Even before Bruegel the Elder painted his famous dancing figures, artists of The Low Countries portrayed couples dancing. These, for the most part, were rowdy peasants enjoying themselves in taverns or at outdoor festivities. The structure and jovial character of the dance required that the revellers dance side by side, or, when facing each other, to maintain sufficient distance to whirl and turn.

In the 19th century, the waltz appeared. Couples now faced each other, and the man actually placed his arm around his partner; couples moved very close towards each other, their bodies touching, to facilitate the rapid turns. The waltz was considered indecent, vulgar. It was an unqualified success. Social dancing changed radically; the closed dance position gained immense popularity and became commonplace. The waltz with partners holding each other shamefully close inspired foreign artists to paint elegant couples waltzing in magnificent venues. Artists of The Low Countries, however, looked elsewhere.

Bergen, once a small coastal village in North Holland, attracted writers, artists, and architects. There, in the early 20th century, an artistic colony evolved, leading to the establishment of the Bergen School. The movement, influenced by expressionism and cubism, was led by the French artist Henri Le Fauconnier and the Dutch artist, Piet van Wijngaerdt. The Bergen School became the first expressionist art movement in The Netherlands, employing angular forms, light and dark contrasts, powerful colours, and broad brushstrokes.

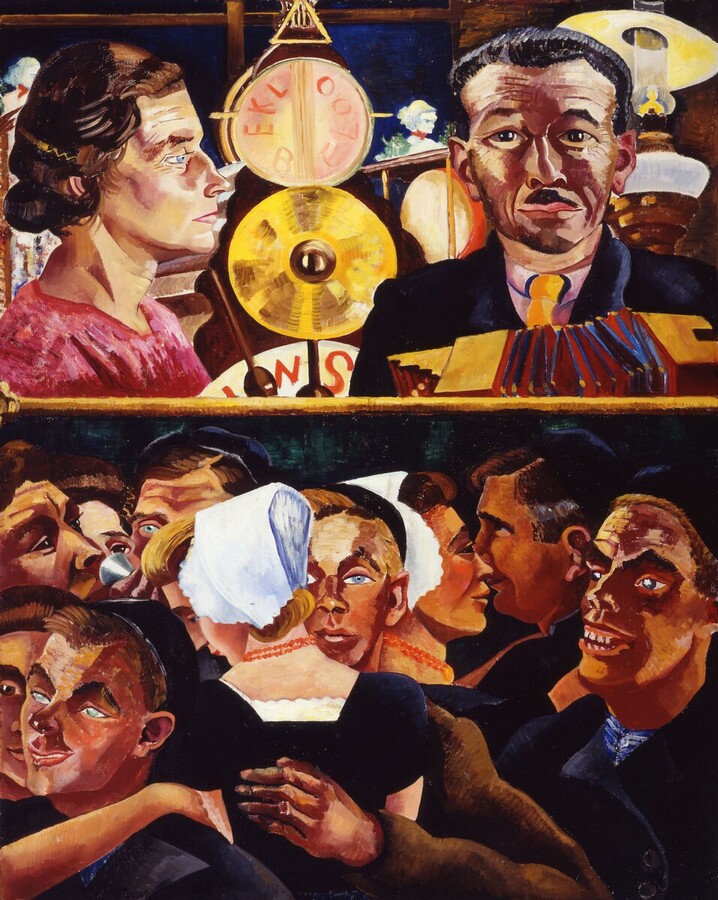

All the characteristics common to the Bergen School are present in this large and multicoloured painting set in a café named De Rustende Jager.* Most likely this is the weekly get-together, out on a Saturday evening, at the local pub. Your attention is instantly drawn to the front couple, and more specifically to the woman clad in her very best white blouse, adorned with a small lace ruff arranged over a larger frill that falls over her shoulders. Her partner, who holds her tenderly, is in contrast to the other guests, stylishly dressed with a white collar, a jacket and perhaps, though I cannot be certain, a tie. They are the centre of attention. Is this just an ordinary Saturday evening dance? Is this well-dressed man, an incidental visitor from a large city, or are we invited to an engagement celebration? Whatever the reason for this festivity you would expect a light-hearted, invigorating sphere, but, the artist, Frans Huysmans (1885-1954) has not painted an especially cheerful couple nor are the other dancing couples particularly frolicsome. Even the pipe-smoking pianist, propped into the left bottom corner, lacks cheeriness.

Compared to the other figures, the expression on the faces of the front couple is reasonably realistic. But their faces, just as the others, are angular, rough, and more chiseled than painted. Likewise, all the figures and most particularly their arms and legs resemble craggy wood carvings, similar to the work of the expressionist movement Die Brücke. All the couples dance intimately without the slightest acknowledgment to the other couples on the floor. The crowded café leaves little space to dance; Huysmans neither illustrates movement nor yields us any clue as to which dance is being performed. Only the partner’s grasp, their body language, which Huysmans beautifully defines giving each couple a unique embrace, reveals each individual’s innermost emotions.

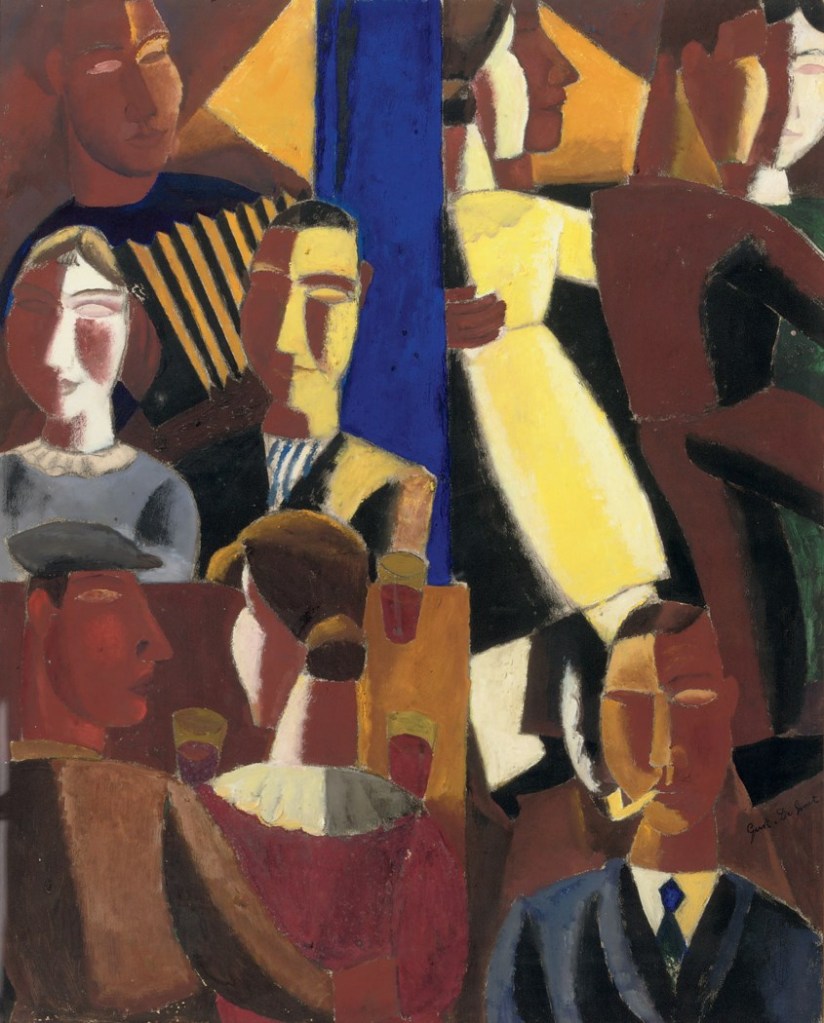

The Flemish artist, Gustave de Smet (1877-1943), fled to The Netherlands at the dawn of World War I, where he became conversant with both German and Dutch expressionism. Given that de Smet, when he lived in The Netherlands, participated in the Bergen School, it is no more than logical to include his artwork The Ballroom in this post.

In the centre of exclusively earthy colours, a blue column divides the painting into two halves. An even closer look reveals not two, but four separate scenes; two couples sitting at a table, an accordionist, a man smoking a pipe, and two dancing couples. Most of the faces stem from primitive artifacts, recalling not only German expressionism, but also the masks that inspired Picasso in various works including ‘Les Demoiselles d’Avignon’. I find the ‘French’ beret, on the left man’s head, a very distinctive touch.

The two dancing couples, accompanied by an accordionist, are compressed in the right half of the painting. The top of their heads has been cropped. Likewise, the man in brown is cropped, as is the woman in yellow. She, together with her partner, is partially obscured by the vertical blue divider. The couples dance cheek to cheek; holding each other in a standard ballroom position, the man clasping the woman snugly around her back. What can we surmise about these figurative doll-like physiques? In the first place, the dance, even though it appears rather wooden, is vivacious; the dancer’s legs are lifted well off the floor. Secondly, the dancing couples, despite their linear simplicity, are animated as well as being affectionate and sociable. The accordionist, too, has a cordial expression, so I assume that he is performing a lively melody. Stark as the painting may initially appear, everybody is actually having a good time.

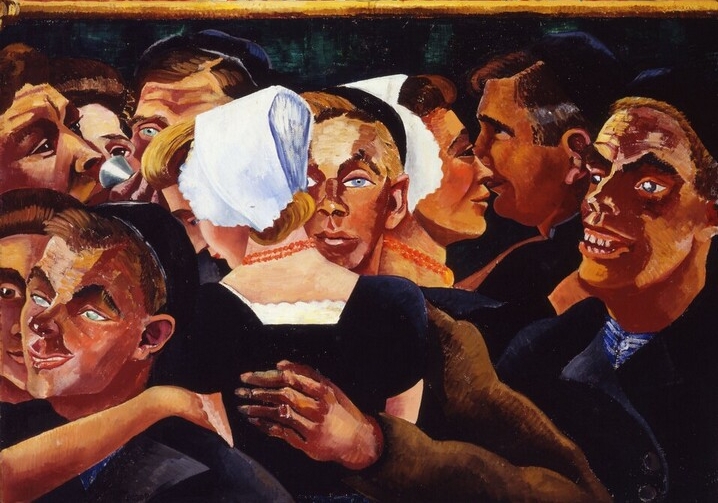

Charley Toorop (1981-1955), known for her forceful, realistic style, was affiliated with the Bergen School. She was a devoted admirer of Vincent van Gogh, choosing to live temporarily in the poverty-stricken mining area, Borinage (Wallonia), where van Gogh had lived and worked. Daughter of the equally acclaimed Art Nouveau artist, Jan Toorop, Charley opted to paint powerful scenes of modest, hard-working people. Among her subjects were farmers, land-workers and village folk, finding inspiration in the coastal town of Domburg, an area where she painted a series of potent works including Musicians and dancing peasants. The painting is divided into two sections; the top showing the musicians and the lower section an impression of a local dance event.

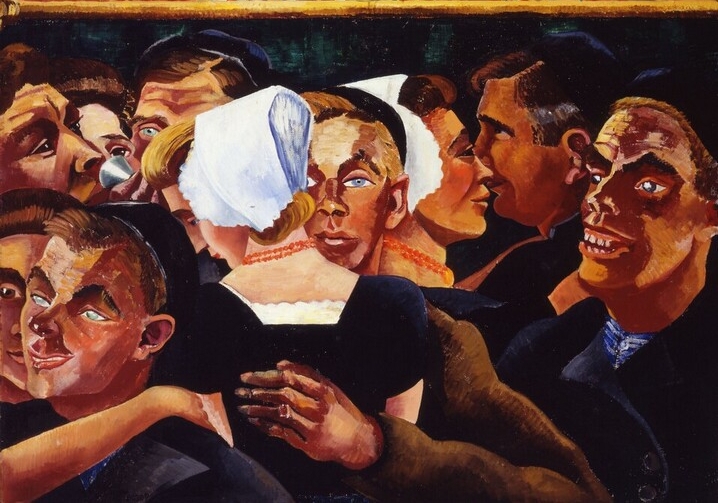

- Left : Musicians and dancing peasants (lower section of the painting)

- Right: Musicians and dancing peasants 1927

- Oil on Canvas – 150,3 x 120,5 cm Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterloo, The Netherlands

Charley Toorop was not primarily interested in illustrating the dance or the movements involved in dancing. First and foremost, her interest lies, as in her self-portraits, in the portrayal of human emotions. Her paintings are realistic, characterized by heavily accentuated lines, severe shapes and intense application of contrasting colours. In Dancing Peasants, Toorop paints a close-up ‘snapshot’ of a group of peasants mingling at a party in an extremely crowded location. Bright and less vibrant light falls over the men’s faces, resulting in hard facial features. The eyes, the noses, the cheek bones, and even the teeth are highlighted by the direct interaction of light and shade. The blue-eyed man, featured dead-centre, looks directly outwards. He, as his girlfriend, is more pensive than his companions. Notable is that his partner’s face, despite having Toorop’s customary sharp edges, has a softer countenance. And how do they dance? The three dancing couples, including the cropped couple in the lower left corner, embrace each other closely and probably do little more than gently shuffle, limited by the sparse space available to them.

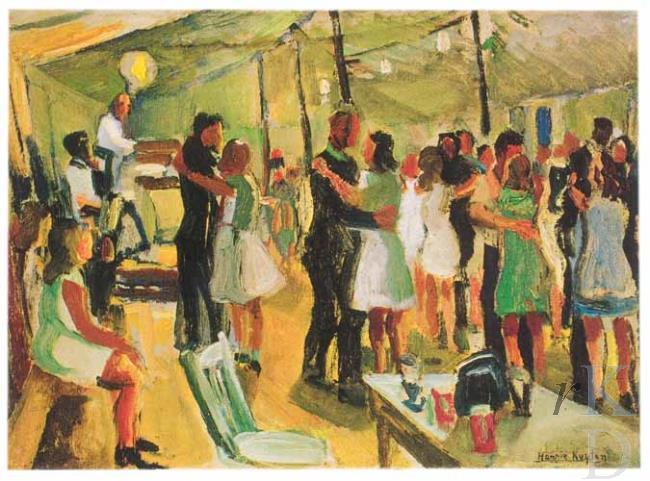

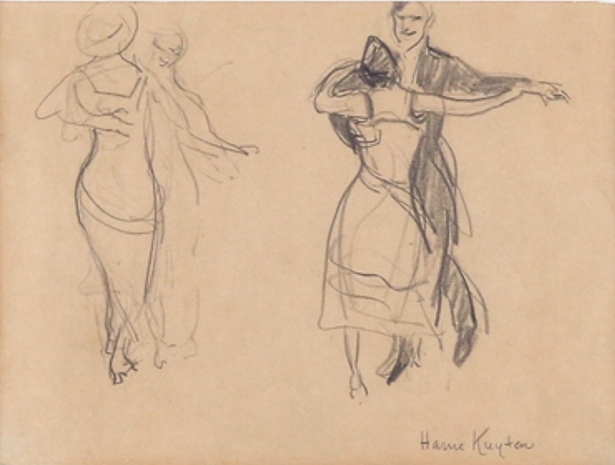

Within a large oeuvre consisting of street scenes, beach scenes, portraits, and animals, the prolific artist Harrie Kuyten (1883-1952), a member of the Bergen School, painted, as far as I could discover, two dance-related works. One work is lost; I only came across a poor black and white copy. The other, a colourful painting of a similar scene, is as lighthearted as his playful, fun-loving seaside paintings. The action takes place on a warm sunny day, in the village Groet not far from Bergen and records a pleasant scene of people enjoying themselves. Kuyten was definitely interested in capturing dancers in motion; a small sketch of two dancing couples illustrates his successful endeavour to achieve movement on a two dimensional plane.

Renée Smithuis Kunsthandel Heiloo/Castricum – RDK

and right – a sketch of two dancing couples, 16 x 21,5 cm

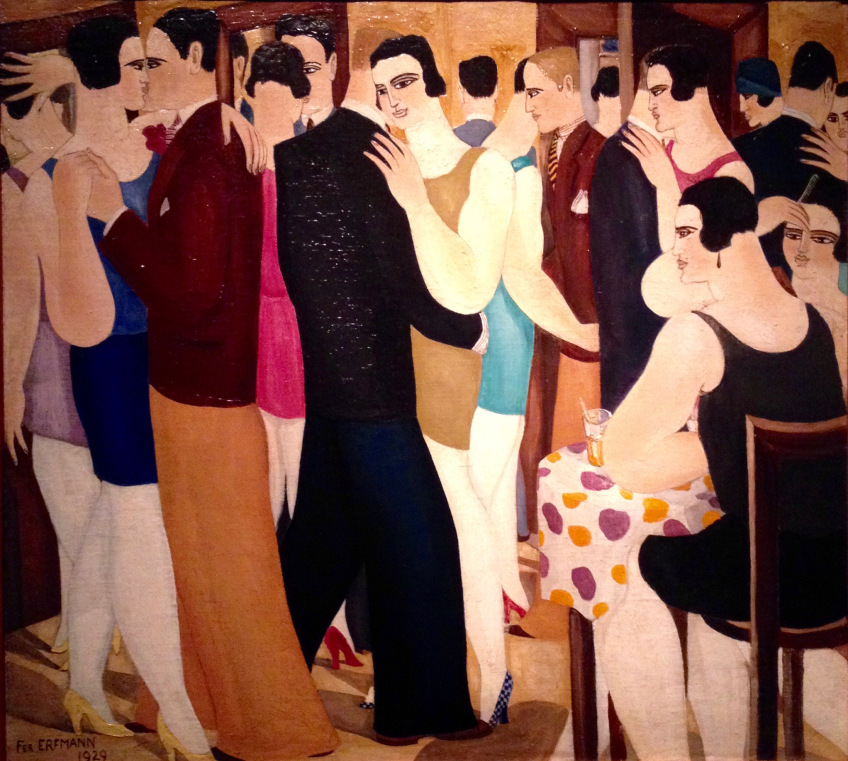

The independent artist Ferdinand Erfmann (1901-1968) was, besides a painter, an acrobat, and an actor. His favourite subjects included acrobats, dancers, performers, cyclists, beach goers, and scenes from daily life. He painted figurative work, but none of his figures is in any way realistic; they are always static, a motionless physique formed by a vivid plane of colour lacking any inkling of texture. The women often have exaggerated upper arms, have exceptionally broad hips, and are frequently disproportionately shaped. The figures shown in Dancing, by comparison, are elongated with just a suggestion of refinement.

This dance evening takes place in a smart establishment, likely a nightclub. The partygoers are very fashionable, the women’s hair cropped in the trendy ‘la garçonne‘ style. Erfmann has not painted any of the popular 1920s dances; Charleston, Black Bottom, Shimmy, or Quickstep. Besides, the women all wear those strapless shoes, making such fast-moving dances impracticable to perform. Rather Erfmann, on this crowded dance floor, has illustrated a slow dance that requires little displacement or energetic movement. These couples dance intimately, their bodies touch firmly, with partners resting their head on the each other’s shoulders. The artist commands our attention to the facial features of the various figures. Though none of the figures are lifelike, they are expressive. The centre woman, who catches all the light, seems to have a story to tell, like the robust woman sitting disheartened at the table. The tablecloth, just a point of interest, is the only multi-coloured object in the painting.** Nearly forty years after Dancing Erfmann painted a comparable painting; Dancing Couples is housed at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam.

As the 20th century progressed, art in the Low Countries pursued new avenues. Paintings of social dance events became fewer and far between. Artists favoured Spanish dancers, exotic dancers, revue dancers and illustrating ballerinas on and offstage. Ballroom dancers, however, especially in spectacular dances like the tango, remained popular, and artists of De Stijl ventured into abstraction presenting an innovative concept of dance and dancers. Sculpture, photography, technology embraced the dance; all topics for further posts.

* A similar painting, titled Kermis in de Rustende Jager te Bergen, is housed in the Singer Museum in Laren.

** I am disregarding the striped tie and black and white shoe