The name Pieter Bruegel conjures up visions of bulky, amiable peasants dancing, drinking, and generally making merry. Pieter Bruegel the Elder (c. 1525 – 1569) sometimes, referred to as Peasant Bruegel, painted iconic images of dancing peasants in the 16th century. He, as no other artist, showcased the peasant in his rural surroundings. Pieter Bruegel, who chose to spell his name without the letter ‘h’, was the founder of the Bruegel/Brueghel dynasty. Both his sons, Pieter Brueghel and Jan Brueghel, followed in his footsteps, becoming acclaimed artists in their own right. Bruegel the elder, known for his drawings, engravings, and paintings, inspired his peers and generations of subsequent artists. But why did Bruegel, at a time when artists primarily painted portraits or religious paintings, chose to portray the ordinary man, the peasant? And who were his artistic predecessors?

Bruegel the Elder lived in unsettling times. Without examining the historical background of the Bruegel’s era, it suffices to note that Martin Luther posted his ninety-five theses in 1517, the reformation was ongoing, Protestants were being persecuted, Christian Humanism became accepted, and that violent iconoclasm took place in both Germany and The Low Countries. With these social, political, and religious changes, the demand for religious paintings diminished. Churches, in a significant part of the Low Countries, no longer commissioned religious art works. A new art patron arose. The transformed art market requested portraits, landscapes, and genre scenes. In this world of radical change, the theme of peasants and peasant life became popular. Around 1500 the peasant image gradually emerged in art works. The earliest works appeared in Renaissance Nuremberg, the home of Albrecht Dürer. Allow me to present a brief overview of those artists who inspired Pieter Bruegel the Elder and his contemporaries.

The engraving of the dancing couple by Nuremberg’s master artist Albrecht Dürer is, if we disregard the peasant imagery decorating the margins of illuminated manuscripts, one of the earliest images of dancing peasants. This small engraving presents a frolicsome couple dancing. These peasants are plump, unrefined, and earthbound. These lively figures or figures remarkably similar appear in many of the subsequent dance images created by Dürer’s successors and henceforth incorporated into the Flemish School. The bagpiper, instrumentalist of the peasant folk, invariably accompanies the dancers; his image appears repeatedly in the many artworks concerned with wedding dances, peasant festivals, and the ever popular kermis; all three favoured subjects by artists in Germany and The Low Countries.

Peasant Couple Dancing – 1514 – engraving – 11.8 cm x 7.5 cm

The Bagpiper – 1514 – engraving – 12.2 cm x 8 cm

Metropolitan Museum of Arts, New York

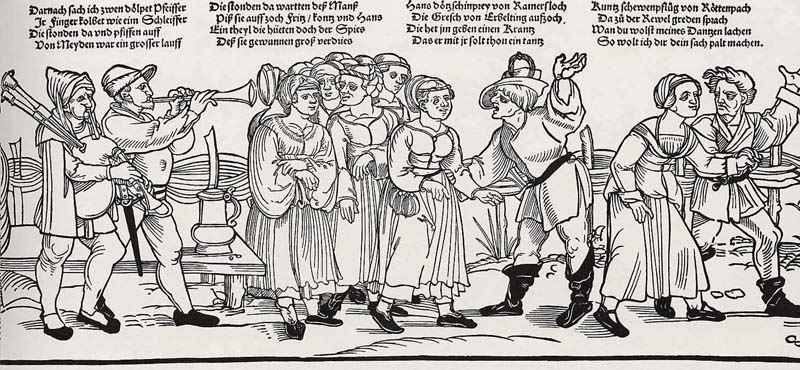

Barthel Beham or his more renowned brother, Sebald Beham, once apprentice to Albrecht Dürer, designed Kermis at Mögeldorf. This long woodcut is composed as a frieze. The narrative opens with a tavern scene, full of drinking peasants followed by two musicians, one playing the shawm and the other bagpipes. In front of them are fifteen peasant couples dancing side by side along the entire length of the horizontal banner. Above each individual section, verses, written by Hans Sachs Nuremberg’s leading poet, scrutinize and comment on the activities taking place below. The dancing figures are rendered in simple outlines, performing walking steps, kicking their legs in the air, and kissing each other, as they progress forwards in what may be a processional.

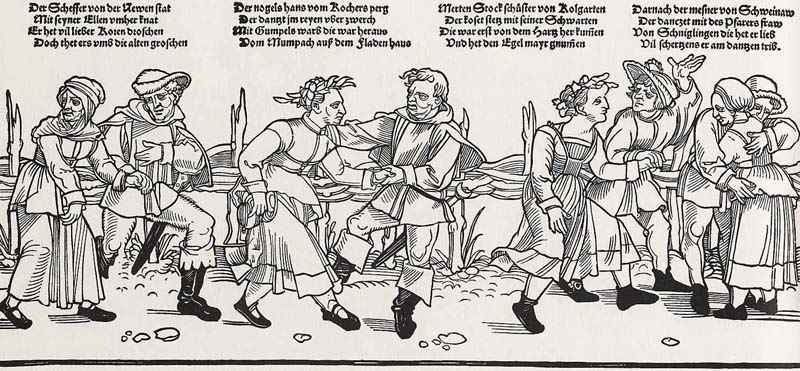

The following merry festive scene is the left section, the dance section, of a larger woodcut by the miniaturist and engraver Sebald Beham. As in the Kermis at Mögeldorf frieze the peasants are revelling, drinking, and dancing. One of the revellers is seen vomiting in the foreground; excessive drinking no doubt being the cause. The dancers are arranged in a semi-circular pattern, accompanied by the typical peasant musicians, a shawm, and bagpipe player. Each couple assumes a characteristic pose. The couple, centre front, prance forward with uplifted arms, another couple faces each other in near embrace, and moving along the circle there is a couple turned back to back. Their arms reach decidedly outwards and upwards. This distinctive pose not only echo Dürer’s famous engraving, but will, a few decades later, appear in the work of Bruegel and his contemporaries.

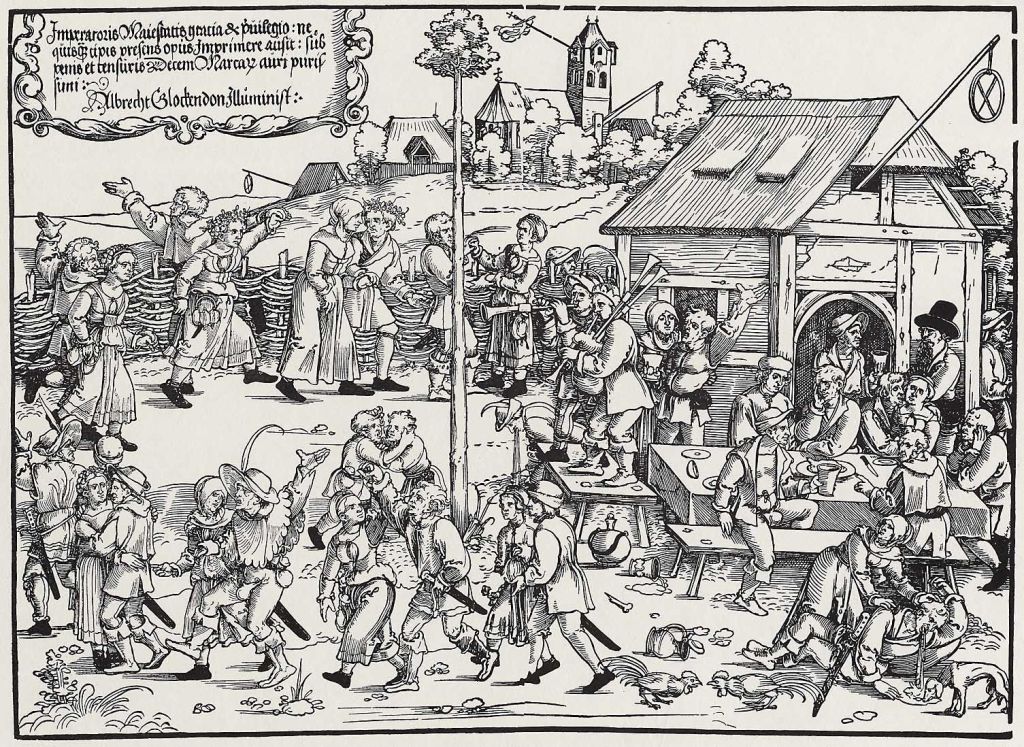

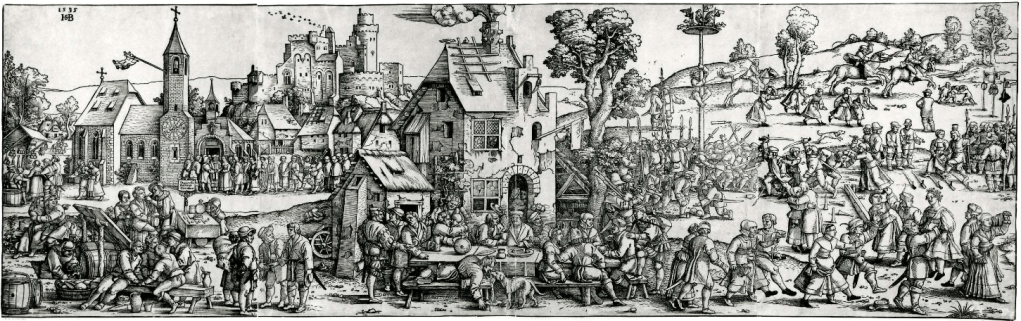

Treat yourself to a panorama view of a village fair; if you take a moment to expand the image of Village Fair (Large Kermis) Sebald Bedam’s exceptional woodcut will astound you. From our high vantage point we are witness to a wedding procession, a merchant selling his ware, barrels of beer, a dentist about to extract a tooth, and a couple kissing in the doorway of the tavern. And in the very centre of the woodcut there is a vomiting man; a dog, just as in Peasant Feast, helps to tidy up the mess. The narrative continues on the right side with fighting men, horses galloping, someone climbing up the maypole, and important to this post, a group of dancing peasants. Two musicians, a bagpiper, and a fellow playing the shawm, lean against the tree. Each dancing couple, now depicted in more considerable detail than in Peasant Feast, have a distinctive shape. Some dance side by side, another is in the process of turning, others are skipping or hopping forward, and the most unusual, one of the girls is being lifted into the air. She, unlike the other women, does not wear a cap, but a tiara of flowers. Is she a bride? Are these dancers celebrating the wedding taking place in the church scene?

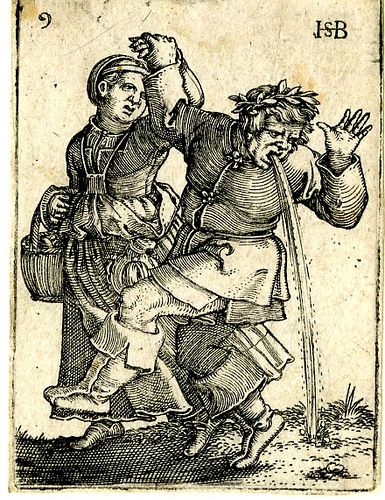

The Peasant Dance (1537) is a set of twelve miniatures depicting dancers, musicians, and illustrates the consequences following a day of unlimited feasting. The dancers, as the examples below show, are stout, rowdy peasants that shift, swing, and turn ponderously. Their heavy clothes and bulky footwear make light-footed dancing an unachievable challenge. The left miniature is no doubt familiar; a direct echo of Dürer’s work. You will recall, Sebald Beham used a similar image in Peasant Feast. In another set of miniatures, The Peasant Feast or the Twelve Months, this image and others reappear, often as near copies. The centre image showing a couple facing each other is common to the work of Sebald Beham, his brother Barthel Beham, their companion Erhard Schön, as well as in the work of Pieter Breugel the Elder and his contemporaries. I have also included a more distasteful image, not unusual in depictions of peasant life and peasant festivals. The vomiting man underscores how the new art patrons amused themselves, relishing in the more unsavoury aspects of, ostensibly, the peasant way of life; in fact vomiting, urinating, and defecating were sought-after, hilarious features poking fun at the hardworking, fun-loving peasant. Or alternatively, these prints and paintings had a moralistic goal, preaching about the excesses of lust, gluttony, and drunkenness.

At this stage, you may be wondering how Pieter Bruegel and his contemporaries (Pieter Balten, Hans Bol, Martin van Cleve, Gillis Mostaert among others) became acquainted with the dance images produced by their more southern neighbours. It is very likely that the images were spread by the sale of prints. Prints were the least expensive form of illustration, sold at art markets and also at local markets which were frequented by salesmen, travellers, and the rising middle classes. Artists, moreover, were known to travel far and wide. Albrecht Dürer, for example, travelled to The Low Countries, stopping over in Antwerp for nearly a year. There, Dürer met Lucas van Leyden, artist of the triptych The Dance around the Golden Calf, and the artists exchanged prints. Bruegel the Elder travelled to Rome, no doubt, to use a modern term, networking all the way. And as a well-informed humanist Bruegel was interested in the peasant way of life; according to the early 17th century art historian Karel van Mander, Bruegel, disguised as a peasant, attended rural festivities uninvited.

Around ten years before Breugel the Elder painted his famous dancing peasants, a fellow artist from Antwerp, Frans Huys (1522-1562) engraved The Lute Player/ Master Jan Slechthoofd; part of a series of Allegorical Scenes of Flemish Proverbs Concerning Sloth. The work, possibly after Hieronymus Bosch or Cornelis Massijs, is unusually interesting from a dance point of view, having a row of four familiar dancing couples accompanied by two typical musicians as decoration for the mantelpiece. Frans Huys, worked for the most influential publisher in Antwerp, Hieronymus Cock, who, incidentally, was also the employer of a many young artists including Pieter Balten, Pieter van der Borcht, and Pieter Bruegel. It is evident that by the mid 16th century, Beham’s dance images were well known in Flanders.

And then there is the drinking jug! Peasants who enjoyed drinking large quantities of ale were never lacking at weddings, festivals, or at the annual kermis. Jugs were the ideal vessel. Many of these stoneware jugs were produced in Raeren, a small town not far from Liège, famed for its pottery production. These beautifully decorated jugs, a type of 16th century tubberware, were immensely popular in The Low Countries. The jugs were frequently embellished with the peasant dancing images we have come to know from Sebald Beham. The familiar couples hopped, turned, and capered. Even the puking man makes an appearance.

Right: Raeren Jug – workshop Jan Emens Mennicken – 1576 – British Museum

The peasant theme, in genre painting, took a firm hold in the second half of the 16th century. Pieter Aersten’s Egg Dance (1552) radically places the peasant and peasant life as the main subject of the painting. A less obvious message, however, lingers in the background. Progressive as he was, Aertsen seemed suspended between the old and the new worlds, interweaving a religious undertone into his work. Bruegel the Elder and his contemporaries established the peasant genre with their wedding celebrations, holiday feasts, kermis, and tavern scenes. Religion still played a role, though the biblical implication was frequently intertwined with the moral connotations. Even The Peasant Dance, Bruegel the Elder’s vibrant painting, presenting a feast of drinking and dancing, is full of symbolism. The broken handle of the jug, the small illustration of Maria pinned to the tree, the fool in red and yellow attire standing precisely in line with the dancers, and the bagpiper, are but a few of the symbols that reveal and imply a moralising tone.

The Peasant Dance was groundbreaking; instead of the customary bird’s eye perspective, Bruegel places his viewer on the same plane as the action. Just as innovative are the large figures literally ‘running into the painting‘. Bruegel the trailblazer rejuvenated Sebald Beham’s dancing figures. A close look at The Peasant Dance reveals the familiar dancing couples. Beham’s straightforward forms have transformed into fully fledged figures, but the characteristic dance movements are distinctly present. And no one can miss the large ale jug resting on the somewhat tipsy peasant’s lap.

Alison G. Stewart has written an excellent study about the origins of peasant festival imagery. Many dance images are discussed in detail.

Before Bruegel: Sebald Beham and the Origins of Peasant Festival Imagery /Alison G. Stewart 2008 – ISBN 978-0-7546-3308-2