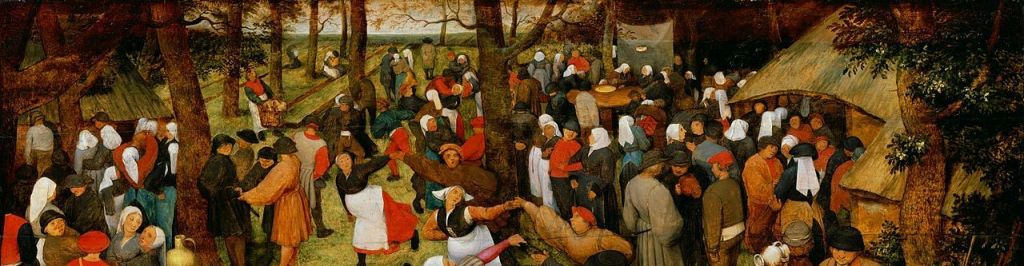

The peasant wedding was a popular theme in 16th and early 17th century Flemish art. Paintings of wedding processions, the presentation of wedding gifts, the blessing of the bridal bed, and the wedding feast flooded the art market. Images of a wedding dance, with exuberantly dancing peasants, were especially in demand. Bruegel composed two versions. One version, which will be discussed in this post, is housed in the Detroit Institute of Arts and presents the bride dancing enthusiastically with her guests. The other version, where the bride sits sedately at her table, has reached us via a print by Pieter van der Heyden, after Pieter Bruegel the Elder. The original painting, if there was one, has been lost. The foreground of these two works is reserved for four imposing dancing couples. Three couples appear on both artworks. The fourth couple differs, though in each version they dance back to back. Bruegel’s wedding images became a market commodity. His work was freely imitated, copied, revised and served as a source of inspiration for subsequent artists.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder revolutionized the art of painting peasant life and peasant dancers. His Wedding Dance is iconic. In this magnificent panel, Bruegel presents an outdoors marriage celebration. The viewpoint, as was customary at the time, is relatively high, with the horizon located just below the top of the picture. The composition, consistent to a world landscape, is layered. A circle of trees encloses the foreground, where to the accompaniment of two bagpipers, rustic peasants dance and make merry. Directly behind them, more dancers, including the bride, dance in what appears to be a reel. The bride can be recognized by her dark dress and her free-flowing hair. In the area behind the oaks, we find more guests; many of them gathered in the vicinity of a cloth of honour that is suspended between two trees. Traditionally, the bride is seated at the table to greet her guests and receive gifts, but in this Wedding Dance she dances heartily. Bruegel then leads the viewer’s eye along elongated rectangular ‘tables’ farther into the distance. And once you spot the man, his back towards the viewer, looking tranquilly out into vast space, you discover yourself unwittingly gazing towards the horizon.*

Bruegel’s Wedding Dance is original, innovative, and groundbreaking. That is not to say that peasants and peasant dancing had not appeared in earlier art works. Peasants were infrequently seen as drolleries, marginal figures decorating illuminated manuscripts. In German art, peasants, often of gross and uncouth character, appeared on prints. And not to forget the acclaimed Dutch artist, Hieronymus Bosch, whose enigmatic paintings contained isolated peasant scenes. Dancing peasants appear in a number of his works; possibly the best known is the dancing couple on the outer shutters of The Haywain. In all the examples mentioned, with the exception of Albrecht Dürer‘s prints, the dancing peasant is but a minor element of the narrative. Invariably, the rustic is a background figure, frequently employed as a metaphor inferring a moral or didactic concept. Bruegel placed the (dancing) peasant at the centre of attention; he became the key subject of the artwork. The Wedding Dance, painted around 1566, is all about peasant life, highlighting the day-to-day existence of the peasant as they dance, talk, drink, and amuse themselves, celebrating a country wedding.

If I had not mentioned that the bride is wearing a black dress and has long flowing hair, you may not have noticed her. She, traditionally the centre of attention, is not the first figure that catches the eye. Bruegel gives that privilege to the three large dancing couples in the foreground. The bride and her dancing guests are situated a little farther back. They dance in pairs, holding their clasped hands high in the air, to form a bridge. In turn, each couple passes under the passageway. These perky dancers are smaller than the bold group in the foreground, and, except for the bride and her partner, have less individuality. Bruegel offers little information about the steps and movements. Only two clues; the chap, wearing a black half-clock, lifts his legs in a sprightly fashion and the couple, in the vicinity of the large oak, perform rapid, running steps.

The distinctive front couples are the most robust and largest figures of the entire panel, clearly towering over the bride and her (dancing) partner, not to mention all the other figures descending into the background. The leading women, all three with their backs to the viewer, practically form a horizontal line. The centre woman immediately makes an impression; her white apron and headdress stare you in the face. She, like the villager next to her, is a lively dancer. The young woman dances in unison with her partner, both kicking their legs into the air, bouncing from foot to foot. The peasant woman in blue curiously lifts her skirts, displaying not only her underskirt but also a small purse. Her partner, a sturdy rustic, is under no circumstances light-footed, dancing as if being weighed down. The man’s expression is more than a little suspect. Revealing only the figure’s left eye, Bruegel ingeniously discloses the character’s intentions. If this is too subtle the extended codpiece and open pouch, carried conveniently just above the codpiece, will dismiss any doubt.

The couple on the right, moving practically back to back, dance unlike any of the other rustics. The countrywoman, if the tossing action of her skirt gives any indication, moves briskly. Contrary to the other women, who lean backwards thrusting their pelvis well forward, this woman projects forward in a gentle diagonal slant. Of the three women, only her face is visible. This fine featured peasant woman, looks over her shoulder at her conspicuous partner, whose astonished expression makes one wonder what he is looking at. He certainly is the nimblest of the male dancers, kicking his leg into the air, rotating his body, and all the while flinging his arm backwards to grasp his partner’s behind. He, too, you will have noticed, wears an exaggerated codpiece. And then there is the musician; this fine man plays the traditional peasant bagpipe, considered by church and local authorities to be a lewd instrument symbolizing rowdiness and bawdiness. The musician, unmistakably present at the front of the painting, cannot escape the viewer’s attention.

Peasant life was often portrayed disparagingly. Peasant dance was considered to be lascivious and immoral. Sometimes, however, dance was more or less permissible. Martin Luther, for example, accepted dancing at weddings, seeing no reason to condemn it ‘save its excess when it goes beyond decency and moderation’. Dance, nevertheless, was generally frowned upon. Many art works in Bruegel’s time openly mocked and ridiculed peasant-life, frequently drawing attention to the coarseness of the dancing peasant. Artists chose to admonish the peasants ‘vulgar’ customs. Bruegel was milder than his predecessors and most of his peers. He never preached. He neither condoned nor criticized the peasant. Rather, he was a discrete observer with a superb sense of humour, combined with pragmatic ambiguity. The result; the most iconic rustic dance figures of Renaissance Low Countries.

* After I had finished this post I found some interesting additional information discovered by researchers and curators working at The Detroit Institute of Art. In preparation of the exhibition Bruegel’s Wedding Dance Revealed (2019), researchers discovered that the horizontal panel at the top of the painting – a 2.5 inch strip of wood – was not part of the original 1566 painting. The research found that this section lacked the underdrawing, so prevalent in Bruegel’s original work. Furthermore, the pigments in this section are more coarsely ground. The additional panel was, according to the conservators added within the first two hundred years after Bruegel completed the painting.