If you have the opportunity of visiting the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, be sure to see Peeter Baltens A Flemish Kermis with a Performance of the Farce “Een cluyte van Plaeyerwater“. This, one of the earliest Flemish paintings of a village feast, presents a panoramic view, from a bird’s eye perspective, of a multitude of festivities and activities celebrating a religious holiday. The artist Peeter Baltens — also written as Pieter Balten — (c. 1527-1584), although less well known than Pieter Bruegel the Elder (c. 1525-1569), was, in his time, an acclaimed artist. Research has shown that Bruegel was, at one point, Baltens assistant in an important church commission. Baltens and Bruegel were esteemed artists whose careers often intertwined; both artists performed a paramount role in the creation of a new Flemish/Dutch art genre, the village festival.

The bustling energy of Baltens’ large painting is remarkable. At one glance we see a religious procession, a cart loaded with boisterous peasants, a row of market stalls, a tavern abounding in jolly customers, animals, a fool followed by children, dancers, and a portable stage. Typical of Baltens work, are the clearly rendered figures painted in spirited hues; red, especially, as the most distinguishing colour.

Amidst the overwhelming hustle and bustle, there are two instances of peasants dancing. On the outer right revelling peasants, dash, run, gallop, or suchlike, in a labyrinth path moving to wherever space permits. The front dancer, an outgoing fellow, points the way. This energetic dance represents a Farandole, one of the commonest early dance forms. By slanting a few of the dancers sideways, Baltens conveys a vibrant sense of forward motion. The dance steps, nor the direction of movement, is complicated; this is a community dance where young children can easily join. On the opposite side of the painting, next to an eating establishment, couples dance together. Their movements are iconic; the forward bend of the body, the graceless lift of the legs, their earthbound steps, and the weighty gait are all familiar. These frolicking, robust figures have an archetypal bearing, enjoying a distinct style of dancing. Figures, like these, are frequent participants in village festivals and village weddings.

Left – detail of Farandole with drummer as accompanist

Right – detail of couple dance with a bagpipe player standing next to a wall

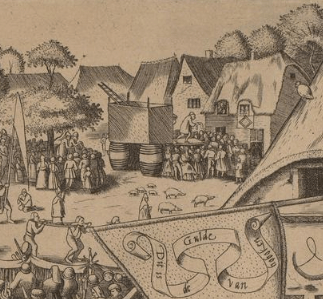

Travelling actors often visited village festivals performing, popular, mostly comical, down-to-earth plays, on a makeshift stage. Baltens’ painting is the first known Flemish representation of a stage performance where the actual construction of the stage is accurately depicted. The stage floor is positioned on four large barrels, upon which four long poles are placed. Four more poles support for the curtains. The curtain facing the onlooker is decorated with a floral pattern. Most interesting is the stage curtain, suspended on rings, giving us a glimpse of the prompter keenly following the text. That same curtain also functions as the wings, allowing actors to appear on and retire from the stage. The playing area itself, claiming half of the wooden floor, is just large enough for the actors and a few props.

I must point out that both Pieter van der Borcht and Pieter Bruegel the Elder, artists I discussed in my previous post, have included an image of a stage performance in their village kermesse prints. However, in each case, the image is located in the background, at the far end of the village square. These images show absolutely no detail and provide no clues as to which play the actors are performing. In fact, we are left wondering if we are looking at a theatrical performance or at an illustration of a quack peddling his wares. Baltens, in contrast, draws the stage and the performers to the foreground, placing the action in full view of the onlooker. The scene illustrates a cuckolded husband, who, helped by a local vendor, finds his unfaithful wife kissing the village priest. Baltens paints the dénouement of the narrative; the husband can be seen peering out from the pedlar’s basket. This popular farce, comical as it was, had infidelity as its theme. And what to think about the wife kissing a priest? This action alone raises many issues. Street theatre unquestionably provided hilarious entertainment, but an entertainment combined with didactic undertones and a generous dose of social criticism.

The theme, peasant festivals, gained immense popularity in Breugel’s and Baltens’ time. Baltens’ painting, exuberant, humorous, even a little unrighteous, was in demand. The painting became a prototype for the numerous copies, reproductions, imitations, adaptations: an inspiration to both Baltens’ peers and ensuing artists. Many — possibly more than twenty — versions appeared on the art market. Bruegel’s son, Pieter Brueghel the Younger (1564/5 – 1638), known for popularizing his father’s work, painted a number of versions. The art market answering to the call of their clientele ordered additional copies. Some were produced in Brueghel the Younger’s workshop, and others painted by known and anonymous artists. The paintings, though appearing similar, have noticeable differences; sometimes a figure or group of figures is added or omitted, other times specific points are emphasized or an entire colour scheme has undergone a fundamental change.

At first sight the painting pictured above, attributed to Peter Brueghel the Younger, looks familiar. The stage performance, the religious procession, the circle dance and extended view down the bustling street all appear in Baltens’ painting. Brueghel’s work, however, is mirrored. The stage opening faces to the right, the procession and the dancing couples are now on the right side and the circle dance revolves to the left. And you may have noticed the town’s people, found on the lower right in Baltens’ painting, have vanished altogether. The dancing couples, though mirrored, are notably similar in composition and structure. Just for interest’s sake, let’s compare the scenes. You may wish to peruse the images below; each can be expanded by clicking on the image.

The variations in colour and brightness are obvious. Just as obvious is that, compared to Baltens’ tall, slim musician, Brueghel’s bagpipe player is a stocky, languid individual. Where Baltens’ comparatively younger, lithesome peasant woman lifts her leg with apparent ease, Brueghel’s more than middle-aged woman is considerably cumbersome; her forceful facial expression reveals her physical effort and sheer determination. And the couple, just behind her, are particularly zealous as if the two pairs are competing with each other. The two Brueghels are near copies; I would not be surprised if he, or artists in his workshop, used templates. To my mind Brueghel’s dancers are rough and earthy. Brueghel, no doubt, illustrated these uncouth characters, not to mention the inebriated man sprawled out on the ground, to accommodate the requirements of his non-peasant clientele.

Centre: Peter Brueghel the Younger – A Village Fair (Village festival in Honour of Saint Hubert and Saint Anthony) – Auckland Art Gallery, Toi o Tãmaki, New Zealand – detail

Right: Pieter Brueghel the Younger – Flemish Kermis – Alte Galerie Schloss Eggenberg Universalmuseum Joanneum – detail

On The Web Gallery of Art, I discovered another version attributed to Peeter Baltens, titled The Feast of St George with Theatre and Procession. In setting and composition it mirrors the Rijksmuseum version and as such comparable to the Pieter Brueghel the Younger versions. The question arises why would Baltens paint a mirrored, undated, version of his original painting? Possibly a patron requested the painting be adapted to fit in with his interior design, or equally possible that this work is not by Peeter Baltens. Nonetheless it is compelling to compare this work with that of Brueghel the Younger.

In the images shown below, the dance movements of the Farandole are basically interchangeable, although you could argue that some paintings are more successful in establishing the dancer’s forward momentum than others. Where in the Rijksmuseum version, a young girl completes the line, these examples all have a stout woman either being pulled forward or running towards the line to join in; in ‘Baltens’ version the wind has caught her skirt, exposing her naked leg. In the Rijksmuseum painting, the accompanying drummer stands in plain sight. He looks a little bored, but his expression is clearly visible. In the other paintings the musicians — often two players — turn their backs to the onlooker; except, the hurdy gurdy player, in Flemish Kermis, who faces the dancers. Noteworthy to mention that in the vicinity of the dancers, various objectionable activities take place; excessive drinking, gambling, and fighting, to mention but a few.

Centre: Pieter Brueghel II- La Kermesse villageoise avec un théâtre et une procession – Musée Calvet, Avignon – detail

Right: Pieter Brueghel II – Flemish Kermis – Alte Galerie Schloss Eggenberg Universalmuseum Joanneum – detail.

The painting’s most stunning dissimilarity is to be found during the stage performance; one subtle change inviting the spectator to re-evaluate the artist’s intentions. To recapitulate; Baltens painted the husband returning home to find his wife caressing a priest. This could be none other than a critical sneer, especially when you consider that The Reformation was ongoing and that The Low Countries was torn between Protestantism and Catholicism. Most other versions, including the Pieter Brueghel the Younger, shown below, have eliminated the priest, introducing an amorous chap wearing a feather in his cap. A feather could indicate a fighting man, but in this case, more likely to symbolize a freebooter, taking advantage of a given opportunity. The woman, finding herself in a most uncomfortable position, reaches out to the audience, conceivably expressing that all is not well.

The Flemish Kermis, an engaging art genre originating from The Low Countries, never fails to offer social and political commentary. The panoramic view, the bird’s eye perspective and the multitude of diverse figures, make each painting fascinating to explore.

* All the images can be enlarged – click on image to expand

**Left: Pieter van der Borcht – Peasant Kermis – etching & engraving – 1559 – Metropolitan Museum of Arts, New York

Centre: Bruegel the Elder – Kermis of St. George – engraver, Johannes or Lucas Doetechum – c. 1559 – Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Right: Bruegel the Elder – Kermis at Hoboken – engraving, Frans Hogenberg – 1559-1561 – Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam