The Spanish dancer inflames the senses. Her splendid carriage, her vibrant footwork, her profound emotion, her articulate hand gestures, and her powerful and expressive arm movements are irresistible. Many Dutch artists have fallen under her captivating spell. Kees van Dongen, Jan Sluijters, Piet van der Hem, Leo Gestel, and Kees Maks travelled to Spain in the early years of the 20th century. All were mesmerized by the Spanish beauty. This post explores images of the Spanish dancer in the first half of the 20th century with just a glimpse into the present day.

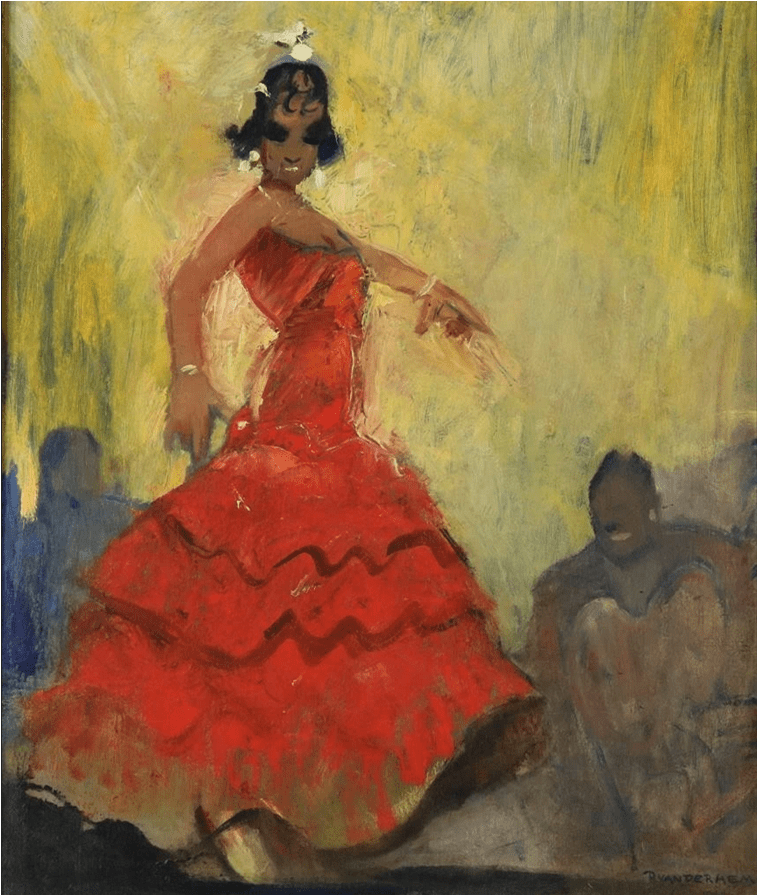

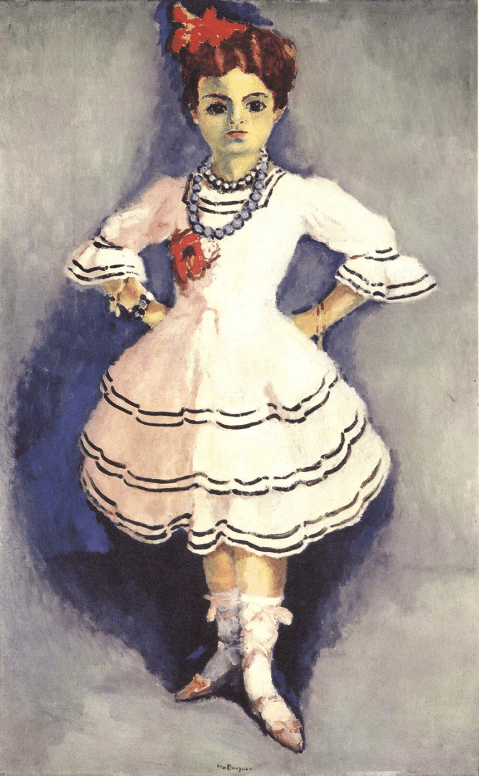

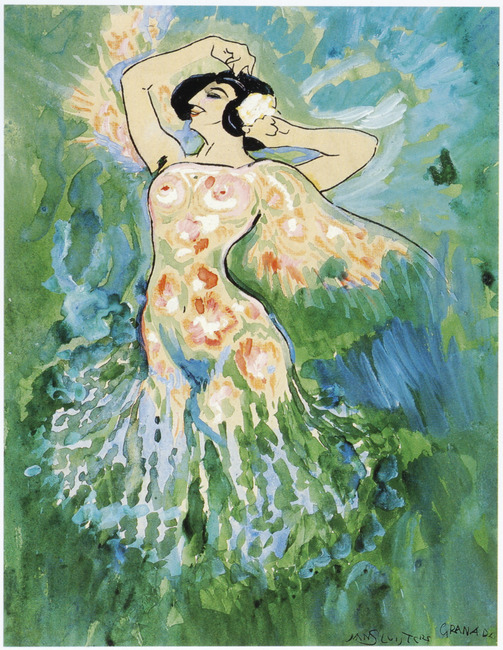

To start with, I have selected three diversely stunning portraits. The first, by Piet van der Hem who studied in Spain in 1913-14; although his provocative painting is not dated it most probably springs from his Spanish years. Next, a portrait of a young Spanish dancer by Kees van Dongen, who visited Spain in 1910-11. In contrast to some of van Dongen’s other dance images, this commanding young lady does not actually dance. Her stance and her demeanour, however, are unquestionably that of a dancer. As a point of interest, this lovely dancer has dark almond shaped eyes, a feature so characteristic to van Dongen female figures. And finally, Jan Sluijters magnificent sensual dancer created during a stay in Granada in 1906.

Centre: Kees van Dongen – Danseuse espagnole – 1912 – 93 x 150 cm, oil on canvas – Musée Fabre – Montpellier

Right: Jan Sluijters – Spanish Dancer – c. 1906 – whereabouts unknown – RKD

The vibrant dancer pictured in Piet van der Hem’s Flamenco Dancer dominates the stage. Her buoyant red dress demands attention. And if that is not sufficient, she confronts her every onlooker with a passion and self-confidence that allows no one to escape. Take note of her defiant twisted shoulders, her forceful hand gestures, her powerful arms; this lady steals the show. Less colourful, but no less tantalizing, is the image of the striking dancer pictured below. In this watercolour, painted whilst van der Hem visited Madrid in 1914, the dancer is performing on a platform stage, a tablao. At the bottom of the image, you can detect a few men: either musicians or members of the audience. They are painted in muted tones that blend in harmoniously with a dark panel immediately in front of them. Van der Hem toys with light and shadows; the faint silhouettes of the musicians sitting on the stage are practically absorbed by the light. This similar yellowish light encompasses the dancer; she outshines all the other figures in the composition.

Kees van Dongen’s painting Antonia la Coquinera is named after the dancer herself. The celebrated dancer, la Coquinera, sways from side to side swinging her soft elongated arms harmoniously. Van Dongen’s dancer, contrary to so many other images of a Spanish dancer, neither confronts her audience nor does she appear to be particularly passionate. Rather, la Coquinera dances gently. Her movements are delicate and gracious. Van Dongen has poised her in a soft S-curve; her overly projected hips counteracted by the strong complimentary pull of her torso. This curve is further underlined by the flow of her swirling skirt. She is accompanied by a guitarist, who too, has his eyes cast downwards. And of course, van Dongen, a Fauvist at the time, combined solid planes of dark blue, deep red, and vague pink, all applied with his customary heavy brushstroke.

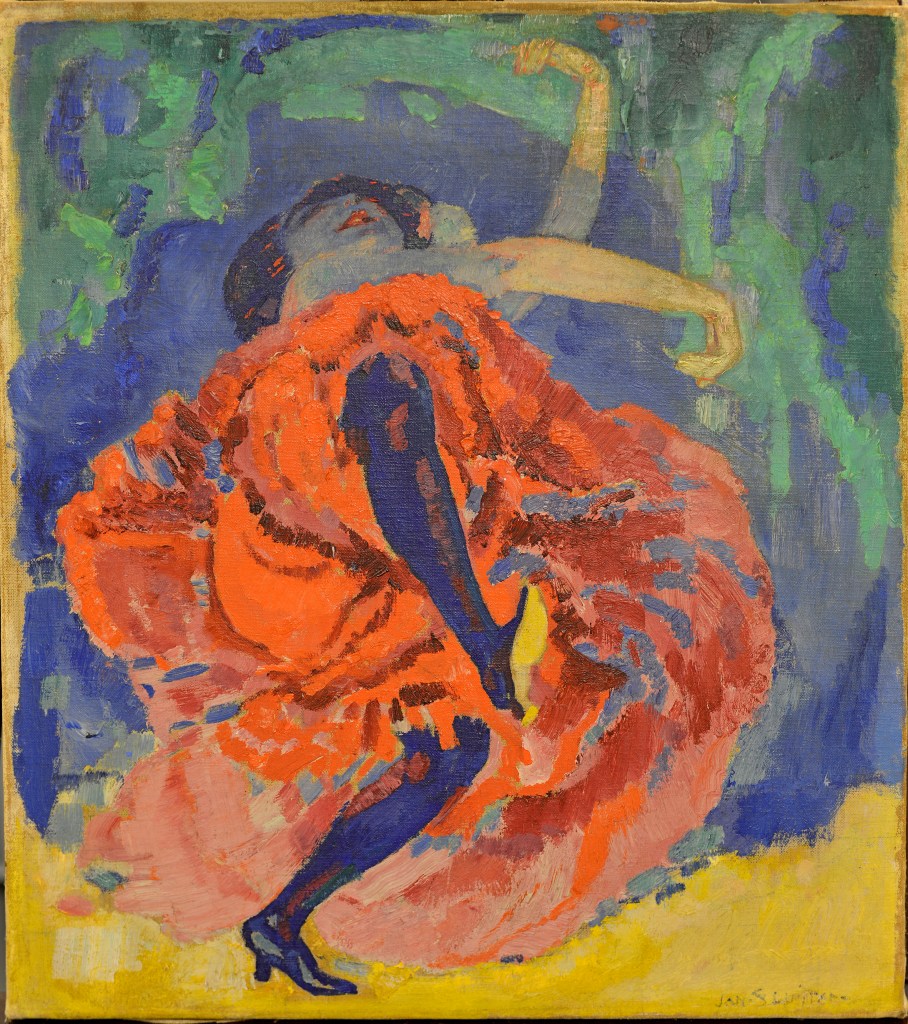

Jan Sluijters travelled to Spain in 1906. Beguiled by the intriguing Spanish performer, he composed numerous studies culminating in two astonishing bold paintings: Spanish Dancer (1906) and Spanish Dancer (c. 1907). Sluijters used a daring colour palette. There is no escaping the stupendous impact of the central red area. This flurry of reddish tones, the dancer’s skirt and bloomers, forms an enormous circle that covers two-thirds of the canvas. A yellow tone, the same as the shoe sole, claims the lower section while the area behind the dancer is blue adorned with irregular strokes of green. The dancer, flaunting her leg kicks, is a stunning mover. Sluijters innately understands the mechanics of body awareness as well as the dynamics of her spirited movement. He has captured her energy, her vivacity, and her passion in a most convincing way.

Spanish Dancer – c. 1907 or perhaps 1909 – oil on canvas,40 x 35 cm – RKD – private collection

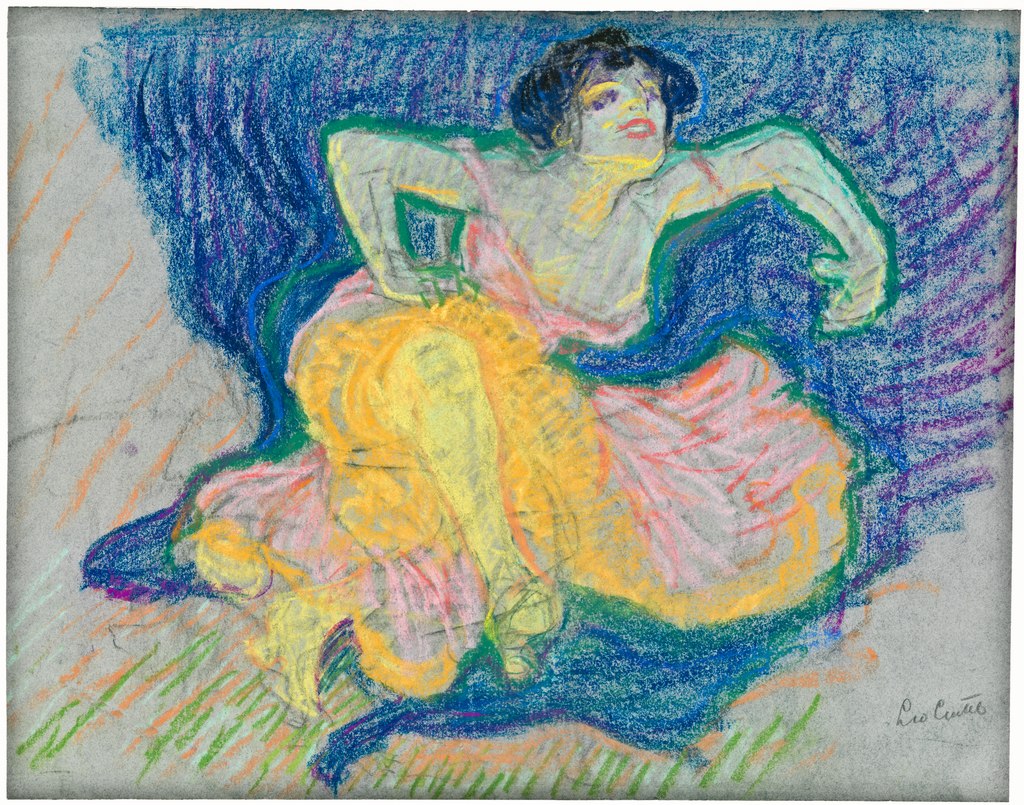

Leo Gestel, one of the leading artists of Dutch modernism, travelled to Spain and Mallorca in 1914. He stayed there for some time evolving his specific style of cubism; this development is best seen in his Mallorca landscape paintings. During this period he also painted figurative works including a number of portraits of Spanish beauties. The drawing Spanish dancer sometimes called Music Hall Dancer was, however, not created during his Spanish period, but inspired by a revue dancer that Gestel saw in Paris.

This dancer definitely makes an impression. Gestel has captured the exact moment when she brazenly projects herself directly towards her audience. There is little refinement in her manner; she is fierce and no doubt temperamental. Her angular arms, her high shoulders and her fiery expression are riveting. I cannot unravel her movement. Gestel has chosen not to include a floor line. Perhaps the dancer is proceeding forward in a crunched position, or possibly moving in a similar fashion to Jan Sluijter’s Spanish Dancer. Sluijters and Gestel were not only peers, but friends. Sluijters, no doubt, influenced Gestel’s work.

Spanish Dancer (also named Music Hall Dancer) – c. 1910 – drawing on blue paper, 32.5 x 41.4 cm – Universitaire Bibliotheken Leiden – RKD

The Spanish dancer, whether portrayed by Sluijters or by Gestel, is an untamed, passionate dancer. The dancers, each in their own specific way, enjoy an undeniable contact with the onlooker. Sluijter’s dancer is prepared to kick anyone approaching the canvas and Gestel’s dancer, no less aggressive, asserts herself dauntlessly.

In both Sluijters’ and Gestel’s image, the dancing figure fills the entire space. The little remaining background area is irregularly coloured in large, non-descriptive rough planes. Whether the artist used oil paint or chalk pastels, the strokes and lines are sketchy and fragmentary. Both artists applied bold colours, splashing with large areas of yellow and blue. The colour combination may not surprise us today, but these artworks were created in the first decade of the 20th century, when society was still accustomed to more subtle colour combinations. Sluijters’ assemblage of clashing colours juxtaposed against black stockings would have been startling. Equivalently, Gestel’s unorthodox colour combination would have raised some eyebrows. It goes without saying that Henri Matisse and other members of the Fauvist movement influenced the work of the Dutch painters. Notwithstanding, Paris, home to the avant-garde, had more to offer. Kees van Dongen, a fervent Fauvist, attended a performance of Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, resulting in a vivid painting of the ballet Cléopâtra. Although there is no documentation to report if Sluijters or Gestel ever attended a ballet performance they could not have avoided noticing posters of Bakst’s designs on the Parisian billboards. Bakst’s use of colour, as that of Henri Matisse, was revolutionary.

Kees Maks painted images of the circus, revues, cabarets, and a variety of dancers with a particular fondness for Spanish dancers. Although he visited Madrid in 1903-4, he typically sought his inspiration in the visiting Spanish dancers who appeared in theatres and cinema. He frequently invited these entertainers to his studio. There, he reproduced a theatrical setting using spotlights and other artificial light effects. He was enchanted by the visiting Spanish dancer Sotomayor; painting her and her troupe a number of times. The sphere of the large-scale painting, Dance Feast with Sotomayer, is effervescent; Sotomayer is vivacious and smiles unhesitatingly. The background figures, in this posed composition, are just as frolicsome. I recently saw this painting at the Singer Museum, and apart from the sheer impact of its overwhelming size, I found the dancer’s expression absolutely irresistible; almost an invitation to join in with the festivities. I also seized the opportunity to take a closer look at Maks’ application of paint. The skirt consists of small square patches with the paint, for want of a better word, plastered onto the canvas.

Dance Feast with Sotomayor – c. 1927 – Oil on canvas, 158 x 230 cm – Nardic Collection – Singer Museum, Laren

There is one artist I must not forget; Willy Sluiter (1973-1949). Sluiter worked primarily in the Netherlands, never travelling to Spain. He was an acclaimed artist who, besides painting many seaside villages, was a prominent illustrator of posters, advertisements and political prints. Apart from two delightful dance images, one of fisher folk dancing at a local fair and the other a humorous fisherman from Volendam, Sluiter painted a full-length portrait of a Spanish dancer. Carmen, a larger than life-size painting, features a cheerful flamenco dancer performing with castanets. This gracious, well-shaped dancer is represented by means of a long diagonal line. Starting from her gently extended foot, the long diagonal continues, bypassing a slight twist of her torso, up to her partially averted head. En route the texture of her dress skilfully changes from a smooth, polished, satin, to a patterned weave complete with a fringe before progressing to yet another soft satin. In contrast to any other painter mentioned in this post Sluiter has adopted a more traditional painting style displaying his ability to paint a variety of surfaces. This also applies to the background. The various shades of yellow blends harmoniously, giving the impression that the eye-catching lady is performing on a sunlit stage.

Carmen – 1915 – 250 x 175 cm, oil on canvas – RKD – Christie’s

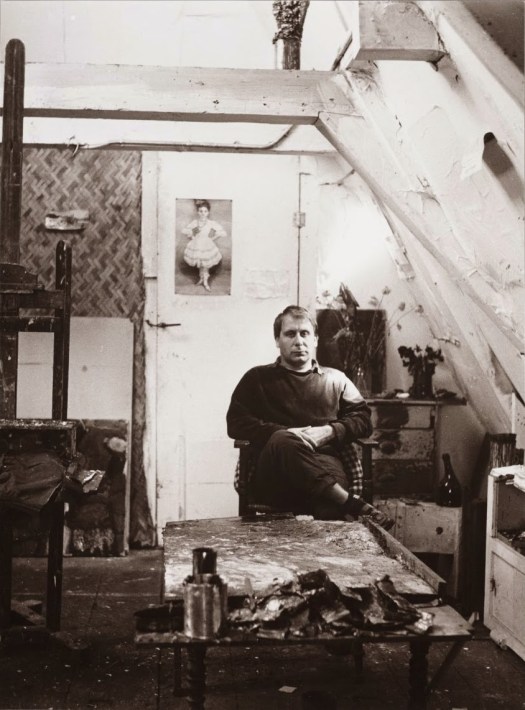

Spanish dancers offer a continual source of inspiration. Jan Sierhuis (1928-2018), a contemporary artist and a flamenco aficionado painted and sculpted flamenco dancers and musicians for more than three decades. Albert Groenheyde (1939), known for his realistic and not necessarily flattering close-up portraits, has created an entire series of stunning flamenco musicians and dancers. Likewise, Gerard Staals (1946) in his Fiesta Gitana series captures the dynamic and emotional impact of the gypsy flamenco in ravishing warm colours. Much softer, even tender, are the full-length flamenco portraits by Pieter Smit. The irresistible force of the Spanish dancer is everlasting.

One last thought; inspiration has an intriguing way of meandering. This photograph of Jan Sierhuis was taken in 1961. You will have noticed a poster reproduction of Kees van Dongen’s Danseuse espagnole on the door.