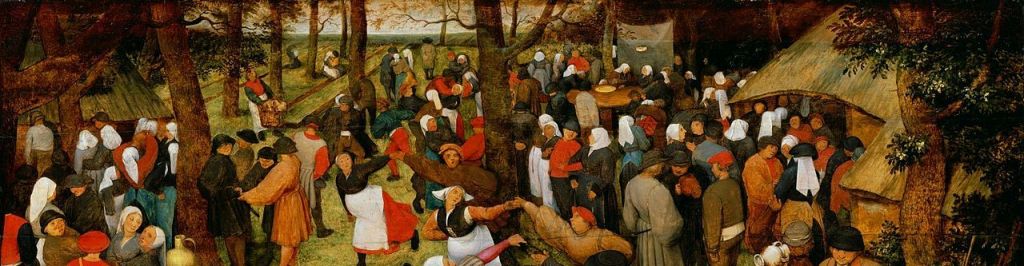

The Royal Museum of Fine Arts in Antwerp possesses an exceptional copy of The Wedding Dance in their collection. This painting, also named The Dance of the Bride, was formerly attributed to Pieter Brueghel the Younger. Dendrochronological analysis dates the work earlier than Brueghel II, and most probably copied shortly after the original work was completed. The anonymous artist was, unquestionably, familiar with Bruegel’s painting. The similarity with Bruegel’s work is striking.

The leading dancers, in form and composition, are direct copies of Bruegel’s original work, if slight deviations in facial expression be disregarded. Many of the non-dancing figures are thoroughly familiar. The scene is set, as in the original Bruegel, amongst a stage of oak trees. The Antwerp Wedding Dance/The Dance of the Bride, being eleven centimetres wider than the original Bruegel painting, is furnished with an additional figure behind the bagpipe players. Additionally the left side is demarcated with an extremely sturdy oak forming a dark ridge from top to bottom. Closer scrutiny, however, reveals some surprises; none of the male dancers appear to have protruding codpieces. This is remarkably interesting considering that this painting was presumably copied not long after Bruegel’s original work. Equally curious is that the background has undergone various changes; the bride’s table, so recurrent in wedding dance paintings, has disappeared mysteriously. New is a child being lifted high in the air and the two amiable dancers having a great fling as they swing to and fro. Next to them, a jolly rustic, possibly just slightly tipsy, enjoys his solitary hornpipe.

Even more unforeseen is that Bruegel’s infinite vista has been replaced by a congenial village scene, with the church steeple as the finishing line. There is, naturally, a logical explanation of these variables; The Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp, offers clarity. Apparently, in the second half of the nineteenth century, The Dance of the Bride was fitted with a new top panel; an encircled village setting. This considerably changed the viewer’s perception of the artwork by effectuating a higher perspective.(1)

There is no explanation for the whereabouts of the bride’s table. Was that ‘lost’ with the renovation of the top panel? A reasonable possibility considering that the panel has a width of 23.3 cm (9 inches). That raises the baffling question if the ‘extra’ dancers are the work of the anonymous 16th century artist or the 19th century restoration artist? If, in fact, the dancers are the work of the 16th century artist, it would be fascinating to know if these figures relate to Bruegel the Elder. And why are the codpieces, so decidedly prominent in Bruegel’s work, no longer conspicuous? This question, fortunately, can be answered; latterly the museum restored the painting, discovering that at some point in time, etiquette (or call it prudishness) demanded that certain aspects of the painting (read codpieces) be modified to be judged acceptable in polite society. The Dance of the Bride, after restoration, which involved the removal of the overpainting, is without doubt an awesome copy of Bruegel’s original work.

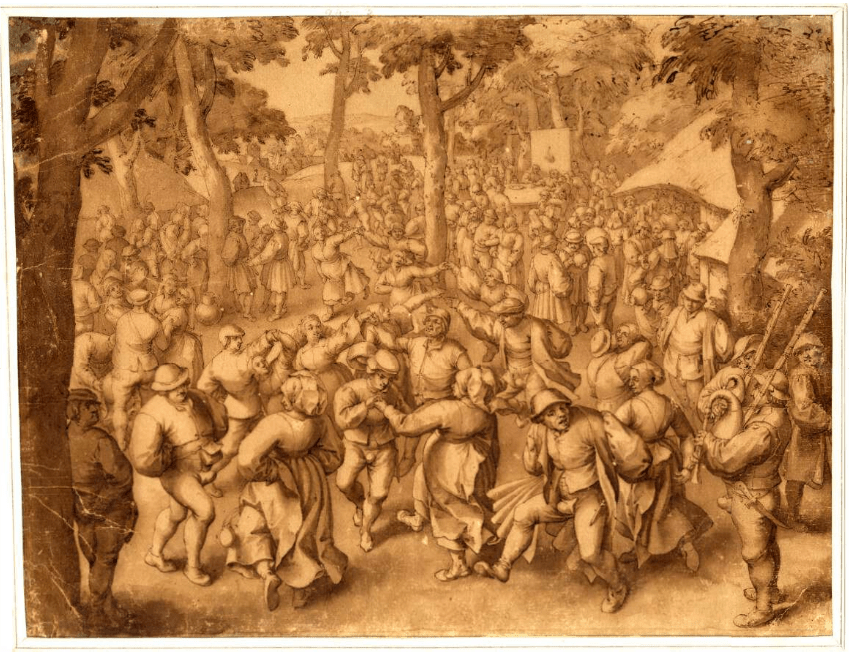

The Amsterdam-based Jan de Bisschop (1628 – 1672), by profession a lawyer, was in his free time an amateur draughtsman and etcher, copying, among others, the works of Tintoretto, Rubens, Van Dijk, and Pieter Bruegel the Elder. At first sight, you may deem his drawing a near copy of the Detroit painting, The Wedding Dance; the bride’s table has returned and the vista, though dissimilar, is unbounded. The ‘extra’ dancing couple, the jolly rustic, the young child and courting couples, all present in the Antwerp version, have vanished. Notwithstanding, certain elements of the Antwerp version have been retained. There is a distinct image of the rustic standing behind the bagpipe player.(2) Furthermore, in contrast to the Detroit painting, there is a clearly visible thick oak tree on the left-hand side that stretches out over the entire length of the drawing. That old oak has not only grown a number of extra branches, but gained many more leaves; in fact, all the trees are visibly higher and all bear greater foliage. Not unexpectedly, this gives rise to an altered vantage point; the onlooker has a bird’s eye view. Jan de Bisschop, some hundred years after Bruegel, has painstakingly created a sincere copy of The Wedding Dance. One can merely wonder which painting or paintings inspired him.(3)

Peasant weddings were one of the most popular themes in 16th and early 17th century Flemish art. Pieter Bruegel’s contemporary, Marten van Cleve (c.1527-1581), composed a considerable number of paintings depicting various aspects of the peasant wedding; wedding processions, the presentation of the wedding gifts, the blessing of the bridal bed, and the wedding feast. His version of the wedding dance, named An Outdoor Wedding Dance, though, in part, similar to Bruegel, is in composition, style, and subject matter, an original work. The scene, set on the outskirts of a village, shows a wedding feast in progress. This is a family event, including quite a number of youngsters and even a mother nursing her baby. The tables are filled with various dishes and drink is plentiful. The man sitting at the lower end of the right-hand table is definitely under the influence. There is a good deal of drinking, kissing, cuddling, and caressing taking place and one may query the intentions of the young couple passing under the farmhouse passageway.

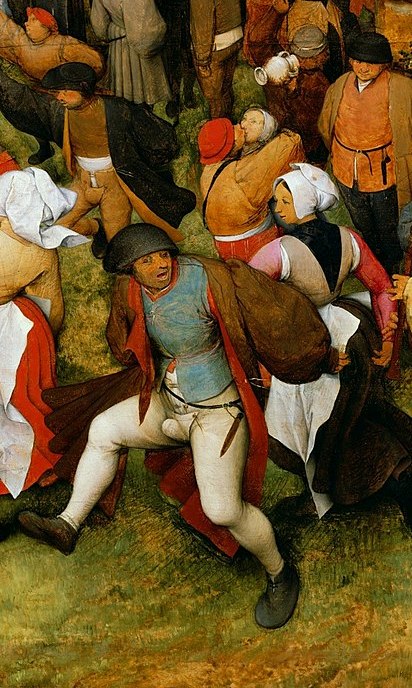

Pieter van der Heyden – The Peasant Wedding Dance – after Pieter Bruegel the Elder – after 1570 – Metropolitan Museum of Arts, New York – detail

Marten van Cleve the Elder – An Outdoor Wedding Dance – Sotheby’s – detail

Marten van Cleve reduces the dancing party to four couples; the dancing figures in the foreground derive from Bruegel. The bride, familiar from Bruegel’s work, now dances with a considerably younger man. She, in contrast to Bruegel’s bride, is a little reserved and her partner (the groom?) seems overwhelmed by all the festivities. The centre couple and the couple dancing next to the bagpipe players are familiar in manner, deportment, and dress. The fourth dancing couple, the back to back figures, do not appear in The Wedding Dance, but are characters rollicking in The Peasant Wedding Dance, a print by Pieter van der Heyden. This image is faithfully based on a lost artwork by Bruegel. This elderly couple is a cruder, brusquer, version of the figures featured in the 1566 painting. The man, a rugged character who carries a knife just above his waist, is far less sprightly than his earlier counterpart. He is earthbound, ponderous and manoeuvres heavily on his awkwardly bent knees. Yet despite his cumbersome carriage, he nonetheless manages to grasp his partner’s behind. The shabby woman, void of any charm, slants slightly forward in anticipation of her partner’s next movement. This peculiar couple, icons themselves, appear in practically every version – whether works by renowned artists, followers or anonymous artists – of paintings generally named The Outdoors Wedding Dance or Wedding Dance in the Open Air or variations thereof.

In The Peasant Wedding Dance, the bride no longer dances. She sits tranquilly at her table watching the festivities or counting the coins given to her by the guests. Familiar guests – the stocky dancers, the kissing couples, the drinking men, the observer, the bagpipe players – all appear and reappear in the more than a hundred copies of this painting. Whether titled The Outdoors Wedding Dance, Wedding Dance in the Open Air, or The Peasant Wedding Dance, Bruegel’s rural image with his glorious, rustic dancers is a blockbuster.

(1)As a matter of interest, recently researchers working at the Detroit Institute of Arts discovered that the horizontal panel at the top of The Wedding Dance – a 2.5 inch strip of wood (approx. 6.35 cm) – was not part of the original 1566 painting. The actual appearance of the original top layer of the painting remains open to speculation.

(2) I must mention that in the Detroit The Wedding Dance there is also a figure standing behind the bagpipe player. This figure however is cropped, stands in the shadow and in no way as obvious as either in the Jan de Bisschop drawing or in the Antwerp painting The Dance of the Bride.

(3) The RKD Netherlands Institute for Art History has an amazing collection of images, including a number known and lesser known versions of The Wedding Dance; The Berlin Version, a version freely inspired by Bruegel I and finally a version once in the collection of art dealer Linker, Madrid/Bilbao.