There are a few points we should clarify before looking at the work of Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema. Lourens Tadema (1836-1912) as he was originally named was born in a small town in Friesland, a province in the North of the Netherlands. Tadema primarily trained in Belgium, then moved to London in 1870, to reside there for the remainder of his life. He achieved his greatest fame in England; in fact, he was a Victorian superstar. A brilliant artist, but also a shrewd businessman Tadema added Alma, a name belonging to his godfather, to his own name so that his name would appear under the letter A in exhibition catalogues instead of under T.

Lawrence Alma-Tadema dubbed ‘the archaeologist of artists’, was not specifically interested in dance; he was interested in all aspects of the ancient world and that included theatre, music, and dance. His fascination with the ancient world was awakened during a trip to Italy in 1863. Thenceforth he collected postcards, books, artefacts, prints about Egypt, Greece, and Rome and frequently visited museums to study and sketch artworks. His personal library counted more than 3,000 titles devoted, for the most part, to classical antiquity. Alma-Tadema strove to paint Egyptian, but more especially Greek and Roman subjects in an innovative manner uniting the splendour of the ancient world with the everyday life of Victorian society.

( the museum offers the following valuable information – ‘An ancient Roman family returns home to a warm welcome. The figures represent Alma-Tadema’s own family: the father is the artist; the girl below, his daughter Laurense. The central group comprises his younger daughter, Anna, embracing her step-mother, Laura.’)

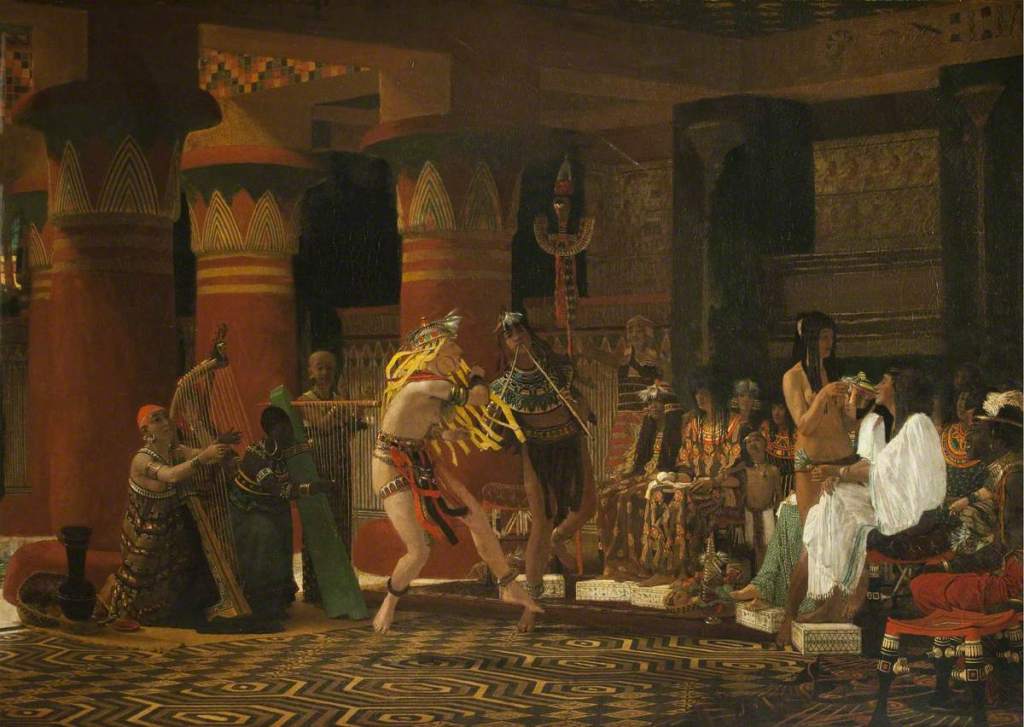

Alma-Tadema’s first major Egyptian painting, Pastimes in Ancient Egypt, 3,000 Years Ago, represents dancers and musicians performing in honour of a Nubian ambassador. Alma-Tadema researched this work, as all others, meticulously. All the items shown in this painting, whether chairs, stools, musical instruments, ornaments, or wall-paintings, are derived from the most distinguished archaeological books or from displays at The British Museum, The Louvre, or the National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden. Pastimes is influenced by a wall-painting, discovered in the tomb of Nebamun, which is still on display at The British Museum. Alma-Tadema, inspired by this banquet scene, created a finely rendered social scene copying original artworks and artefacts. The banquet’s inspiration is twofold; the main scene shows, dancers, musicians, a semi-naked servant girl offering a beverage to the ambassador and elaborately bejewelled guests, as depicted in the wall-painting, and on the wall above the attendant, a near copy of the original tomb-painting.

Images of Egyptian dancers, familiar from wall-paintings, are two-dimensional line drawings. As a general rule, the torso faces the audience, the head is shown in profile, and the figures are flat. Even the most energetic dancers, despite their exciting acrobatic movements, appear posed, static, and lifeless. The same cannot be said for Alma-Tadema’s dancers. The two dancers, one playing a double flute (diaulos), are lively individuals; enthusiastic Egyptian entertainers. The diaulos player, wearing an elaborately decorated wide neck collar and impressive headgear, is shown maneuvering on one leg. The slight curve of the body suggests possible switches from one leg to the other; not the easiest of moves whilst playing a double flute. The other dancer, also fastidiously attired including ornate armlets and multiple anklets, is actually hovering in mid-air. Both feet have left the floor, as if the dancer is pouncing or ricocheting off the ground. The same dancer is flooded in a ray of sunlight, standing under a ‘theatrical spotlight’. Alma-Tadema intentionally highlights the dancer. He not only underscores the jump, but wittingly rotates the dancer’s body, and in doing so triggers both ambiguity and sensuality. The dancer’s legs and arms are muscular and well-rounded, the face could be masculine or feminine, but the rotated torso reveals the dancer’s bare breasts. It was not uncommon for Alma-Tadema to include a touch of exoticism, a suggestion of sensuality, to gratify his clientele. This dancer is the most vibrant force, an alluring factor, in an otherwise reposeful painting. The dancers must have pleased Alma-Tadema; in 1868 a watercolour appeared, reproducing only the two dancers, not in an Egyptian architectural setting but in the open-air.

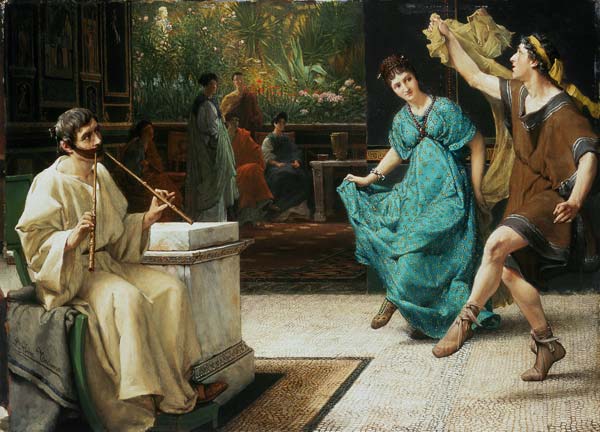

A Dance in Old Rome is a small painting, representative of Alma-Tadema’s ideas. It depicts a simple indoor scene showing a couple dancing accompanied by a musician playing a diaulos. At the back other Romans watch the dancing. The dancers, though entirely in the foreground, are placed off centre; a section of the scarf, that the man is holding, has been cropped. This all takes place in a comfortable Roman setting with a wonderful garden full of plants and flowers, seen through a spacious opening. These Romans are pictured as ordinary people. They are not depicted as heroic historical representations, as in the Davidian School, but people performing day to day actions in a historical setting. Alma-Tadema characteristically depicted Greek and Roman citizens as ordinary people, inviting Victorians to draw parallels between the lifestyles of the ancient world and that of their own society.

A Dance in Old Rome shows the dancing couple is performing a simple skipping or hopping step, the women inclining slightly forward towards her partner. She, either to appear especially graceful or to avoid tripping, holds her long skirt daintily to the side. The couple’s movements appear very natural, not unlike the steps performed in a 19th-century ballroom or for that matter in a children’s dancing class. Their attire, painted with Alma-Tadema’s exquisite eye for detail, is inspired by antiquity. Especially noteworthy is that the man carries a long floating scarf, inspired no doubt by the sweeping scarves that appear in various Roman wall paintings. A few years later (1873) Alma-Tadema revisited this dancing couple in his designs for the underside of a keyboard cover for his piano. Where the dancers in the painting are reserved, the dancers in the sketch are lighter and freer. The steps are just as basic, but they dance with less reserve, thrust their legs higher and use their torsos actively. To add to the impression of joviality, both dancers have long scarves flying behind them. In the final stage, the piano, the dancers have their own panel, are farther apart and dance, now carrying even longer scarves, with great abandon.

Above – Lawrence Alma-Tadema – study for Merry Music – 1873 – underside of keyboard cover Below – John Broadwood & Sons pianoforte – designed and decorated by Alma-Tadema. The piano remained in the possession of Alma-Tadema until his death in 1912.

The Pyrrhic Dance caused a sensation when exhibited at the Royal Academy of Arts (London) in 1869. Alma-Tadema was inspired by vase-pictures and reliefs of heavily armed Greek warriors, wearing bronze helmets, carrying shields, and javelins. According to written sources from antiquity, the pyrrhic dance was initially an armed dance. Later it was performed by warriors at funerals, developing into a useful training for military exercises. In Athens during the Panathenaea, there were even pyrrhic dance competitions. Plato describes ‘the bending aside, ducking, leaping, and crouching’,* that took place during this mimetic combat. In Alma-Tadema’s painting, pyrrhic dancers perform for all-male guests at a Greek symposium. Elderly and young men watch a group of performing warriors with varying degrees of interest. The close proximity of the mature bearded men and the clean-shaven effeminate youths, and the possible allusions thereof, invited controversy. John Ruskin (1819-1900), English writer, philosopher, and art critic, was more concerned with Alma-Tadema’s representation of the classical world writing “the most dastardly of all these representations of classic life, was the little picture called the Pyrrhic Dance, of which the general effect was exactly like a microscopic view of a small detachment of black-beetles in search of a dead rat.”

Ruskin’s comments are, luckily, but one opinion. I, for one, am fascinated by the striking contrast between the mature men and youths reposing under the Doric colonnade and the bold activity of the pyrrhic dancers. The spectators, all strongly individual figures, fill the entire background. I presume that the more significant Athenians are seated, and those of lesser importance are jammed against the back wall or crammed behind the columns. The elderly bearded man, lounging next to the column, observes the dance with interest; this is more than can be said for his bored, nevertheless good-looking companion. The fair-haired youth looking over his shoulder, in contrast, is totally spellbound. He, like the last dancing warrior, has been cropped. The leading warrior is situated firmly in the centre; Alma-Tadema offers a detailed depiction of this mighty champion. The shield, his attire, his bearing, his powerful legs, and his sunken pose, all commands our attention. He leads a troupe of warriors. These strapping men lean forward in unison, javelin in hand and shield held resolutely above the head performing a mock battle. I can merely guess how many warriors are performing; the figures overlap though the cropping could imply that the line is much longer. The man looking around the column certainly gives that impression.

I have no idea in how far this painting, which Ruskin denounces, is a representation of life in classical times. I, however, find The Pyrrhic Dance with the staunch warriors a stunning painting. The dancer’s forceful alignment together unquestionable sensation of forward locomotion is convincingly dynamic. Likewise the serene colours, the spatial design, the overpowering Doric columns juxtaposed with congested crowds leave little to be desired.

Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, celebrity, socialite, designer, man of the town, and artist, combined the deep-rooted Dutch traditions of genre painting with his own innovative way of interrelating the ancient world with the then modern world. He became the most coveted artist of the British society.

* The Dance in Ancient Greece – Lillian B. Lawler – page 108 – Adam & Charles Black, London 1964