Joachim Patinir, (c. 1480 – 1524), pioneer of Flemish landscape painting, created imaginary panoramic landscapes invariably envisaged from an elevated position. These fantasied landscapes, the world landscape, depicted high cliffs and rugged mountains juxtaposed against meandering rivers, extensive fields, flowing meadows, distant castles, and far-away villages. Biblical, historical or mythological figures often enhanced the foreground, but were unfailingly dwarfed by their overwhelming surroundings. Patinir never painted dancers. One of his successors, Jacob Savery 1 (1566 – 1603), however, composed a world landscape featuring the biblical narrative of Jephtahah’s Daughter. The scripture relates that the daughter, dancing triumphantly, was the first to welcome her father on his return from a victorious battle. The daughter, not named in the Bible, was unaware of her father’s sacred pledge to God. Jephtahah, if victorious, would sacrifice the first person he saw on his return home. This highly dramatic story is allotted a compact space in the lower left corner of the painting. Jephtahah, his daughter, her companions and the soldiers are overshadowed by the towering port and totally upstaged by the awe-inspiring landscape. And then to keep in mind that this is a small painting (18.5 x 31 cm); you can imagine how tiny the figures actually are in relation to the surrounding panorama.

Jacob Grimmer (c. 1525 – c. 1592), celebrated for his landscapes and cityscapes, moved away from the imaginary world landscape to develop a more realistic landscape. That is not to say that a 16th landscape painting was necessarily a realistic portrayal of the actual panorama. View of Kiel (1578), though painted from the customary high vantage point, definitely presents a more authentic image. Grimmer, however, still chooses to include riveting elements, adding an enclosed garden estate and a procession of rollicking peasants and city folk. This scattered parade, consisting of gallivanting rustics and heavily laden horse carriages, occupies the entire foreground. Amid all this turmoil, there are four dancing couples performing a vigorous dance. So vigorous, in fact, that one of the sprightly women has fallen. The others, regardless, are still hopping and springing happily to the music of the bagpiper. Or there is always the possibility that the sweet tune played by the apparently languorous lute player, reposing in the pursuing carriage, is spurring them on.

A green haze hovers over Hans Bol’s River Landscape. Here, as in Bol’s Flemish Kermesse, a work featured in the previous post, the viewer looks down over the panorama from an elevated vantage point. The disquieting clouds, the boats sailing on the river, the undulating hills interspersed with a manifold of trees, together with churches and distant villages constitute the greater part of the painting. The most distinct personages occupy the two lower corners; on the left side, well-dressed townspeople and on the right, a beggar beseeching a pair of peasants.

The lower right half of River Landscape illustrates a village feast; a close look reveals a celebration in front of the church, various market stalls, at least one drunken man, ruffians fighting, and, not surprisingly, a bagpipe player leaning against a maypole. He accompanies the dancing couples enjoying themselves in front of the tavern. The figures are minute. You can just manage to recognize the familiar motives — the closed position couple, the hand in hand couple and the swirl under the arm couple — so often seen in village festival paintings. These and all the other figures are none other than staffage, adding a touch of human interest but, nonetheless, merely a subordinate element.

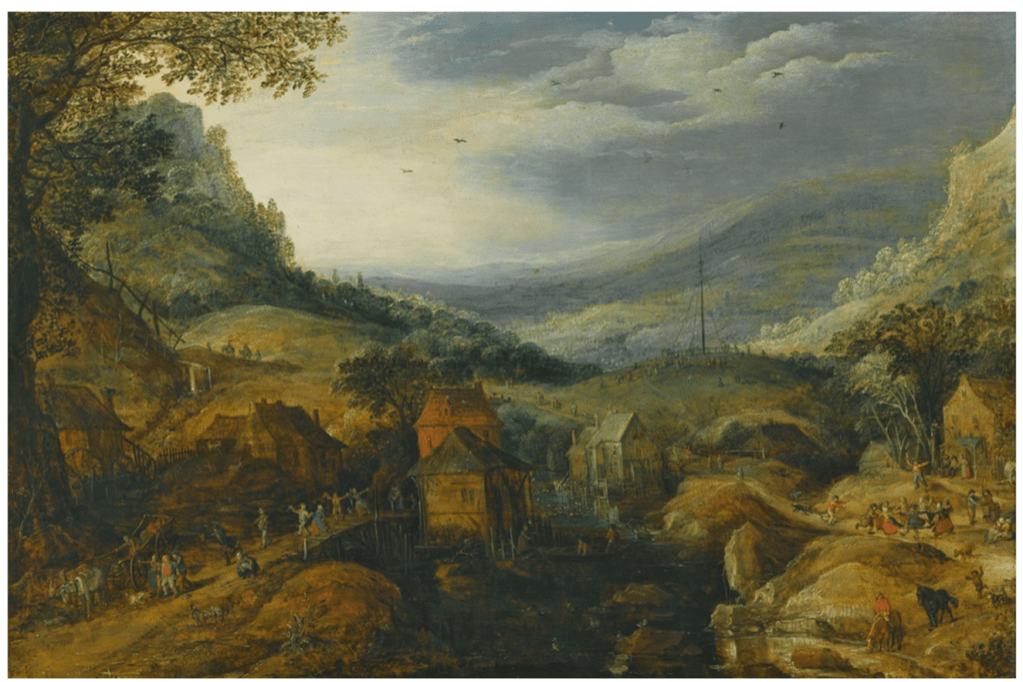

The figures in the following landscape, painted by Antwerp-born Joos de Momper (1564 – 1635), are still to be considered as staffage, but these rustics and their animals are distinguishable and not, as in River Landscape, little more than a swift, barely discernible brushstroke. Joos de Momper was a prolific artist specializing in landscape painting. He frequently collaborated with figure artists — Jan Brueghel the Elder, Jan Brueghel the Younger, David Vinckboons — to complement his landscape with decorative figures. Experts have suggested that David Vinckboons (1576 – c. 1632), himself an artist of many village scenes, painted the figures.

The expanse of light instantly captures the viewer’s attention. De Momper designs a limitless vista. Gradually one becomes aware of the rolling hills and undulating valleys. Slowly but surely the peasantry, apparently enjoying a festive day, comes into view. On the top of the hill, a large group of countrymen dance around the maypole. These figures are small, but their movements are recognizable. Moving down the hill, past the cottages, a tavern scene emerges. Next to some dogs, running men, and an amorous couple, a group of lighthearted figures dance a jovial circular dance. The bagpipe player, who accompanies them, is seated on what appears to be a barrel of beer. The figures may be tiny, but each dancer performs an individual movement. You can clearly see the men kicking their legs into the air and some of the women are pulling backwards and others intentionally pushing forward. Small as they are, the artist has given these staffage figures a specific personality. On the other side of the painting, a third dance scene is in play; couples crossing the bridge dance and caper to the beat of the hurdy-gurdy. Just in front of the frolicking dancers, the artist has added a few less subtle elements. There is an elderly woman relieving herself on the roadside, a fellow spewing and a man very much under the influence.

I am discussing Pieter Bruegel’s The Magpie on the Gallows (1568) last, though chronologically, it is the oldest of the paintings discussed in this post. Painted at a time of political, social, and religious instability, the painting is often read and discussed as a social critique denouncing the powers of the day. The Low Countries were, at the time, under Spanish control, leading Phillip II to send the Duke of Alfa to reinforce the Spanish dominance by means of persecution and oppression.

If, for just one moment, we disregard the gallows and the provincials, we find ourselves viewing an enchantingly serene landscape. There are mountains, cliffs, sweeping valleys, ancient castles, a meandering river and an all-embracing sky, graced with a handful of birds. Moving down the valley, on the right of the panel, there is a farmhouse, complete with a water mill, a peasant and farm animals, and still further, next to the river, a small but beautifully designed building. To the left, a road leads to a village which is depicted with immaculate Flemish detail; the panorama is in every aspect a world landscape.

But how can you possibly ignore the obtrusive gallows? This awesome contraption stands brutally in the centre of the panel, dividing the work into two distinct sections. On the right, a spacious valley where nature reigns and on the left, village folk, including, just barely concealed, a peasant defecating. And, resting on the gallows, the magpie, no doubt an allusion to gossiping tongues.

The dancers remind me, in style, build, and dress, of the dancers portrayed in Bruegel’s earlier works, Fair at Hoboken and Kermesse of St. George. In Hoboken, though, the peasants dance energetically in a large circle and in Kermesse couples dance next to the local tavern. The dancers near the gallows are unique in that they form a circle of three; a composition, to my knowledge, not seen elsewhere in Bruegel’s work. Jolly as this threesome appears, dancing in near proximity to the gallows, raises questions; they could have danced anywhere in this vast landscape. Scholars offer various answers, one being ‘the peasant dance represents the Netherlanders’ imprudent folly in face of impending danger‘.* Or perhaps, Bruegel’s dancers can be seen as a form of social protest, addressing the authorities (church and state) for their condemnation of dance and their denunciation of peasant fairs.

The Magpie on the Gallows was one of Bruegel’s last, if not his last, works. In both The Wedding Dance and The Peasant Dance, Bruegel revolutionised art by depicting large dancing figures, not from a bird’s eye perspective but practically from a frontal view. Viewers were virtually invited to enter into the festivities. In The Magpie on the Gallows, Bruegel has chosen a high vantage point, encouraging the viewer to contemplate the serenity of a timeless landscape and, in the same instance, confront them, metaphorically, with the perils that the people of The Low Countries were subjected to.

* Stephanie Porras – Resisting the Allegorical: Pieter Bruegel’s Magpie on the Gallows – re.bus issue 1 Spring 2008