Anna Pavlova was a superstar. The legendary Russian ballerina presented her art in every corner of the world, dancing not only in all the major capitals, but also in a multitude of smaller theaters, delighting countless audiences and inspiring many young dancers. The Dying Swan, a short solo created by choreographer Michael Fokine was her signature piece. Pavlova and The Swan became synonymous.

Pavlova captured the fascination of photographers, painters, sculptors, poets, film directors, as well as the commercial world of advertising. She was the most photographed woman of her time, both on stage and off. Anna Pavlova became a household name; she was the world’s greatest ballerina. A tulip was once named after Pavlova. And a delicious meringue based desert is named Pavlova. Igor Carl Fabergé designed crystal wine glasses displaying an image of Pavlova in the stem. There is a Pavlova perfume, Pavlova statuettes, a crystal Swarovski figurine, Pavlova shoes, and postage stamps among the merchandise that carry images of the extraordinary ballerina. Meters of books have been written about her. During her lifetime and after her untimely death in The Hague, 1931, artists world-wide were and are inspired by her genius and artistry. Kees van Dongen was the first Dutch artist to fall under her spell.

The date is 1909. Paris was mesmerized by the Diaghilev Ballets Russes. Cléopâtre, an oriental spectacle choreographed by Michael Fokine, took the French capital by storm. The ballet tells the tale of two lovers. Ta-Hor, danced by Anna Pavlova, finds her beloved Amoun dead after spending a sensuous night with Cléopâtre. Ta-Hor is devastated. And that is the very moment Kees van Dongen captures. Ta-Hor, totally distraught, extends her arms dramatically outward, stretching her elongated neck as far back as possible. We cannot see the features of her face, but every gesture of her fragile body utters agony. Reclining languidly behind her is seductive Cléopâtre, impervious to Ta-Hor’s anguish. Van Dongen has painted his personal recollection, a souvenir as the title enlightens, of an irresistible performance.

Pavlova, in all probability, never saw this painting. Van Dongen never met Pavlova. He definitely was not part of Diaghilev’s inner circle. Would Pavlova have appreciated the painting? Victor Dandré, Pavlova’s manager and possibly her husband, writes that Pavlova invariably sought a good likeness, a dedicated impression of her artistry and that the artist conveys her expressiveness. Van Dongen’s impression is without doubt zealous, and most definitely expressive, but in no way resembles the photogenic Pavlova. Whether the following two works, painted by Dutch artists working in the Netherlands, met her wishes is unlikely. Both paintings were executed during her lifetime, but as with Van Dongen’s work, probably not seen by her. Willem de Zwart and Herman Bieling have pursued an individualistic approach.

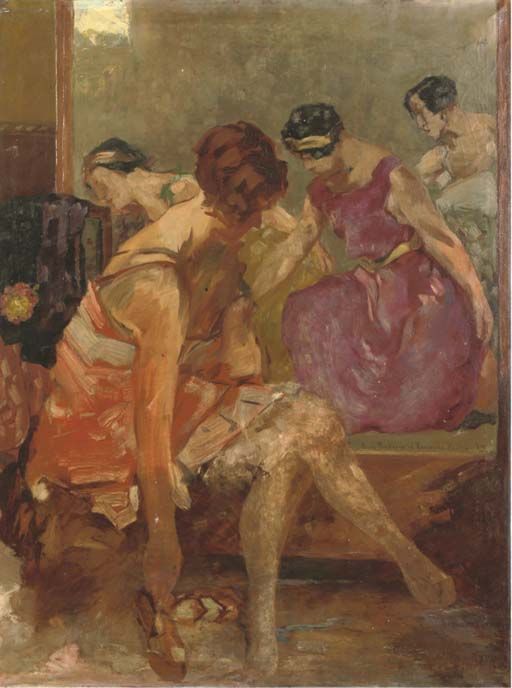

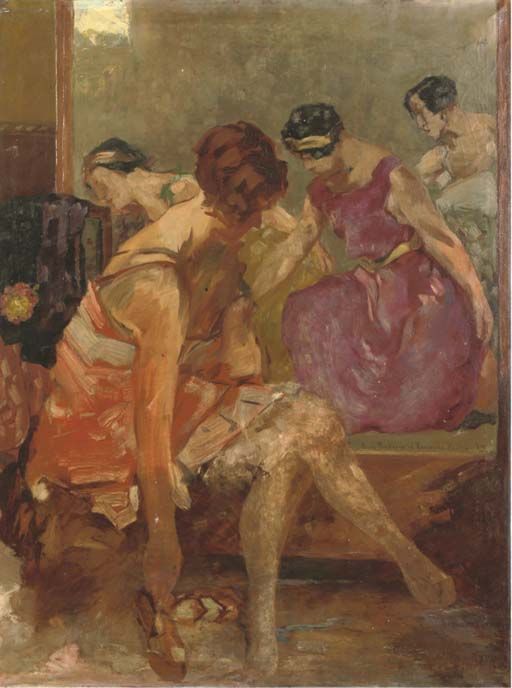

In 1885, Willem de Zwart (1862-1931) painted two works illustrating ballerinas, but he was primarily known for his village scenes, animals and town views. The 1927 painting, shown above, presents dancers during a rehearsal, while the ballerina, Anna Pavlova, rests or adjusts her shoes. Behind her, visible through the mirror, other dancers are shown rehearsing. This unusual composition, where only the dancers reflected in the mirror offer the slightest hint as to the dance quality or movements, makes one wonder why the painting is decidedly linked to Anna Pavlova. Curiosity got the better of me. Perusing though many photographs hoping to discover a tangible clue, I found a photograph of Autumn Leaves, a choreography by Anna Pavlova, where the dancers wear floating chiffon-like dresses complemented with belts or sashes, arrange their hair in a shortish style and perform subtle curves and inclinations. Perhaps, bearing in mind the warm colours used by the artist, Willem de Zwart had Autumn Leaves in mind. *

More enigmatic is the portrait of an apparently young dancer sitting woefully. Her voluminous white skirt covers the chair entirely. A small mirror, or possibly a window, presents a partial back view of another dancer. Most peculiar is the absolutely incorrect way that the dancer has tied her ribbons. This type of lacing demonstrates more affinity with gladiator scandals than with pointe-shoes.

Herman Bieling, (1887-1964) was the founder and driving force behind the artistic group De Branding. Bieling, an artist of the avant-garde, was enthralled by the theatrical, designing theatre sets, painting cabaret performers, dancers, and circus artists. These paintings are generally brightly coloured, dynamic, painted in his specific blend of cubism fused with expressionism. His interpretation of Anna Pavlova, in contrast, is a figurative work using a minimum of colours. Anna Pavlova, whose photographs graced so many books and newspapers, cannot be discerned from this painting. Pavlova did not sit for Bieling. It is possible that Bieling was inspired by a photograph. If so, a portrait by the Viennese photographer Madame d’Ora (Dora Kallmus), though only vaguely similar to the painting possesses a comparable composition and, even more notable, the same melancholic sphere.

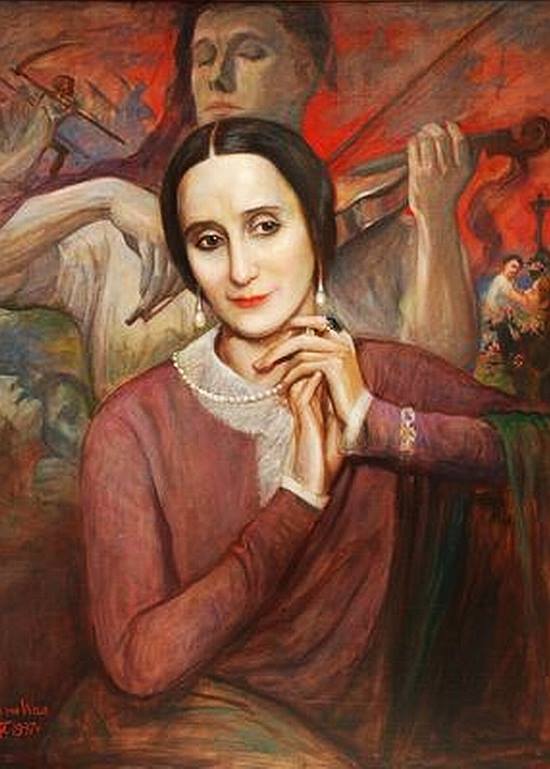

The charismatic Antoon van Welie (1866-1956) was an exceptionally successful artist, painting, in his heyday, the most prominent personalities of his time; Isadora Duncan, Sarah Bernhardt, three different Popes and Mussolini were amongst his clientele. Van Welie composed two paintings of Anna Pavlova, both posthumously; a half-portrait and a full length painting of Pavlova dancing her most famous solo, The Dying Swan.

That Antoon van Welie based his portrait, shown below, on a photograph is evident. The German photographer, Carry Hess, was known for her portraits, nudes, fashion and photographed various dancers, including Mary Wigmann, Niddy Impekoven, and Anna Pavlova. Van Welie’s portrait is a faithful recreation of the black and white photograph, but where Hess places Pavlova in a neutral background, Van Welie designs a symbolic world. Behind Pavlova, the artist, at one time strongly influenced by symbolism, introduces a scene of diverse figures, the most prominent being the violist towering over Pavlova. This figure, always portrayed with his eyes closed, appears in a number of Van Welie’s works. Less prominent, secluded in the background, are the two lovers, the fighting men carrying spears, the two men roaming amongst blossoming flowers and the crucifixion, all of which inhabit a haunting red backdrop. Van Welie was an intense artist; I dare say that the background reflects on both Pavlova and Van Welie; Pavlova’s separation from her beloved Russia and Van Welie’s devotion to his partner Bob Koelemeij.

A year after painting Pavlova’s portrait, Antoon van Welie executed a full length image of the ballerina in her legendary role, The Dying Swan. This is a short solo, to music by Camile Saint-Säens, and not to be confused with the full-length ballet Swan Lake. Pavlova is poised near a stream, dressed in her traditional swan costume. Sorrowfully, she looks down at the glistering water. As she delicately reaches towards the brook a friendly swan, perhaps symbolizing her pet swan Jack, approaches her. The ballerina is encircled by undulating hills, in a moderately green yet conspicuously autumn-like landscape. Near her are two miniature Grecian figures; possibly muses. They support a fountain surrounded by scrubs bearing red berries. Are these poisonous yew berries? A symbol of Pavlova’s passing?

Van Welie’s portrayal of Pavlova in her swan costume would invite immediate recognition. Photographs of Anna Pavlova frequently appeared in newspapers and magazines. Even though the majority of people would not have had the opportunity of seeing her dance on stage, Anna Pavlova would have been familiar to most everyone.

Sixty years after her death, Ine Veen, ballerina, actress, turned artist and Jean Thomassen, writer and artist, rekindled the Pavlova legacy in The Netherlands. They created drawings and paintings inspired by historic photographs. Spellbound by Pavlova’s magnetism they set out to research and collect memorabilia in preparation for a Pavlova exhibition held to commemorate her death. Their research took them to Ivy House, once Pavlova’s residence in London. In 1991 the exhibition was hosted in Hotel Des Indes, the hotel in The Hague where Pavlova passed away.

The contemporary artist, Jean Thomassen, has a unique style which is referred to as Absurd Reality. His world is realistic, admittedly an odd form of realism, congested with a profusion of details which are rationally out of place though fathomable. His portrait of Anna Pavlova, inspired by a photograph, contains little of his usual characteristic style, though his comprehensive eye for detail is obvious. The beautiful satin dress, the dainty shoe, the delicate lace, and the plumage of the fan are all precisely rendered. Thomassen has added a few details of his own. In the background Ivy House can be seen, and Thomassen has placed a little bird on a branch, which he explains, represents a gift presented to Pavlova when she visited India. And there is, like in all Thomassen’s work, a bizarre detail; on the brick construction, small but visible is a rat named Mickey; apparently a frequent visitor at the artist’s studio.**

Equally eye-catching are Veen’s three-dimensional works, based on well-known photographs, where she uses a variety of material including gold leaf, gemstones, sparkles, and in the case of Anna Pavlova, The Dying Swan real tulle and feathers. In another version of the same image, the finishing pose of the legendary solo, Pavlova rests against a dark blue background furbished with a splash of red. Her white tutu is cracked by two ragged lines.

Pavlova sat for distinguished artists including Sir John Lavery, Ernst Oppler, Valentin Serov, Savely Sorin and the magnificent sculpture Malvina Hoffman. She did not pose for any of the artists mentioned in this post. Most of these artists gathered their information and inspiration from existing photographs, newspaper clippings and memorabilia. Artists worldwide, to this very day, are still inspired by the legendary Pavlova. Hilda Butsova, dancer with the Pavlova Company perceptively explains the magic of Pavlova in an interview published in Dance Magazine, November 1972.

‘No other single being did more for ballet than she. Her genius was intangible as the legacy she left behind. What remains of Pavlova today is not a movement in art, not a tendency, not even a series of dances. It is something far less concrete, but possibly far more valuable: inspiration’

*This painting, sold at Christie’s in 2006, titled Anna Pawlovna of the Russian ballet: ballerina’s is inscribed, lower right, with the title. Even after expanding the image, I am still unable to confidently decipher the minuscule letters. Just for the record, Pavlova’s name here is incorrectly spelt. This was not totally uncommon. King William II of the Netherlands was married to Anna Pavlovna of Russia (1795-1865) and the spelling of Anna Pavlova (ballerina) is sometimes confused with the former Dutch queen. Furthermore, the name Pavlova is often also spelt as Pawlowa and sometimes, though less common, as Pawlova.

*This painting, sold at Christie’s in 2006, titled Anna Pawlovna of the Russian ballet: ballerina’s is inscribed, lower right, with the title. Even after expanding the image, I am still unable to confidently decipher the minuscule letters. Just for the record, Pavlova’s name here is incorrectly spelt. This was not totally uncommon. King William II of the Netherlands was married to Anna Pavlovna of Russia (1795-1865) and the spelling of Anna Pavlova (ballerina) is sometimes confused with the former Dutch queen. Furthermore, the name Pavlova is often also spelt as Pawlowa and sometimes, though less common, as Pawlova.

**Jean Thomassen – Anna Pavlova Triomf en tragedie van een mega-ster p.145