Pieter Bruegel the Elder (c. 1525 – 1569), fondly referred to as Peasant Bruegel, showcased the peasant in his rural surroundings. His celebrated peasant panels, The Wedding Dance (c. 1566), The Peasant Dance (1568), and The Peasant Wedding (1566-69), painted in the last years of his life, form but a small section of his oeuvre. These three paintings, however, established his legendary fame as the artist of peasant life, all the more that his sons, Jan Brueghel the Elder and especially Pieter Brueghel the Younger further developed their father’s peasant theme. In fact, Bruegel’s overwhelming popularity can, in part, be attributed to the many recreations and imitations painted by Pieter Brueghel the Younger, his workshop and numerous 17th century artists working in Flanders.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder was by no means the first artist to paint peasant life, but where earlier artists turned to a bird’s eye perspective, filling the canvas with a multitude of miniature figures, Bruegel placed the peasant prominently in the foreground. He, as no other, revolutionized the manner of portraying peasant life and peasant dancers. This post will focus primarily on Bruegel’s dancing figures. In the first instance I will concentrate on The Wedding Dance housed at Detroit Institute of Arts which, according to most experts, is the original Pieter Bruegel the Elder work. I must mention that there are reproductions and different versions of The Wedding Dance. Images found on the internet or elsewhere may be the work of Pieter Brueghel the Younger or an array of different artists.

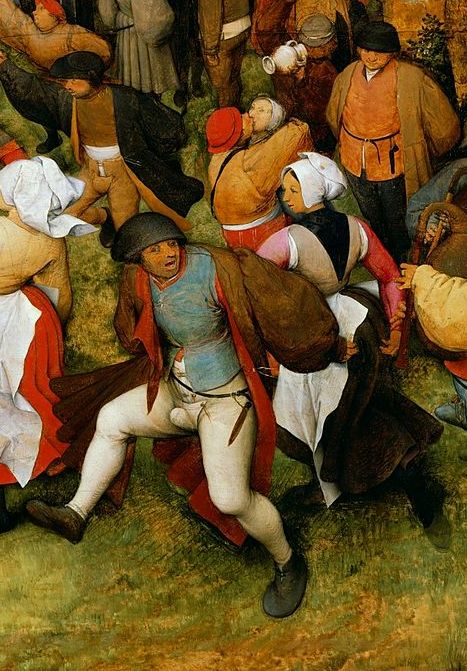

The Wedding Dance, in contrast to The Peasant Wedding and The Peasant Dance, takes a slightly heightened view; not unlike a photographer trying to capture as many people as possible within his lens. The front plane is entirely occupied with dancers. These colourful, rather stocky figures, are the centre of attention. This, in itself, is remarkable since, at the time, rustic dance was frowned upon, even considered immoral by local authorities and the church. Many artists, before Bruegel, represented dance as a disreputable activity. Bruegel was milder. He remained a detached observer; experts suggest that the non-participating man, standing behind the hugging couple, may be Bruegel himself observing the festivities.

Bruegel, the artist/historian Karel van Mander writes, was known to gatecrash peasant festivities disguising himself as a peasant. Undoubtedly, he had visited feasts similar to the one portrayed in The Wedding Dance. Bruegel illustrates at least eight dancing couples in his bustling feast. These dancers are accompanied by, not one, but two bagpipe players. From a practical viewpoint, considering that this wedding feast is outdoors, two musicians are most welcome. But, apart from the louder volume, hiring two musicians could imply that no expense was spared at this country wedding.

The dancing couples featured are now iconic: an overview

- A couple dancing back to back; different, but reminiscent of Albrecht Dürer’s famous print Peasant Couple Dancing (1514). The man, a rough type, has a striking expression. He flings his arm to the back, grasping his partner’s behind.

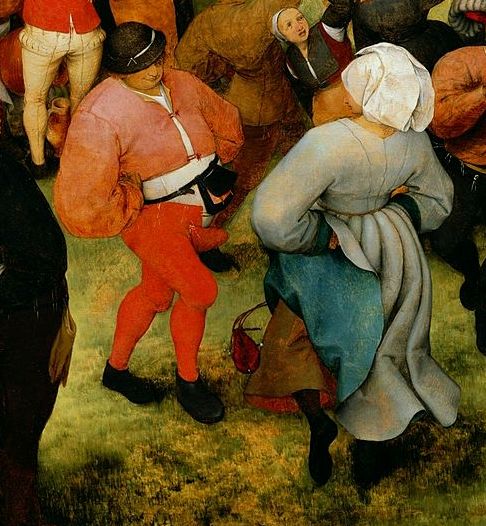

- A stocky couple that face each other, yet maintain a slight distance. Their hands are firmly placed on their hips. An alluring couple, no doubt; it is impossible to neglect the forceful forward pelvis thrust and the pronounced codpiece. The man faces the front and the woman, who invariably lifts her skirt to the waist, is shown from the back. His face is partially visible, and she unfailingly has a purse dangling around her knees.

- A couple facing each other holding one or, though difficult to see, both hands. This man faces his partner, but is preoccupied with his feet. His focus is downwards. She, on the other hand, gazes at her escort. The woman, in movement and deportment remarkably similar to the woman next to her, is shown from the back. She, however, neither lifts her skirt nor displays a purse.

- A couple where the woman turning under her partner’s uplifted arm. The man is seen from the back; his head is turned to the side as he guides his turning partner. The face of the woman, wearing a white cap, is in full view.

- Just a little farther back, various couples dance side to side; their arms placed well above shoulder height. All the dancers face the same line of direction. They appear to be moving forward.

- And finally, there is a couple who may or may not be dancing. They are to be found in practically every version of The Wedding Dance. They either kiss or hug, and notably, are invariably in close vicinity to a motionless bystander who quietly observes the festivities.

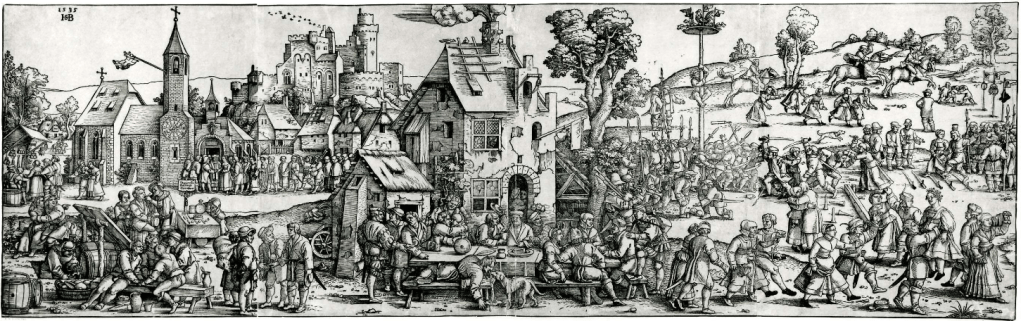

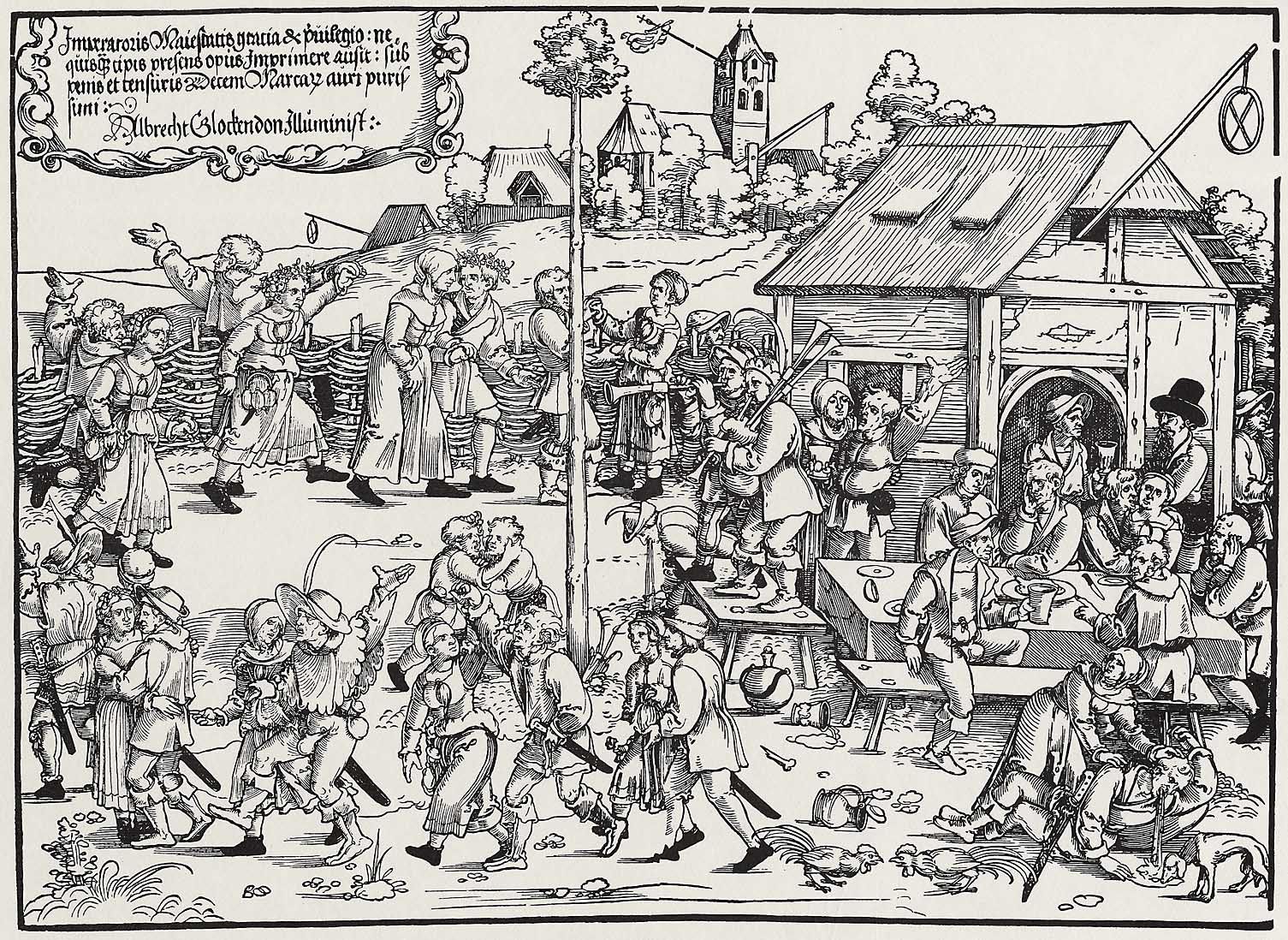

The formations, patterns and movements of these dancing figures were not unfamiliar to the Bruegel or his Flemish peers. German artists had been inspired by peasant scenes from the opening decades of the 16th century. I have already mentioned Dürer’s peasant dancers, but, for those who have read my previous post — Pieter Bruegel’s dancing peasants – a little background — will recollect the peasant dancers depicted by the Sebald and Barthel Beham and Erhard Schön. Take, for example, Sebald Beham’s woodcut The Village Fair. This work illustrates a wedding procession together with a variety of other activities. Peasants are presented as foolhardy and coarse; drunkenness, gluttony, sensuality and other vices inhabit the image. Dance, a lustful preoccupation, is one of the myriad of activities shown. The dancing couples, situated on the lower right plane, each has a distinctive contour. Some dance side by side, another pair is turning, others are skipping or hopping forward, and on the outer right a couple is dancing back to back. There is also a hugging couple and the most unusual, if not most immoral, is women is being lifted into the air. All these figures, with the exception of the immodest lift into the air, appear as fully fledged figures in Bruegel’s Wedding Dance.

But how does Bruegel’s representation of the dancers differ from other artists? Why are Bruegel’s dancing peasants so innovative? The most obvious answer is that Bruegel’s dancers dominate the foreground; they are large, imposing and tower over all the other revellers. The viewer immediately interacts with the various personalities. Furthermore, Bruegel has left a large open space in the centre of the panel, encouraging the viewer to enter into the festivities.

Bruegel’s Wedding Dance, you may say, is more accessible than an engraving, etching, or a print. Equally, you may point out, that Bruegel’s colour scheme, utilizing a repetitive rhythm of red, orange/brown and white is more than striking. But would you not agree that Bruegel has provided his dancers with a three-dimensional quality hitherto reserved for figures other than peasants?* Bruegel’s dancers are realistic, real-life figures that with a little imagination, dance a jig, spring up and down, swirl, stamp, and flirt. Their movements are decisively natural; movements that can be recognized in so many forms of dance, whether danced on a village square in the early Renaissance or during a 21st century dance event. From the inclination of the torso, to the pelvic thrust, the lifted knees, the sensation of weight, to a variety of twists and turns, Bruegel has epitomised movement on the canvas.

Left: Sebald Beham (or Bethal Beham) – Peasant Feast – 1532 – University Library Erlangen, Germany (detail left half) & Right: Pieter Bruegel the Elder – The Wedding Dance – c. 1566 – Detroit Institute of Art, Michigan (detail)

Bruegel’s paintings were immensely popular among townsfolk and the upcoming bourgeoisie; unquestionably the effervescent dancing peasants were fashionable and highly marketable. Responding to the constantly increasing demand, Pieter Brueghel the Younger, inspired by his father’s drawings and paintings, reproduced The Wedding Dance, often making near copies, and just as often adding his own personal touches. Occasionally, Bruegel’s other son, Jan Brueghel the Elder, known for his religious and floral work, also followed in his father’s footsteps. The dancing figures, so widely admired, had deservedly conquered a permanent prominence on each reproduction.

Right: Pieter Brueghel the Younger – Walters Art Museum – Baltimore – Peasant Wedding Dance

Right: Pieter van der Heyden – The Peasant Wedding Dance – after Pieter Bruegel the Elder – after 1570 – Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Wedding Dance enticed buyers, sellers, and artists; its widespread market value induced many, often less talented, artists to launch their versions and handle them at the local art market. Bruegel’s work has more than a hundred known copies. Many museums, worldwide, house a version of The Wedding Dance. Some versions have been signed by the artist, others attributed to a particular artist, and yet others, remain anonymous. But, what the case may be, all the artworks feature splendid dancing figures created by the innovative Flemish Renaissance artist, Pieter Bruegel the Elder.

*The Dutch painter Pieter Aertsen painted impressive peasant scenes slightly earlier than Bruegel the Elder. The peasant theme, in genre painting, took a firm hold in the second half of the 16th century. Pieter Aersten’s Egg Dance (1552) radically places the peasant and peasant life as the main subject of the painting. Progressive as he was, Aertsen seemed suspended between the old and the new worlds, interweaving a religious undertone into his work. Bruegel the Elder established the peasant genre as an independent art form.