A new generation of artists emerged in Amsterdam in the early 1880s. These young artists, influenced by the writers Emile Zola and Baudelaire, portrayed the day to day life of ordinary people. Their search for realism drew them to taverns, dance halls, and cafés, places that working class frequented. Isaac Israels, together with his friend, the writer Frans Erens habitually meandered through the streets of nighttime Amsterdam, drifting from one café to the next, visiting legal haunts and more often than not hanging out in illicit establishments. The two Bohemians drank, danced, flirted, and played the field enjoying the entertainment that inspired them to depict the sultry nightlife in image and prose.

The shabby dance hall in Dancing women on the Zeedijk is not particularly busy; a solitary accordionist, two dancing couples and some disheartened women. Why is the dance floor so empty? Where are the other pleasure-seekers? Did Israels arrive early hoping to see just a few whirling girls? It is evident that dancing figures intrigued him. Israels repeatedly sketched gyrating dancers. These robust working girls dance arm in arm; their wide skirts fly effortlessly with each successive turn. Significant is that the faces of all the people present, even though only marginally sketched, are meaningful. The two dancing women are cheerful enough, but those women sitting at the side look thoroughly bored. And the accordionist, a somewhat older man, shows little enthusiasm. All the figures are outlined by a thin black line; quickly sketched on the spur of the moment. The interior, the floor and the wooden beamed ceiling are rendered in more detail. And what are those two yellow markings? There is a bright spot among the beams and a dimmer yellowish light above the accordionist. It is 1893, Israels had encountered electric light.

Isaac Israels – Dance hall on the Zeedijk – 1893-5 – Erens Archief, Nijmegen – This colour image has been cropped. The original pastel, which I could not find in colour, is rectangular in shape showing an additional two women sitting on the bench next to the men (see the second image in the side-show).

In Dance hall on the Zeedijk, another impression of nocturnal Amsterdam, the dancing couple is, once again, the focus of attention. The women hold each other firmly, spinning round energetically; their skirts whirl out into a wide semi-circle. On a hard bench, just behind them, a group of not so young men drink, lounge, and stare. These men, sailors, labourers, boozers, together with a man wearing a high hat, are content to just sit and watch the whirling women. They make no effort to get up or to dance. As in the previous image, Israels has sketched the figures in black, later adding some understated areas of blue and red. The overall image is dim, even gloomy. The men are barely distinguishable; except that a light reflects on the insignia of the centre man’s cap. Just above him shines that most modern of inventions; a clearly visible electric light bulb. Israels was fascinated by the prospects and enterprise of modernity. Electric light, the illumination of a city, whether in shop windows, street scenes, cafés or theatres, became an integral part of his art.

Isaac Israels – Dancing at a fair in the Jordaan – c.1894 private collection – RKD

The bandstand is an oasis of light illuminating the entire square; in the background, Israels has sketched the luminous contours of typical Dutch houses. The district known as Jordaan is situated in the centre of Amsterdam and known, even today, for its warm-heartedness. In Israel’s time the Jordaan was a charismatic working class district, where festivities were celebrated with unrivalled vigour. These two women must dance especially well; spectators have moved to the side, giving them ample space to swing round in circles. Their footwork and their wide swivelling skirts, reveal how quickly they are rotating.

With little more than a few quick brushstrokes Israels illustrates the spontaneity of these dancing maids, factory workers, seamstresses and shop assistants; girls and young women dancing to escape, momentarily, from the drudgery of their hardworking daily existence. In these and dozens of other rapid sketches, Israels captures their abandon as they sway, turn and stomp to the incessant rhythm of the music. Writer Frans Erens who together with Israels was a participant at umpteen dance affairs, auspiciously describes the motions of the dancers in his prose poem ‘Zeedijk’;

‘the skirts whirled, whirled; the heads twirled, twirled; the feet stomped stomped; the knees buckled, buckled; the bodies shook, shook’.*

Left: Dancing Women – oil on canvas – 97.5 x 74.5 – c.1892-1897 – Kunsthandel Simonis & Buunk & Right: In the Dance Hall – oil on canvas – 76 x 100 cm – 1893 – Kröller Müller Museum (click on image to expand)

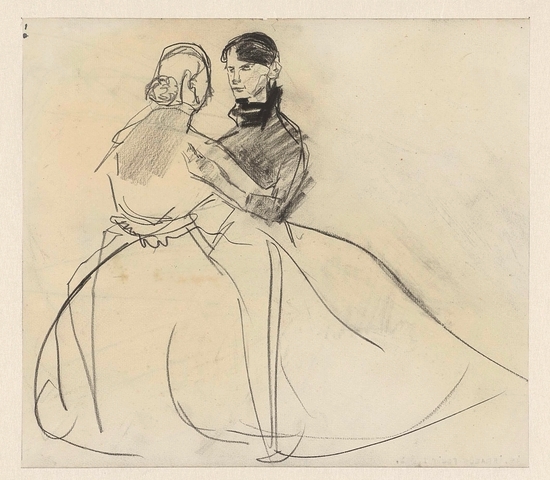

Where in all the previously discussed images Israels regarded the dance and dancers as a whole, in these two oil paintings he takes a closer look at the women themselves. It is obvious that they are dancing, and equally obvious that these are robust, working women. Dancing Women, shows the figures in a three quarter portrait, conveying the interaction between the two women. The composition revisits earlier studies where the dancers face each other, hold each other by the shoulder and wear the customary spacious skirts. I am not sure, but perhaps these hardy, not especially pretty, women are still wearing their work aprons. It may be worth mentioning at this stage that it was not unusual for two women to dance together. Male partners were not always available and wasting a dance, like the downcast woman sitting on the bench, was not exactly what you expected to do on your free Saturday evening.

The colour red dominates the near claustrophobic painting In the Dance Hall. The two dancing women, now shown from the waist up, command the central area. Unlike the sturdy homely figures in Dancing Women, these women have made a real effort, even wearing earrings and adorning their hair with a chain ornament of white stones. But, despite their fashionable appearance, neither of the women looks especially cheerful. One woman looks downwards; the other looks slightly to the side. Why the woeful expression?

The dance hall is filled to the brim with people dancing to the rhythm of the trumpet player. This apparently insignificant fellow is propped in the upper right hand corner. The entire image is dramatically confined; every inch of this canvas is cramped with dancing couples. There is little space to whirl or twirl. These dancers are restricted to shuffling and stomping on the spot. The man on the right, his head reaching just above the centre woman’s shoulder, is unmistakably expressive. The dark setting accentuates and intensifies his rugged face, his rough features, and probing eyes. This stifling painting is so much more than a fleeting impression of an entertaining dance hall. Israels explores intense personal emotions. Israels, although recognized as a leading Dutch impressionist, demonstrates, in this work, his uncanny affinity with expressionism.

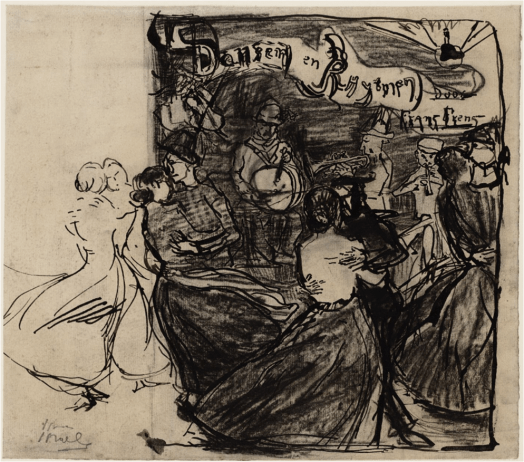

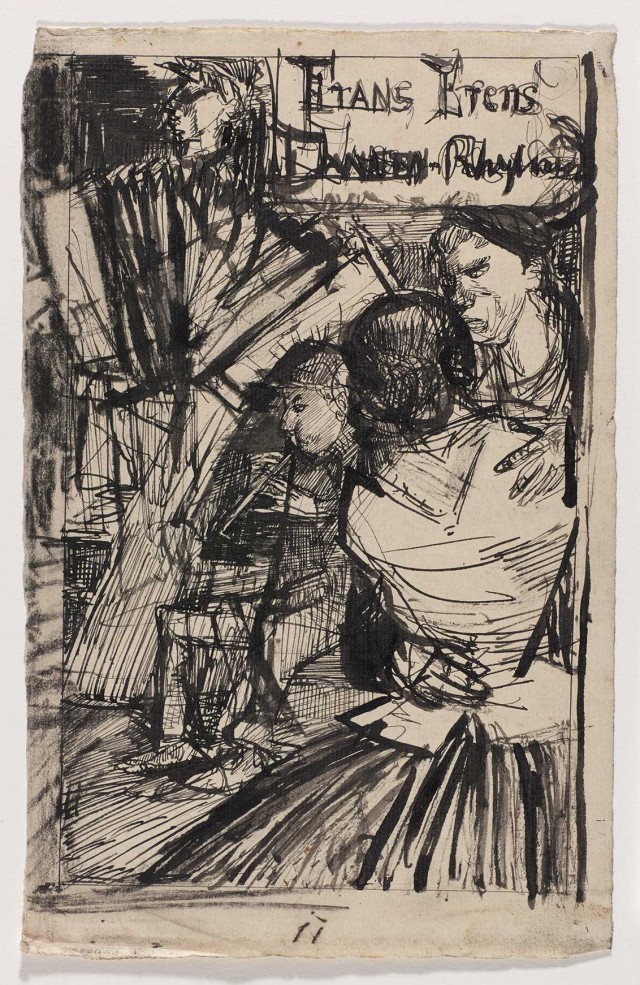

- Cover design – Dansen en Rhytmen – Isaac Israels – Beeldbank – this image, according to Frans Erens, was actually drawn when he and Israels visited a dance hall on the Zeedijk

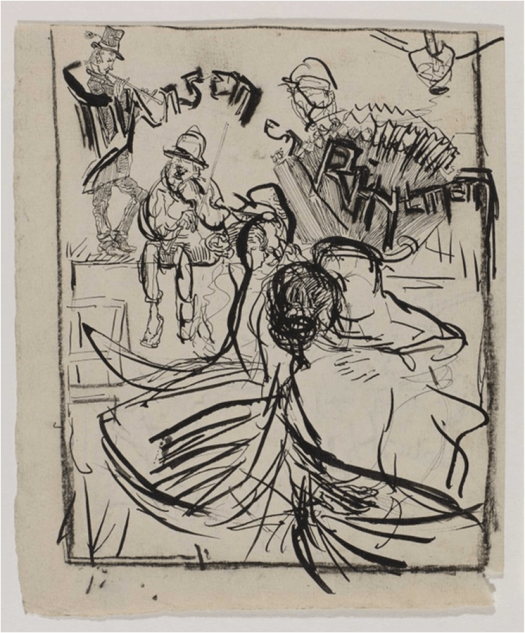

- Cover design – Dansen en Rhytmen – Isaac Israels -Kunstmuseum Den Haag

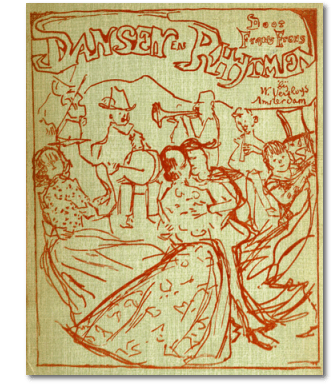

- Cover – Dansen en Rhytmen – Isaac Israels – 1893

- Cover design – Dansen en Rhytmen – Isaac Israels – Kunstmuseum The Hague

Dansen en Rhytmen (Dances and Rhythms) is a bundle of prose poems by Frans Erens, Israels friend, about life in Amsterdam. Erens like Israels drew inspiration from the commonplace, the working class, the poor neighbourhoods and as we have already seen, the cafés and dance halls. Israels devised a number of designs for the cover of Eren’s work. The sketches are delightful, playful and above all spontaneous. The swirling wide shirts, the revolving dancers, the musicians that play a variety of instruments, all create the carefree sphere of an animated dance hall. Each of the above designs is seemingly nonchalant; just a few charcoal lines and some impetuous brush strokes.

Israels pursued spontaneity. His dance images have all the hallmarks of a photograph. Not a posed photograph, but a snapshot; a spontaneous fragment of time. He achieved this effect by sketching quickly, slapping paint rapidly on the canvas, rarely altering anything while working on a particular canvas, and by following the advice he gave to art students, “Never spend too long on a piece, never work at it for too long at a time…”.**

- * with thanks to Breitner vs Israels – Vrienden en rivalen page 217 – Frouke van Dijke – Kunstmuseum The Hague, 2020

- ** Isaac Israels page 13 – Anna Wagner – Art and architecture in the Netherlands, 1969