1906. Jan Sluijters, recipient of the prestigious Prix de Rome, travelled to Spain to study the old masters. Apart from working in the Prado, Sluijters became fascinated by the Spanish dance, visiting the local theatres and dance venues. There, Sluijters drew sketches of these Spanish beauties and on his return to the Netherlands completed The Spanish Dancer, a painting that would astound, shock, or enrapture, depending on the audience.

The youthful Sluijters, who had received the Prix de Rome, for his great proficiency of academic art, dumbfounded both teachers and mentors with his dynamic swing to modernity. Sluijters visited Paris, in 1905 and again in 1906. Fauvism fired his creative spirit.

No wonder that the Spanish Dancer was considered to be a betrayal of academic art principles. Sluitjers’ carefully rendered lines, his ‘correct ‘use of colour and his balanced compositions, all made way for the innovative, inflamed by the French avant-garde; Matisse, Derain, and of course fellow Dutchmen, Kees van Dongen.

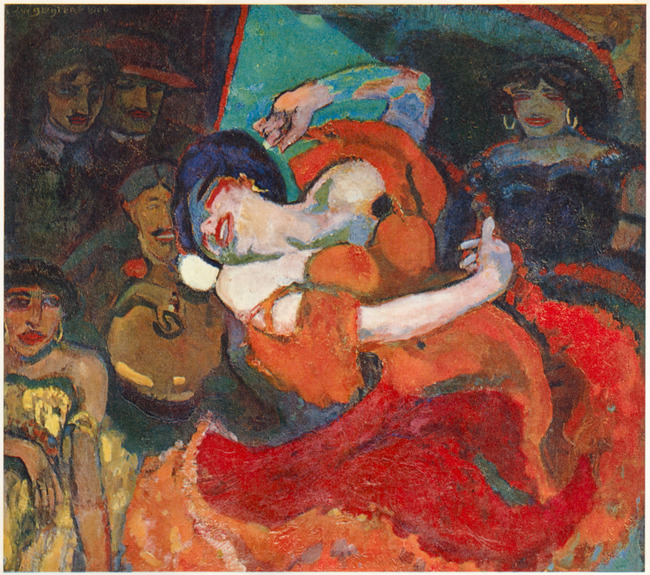

The swirling dancer immediately draws all the attention. The abundant red and orange hues bounce off the canvas. Sluijters’ contrasts colours in a non-traditional way, juxtaposing red with green like Van Dongen. By the same token the dancer’s face and skin are smudged with blue, green, and a reddish tint and her hair has an intense blue glow; a coloration, remember this is Amsterdam 1906, that was deemed totally unacceptable. Sluijers’ marked distinction between light and dark caused further misunderstanding. The dancer’s face together with her flamboyant dress is swamped in glaring light, whilst in the background, musicians and spectators gradually ebb away. Her protruding breasts are especially accentuated by bright spotlights. Just as startling, from a painterly point of view, is that Sluijters’ has outlined his figures in black, paints with irregular, somewhat rough strokes and applies the paint unevenly. The Spanish Dancer greatly displeased members of the Prix de Rome committee, but was admired by others; various critics remarking on the artist’s bold use of colour and his daring expressiveness.

Living in the Netherlands, I have had the opportunity of seeing the Spanish Dancer, a number of times. Each and every time, the painting overwhelms me. Sluijters truly understands the nature of the dancer’s movement. His dancer demonstrates a strong forward thrust of the pelvis that induces a rotation of the torso which, in turn, throws the arms into a rounded pose. The dancer visibly enjoys the flow of the movement, inclining her head resolutely onto her shoulder. This is a not static pose, but a fleeting moment in an exhilarating Spanish dance. As an onlooker, you can almost feel the spiral sensation.

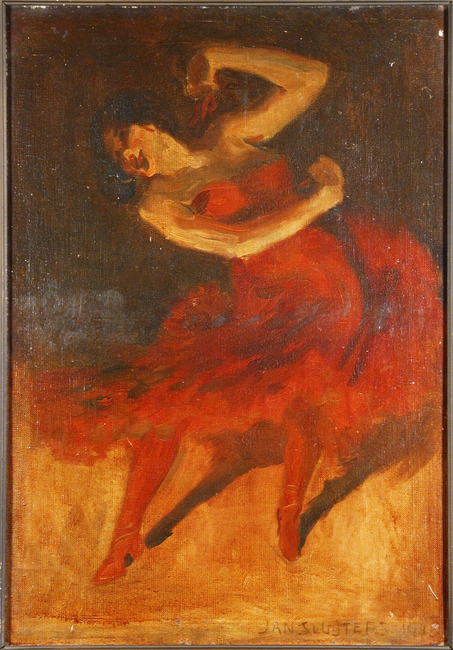

left – Spanish Dancer c.1905 – study Madrid – RKD

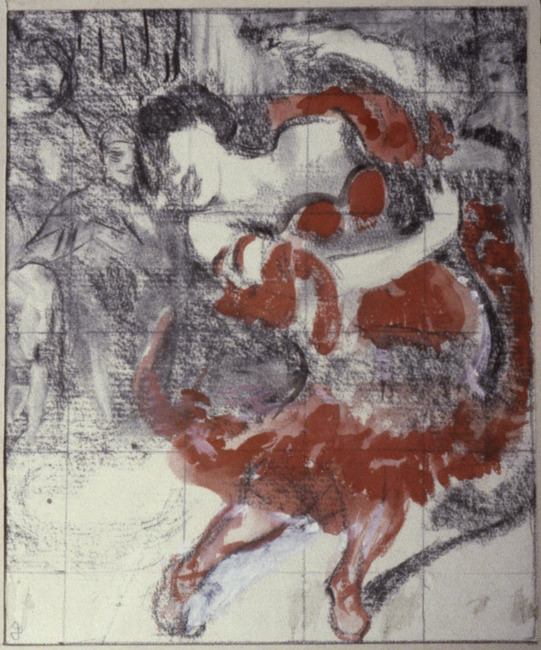

right – Spanish Dancer – study – RKD – note the grid

(click on image to expand)

The Spanish Dancer may appear to be a spontaneous work, but, looks deceive. Jan Sluijters being the meticulous artist he was, made a number of sketches and preliminary studies during his stay in Madrid. In all his dance works, Sluijters demonstrates an uncanny ability to translate three-dimensional movement onto a two-dimensional plane. The dynamic rotation, so successfully represented in the Spanish Dancer, has been fastidiously perfected in the process of various studies. An early study (above left) shows a full-length dancer powerfully swirling; Sluijters experimenting with the movement possibilities of the dancer. The right image reveals more about the artist’s working process; he designed his compositions with the aid of a grid. This study is very similar to the final painting, except that the dancer is shown full length. It is clear that from an early stage Sluijters had foreseen a group of people, less prominent figures, in the background. In the final painting, he discarded the dancer’s feet and legs, cropped a large section of the skirt, focusing exclusively on the fiery dancer.

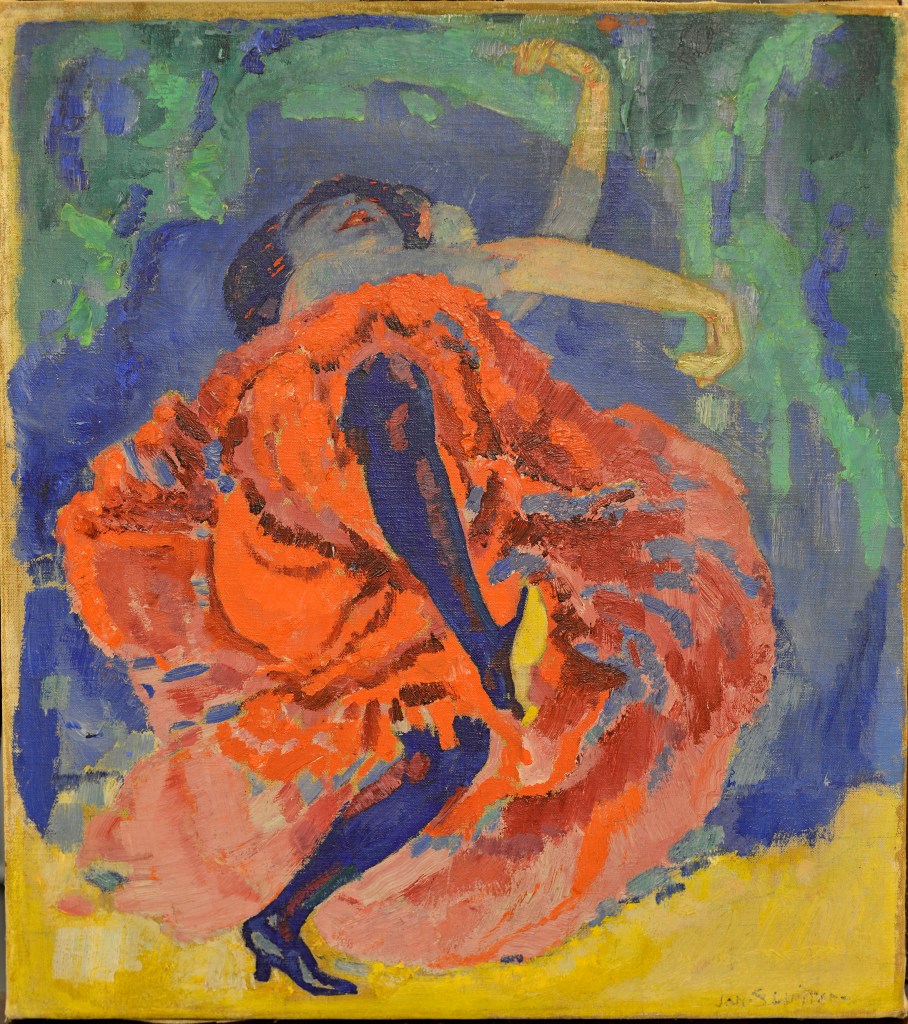

Amid a massive red skirt, a ravishing blue leg is thrust towards the onlooker. The bright yellow sole of her shoe is visible to all. Shades of red, yellow, blue, and green, applied in large splashes, feature in this extraordinary painting that Sluijters painted in 1907. Sluijters inspired by the Fauvist painters, used a daring colour palette. There is no escaping the stupendous impact of the central red area. This flurry of reddish tones, the dancer’s skirt and bloomers, forms an enormous circle that covers two-thirds of the canvas. Contrary to his academic training, Sluijters places the main figure in a non-realistic background. A yellow tone, the same as the shoe sole, claims the lower section while the area behind the dancer is blue adorned with irregular strokes of green. This painting, made in what is sometimes referred to as the artist’s ‘Wild Years’ was, in the eyes of conservative Dutch art, too bold, too ‘untidy’, and displeasing.

This Spanish dancer, flaunting her leg kicks, is a stunning mover. Sluijters innately understands the mechanics of body awareness as well as the dynamics of her spirited movement. He has captured her energy, her vivacity, and her passion in a most convincing way. Although not a fervent dancer, as his contemporaries, Van Dongen and Mondian, Jan Sluijters loved to watch dance and commanded an instinctive sense of movement.

Jan Sluijters, as his peer, Kees van Dongen, were highly interested in movement; both painted dancers, acrobats, and circus artists, preferably those performing in dance halls, theatres and circuses where electric lighting had been installed. The effect of electric lighting is paramount in the Spanish Dancer. You will have noticed that the entire skirt, bloomers, and legs are fully illuminated. Contrarily, the dancer’s face and part of her arm retreat into shadow, colouring an unnatural, subdued, blueish shade.

Electric light is a vital component in Sluijters’ masterpiece Bal Tabarin, a large painting featuring couples dancing randomly under an expanse of radiant light. This painting was revolutionary, controversial and invited endless consternation. As a result, Sluijters lost the Prix de Rome. Jan Sluijters, however, in his youthful years, remained a rebel; Paris had awakened his ‘wild spirit’.